Views: 1322

This text aims to present the Lithuanian legislative framework concerning linguistic rights and minority protection. For the preface, a general overview of minorities in Lithuania is going to be done. It is going to be followed by the presentation of the legal framework of the country. It will be confronted with the facts concerning the situation of minority groups in Lithuania especially two of the biggest of them: The Poles and the Russians.

Minorities and minority rights

Minority rights, as applying to ethnic, religious, or linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples, are an integral part of international human rights law. They are a legal framework designed to ensure that a specific group that is in a vulnerable, disadvantaged, or marginalized position in society, can achieve equality and is protected from persecution.[1]

The term “minority rights” embodies two separate concepts:

- Standard individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic, or sexual minorities.

- Collective rights accorded to minority groups.

Collective rights include not only the fundamental right to official recognition and the right to existence and identity but other fundamental rights as a consequence of the recognition. These rights include the right to use one’s language in the public sphere, the right to education in one’s native language, the right to establish separate organizations including political parties, the right to maintain contacts with the kin-state or persons and institutions who share the same culture, and the right to exchange information and mass media in one’s native language. In terms of international law, collective rights mean that a group is subject to the right, and hence a minority as a whole is entitled to rights, not just their single members. The group rights are more than the simple sum-up of the individuals. Minority protection, therefore, requires a combination of collective and group rights.[2]

The term may also apply simply to the individual rights of anyone who is not part of a majority decision. Civil rights movements often seek to ensure that individual rights are not denied based on membership in a minority group. Minority rights cover protection of existence, protection from discrimination and persecution, protection and promotion of identity, and participation in political life.

The recognition and protection of ethnic groups and national minorities is fundamentally an issue of state-level politics, but at the same time minority question has an international character. These problems deal with bilateral agreements containing also minority provisions and international conventions. The main international organizations, which are interested in minority matters are the United Nations (in global terms), the OSCE (in continental term), or the European Union (in regional term).[3]

Nevertheless, the term “national minority” is still ambiguously defined in specialized literature as well as in the political debate. Generally speaking, “minority” means a community compactly or dispersedly settled on the territory of a state, which is smaller in number than the rest of the population of a state. Members of that community can be citizens of that state, but have ethnic, linguistic, or cultural features different from those of the rest of the population and are guided by the will to safeguard these features.[4]

A minority is designated as national (“national minority”) if it shares its cultural identity (culture, language, tradition) with a larger community that forms a national majority elsewhere. In contrast to this, the term “ethnic minority” refers to persons belonging to those ethnic communities which do not make up the majority of the population in any state and also do not form their nation-state anywhere (“stateless culture”). Given the difficulties of precisely carrying over the existing great variety of terms into the most important European languages, the Council of Europe (not the European Council), when editing the “Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities” has chosen to simplify the terminology and decided to use the expression “national minority” in a representative manner.[5]

Minorities in Lithuania

In Lithuania, there are mainly “national” minority groups. Instead of living in the country of their nation, here live the Russians, Poles, Belarussians, Ukrainians, and some, but not many Latvians. Nowadays without strong representation are the Jews and Germans. The pure “ethnic” or “stateless” minority form the Roma (Gypsies), Tatars, and Karaims (Karaites), which do not have their national state. Nevertheless, their number is not the sign but the historical role of Tatars and Karaims in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was very important.[6]

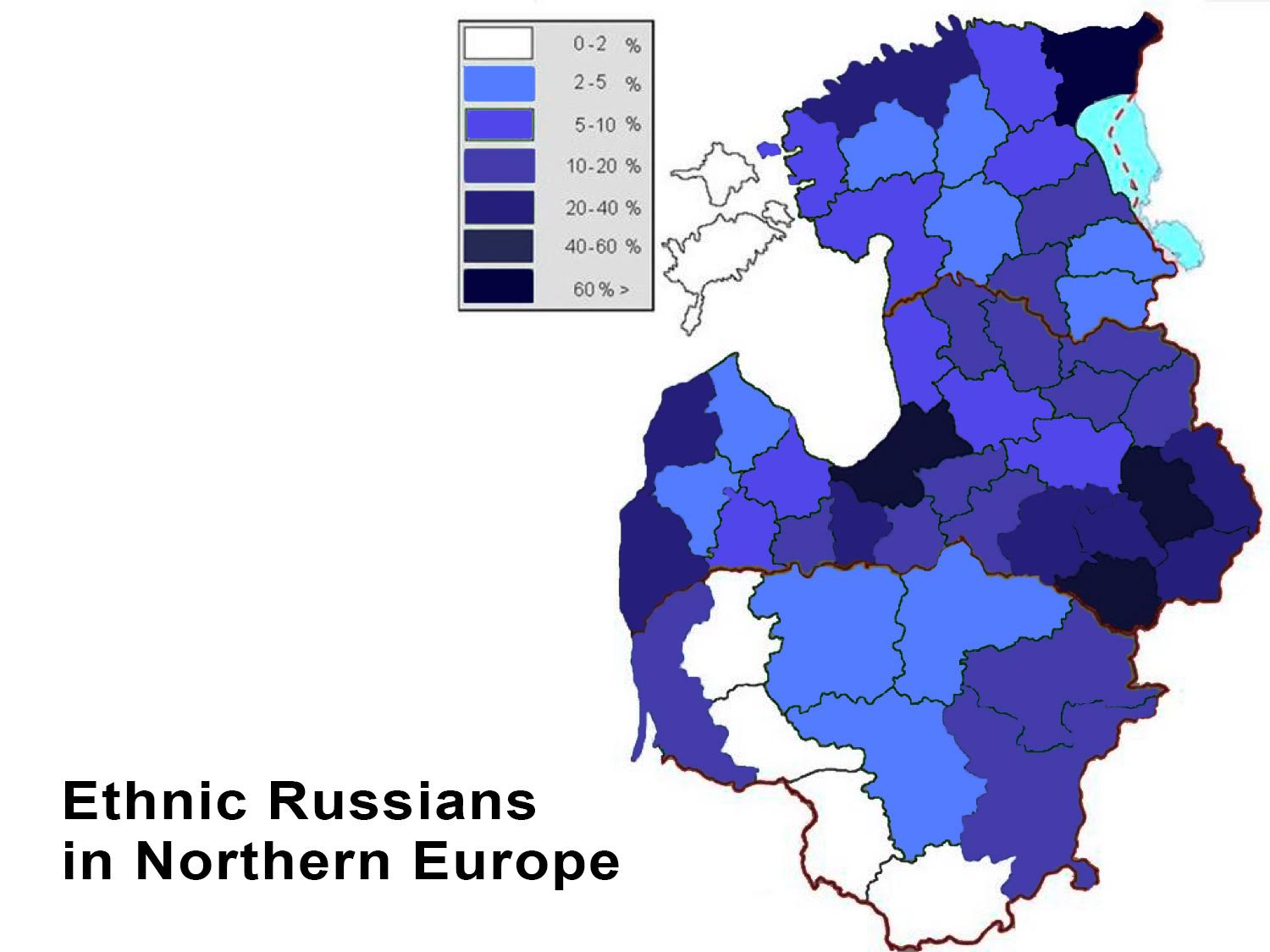

The most numerous minorities nowadays are the Poles, Russians, and Belarussians. Their presence in Lithuania is a consequence of the turbulent and complex history of the country.[7] Because of historical changes, changes in the population through the years, decades, and centuries can be observed. For instance, the number of ethnic Russians was bigger in the Soviet time compared to the post-Soviet era: in 1989, there were 344.500 Russian in Lithuania (9.4%) while in 2016 left 6.3%),[8] or according to the census data from 2001, there were 219.798 ethnic Russians in Lithuania while according to the last census done in 2011, there were 176.913 of them.[9]

Nearly all minorities in Lithuania decrease in their numbers compared to ethnic Lithuanians during the last 30 years mainly due to three crucial factors: emigration, assimilation, and negative birth-rate. In opposition to many (West) European countries, the post-Soviet Lithuania is becoming more homogenous instead of increasing the migrants’ population. The rate of migration into the country is not very high. Minorities here are groups, which live on this territory for decades and centuries, and, therefore, many of them can be put into the category of “autochthonous” minorities. Like most national minorities in Europe, they live in their traditional homeland and due to historic evolution found them included in a state with a major, or “titular”, nation.

As a matter of fact, at the beginning of 2008, citizens of the Republic of Lithuania made 98.7% of the total country’s population what means, differently to the cases of Latvia and Estonia, almost all members of minority groups in Lithuania possess Lithuania’s citizenship and passport. In other words, that means, that people of ethnic-minority origins are Lithuanian citizens but not temporal “migrants”, “foreigners”, or “guest-workers” (“Gastarbeiter”). Most (93.4%) of the country’s residents were born in Lithuania[10]. The ethnic minorities are, in fact, autochthonous, as living in Lithuania for generations. During the restoration of independence in Lithuania after 1990, citizenship was granted to all individuals on its state territory irrespective of their national identity and without requiring them to learn Lithuanian (differently to the cases of Latvia and Estonia). The 1989 Citizenship Law offers the chance to become a citizen no matter when and how an individual came to Lithuania.

Today, the territory of the Republic of Lithuania covers 65.300 sq. km. (373 km. x 276 km.).

In 2018, there were officially some 2.900.000 inhabitants of whom 66.7% live in cities or towns. The biggest city is Vilnius (540.000) followed by Kaunas (360.000), and Klaipėda (157.000).

The ethnic breakdown of the country is as follows: Lithuanians (83.5%); Poles (6.7%); Russians (6.3%); Belarussians (1.2%); Ukrainians (0.6%), Jews (0.1%); and other very small ethnic minorities. The confessional composition of Lithuania is: Roman Catholics (79%); Christian Orthodox (4.1%); Old Believers (0.8%); Protestants (0.6%).[11]

According to the official state statistics, in 2001, there were 2.907.293 ethnic Lithuanians followed by 576.679 members of national, or ethnic minorities. However, according to the same source, ten years later (2011), there were 2.561.314 ethnic Lithuanians and 482.115 minorities’ members.[12]

The legal framework of minority policy

According to the official legal framework of the Republic of Lithuania, including the Constitution too, all citizens of the country, regardless of their national and other backgrounds, are equal before the law. The Lithuanian Constitution (1991) guarantees equal human rights and fundamental freedoms to all people.[13]

Today, there are 21 official and registered ethnic (minority) communities in Lithuania (Tautinės bendruomenės Lietuvoje) from Armenian one to Lebanese one. All minority questions are regulated via and by the Department for Ethnic Minorities – Government of the Republic of Lithuania (Tautinių mažumų departamentas prie Lietuvos Respublikos vyriausybės) in Vilnius. Several articles of the Constitution are touching the status of the minorities in Lithuania. For instance, Article 37 of the Constitution spells out that “Citizens who belong to ethnic communities shall have the right to foster their language, culture, and customs.”[14] Further, Article 45 acknowledges that „Ethnic communities of citizens shall independently administer the affairs of their ethnic culture, education, organizations, charity, and mutual assistance. The state shall support communities“. However, all representatives of the ethnic communities in Lithuania are not satisfied with the official name of the Department dealing with them as they do not want to be called „minority“ but rather „ethnic community“which is even more fitting to the text of the Constitution.

From the very political point of view, in the Appeal to National Minorities of Lithuania of March 12th, 1990, the Supreme Council-Restoration Parliament committed itself that all political and economical decisions of new and independent post-Soviet Lithuania will be enacted considering the interests of all national minorities living in Lithuania, not humiliating national dignity and rights. We have to keep in mind that on March 11th, 1990, the Supreme Council of Lithuania (today Seimas/Parliament) proclaimed the act „On the Restoration of the Independent State of Lithuania“ and, therefore, it was of extreme importance to attract Lithuania’s ethnic minorities (especially Russian) to support the independence. For that reason, the Appeal of March 12th, 1990 was very favorable for the minorities.[15]

What is very important, Lithuania since 1991 is a member of the United Nations Organization (UNO) and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and since 2004 a member of the European Union (EU). Because of this fact, the country is obliged to respect international conventions concerning human rights and minority rights. Lithuanian law has to be also adapted to the patterns of the EU’s law. Lithuania is, as well as, a signatory of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Finally, Lithuania ratified the most important documents of the Council of Europe in 2000. However, Lithuania has so far not signed the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages most probably to avoid possible regionalization of the country according to the language lines especially fearing Polish nationalism and separatism.[16] It seems that there are no such intentions at the moment. We have to keep in mind in this respect that in two Lithuania’s regions the Poles are composing the absolute majority of the population: in Šalčininkai – 77.8%, and in Vilnius 52.1. Besides, in the Trakai region there are 30.1% Poles and in Švenčionys 26%. The town of Eišiškės has 83% of Poles, the town of Šalčininkai 71% of Poles, or Baltoji Vokė 58% of Poles. In 1989, there were 257.994 Poles in Lithuania but in 2016 left 162.000 of them.[17]

Lithuania has concluded several bilateral treaties with neighboring countries containing provisions on minorities but it is important to note that the treaties do not contain provisions regarding the Roma (Gypsies) – typical for a dispersed minority without a kin state.[18] For example, the bilateral Polish-Lithuanian Declaration on Friendly Relations and Good Neighborhood Cooperation signed on January 13th, 1992, and the following Treaty on Friendly Relations and Good Neighborhood Cooperation, signed on April 26th, 1994, recognized the existence of the Polish minority in Lithuania and the Lithuanian minority in Poland. They also obliged both states to protect their rights on a mutual basis (including the right to education in the respective minority languages).[19]

When it comes to the Constitution, there are although some controversies. As Jan Sienkiewicz, an active member of the Polish community in Lithuania, points out, the preamble of the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania has the following wording: “Lithuanian nation (…) having preserved its spirit, native language, writing and customs (…)”[20]. In the opinion of Jan Sienkiewicz, because the terms “native language” and “writing” used here are clearly in the singular, that means that other ethnic groups in the country of Lithuania, using different languages, and having its customs, and literature have been placed outside the constitutionally meaning of the Lithuanian nation (Lietuvos Tauta).[21]

Language

Article 14 of the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania provides that the state language (the language in public use) shall be Lithuanian.[22]

Nevertheless, the Law on Ethnic Minorities stipulates that in the regions densely populated by the minorities, other than the Lithuanian language can be used in administration and different offices. The term “densely populated” is, however, vague since it is not defined in the law or by the state authorities what it means more precisely in the practice. The right to use the minority language in addition to the Lithuanian as the state language in offices in areas of compact minority settlement is granted by Article 4 of the Law on Ethnic Minorities. Article 5 of the same law provides that in these areas, signs may be designed both in Lithuanian and in the minority language.

Another important law concerning the language issue in Lithuania is the Law on the State Language. Article 1 of this law provides that “the Law shall not regulate unofficial communication of the population and the language of events of religious communities as well as persons belonging to ethnic communities” and that “other laws of the Republic of Lithuania and legal acts adopted by the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania shall guarantee the right of persons belonging to ethnic communities to foster their language, culture, and customs”.[23]

The Polish minority

The issue of using both languages in “densely populated” areas is most important for the Polish ethnic minority in Lithuania. The native speakers of Polish are found all over Lithuania, but over 90 per cent of the Polish minority in Lithuania live in and around the Lithuanian capital Vilnius (in Polish Wilno): in the municipalities of the Vilnius City, the Vilnius District, the Šalčininkai District, the Trakai District, and the Švenčionys District. How much the Vilnius District and Lithuania, in general, are important for Poland and Poles can be seen from the fact that in Vilnius, the Polish state TV company TVP has the office – TVP Wilno.[24]

As can be seen in the illustration on the map of the ethnic breakdown of Lithuania, the Poles in Lithuania are located mostly in a common area. In the Šalčininkai District and the Vilnius District, they are even clear arithmetic-statistical majority (79,5% of the population in the Šalčininkai District and 61,3% in the Vilnius District).[25]

However, their legal right to use the Polish names of streets was limited for a very long time. It was even the case that the Administrative Court of Lithuania issued a decree according to which, the placement of tables with names of the streets in Polish next to Lithuanian ones was contrary to law and, therefore, the Lithuanian authorities demanded to remove it and the persons, who were responsible for putting such tables, have been punished with a fine. However, the local Polish population refused to remove the tables. The local authorities of the Vilnius District intended to approach the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg with this case.

In essence, in the Lithuanian legal system exists a contradiction between the law on national language and the law on ethnic minorities, but in the practice, the law on national language is treated as a superior in the decision of the Administrative Court.[26]

The most vivid conflict in the relationship between the state authorities of Lithuania and Lithuania’s Polish minority as well as its Lithuanian counterpart in Poland is in regard to the spelling system to be used for both personal names and place-names in the respective minority languages and their local communities. According to the Lithuanian laws, personal names have to be written using the “Lithuanian alphabet”. It practically means that, for instance, Lithuania’s Poles, who are using the Latin alphabet as Lithuanians, still cannot use specific letters (graphemes) existing in the Polish alphabet but not in the Lithuanian one (for example, letter W/w). Earlier, moreover, even a Lithuanian nominative ending (suffix) had to be added to the personal names and family surnames, so the name could be inflected in Lithuanian. However, this practice of “Lithuanization” is no longer the case, but still, personal names in official documents are spelled differently from the original language: for example Lavrinovič but not Lawrinowicz.

Problems in this area might be solved by spelling names (and toponyms) in the languages using the Latin alphabet in their original form, i.e. in the form used by the local ethnic minority. Lithuania’s Poles are demanding exactly that from the Lithuanian authorities for over 15 years, but still without practical effect. It is worth pointing, that name of an international company can be written with letters that do not exist in the Lithuanian alphabet (for instance, WesternUnion). However, when it comes to the personal names and the family surnames, in 1999 the Constitutional Court of Lithuania claimed that using a non-Lithuanian way of writing would be contrary not only to the official constitutional language principle but also would complicate the activities of state authorities and other institutions and organizations in the country.[27]

Media

Broadcasting in the minority language is not restricted by the Lithuanian legislation. However, the State Language Law demands (Article 13) that all the audiovisual programs must be shown in state language or with the Lithuanian language subtitles. According to the Law on National Radio and TV (LRT):

“A variety of topics and genres must be ensured in the programs of LRT and the broadcasts must be oriented towards the various strata of society and people of different ages, various nationalities, and convictions.”[28]

The State Language Law (1995) gives national minorities the right to publish information and organize events in their native language alongside the official language (Lithuanian). The Lithuanian state television and radio programs (LRT) also broadcast programs in languages other than Lithuanian and books and newspapers are available in the languages of the national minorities. Article 2 of the Law on Minorities lies down the right to have newspapers, other publications, and information in one’s own language.

However, it has to be strictly noticed that from 2014 (the Ukrainian crisis) all “Putinist media propaganda” on TV and radio coming from Russia is strictly forbidden. Even the personal bank accounts by the law are checked for the reason to “prevent money laundering” but in fact to receive any financial support or donation from Russia. In other words, all taxpayers are legally obliged to declare all incomes coming from abroad to the bank account with the specification of the country. Even the banks are legally mandated to inform the State Taxation Inspection (VMI) about the private incomes from abroad. Those personalities who are getting any financial income from the Russian Federation by any means (for instance, PayPal) are going to be in certain troubles.

National minorities, for instance, published in the 2002 year some 41 periodicals in their language – 35 newspapers and 6 magazines. 31 of them were published in Russian, 7 in Polish, 1 in Belorussian, and 2 in German. The state radio broadcasts one hour daily in Russian and Polish (concerning political news it is pure Russophobic propaganda especially since 2014). There are weekly editions in Ukrainian and Belorussian.[29] It was no and still, there are no Romani-owned or Romani (Gypsi) language newspapers, television, or radio programs in Lithuania at present, and to date, the Government has provided no financial support for the Romani (Roma/Gypsi) language media.[30]

For example, the Polish minority in Lithuania makes active use of the rights provided by the law: witness the publication of one daily newspaper “Kurier Wileński” as well as the weekly “Nasz czas” , the Catholic weekly “Tygodnik Wileńszczyzny”, the quarterly “Znad Wilii”, the monthly magazine for Poles in Lithuania “Magazyn Wileński”: all published in Vilnius and providing a rather broad spectrum of information for the Polish-speaking population of Lithuania. There is one radio station, “Znad Wilii”, broadcasting in Polish from Vilnius/Wilno 24 hours a day. The national Lithuanian radio and TV (LRT) broadcasting company translates a TV program into Polish for 15 minutes once a week. The Polish-speaking population in and around Vilnius is also able to receive some TV stations from Poland (TV Polonia).[31]

Although, according to the researches made by Arturas Tereškinas, and earlier researches are done by Inga Nausėdienė and Giedrius Kadziauskas, the Lithuanian mass media strengthen negative stereotypes of ethnic minorities and present ethnic minorities as a separate part of the Lithuanian society. Discourse analysis of the main Lithuanian dailies and a sample analysis of prime-time TV programs demonstrated that there is a lack of in-depth reporting on ethnic minorities in the Lithuanian mass media. Minority groups share relative invisibility and one-sided stereotypical representations:

„Close reading of the most popular daily and TV programs reveals undercurrent xenophobia in a large part of news reports and broadcasts. The ‚bad news‘ focus is overwhelming: Most newspaper reports and TV broadcasts focus on some minority members who committed a crime. Much less attention is paid to stories about minorities experiencing problems, prejudice, racism, or unemployment.“[32]

In A. Tereškinas’s researches, portraits of different minority groups were examined. The Roma/Gypsi people merit the worst representations as to the least socially integrated, criminal, and exotic group. The mass media frequently refer to the Roma minority as criminal, deviant, socially insecure, inscrutable, and manipulative. In the police reports published in newspapers, the ethnicity of Roma is always emphasized. Paradoxically, there appeared quite recently a set of positive stereotypes attributable to the Roma: The Romani/Gypsies have been shown as passionate, romantic, and very musical.

The ethnic Russians receive mixed coverage in the Lithuanian mass media. On one hand, they are shown as active participants in Lithuanian political life. On other hand, their political behavior is described as threatening and serving the interests of foreign powers (Putin’s Russia). As in the case of the Roma, news reports about crimes stress the Russian nationality of criminals.

The representations of the Polish minority focus on the extremely politicized problem of education. From these representations, the Poles emerge as a self-conscious national minority that requires special status and rights.

A conclusion can be made that TV programs, unfortunately, indicate the minimal presence of ethnic stories and characters in mainstream programming. Ethnic minorities are still hardly ever mentioned in the major broadcast news programs. This fact demonstrates that television fails to mirror the „real“ proportion of Russians, Poles, or Roma in the population of Lithuania. The Lithuanian mass media usually describe ethnic minorities as problematic and not as a positive quality of a multicultural society. Stereotypical attitudes towards minorities threaten to develop social distances (segregation/stratification) between different ethnic groups.[33]

Education

According to the Lithuanian Law on Education, article 28, paragraph 7:

“In localities where a national minority traditionally constitutes a substantial part of the population, upon that community’s request, the municipality assures the possibility of learning in the language of the national minority”.

The Law on Education (1991, amended in 2003) states that educational institutions must incorporate information on ethnic cultures into their curricula and that national minorities should have access to pre-and post-grade schools funded by the state, including lessons on their own language. According to the data of the Ministry of Education and Science, for instance, in the 2003−2004 academic year, there were 1816 schools of general education in Lithuania, among them 1616 in the Lithuanian language, 142 in the Russian, Polish, and Belorussian educational languages and 59 mixed schools with classes of different educational languages.[34]

After the re-establishment of the independence of the Lithuanian state in 1990, the network of Polish schools in South-East Lithuania was upheld. In the 1990s, as more and more the Russian-language schools were closed, the network was extended upon active lobbying of the Lithuanian Polish organizations. The result of such consolidation is the growing number of Polish-mother tongue children attending schools with Polish as the language of instruction. The so-called Polish schools in the area around the capital of Lithuania, where the overwhelming majority of the Lithuanian Poles live, are usually monolingual, with only Lithuanian language as a compulsory subject taught in Lithuanian. It has to be stressed that the Law on Education allows the teaching of other subjects in the Lithuanian language if the parents of the pupils or the pupils themselves wish so.[35]

Outside of compact Polish settlement areas, Saturday or Sunday schools provide instruction in the Polish language and culture. In 2005, there were 11 such Saturday/Sunday schools for the Polish-speaking children in the Kaunas, Klaipėda, and Kėdainiai Districts as well as in other minor regions. These are maintained by local Polish organizations, mainly by the Association of Poles in Lithuania.

In general, In Lithuania, there are most Polish-language schools in Europe after Poland. Together with Poland, Lithuania is the only country in which Polish speakers can get an education in their own national language from elementary school to university (if studying the Polish language and philology at the university). To study the Polish language in Lithuania is possible at three universities in Vilnius. According to the official data, there is 51 school in which the language of instruction is the Polish (67 per cent); 12 schools of Lithuanian-Polish language (16 per cent); 7 schools of the Polish and the Russian language (9 per cent); and 6 schools of the Lithuanian, the Polish, and the Russian language (8 per cent).[36]

The Law on Minorities guarantees minority groups the rights:

“to obtain aid from the state to develop culture and education; to have schooling in one’s native language, with provision for pre-school education, other classes, elementary and secondary school education, as well as provision for groups, faculties and departments at institutions of higher learning to train teachers and other specialists needed by ethnic minorities.”

The Law on Education also provides protection for “compact” minority communities. Although the requisite size and concentration for a “compact” community are not specified in the law, the state will either establish or support existing pre-schools and schools or classes of general education in minority languages and culture to communities it defines as such.

Smaller minority communities without the resources or numbers to establish their own schools may establish separate classes, optional classes, or Sunday school classes within the Lithuanian state schools to learn or improve their knowledge of their native language and culture. The Polish and Russian minorities both benefit from the existence of state-funded schools at which they can study in their mother tongues.[37]

Political representation

Lithuania has three political parties based on minority ethnic denomination: 1) The Union of the Russians in Lithuania; 2) The Alliance of Lithuanian Citizens (supported by the ethnic Russians), and 3) The Election Action of Lithuanian Poles.[38]

It has to be stressed that in Lithuania, there are no legal regulations guaranteeing representation of the minorities in the national Parliament (Seimas) or in the local (municipalities) councils (the so-called, “positive discrimination”).[39] For example, the minority party as every other must get at least 5% of votes in elections to the Parliament to have representation there. However, in neighboring Poland, these parties have the privilege at the elections as the election threshold does not apply to minority groups.[40]

The Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania is a centrist political party in Lithuania that represents the Poles of Lithuania. For instance, at the parliamentary elections on October 11th, 2008, the party won 4.8% of the popular vote and 3 out of 141 seats in the Seimas. One of its leaders – Waldemar Tomaszewski was a candidate in presidential elections in 2009 won by Lithuanian nationalist and Russophobe Dalia Grybauskaitė. However, he managed to get 4,74% of the votes, that was a good result. He was fourth out of seven candidates. The score suggests that the Polish community in Lithuania is well integrated with high national consciousness as nearly all Poles were voting for their compatriot. W. Tomaszewski won in the Vilnius District, where he received 49,31% of the votes, and in the Šalčininkai District with 65% of the votes. The Vilnius District had also a good turnout in the presidential elections. The turnout in the whole of Lithuania was about 52%, and in the Vilnius District, it was 55,42% and in Šalčininkai – 56,57%[41]. In these regions, Poles are a majority, which can be a sign of a quite high citizen consciousness of the Polish minority.

At that time, the Polish minority had 3 representatives in the Lithuanian Parliament. Waldemar Tomaszewski, Michał Mackiewicz, and Jarosław Narkiewicz (of course as a Valdemar Tomaševski, Michal Mackevič, and Jaroslav Narkevič) were elected in the single-mandate constituencies in Vilnius-Šalčininkai, Vilnius-Širvintos, and Vilnius-Trakai. Their presence in the Parliament was although questioned by some other MPs because they possessed the Polish Card. This document confirms belonging to the Polish nation of those people who do not possess Polish citizenship (in Lithuania, double citizenship is illegal).[42] It gives the owner some privileges, like the right to use Polish healthcare, a study in Poland without tuition, work, and trade in Poland. However, in the opinion of some members of the Lithuanian Parliament (usually of the nationalistic-clerical conservatives), ownership of this card is making loyalty to the Lithuanian country doubtful. If the Constitutional Tribunal would decide that the Polish Card can be treated as a commitment to other countries, the Polish deputies could have lost their mandates in the Lithuanian Seimas. According to Lithuanian law, the people who are connected with other countries by some obligations cannot be members of the Lithuanian Parliament. Nevertheless, the Polish Card as a document does not establish any commitment to Poland – a decision of the court agrees with this. Therefore, the opinion of certain (nationalistic-clerical) MPs, who questioned it can be treated as a Lithuanian political provocation toward minority representatives, showing distrust to them and even questioning their legal rights based on the international conventions and treaties.[43]

The social distance on an ethnic basis

According to several prominent researchers, the ethnic Lithuanians proved in the practice to be quite selective in their relationships with other ethnicities in comparison to the Russians or the Poles of Lithuania. It exists a high rate of ethnic Lithuanians claiming they are able always to recognize a person of different ethnic background. Contrary, a big number of Lithuania’s ethnic Poles and Russians are declaring they do not notice a personal identity on an ethnic basis. This practice is confirmed by other international research results as well as like by the European Value Survey which also revealed that the ethnic Lithuanians are practicing higher ethnic closure by declaring (43 per cent) that ethnicity of spouses matters for the luck of marital life (51 per cent think it is not important), while between 70 and 74 per cent of Russians and Poles think it does not matter. On one hand, it can be noticed some differences in the levels of closure or tolerance, but the hierarchy of disliked ethnic groups is very similar for all of the ethnic groups either of the majority or minorities. Nevertheless, selective dislike is unifying all the groups against the most disliked ethnic categories such as Romani/Gypsies, Jews, or Muslims.

The categories of identity that have been disliked remained stable during the 1990s. The negative reaction to other disliked ethnic categories like drug-addicts or former criminals has changed, but the items of disliked identity remained on the same level and even in the same order. It can be linked to the high level of intolerance for the identity categories to the high prevalence of ethnic recognizing that exists regularly. The official data on social connections and life is showing the ethnic isolation of some of the social segments on the ethnic ground. Despite the current preconditions for the assimilation within the policy of equal rights, certain groups are in the sphere of employment isolated or segregated on the ethnic ground (usually Roma). As a matter of fact, this is primarily a situation on a small scale family business. Another fact is that a lot of ethnic Poles and Russians are working in a monoethnic environment. According to several surveys, some 13 per cent of Poles and Russians, 21 per cent of Jews, or 17 per cent of Muslim Tatars do not have ethnic Lithuanians as their personal friends.

As it is well known, the participation in social life is one of the focal factors in the adaptation and integration of minority groups. In this sense, Lithuania’s ethnic Russians exhibit a striking difference concerning social participation and are the most passive ethnic group. Nevertheless, the lack of participation in social life may result in the marginalization of a big number of the population even to lead to social ghettoization.

Around 20 percent of ethnic minority members believe that it is of extreme importance to be Lithuanian in order to get a good job. Many of those who experienced a certain kind of violation of their rights as the members of the minority group experienced it in the sphere of employment. It means that in reality exist unequal chances for minorities during the process of adaptation and integration.

Social adaptation and integration

Social adaptation and integration can be understood as processes of the combination of an individual’s aspirations and/or expectations with his/her possibilities and expectations and the requirements of society (i.e., of the majority population). It has to be stressed that in principle understanding both adaptation and integration in broader terms is significant as a person may have not only more but also quite different aims than acquiring a particular civil or national identity. In other words, a minority population may have wishes differently than the majority wants to see as, for instance, instead of active loyalty to the state, a minority may only wish to have social security. Therefore, civil virtues may be of secondary importance.

Lithuania’s ethnic Russians exhibit the conventional features of an ethnic group less than others: They identify less strongly with categories such as territory, co-ethnics in the country, and co-believers. During the last two decades, there is a tendency of religious revival, and it was considered that the Christian Orthodoxy could become the unifying factor for the Russian community, but for different reasons, such expectation did not come true, unlike in pre-WWII Lithuania.

The worsened social status and general civic passivity among ethnic Russians in Lithuania are clear signs that there are more common problems of adaptation and integration but not an only identity crisis. The greatest contrast in comparison to the majority group is the low social and political status and low education of the Russians. It practically means that both adaptation and integration of ethnic Russians in the post-Soviet Lithuania is directly related to their social-political status.

In the Jewish case in Lithuania, two facts are crucial: 1) The Jews surveyed did not mention religious identity; and 2) The identification with the territorial aspects of the country is relatively weak. Therefore, the Jewish way of adaptation and integration is basically within the same framework as the Russian one. This similarity can be related to the experience of both Jews and Russians as migrants of the Soviet time. However, differently to the Russian case, there is a high level of professional identity among the Jews that is probably in direct connection with their higher level of education.

Ethnic (Muslim) Tatars (like the Jews) are relatively more active in their ethnic organizations. Nevertheless, their attitudes are not always the same as it depends on the living region. For instance, the Tatars living in Vilnius, who are more often the descendants of a historical diaspora, exhibit a higher level of assimilationist attitude to the Lithuanian society.

Poles, probably because of the historical reasons, experienced smaller obstacles in their adaptation and integration as there are no feelings among them of some backing of their ethnic group compared with the Lithuanian majority (it can be only vice versa).[44] Strong identification with its own ethnic living area can be proof of the strong consolidation of the Polish ethnic minority in Lithuania which has a strong religious (the Roman Catholic) identity, but give not so high importance to education and instead rather emphasizing their social background and links with co-ethnics especially concerning the finding a prosperous job position. The ethnic Poles have the highest rate of ethnic Lithuanians among the relatives – the fact which is very contradicting a wrong opinion about the strong segregation of the ethnic Poles from the rest of society. However, on the other hand, the Poles who considered themselves to be a typical representative of the ethnic group are the real social separatists.

In general, the crucial differences between larger ethnic groups in Lithuania versus historical diasporas are noticeable in the strength of ethnic ties with other group members. The ethnic Russians still experience an identity crisis and are likely to become a minority from a sociological viewpoint. The Poles tend to have the most similar attitudes to those of ethnic Lithuanians and, therefore, the Poles can be the most successfully integrated ethnic group.

Conclusions

This article tried to present some basic areas of life, which are most important when it comes to minority issues. Language is one of the most powerful identity-building tools. The right to use it in everyday life, but also in media, and the public sphere is the most important thing for a national minority to preserve its’ identity and customs. The law of the Republic of Lithuania gives linguistic rights for minorities existing on its’ territory and the possibility to learn at school in their mother-language in different ways. The minorities have also the right to create organizations based on nationality and to be represented in the governmental authorities.

According to the legal documents and law, Lithuania is a country that fully respects the rights of people from different ethnic groups. The legal framework is politically correct and at the main points adjusted to international conventions. However, the deeper insight into the real situation shows some controversies and problems, when it comes to the issue of minorities in Lithuania. With every issue that I wrote about, I tried to present not only the legal framework but also some problems with putting it into practice. The example of using bilingual names of places was one of the most glaring. It shows that the existence of the law is not enough to make it works, especially when other, contradictory law is treated as a superior (an example of the collision between the Law on National Language and the Law on Ethnic Minorities). The realization of legal rights is also obstructed by some stereotypes, historical animosities, and a lack of trust and tolerance towards groups of other nationalities.

There are still many problems, which were even not presented in the article. Some opinion of the Polish minority leaders shows a lack of satisfaction with a present situation concerning the position and protection of the Poles in Lithuania. This article, for example, did not even deal with controversies like land reprivatization, which is also an important issue in majority-minority relations and can be called battlefield relations. Because of the special position of minority members in the social structure, these groups meet also problems connected with their social status. It can be the result of factors like place of living (the Polish minority lives mainly in the villages) or a level of education (Romani minority).

There is like the general practical rule that national minorities are always under some pressure of assimilation from the majority. On other hand, the laws, which regulate the rights of the national minorities are usually favorable for them in most European countries (the same is with Lithuania). That is why much depends on the ability of national minorities to protect their rights. In Lithuania, many organizations try to represent the interests and protect the rights of the national minorities but they are disunited and not presentable. It must be noted that the Polish national minority is more effective in a political sense than the Russian one, but it is not very numerous and so its political influence is limited. The actions of more organized and united work would help national minorities in Lithuania to protect better their rights and to get bigger support from the motherland.[45]

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

sotirovic1967@gmail.com

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

[1] About minority rights in general, see in [Will Kymlicka (ed.), The Rights of Minority Cultures, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2000].

[2] Thomas Benedikter, Legal Instruments of Minority Protection in Europe – An overview:

http://www.gfbv.it/3dossier/eu-min/autonomy-eu.html

[3] About the protection of minorities by international law, see more in [G. Pentassuglia, Minorities in International Law: Minority Issues Handbook, Strasbourg: CoE, 2002].

[4] This definition is based on UNO’s understanding of minorities. See more in [Pan Christoph, Beate Sibylle Pfeil, National Minorities in Europe, I−II].

[5] Thomas Benedikter, Legal Instruments of Minority Protection in Europe – An overview:

http://www.gfbv.it/3dossier/eu-min/autonomy-eu.html

[6] Tatars and Karaims are the most „exotic” minorities in Lithuania. Both of them appeared on the present-day territory of Lithuania in 1398 when upon returning from battle in the Crimea, Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas the Great (1392−1430) settled Tatars and Karaims, both soldiers as prisoners of war and civilians (their families) in a free area of New Trakai – a town some 30 km. far from Vilnius. One part of them was settled in Vilnius as well. It is known from the sources that the number of Karaim families was 383. Both Tatars and Karaims received important privileges from the ruler. They were protecting the town, the castle-residence of the ruler, being his body guars and professional soldiers while their families have been involved in different types of economy. It was formed in New Trakai small residential quarters of Tatars and Karaims with their sanctuaries: Tatar mosque and Karaim kenessa. Karaims are an ethnic Turkish group belonging to the oldest Kipchak tribe that came from Central Asia, and which never had its state. At the end of the 20th century, there were some 3.700 Karaims worldwide (Russia, Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine) of whom in Lithuania lived 300. Karaim religion is a branch of Judaism that recognizes the Old Testament without any rabbinic explanations. They use both Hebrew and Karaim during worship. During the Soviet time, kenessa in New Trakai was the only temple of worship for Karaims in Europe, like all other kenessas (including and kenessa in Vilnius) in the USSR have been closed down. Tatars were brought to Lithuania together with Karaims in 1398 and settled in New Trakai near the southern and western entrances to the town apart of those settled in Vilnius. They not only guarded the town, carried out their army obligations with each household providing an armed horseman with their funds, but also helped in diplomatic relations with different peoples beyond the Volga River such as in Kazan, or the Crimea. Later, the Tatars raised horses and traded in vegetables. In 1609 a big crowd of fervent Roman Catholics gathered in New Trakai and destroyed the local mosque, which never became rebuilt. The Tatars from New Trakai moved to Vilnius. It is estimated that today, around 3.500 Tatars are living in Lithuania who are Sunni Muslims and do not use their language anymore [Karolina Mickevičiūtė, Trakai. A Guide Through the Historical National Park, Vilnius: Briedis, 2013, 20−21; Tautinės bendruomenės Lietuvoje, Vilnius: Tautinių mažumų departamentas prie Lietuvos Respublikos vyriausybės, 2018, 47−48, 64−65].

[7] See, for instance [Zigmantas Kiaupa, Jūratė Kiaupienė, Albinas Kuncevičius, The History of Lithuania Before 1795, Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2000; Arūnas Gumuliauskas, Lietuvos istorija (1795−2009). Studijų knyga, Šiauliai: Licilijus, 2010].

[8] Giedre Jankevičiūtė, Lithuania. Guide, Vilnius: R. Paknio Leidykla, 2016; See in more details, for instance in [Arvydas Matulionis et at., The Russian Minority in Lithuania, Research Report #8, ENRI-East Research Project, 2013].

[9] Tautinės bendruomenės Lietuvoje, Vilnius: Tautinių mažumų departamentas prie Lietuvos Respublikos vyriausybės, 2018, 5.

[10]Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania, Vilnius: Statistical Department, 2008.

[11] Giedre Jankevičiūtė, Lithuania. Guide, Vilnius: R. Paknio Leidykla, 2016.

[12] Tautinės bendruomenės Lietuvoje, Vilnius: Tautinių mažumų departamentas prie Lietuvos Respublikos vyriausybės, 2018, 5.

[13] About recent conditions of human rights in Lithuania, see in [Karolis Liutkevičius et al, Human Rights in Lithuania 2016−2017. Overview, Vilnius: Human Rights Monitoring Institute, 2018].

[14] The Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania, several editions.

[15] Stasys Samalavičius, An Outline of Lithuanian History, Vilnius: Diemedis leidykla, 1995, 158−159; Tomas Venclova, Vilnius. City Guide, Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 2018, 69.

[16] Mercator-Education, The Polish Language in Education in Lithuania, 2006.

[17] Lietuvos lenkai: Faktai, skaičiai, veikla, Tautinės bendruomenės Lietuvoje, Vilnius: Tautinių mažumų departamentas prie Lietuvos Respublikos vyriausybės, 2017.

[18] Marko Kallonen, Minority Protection and Linguistic Rights in Lithuania.

[19] Mercator-Education, The Polish Language in Education in Lithuania. About the rights of ethnic minorities in general, see in [Inga Abramavičiūtė et al, Tautinių mažumų teisės, Vilnius: Lietuvos žmogaus teisių centras, 2005].

[20] The Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania, several editions.

[21] Jan Sienkiewicz, Przestrzeganie praw polskiej grupy etnicznej w Republice Litewskiej:

http://www.wspolnota-polska.org.pl/index.php?id=pwko91

[22] The official English language text of the Constitution can be found at the website of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Lithuania [https://www.lrkt.lt/en/about-the-court/legal-information/the-constitution/192]. The Constitution was adopted by the citizens of the Republic of Lithuania in Referendum on October 25th, 1992. It has 154 articles. About the historical development of Lithuanian Constitutionalism, see in [Dainius Žalimas (Editor-in-Chief), Lithuanian Constitutionalism: The Past and the Present, Vilnius, 2017].

[23] Mercator-Education, The Polish Language in Education in Lithuania.

[24] Post address: Naugarduko g. 76, LT-03202 Vilnius, Lietuva.

[25] Zbigniew Kurcz, Mniejszość polska na Wileńszczyźnie, Wrocław 2005.

[26] About the identity problems in Lithuania of three biggest ethnic minorities, see in [Monika Frėjutė-Rakauskienė, Kristina Šliavaitė, „Rusai, lenkai, baltarusai Lietuvoje: lokalaus, regioninio ir europinio identitetų sąsajos“, Etniškumo studijos, 1−2, Lietuvos socialinių tyrimų centro Etninių tyrimu institutas, Vilnius, 2012, 126−144].

[27] Wikipedia. Autor: Robert Wielgórski; „Premier popiera pisownię nazwisk w języku mniejszości narodowych”, article from daily newspaper Kurier Wileński, 2009-04-23.

[28] Marko Kallonen, Minority Protection and Linguistic Rights in Lithuania.

[29] Arturas Tereškinas, “Minority Politics, Mass Media and Civil Society in Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland“: http://www.policy.hu/tereskinas/Research2002.html

[30] “Minority Protection in Lithuania”, Monitoring the EU Accession Process: Minority Protection, Budapest: Open Society Insitute, 2001; TV Programos Savaitė: 2020-09-19.

[31] Mercator-Education, The Polish Language in Education in Lithuania.

[32] Arturas Tereškinas, “Minority Politics, Mass Media and Civil Society in Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland“: http://www.policy.hu/tereskinas/Research2002.html

[33] Ibid. For the matter of comparison, see [Invisible Visible Minority: Confronting Afrophobia and Advancing Equality for People of African Descent and Black Europeans in Europe, Brussels: European Network Against Racism, 2014].

[34]„Lithuania/4.2 Recent Policy Issues and Debates”: www.culturalpolicies.net

[35] About ethnicity and identities in South-East Lithuania, see in [Monika Frėjutė-Rakauskienė et al, Etniškumas ir identitetai pietryčių Lietuvoje: Raiška, vieksnniai ir kontektai, Vilnius: Lietuvos socialinių tyrimų centras, 2016].

[36] Tautinės bendruomenės Lietuvoje, Vilnius: Tautinių mažumų departamentas prie Lietuvos Respublikos vyriausybės, 2018, 54.

[37] About the importance of language for the preservation of national identity in Europe, see in [Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2000].

[38] Marko Kallonen, Minority Protection and Linguistic Rights in Lithuania.

[39] See more in [Leslie Green, „Internal Minorities and thier Rights”, Will Kymlicka (ed.), The Rights of Minority Cultures, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 256−274].

[40] See more in [Miroslaw Matyja, The System of Direct Democracy in Poland: Based on the Swiss Political Model, LAP LAMBERT, 2020].

[41] According to the information from the Polish Press Agency.

[42] What concerns the citizenship, in 1994 Lithuania contained some 81.3 per cent of the population who spoke Lithuanian as their first language, with additional ethnic groups who spoke primarily Polish and Russian as their first languages. The language requirements have not been particularly stringent when related to citizenship in Lithuania. However, it was not possible for ethnic Russians who applied to become citizens of the Republic of Lithuania to hold at the same time and the citizenship of the Russian Federation. Besides, they had to sign a loyalty statement in which they expressed respect for Lithuania’s language, culture, traditions, and customs [L. Barrington, „The Domestic and International Consequences of Citizenship in the Soviet Successor States”, Europe-Asia Studies, 47, 1995, 733].

[43] See more in [Legal Aspects of the Rights of National Minorities, Seminar, Zagreb, Croatia, December 4−5th, 2000, Zagreb: Office for National Minorities of the Government of the Republic of Croatia].

[44] About a general history of Lithuania, see in [Zigmantas Kiaupa, Jūratė Kiaupienė, Albinas Kuncevičius, The History of Lithuania Before 1795, Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2000; Arūnas Gumuliauskas, Lietuvos istorija (1795−2009). Studijų knyga, Šiauliai: Licilijus, 2010].

[45] About the integration of ethnic minority groups in Lithuania, see in [Natalija Kasatkina, Tadas Leončikas, Lietuvos etninių grupių adaptacija: Kontekstas ir eiga, Vilnius: Eugrimas, 2003].

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS