Views: 1918

Columbus made four voyages to the New World. [1] The initial voyage reveals several important things about the man. First, he had genuine courage because few ship’s captains had ever pointed their prow toward the open ocean, the complete unknown. Secondly, from numerous of his letters and reports we learn that his overarching goal was to seize wealth that belonged to others, even his own men, by whatever means necessary.

Columbus’s Spanish royal sponsors (Ferdinand and Isabella) had promised a lifetime pension to the first man who sighted land. A few hours after midnight on October 12, 1492, Juan Rodriguez Bermeo, a lookout on the Pinta, cried out — in the bright moonlight, he had spied land ahead. Most likely Bermeo was seeing the white beaches of Watling Island in the Bahamas.

As they waited impatiently for dawn, Columbus let it be known that he had spotted land several hours before Bermeo. According to Columbus’s journal of that voyage, his ships were, at the time, traveling 10 miles per hour. To have spotted land several hours before Bermeo, Columbus would have had to see more than 30 miles over the horizon, a physical impossibility. Nevertheless Columbus took the lifetime pension for himself. [1,2]

Columbus installed himself as Governor of the Caribbean islands, with headquarters on Hispaniola (the large island now shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic). He described the people, the Arawaks (called by some the Tainos) this way:

“The people of this island and of all the other islands which I have found and seen, or have not seen, all go naked, men and women, as their mothers bore them, except that some women cover one place only with the leaf of a plant or with a net of cotton which they make for that purpose.

“They have no iron or steel or weapons, nor are they capable of using them, although they are well-built people of handsome stature, because they are wondrous timid…. [T]hey are so artless and free with all they possess, that no one would believe it without having seen it.

“Of anything they have, if you ask them for it, they never say no; rather they invite the person to share it, and show as much love as if they were giving their hearts; and whether the thing be of value or of small price, at once they are content with whatever little thing of whatever kind may be given to them.” [3, pg.63; 1, pg.118]

Added note:

In an ominous foreshadowing of the horrors to come, Columbus also wrote in his journal:

“I could conquer the whole of them with fifty men, and govern them as I pleased.”

After Columbus had surveyed the Caribbean region, he returned to Spain to prepare his invasion of the Americas. From accounts of his second voyage, we can begin to understand what the New World represented to Columbus and his men — it offered them life without limits, unbridled freedom.

Columbus took the title “Admiral of the Ocean Sea” and proceeded to unleash a reign of terror unlike anything seen before or since. When he was finished, eight million Arawaks — virtually the entire native population of Hispaniola — had been exterminated by torture, murder, forced labor, starvation, disease and despair. [3, pg.x]

A Spanish missionary, Bartolome de las Casas, described first-hand how the Spaniards terrorized the natives. [4] Las Casas gives numerous eye-witness accounts of repeated mass murder and routine sadistic torture.

As Barry Lopez has accurately summarized it,

“One day, in front of Las Casas, the Spanish dismembered, beheaded, or raped 3000 people.

‘Such inhumanities and barbarisms were committed in my sight,’ he says, ‘as no age can parallel….’

“The Spanish cut off the legs of children who ran from them. They poured people full of boiling soap. They made bets as to who, with one sweep of his sword, could cut a person in half. They loosed dogs that ‘devoured an Indian like a hog, at first sight, in less than a moment.’ They used nursing infants for dog food.” [2, pg.4]

This was not occasional violence — it was a systematic, prolonged campaign of brutality and sadism, a policy of torture, mass murder, slavery and forced labor that continued for CENTURIES.

“The destruction of the Indians of the Americas was, far and away, the most massive act of genocide in the history of the world,” writes historian David E. Stannard. [3, pg.x]

Eventually more than 100 million natives fell under European rule. Their extermination would follow. As the natives died out, they were replaced by slaves brought from Africa.

To make a long story short, Columbus established a pattern that held for five centuries — a “ruthless, angry search for wealth,” as Barry Lopez describes it.

“It set a tone in the Americas. The quest for personal possessions was to be, from the outset, a series of raids, irresponsible and criminal, a spree, in which an end to it — the slaves, the timber, the pearls, the fur, the precious ores, and, later, arable land, coal, oil, and iron ore — was never visible, in which an end to it had no meaning.”

Indeed, there WAS no end to it, no limit.

As Hans Koning has observed,

“There was no real ending to the conquest of Latin America. It continued in remote forests and on far mountainsides. It is still going on in our day when miners and ranchers invade land belonging to the Amazon Indians and armed thugs occupy Indian villages in the backwoods of Central America.” [6, pg.46]

In the 1980s, under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush, the U.S. government knowingly gave direct aid to genocidal campaigns that murdered tens of thousands Mayan Indian people in Guatemala, El Salvador and elsewhere. [7]

The pattern holds.

Added note:

And still, in 2003, the genocide continues in Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala.

Continuing the gruesome tradition of the 1980s, which also terrorized the people of Nicaragua, U.S. government-funded fascist paramilitaries mass-murder Indians in Central and South America to this day. The bestial carnage committed by Uncle Sham’s proxy armies includes countless disappearances, epidemic rape and torture. The Colombian paramilitaries have even made their own gruesome addition to the list of horrors: public beheadings.

This latest stage of the American Indian holocaust is enthusiastically supported by the cocaine-smuggling CIA, the Pentagon and all the rest of the United States Corporate Mafia Government.

The English/American Genocide

Unfortunately, Columbus and the Spaniards were not unique. They conquered Mexico and what is now the Southwestern U.S., with forays into Florida, the Carolinas, even into Virginia. From Virginia northward, the land had been taken by the English who, if anything, had even less tolerance for the indigenous people.

As Hans Koning says,

“From the beginning, the Spaniards saw the native Americans as natural slaves, beasts of burden, part of the loot. When working them to death was more economical than treating them somewhat humanely, they worked them to death.

“The English, on the other hand, had no use for the native peoples. They saw them as devil worshippers, savages who were beyond salvation by the church, and exterminating them increasingly became accepted policy.” [6, pg.14]

The British arrived in Jamestown in 1607. By 1610 the intentional extermination of the native population was well along. As David E. Stannard has written,

“Hundreds of Indians were killed in skirmish after skirmish. Other hundreds were killed in successful plots of mass poisoning. They were hunted down by dogs, ‘blood-Hounds to draw after them, and Mastives [mastiffs] to seize them.’

“Their canoes and fishing weirs were smashed, their villages and agricultural fields burned to the ground. Indian peace offers were accepted by the English only until their prisoners were returned; then, having lulled the natives into false security, the colonists returned to the attack.

“It was the colonists’ expressed desire that the Indians be exterminated, rooted ‘out from being longer a people upon the face of the Earth.’ In a single raid the settlers destroyed corn sufficient to feed four thousand people for a year.

“Starvation and the massacre of non-combatants was becoming the preferred British approach to dealing with the natives.” [3, pg.106]

In Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey extermination was officially promoted by a “scalp bounty” on dead Indians.

“Indeed, in many areas it [murdering Indians] became an outright business,” writes historian Ward Churchill. [5, pg.182]

Indians were defined as subhumans, lower than animals. George Washington compared them to wolves, “beasts of prey” and called for their total destruction. [3, pgs.119-120]

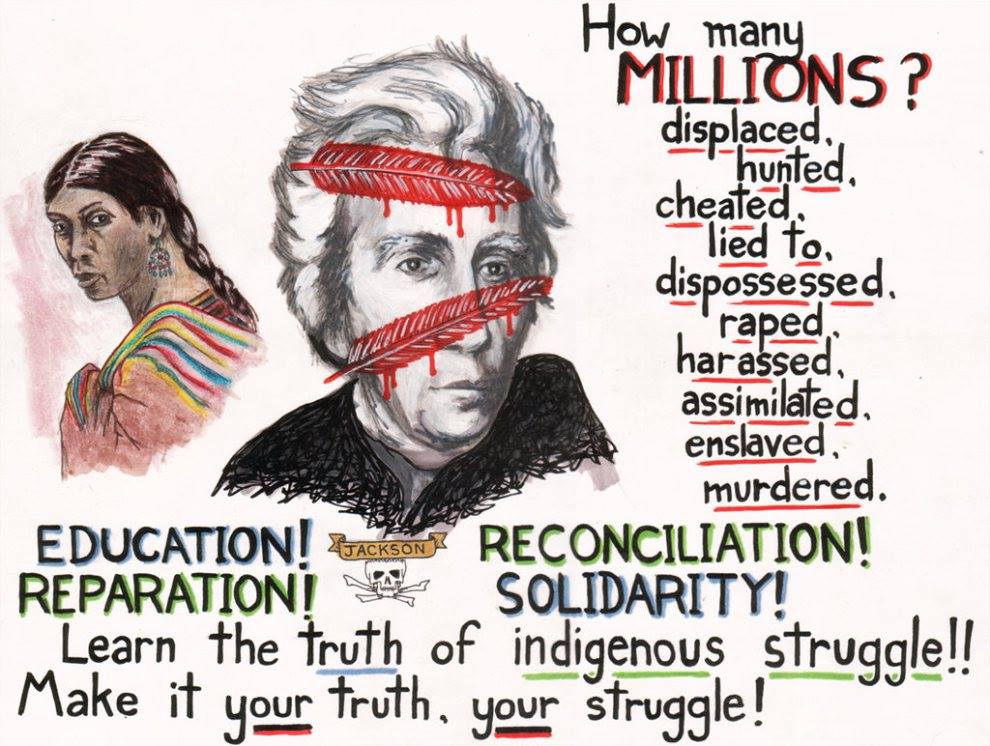

Andrew Jackson — whose [innocent-looking] portrait appears on the U.S. $20 bill today — in 1814:

“supervised the mutilation of 800 or more Creek Indian corpses — the bodies of men, women and children that [his troops] had massacred — cutting off their noses to count and preserve a record of the dead, slicing long strips of flesh from their bodies to tan and turn into bridle reins.” [5, pg.186]

The English policy of extermination — another name for genocide — grew more insistent as settlers pushed westward:

In 1851 the Governor of California officially called for the extermination of the Indians in his state. [3, pg.144]

On March 24, 1863, the Rocky Mountain News in Denver ran an editorial titled, “Exterminate Them.”

On April 2, 1863, the Santa Fe New Mexican advocated “extermination of the Indians.” [5, pg.228]

In 1867, General William Tecumseh Sherman said:

“We must act with vindictive earnestness against the [Lakotas, known to whites as the Sioux] even to their extermination, men, women and children.” [5, pg.240]

In 1891, Frank L. Baum (gentle author of “The Wizard Of Oz”) wrote in the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer (Kansas) that the army should “finish the job” by the “total annihilation” of the few remaining Indians.

The U.S. did not follow through on Baum’s macabre demand, for there really was no need. By then the native population had been reduced to 2.5% of its original numbers and 97.5% of the aboriginal land base had been expropriated and renamed “The land of the free and the home of the brave.”

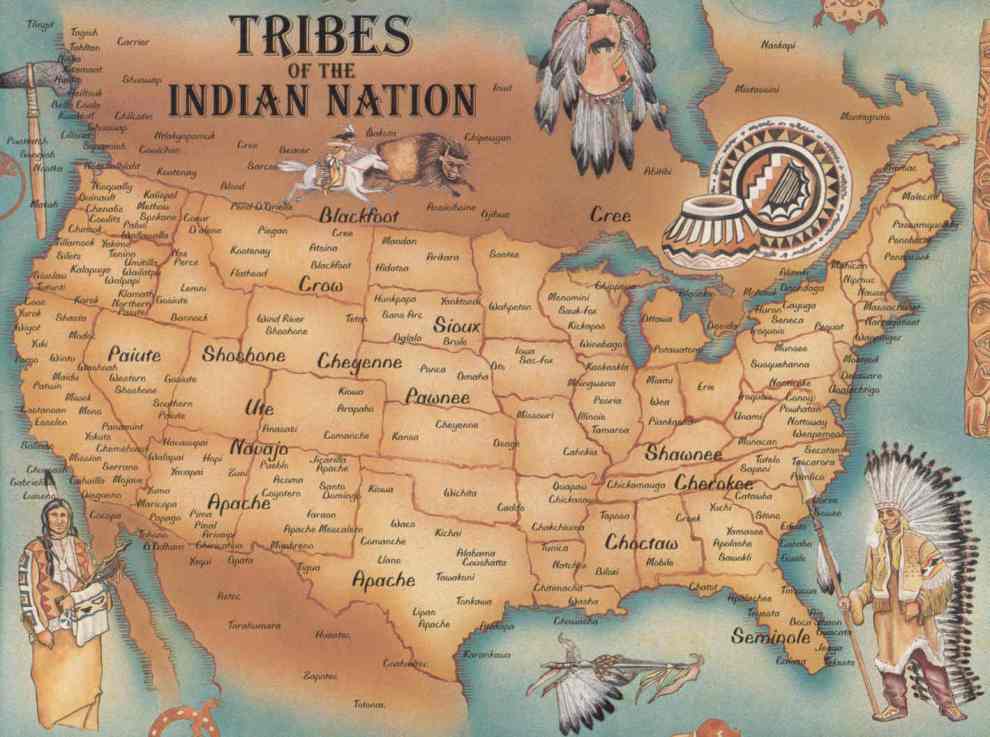

Hundreds upon hundreds of native tribes with unique languages, learning, customs, and cultures had simply been erased from the face of the earth, most often without even the pretense of justice or law.

Today we can see the remnant cultural arrogance of Christopher Columbus and Captain John Smith shadowed in the cult of the “global free market” which aims to eradicate indigenous cultures and traditions world-wide, to force all peoples to adopt the ways of the U.S.

Today’s globalist “Free Trade” is merely yesterday’s “Manifest Destiny” writ large.

But as Barry Lopez says,

“This violent corruption needn’t define us…. We can say, yes, this happened, and we are ashamed. We repudiate the greed. We recognize and condemn the evil. And we see how the harm has been perpetuated. But, five hundred years later, we intend to mean something else in the world.”

If we chose, we could set limits on ourselves for once. We could declare enough is enough.

Notes:

1. J.M. Cohen, editor, The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus

London: Penguin Books, 1969; ISBN 0-14-044217-0

2. Barry Lopez, The Rediscovery of North America

Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1990; ISBN 0-8131-1742-9

3. David E. Stannard, American Holocaust: Columbus and the Conquest of the New World

New York: Oxford University Press, 1992; ISBN 0-19-507581-1

4. Bartolome de las Casas, The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account

translated by Herma Briffault

Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992; ISBN 0-8018-4430-4

5. Ward Churchill, A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas, 1492 to the Present

San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1997; ISBN 0-87286-323-9

6. Hans Koning, The Conquest of America: How The Indian Nations Lost Their Continent

New York: Monthly Review Press, 1993, pg. 46.; ISBN 0-85345-876-6

7. For example, see Mireya Navarro, “Guatemalan Army Waged ‘Genocide,’ New Report Finds,”

NEW YORK TIMES, February 26, 1999, pg. unknown.

The NY Times described “torture, kidnapping and execution of thousands of civilians” — most of them Mayan Indians — a campaign to which the U.S. government contributed “money and training.”

SOURCE OF THIS ARTICLE

The following narrative is by Arthur Barlowe (1584, p.108), describing American Indians.

‘We found the people most gentle loving and faithful, void of all guile and treason, and such as lived after the manner of the Golden Age,…, a more kind and loving people there can not be found in the world.’

His description well fits our categories of Eastern cognitive styles: affiliative, personal, understanding, non-discursive. With predominance of the affective-cognitive belief system making one to marry for love, as contrasted with the cognitive-affective system typical of mental calculations prior to bestowing affection on the ‘loved one.’ Closeness associated with the tactile contact mode. Suspended critical appraisal and present time orientation, acting as limiting factors in carrying hatred ‘beyond the grave.’

David Stannard in his scholarly American Holocaust (1992, p. 232) writes:

From the earliest days of settlement, British men in the colonies from the Carolinas to New England rarely engaged in sexual relations with the Indians, even during those times when there were few if any English women available. Such encounters were viewed as a “horrid crime” and legislation was passed that “banished forever” such mixed race couples, referring to their offspring in animalistic terms.

The estimates of the number of victims of the American Holocaust differ. However, these differences show remarkable similarity with the controversy surrounding the Holocaust deniers who do not deny that Holocaust occurred, but try to diminish its extent. Thus, for instance, R. J. Rummel in his 1994 book Death by Government estimates the number of victims of the centuries of European colonization as low as 2 million.

Among the contemporary Holocaust deniers is also Gary North, who in his Political Polytheism (1989, pp. 257-258) asserts:

Liberals have adopted the phrase “native Americans” in recent years. They never, ever say “American natives,” since this is only one step away from “American savages,” which is precisely what most of those demon-worshipping, land-polluting people were. This was one of the great sins in American life, they say: “the stealing of Indian lands”. That a million savages had a legitimate legal claim on the whole of North America north of Mexico is the unstated assumption of such critics. They never ask the most pertinent question:

Was the advent of the Europeans in North America a righteous historical judgment of God against the Indians?

The European colonization of the Americas forever changed the lives and cultures of the Native Americans. In the 15th to 19th centuries, their populations were ravaged, by the privations of displacement, by disease, and in many cases by warfare with European groups and enslavement by them. The first Native American group encountered by Columbus, the 250,000 Arawaks of Haiti, were enslaved. Only 500 survived by the year 1550, and the group was extinct before 1650.

Europeans also brought diseases against which the Native Americans had no immunity. Chicken pox and measles, though common and rarely fatal among Europeans, often proved fatal to Native Americans, and more dangerous diseases such as smallpox were especially deadly to Native American populations. It is difficult to estimate the total percentage of the Native American population killed by these diseases.

Epidemics often immediately followed European exploration, sometimes destroying entire villages. Some historians estimate that up to 80% of some Native populations may have died due to European diseases.

Sacheen Littlefeather

On March 27, 1973, a young woman took the stage at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, California, to decline Marlon Brando’s Best Actor Oscar. She said that Marlon Brando cannot accept this award because of the treatment of American Indians by the film industry and the recent happenings at Wounded Knee.

Brando had written a fifteen-page speech to be given at the awards by Cruz, but when the producer met her backstage, he threatened to physically remove her or have her arrested if she spoke on stage for more than 45 seconds. The speech she read contained the lines:

Hello. My name is Sasheen Littlefeather. I’m Apache and I am president of the National Native American Affirmative Image Committee.

I’m representing Marlon Brando this evening, and he has asked me to tell you in a very long speech which I cannot share with you presently, because of time, but I will be glad to share with the press afterwards, that he very regretfully cannot accept this very generous award.

[…]

What kind of moral schizophrenia is it that allows us to shout at the top of our national voice for all the world to hear that we live up to our commitment when every page of history and when all the thirsty, starving, humiliating days and nights of the last 100 years in the lives of the American Indian contradict that voice?

In his autobiography Songs my Mother Told Me (1994, pp. 380-402) Marlon Brando, devotes several pages to the genocide of the American Indians, excerpted as follows:

After their lands were stolen from them, the ragged survivors were herded onto reservations and the government sent out missionaries who tried to force the Indians to become Christians. After I became interested in American Indians, I discovered that many people don’t even regard them as human beings. It has been that way since the beginning.

Cotton Mather compared them to Satan and called it God’s work – and God’s will – to slaughter the heathen savages who stood in the way of Christianity.

As he aimed his howitzers on an encampment of unarmed Indians at Sand Creek, Colorado, in 1864, an army colonel named John Chivington, who had once said that thelives of Indian children should not be spared because “nits make lice,” told his officers: “I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians.” Hundreds of Indian women, children, and old men were slaughtered in the Sand Creek massacre. One officer who was present said later, “Women and children were killed and scalped, children shot at their mother’s breasts, and all the bodies mutilated in the most horrible manner. The dead bodies of females were profaned in such a manner that the recital is sickening.

The troopers cut off the vulvas of Indian women, stretched them over their saddle horns, then decorated their hatbands with them; some used the skin of brave’s scrotums and the breasts of Indian women as tobacco pouches, then showed off these trophies, together with the noses and ears of some of the Indians they had massacred, at the Denver Opera House.

Alcohol-Attributable Deaths and Years of Potential Life Lost Among American Indians and Alaska Natives — United States, 2001–2005

Excessive alcohol consumption is a leading preventable cause of death in the United States (1) and has substantial public health impact on American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations (2). To estimate the average annual number of alcohol-attributable deaths (AADs) and years of potential life lost (YPLLs) among AI/ANs in the United States, CDC analyzed 2001–2005 data (the most recent data available), using death certificate data and CDC Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) software.* This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicated that AADs accounted for 11.7% of all AI/AN deaths, that the age-adjusted AAD rate for AI/ANs was approximately twice that of the U.S. general population, and that AI/ANs lose 6.4 more years of potential life per AAD compared with persons in the U.S. general population (36.3 versus 29.9 years). These findings underscore the importance of implementing effective population-based interventions to prevent excessive alcohol consumption and to reduce alcohol-attributable morbidity and mortality among AI/ANs.

ARDI estimates AADs and YPLLs resulting from excessive alcohol consumption by using multiple data sources and methods.† AADs are generated by multiplying the number of sex- and cause-specific deaths (e.g., liver cancer) by the sex- and cause-specific alcohol-attributable fraction (AAF) (i.e., the proportion of deaths attributable to excessive alcohol consumption). For deaths that are, by definition, 100% attributable to excessive alcohol consumption (e.g., alcoholic liver disease), the total number of AADs equals the total number of deaths. For deaths that are <100% attributable to alcohol, ARDI uses either direct or indirect AAF estimates to generate the total number of AADs. Direct AAF estimates typically come from studies that have assessed the proportion of persons dying from a particular condition (e.g., injuries) at or above a specified blood alcohol concentration (e.g., 0.10 g/dL) or from follow-up studies that have assessed alcohol use of the decedents, based on medical record review and interviews with next-of-kin. Indirect AAF estimates are calculated from pooled risk estimates obtained from meta-analyses of mostly chronic conditions, examining the relationship between various alcohol-related health outcomes (e.g., liver cancer) and the population-based prevalence of alcohol use at consumption levels (i.e., low, medium, or high).

For this analysis, death certificate data for 2001–2005 were used to determine the average annual number of deaths from alcohol-related causes for all AI/ANs in the United States and for the U.S. population as a whole. Population-specific, direct AAF estimates for motor vehicle traffic crashes were obtained from the Fatality Analysis and Reporting System§ by averaging 2001–2005 data for AI/ANs and the U.S. population. Population-based prevalence estimates of alcohol consumption were obtained by averaging 2001–2005 data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System¶ and were used to calculate all indirect AAFs. AADs were analyzed by cause and stratified by sex and by age, using standard 5-year age groupings. YPLLs were generated by multiplying the age- and sex-specific AADs by the corresponding life expectancies. Death and life expectancy data were obtained from the National Vital Statistics System.** Death records missing data on decedent age or sex were excluded from this analysis. Bridged-race population estimates from the U.S. Census were used to calculate death rates. Death rates were directly age adjusted to the standard 2000 U.S. population using the age groups 0–19, 20–34, 35–49, 50–64, and >65 years.

During 2001–2005, an average of 1,514 AADs occurred annually among AI/ANs, accounting for 11.7% of all deaths in this population (Table). Overall, 771 (50.9%) of average annual AADs resulted from acute causes, and 743 (49.1%) from chronic causes. The leading acute cause of death was motor-vehicle traffic crashes (417 AADs), and the leading chronic cause was alcoholic liver disease (381). The crude AAD rate among AI/ANs was 49.1 per 100,000 population (25.0 for acute causes and 24.1 for chronic causes). Of all YPLLs, 60.3% resulted from acute conditions, and 39.7% resulted from chronic conditions. The leading acute cause of YPLLs was motor-vehicle traffic crashes (34.4% of YPLLs), and the leading chronic cause was alcoholic liver disease (21.2%).

Overall, 68.3% of AAD decedents among AI/ANs were men, and more AADs occurred among men than women in all age groups (Figure 1); 65.9% of AADs were among persons aged <50 years, and 6.9% were among persons aged <20 years. Of the YPLLs, 68.3% were among those aged 20–49 years.

By Indian Health Service statistical region, the greatest number of AADs occurred in the Northern Plains (497 AADs), South West (315), and Pacific Coast (230) regions, and the fewest AADs occurred in Alaska (86) (Figure 2). Age-adjusted AAD rates were highest in the Northern Plains (95.2; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 86.5–103.9), Alaska (92.6; CI = 72.4–112.8), and the South West (80.2; CI = 70.8–89.6), and were approximately four to five times higher than the rate in the East (19.2; CI = 15.8–22.6).

Age-adjusted AAD rates and the relative contributions of AADs to total deaths and total YPLLs were substantially higher for AI/ANs compared with the U.S. general population. The age-adjusted AAD rate per 100,000 for AI/ANs was 55.0 (CI = 52.1–57.9) versus 26.9 (CI = 26.7–27.1) for the U.S. general population. Furthermore, AADs accounted for 11.7% of total deaths among AI/AN versus 3.3% for the U.S. general population, and alcohol-attributable YPLLs accounted for 17.3% of total YPLLs for AI/ANs and 6.3% of total YPLLs for the U.S. general population. The average number of YPLLs per AAD also was higher for AI/ANs compared with the U.S. general population (36.3 years versus 29.9 years, respectively).

Reported by: TS Naimi, MD, Zuni Public Health Svc Hospital; N Cobb, MD, Div of Epidemiology; D Boyd, MDCM, National Trauma Systems, Indian Health Svc. DW Jarman, DVM, Preventive Medicine Residency and Fellowship Program; R Brewer, MD, DE Nelson, MD, J Holt, PhD, Div of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; D Espey, MD, Div of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; P Snesrud, Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities; P Chavez, PhD, EIS Officer, CDC.

Editorial Note:

This is the first national report of AADs and YPLLs among AI/ANs; the results demonstrate that excessive alcohol consumption is a leading cause of preventable death and years of lost life in this population. During 2001–2005, AI/ANs were more than twice as likely to die from alcohol-related causes, compared with the U.S. general population; 11.7% of AI/AN deaths were attributed to alcohol. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies (4,5) and might help account for the high rates of injury-related death (e.g., motor-vehicle traffic crashes) that have been observed in this population. The finding that AAD rates vary by region demonstrates that alcohol does not impact all AI/AN communities to the same extent. AI/ANs in specific regions (e.g., Northern Plains) have lower life expectancies; this is likely attributable, in part, to deaths from alcohol-attributable conditions (6).

To further address alcohol-attributable mortality among AI/ANs will require concerted action by multiple organizations and groups, including AI/AN communities, towns on nonreservation lands within and surrounding AI/AN communities, and national, state, and local health agencies. Bans on the sale and possession of alcoholic beverages on certain Indian reservations have been shown to reduce consumption and related harms (5), although the efficacy of such policies is influenced by access to alcohol in surrounding communities (7). Culturally appropriate clinical interventions for reducing excessive drinking (e.g., screening and counseling for excessive alcohol consumption and treatment for alcohol dependence) should be widely implemented among AI/ANs (7). In addition, tribal court systems, which deal with large numbers of alcohol-related crimes, should be better integrated with the health-care system and substance-abuse treatment programs.

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, some AI/ANs might have been misclassified by race on death certificates, which would underestimate the total number of AI/AN deaths (8). In a 1996 Indian Health Service study, racial misclassification on death certificates of American Indians ranged from 1.2% in Arizona to 28.0% in Oklahoma and 30.4% in California (8). Second, this study did not use race-specific AAFs for most conditions, which might result in AAD underestimates for certain conditions (e.g., homicide and suicide) for which the AAFs are thought to be higher among AI/ANs (4). Third, ARDI does not estimate AADs for several conditions (e.g., tuberculosis, pneumonia, hepatitis C, and colon cancer) for which alcohol is believed to be an important risk factor but for which suitable pooled risk estimates are not available. Finally, bridged-race census estimates used in this report are based on multiple race categories; use of denominators based on other race categorization methods (e.g., 2000 U.S. Census data or tribal census data) would result in higher rates than reported.

Indian Health Service has initiated an alcohol screening and brief counseling intervention program to help reduce excessive alcohol consumption and related harms among AI/ANs in trauma settings. In addition, effective population-based interventions should be implemented to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in AI/AN populations. These include reducing alcohol availability by limiting outlet density, enforcing 21 years as the minimum legal drinking age (9), increasing alcohol excise taxes, and enforcing laws prohibiting sales to underage or already intoxicated persons, particularly in communities bordering reservations (10). Future efforts should explore regional differences in AADs and evaluate other intervention strategies for reducing alcohol-attributable mortality among AI/AN populations.

Acknowledgments

This report is based, in part, on data contributed by T Lindsey, National Center for Statistics and Analysis, National Highway Traffic Safety Admin, US Dept of Transportation; M Zack, Div of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease and Public Health Promotion; and C Rothwell and D Hoyert, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC.

References

1) Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291:1238–45.

2) May AP. The epidemiology of alcohol abuse among American Indians: the mythical and real properties. The IHS Primary Care Provider 1995;20:37–56.

3) Smith GS, Branas CC, Miller TR. Fatal nontraffic injuries involving alcohol: a metaanalysis. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:659–68.

4) May PA, Van Winkle NW, Williams MB, McFeeley PJ, DeBruyn LM, Serna P. Alcohol and suicide death among American Indians of New Mexico: 1980–1998. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2002;32:240–55.

5) Landen MG, Beller M, Funk E, Propst M, Middaugh J, Moolenaar RL. Alcohol-related injury death and alcohol availability in remote Alaska. JAMA 1997;278:1755–8.

6) Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, et al. Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med 2006;3:e260.

7) Guthrie P. Gallup, New Mexico: on the road to recovery. In: Streicker J, ed. Case histories in alcohol policy. San Francisco, CA: Trauma Foundation; 2000.

8) Indian Health Service. Adjusting for miscoding of Indian race on state death certificates. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Indian Health Service; 1996.

9) Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Excessive alcohol consumption. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. Available at http://www.thecommunityguide.org/alcohol/default.htm.

10) Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: no ordinary commodity. A summary of the book. Addiction 2003;98:1343–50.

* Available at http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/ardi.

† Available at http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/ardi/aboutardimethods.htm#aafs.

§ Available at http://www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov/main/index.aspx.

¶ Available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.htm.

** Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss.htm.

Indigenous Resistance, 1960s-Present

Since the invasion of our territories began in 1492 our people have had to mobilize to defend our sovereignty. Indigenous Resistance has taken on many forms, and has revealed itself through the Pontiac Rebellion, Battle of Little Bighorn,The Ghost Dance, Riel Rebellion, American Indian Movement, Oka Crisis, the Zapitista Movement, Native Youth Movement etc.

However, when most settlers think back to the conquest of the territory that now makes the United States and Canada, most of them think that the end of the so-called “Indian Wars” as the cap of it, officially happening sometime around 1890. In that year some 300 unarmed Lakota men, women & children were massacred at Wounded Knee, South Dakota by the armed forces of the United States.

From this period until the 1950s, Native peoples were largely pacified & controlled by the colonial settler states. Native children were stolen from their families and thrown in schools in an act of genocide. Their cultures, languages and spiritual practices were annihilated by the white supremacist schooling in an effort to, by any and all means, assimilate Natives into white settler society.

Resistance by our people, and militant police action by the colonial state to suppress our resistance, did continue though. In 1924 Canada violently suppressed the traditional government of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, one of the few remaining traditional Native governments in the wake of the Indian Act.

For the most part however the protests of Natives consisted of lobbying the government for better treatment. In the 1950s things began to change. Largely inspired by the Black Civil Rights struggle in the U.S., Natives in both Canada and the U.S. also began organizing. In the south west, Native students began organizing, while in the Northwest, coastal Natives began asserting their treaty rights to fish. The Prairies and the Kanien’kehaka, or Mohawks, of Québec, Ontario and the U.S. lead the charge in this new militancy.

This movement was the first to occur outside the official sactioned band & tribal council system set up by both U.S. & Canadian governments (Native compradors). This early movement established a the basis for a grassroots network of conscious Natives opposed to colonization, and who were committed to maintaining their traditional culture & values, much of which had been lost in the forced schooling of Native children. This informal network formed the basis for the next phase of resistance which took off in the 1960s.

Its no historical mystery that the 1960s was a period marked by rebellion and a revolution on a global scale. Taking inspiration from the fierce resistance of the Vietnamese people against U.S. invasion & occupation, the Cultural Revolution in People’s China and the widespread revolt of students and workers in Europe, new social movements emerged, including the Black Panthers, and the women’s, students, queer liberation and anti-war movement.

It is from this period that the current Native resistance movement more or less emerged. In the 1980s things began to quiet down, but then Oka in 1990 exploded, reviving the movement for the last 20 years. This last 35-year period therefore forms an important part of our history as a movement.

A Timeline of Brown and Red Native Unity

I am of the firm belief that Chicanos/Mexicanos, who are a people representing both full blooded Natives as well as people of mixed Native and European, as well as African, descent should be rightly seen as Native people to North America alongside Indians, Metis and Inuit. They have had their cultures, their languages and their histories twice assaulted: first by the Spanish invaders of Mexico and the American south west, and second by the U.S. gringos following the seizure of northern Mexico. Many have lost their once organic relationship to their indigenous past, but their have always been pockets of resistance, and remembrance. During the height of the Red Power and Chicano Power movements there were many examples of powerful working relationships between brown and red Natives, and today that relationship continues on.

It is not the various names, logo’s, flags, patches, initiation ceremonies or individual groups we organize under that defines us. These things are not important. It is the institution of Indigenous Resistance that unifies us, brown and red, all into one Movement. In recognition of this I have included on this time line not just those actions and events by people called Native by the colonial state, but also those of our brown brothers and sisters.

Mexica Tiahui! Hoka Key!

1954

The U.S. Congress passed the Menominee Termination Act, ending the special relationship between the Menominee tribe of Wisconsin and the federal government. Following the termination of the Menominee the Klamath tribe in Oregon was terminated under the Klamath Termination Act. Finally The Western Oregon Indian Termination Act was enacted west of the cascade mountains. This termination was unique because of the number of tribes it affected. In all, 61 tribes in western Oregon were terminated. This total of tribes numbered more than the total of those terminated under all other individual acts.

1958

The U.S. Congress passed the California Rancheria Termination Act. Rancherias are unique Californian institutions referring to Indian settlements established by the U.S. government. The act terminates 41 of these settlements.

1964

An amendment to the California Rancheria Termination Act was enacted, terminating additional rancheria lands.

1967

The first Brown Beret unit is organized in December in East Los Angeles, California.

1968

At Kahnawake (ga-na-WAH-gay), a traditional Kanien’kehaka Singing Society is formed, which would later become the Mohawk Warrior Society. They begin to take part in protests & re-occupations of land. As well, a protest & blockade of the Seaway International Bridge (demanding recognition of Jay Treaty), at Akwesasne, ends with police attack & arrests of scores of Mohawks.

The American Indian Movement, a Warrior Society of urban Indians, is formed in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Inspired by the traditional Warrior Societies of nations like the Mohawk, and taking cues from the serve the people programmes of the Black Panthers, AIM establishes a community centre, and provides help to Indians in finding work, housing and legal aid. It also helps to organize early protests, and establishes a copwatch patrol. Although the most well known, AIM was just one part of a broad Native resistance movement that emerged at this time (sometimes referred to as Red Power). Other important groups to emerge out of this period are United Native Americans and United American Indians of New England.

The Brown Berets organized chapters throughout the states of California, Arizona, Texas, Colorado, New Mexico and as far away as Milwaukee, Chicago, Detroit, Minnesota, Ohio, Oregon, and Indiana, becoming a national organization.

1969

The event that really kicked things off for the Red Power Movement, the occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. The occupation was largely in response to the U.S. Federal Government’s policy of Termination, which eliminated tribal status. The two guinea pigs for the policy, the Menominee of Wisconsin and the Klamath of Oregon, suffered terrible social and economic consequences. The action would last 19 months and be the first Indian protest to receive national & international media coverage. Thousands of Indians participated in the action, most coming from urban areas and searching for their identity.

In March, in Denver, Colorado the Crusade for Justice, a Chicano organization, organized the first National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference that drafted the basic premises for the Chicana/Chicano Movement in El Plan de Aztlán. The following month over 100 Chicanas/Chicanos came together at University of California, Santa Barbara to formulate a plan for higher education: El Plan de Santa Barbara. With this document they were successful in the development of two very important contributions to the Chicano Movement: Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA) and Chicano Studies.

1970

AIM protests disrupt the re-enactment of Mayflower landing at Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts, gains national attention & helps AIM to expand. United American Indians of New England declared US Thanksgiving Day a National Day of Mourning. It becomes an annual protest.

The San Diego Brown Berets occupy the land that was to be a California Highway Patrol station in LoganHeights under the Coronado Bridge, forming Chicano Park.

1971

In Pennsylvania, unknown persons break into FBI office and take many classified documents. These revealed the existence of the Bureau’s Counter-Intelligence Program. COINTELPRO, as it was known, set up surveillance and organized repression against progressive social movements in U.S. The program initially targeted the African Liberation Movement, especially the Black Panthers, but would later also turn its eyes on the Red Power and Chicano Movements. It used imprisonment, assaults and lethal force to enforce the established order.

The Brown Berets marched one thousand miles from Calexico to Sacramento in “La Marcha de laReconquista” to protest statewide against racial and institutionalized discrimination, police brutality, andthe high number of Chicano casualties in Vietnam. The Brown Berets then embarc on a yearlong nationwide expedition in “La Caravana de la Reconquista” toorganize La Raza on a national scale to secure rights and self-determination for La Raza.

After much struggle by both the Chicano and the Indian communities (though not without some disagreement), D–Q University is founded. The two year college is path breaking in the way it openly treats Chicanos as tribal Native people. The school becomes home to members of the American Indian Movement, as well as a meeting place for MEChA.

1972

AIM and many other native groups organize the Trail of Broken Treaties. The TBT is a caravan that travelled from the west coast to Washington, D.C. When the caravan of several thousand activists arrived in Washington, government officials refused to meet with them. In response The Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters is occupied for 6 days. Extensive damage is done to the property and thousands of files taken.

In February of that year Raymond Yellow Thunder is killed by settlers in Gordon, Nebraska. His murderers are only charged with manslaughter, and were then released without bail. AIM organized several days of protests and boycotts, and succeeded in having actual murder charges laid against the settlers. The police chief fired. Yellow Thunder is from Pine Ridge, and this incident helps build a stronger relationship between AIM and traditional Lakotas on the reserve.

The Brown Berets reclaimed Isla de Santa Catalina in order to bring attention of the illegal occupation of theislands by the U.S. and to claim it on behalf of the Chicano people and to bring attention to the shortage ofhousing for the Chicano community. The U.S. has illegally occupied this and the other Archipelago Islandsknown as the Channel Islands since 1848 when they signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Brown Berets were infiltrated by sellouts and subversives working for outside organizations including butnot limited to the FBI, LAPD, CWP, ATF, and other “law enforcement” agencies and organizations workingto co-opt the Movimiento Chicano to serve their own agendas. The Brown Berets were disbanded by thethen Prime Minister David Sanchez in order to circumvent any violence the members of the organizationwhich was being promoted by those infiltrators mentioned above.

1973

Another Indian, Wesley Bad Heart Bull, is killed by another racist settler, this time in South Dakota. Again the perpetrator is only charged with manslaughter. On February 6, an AIM again protests against this kind of injustice. In Custer, SD, the protests cause the courthouse erupts into riot. Police cars and buildings are set on fire. 30 people arrested.

On the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, large numbers of police and US Marshals are deployed to counter the activities of AIM and traditionalist Lakotas opposed to the corrupt tribal president Dick Wilson. With the aid of U.S. government funing Wilson established a paramilitary force known as the Guardians of the Oglala Nation, called GOONs by AIM and its allies.

In a period beginning in this year and ending in 1976, some 69 members or associates of AIM were killed by the GOONs, BIA police and FBI agents in and around Pine Ridge.

Angered by the ongoing repression and violence, some 200 AIM memebers, supporters and traditionalist Lakota warriors begin an occupation of Wounded Knee on February 27. The government responds with a 71-day siege during which two Natives were shot and killed (Buddy Lamont & Frank Clearwater). The siege ends on May 9.

At Kahnawake in September, the Mohawk Warrior Society evicts non-Natives from the over-crowded reserve. This leads to armed confrontation with Québec police in October. Warriors begin to search for land to re-possess.

1974

A group of traditionalist Mohawks, along with veterans of the Wounded Knee occupation, begin an occupation of Ganienkeh in New York state. The warriors retake land and engage in an armed standoff with state police. Eventually, negotiations result in Mohawks taking a parcel of land in upstate NY (in 1977). Ganienkeh, a community run in accordance with ancient Six Nations tradition, continues to exist today.

In Canada, the Native People’s Caravan, modelled after Trail of Broken Treaties takes place form September 14 to 30, and heads from Vancouver, British Colombia to Ottawa. It ends with riot police attacking 1,000 Indian activists at Parliament Building.

Armed roadblocks and occupations occur at Cache Creek, British Colombia, and Kenora, Ontario.

1975

Perhaps the most famous incident of the period: the shootout at Oglala. At Oglala, on the Pine Ridge reservation, the FBI botched a raid on an AIM camp. The failed operation ends with 2 agents killed along with 1 Native defender (Joe Stuntz-Killsright). The FBI launched one of the largest man hunts in US history for AIM suspects afterwords.

Elsewhere, in Wisconsin, the Menominee Warrior Society occupied the abandoned Alexian Brothers novitiate building in Gresham, Wisconsin. The occupation lasted thirty four days and, when it ended, many leaders of the occupation faced criminal indictments and trials.

1976

In February, the body of Anna Mae Pictou-Aquash, a Mik’maq from Nova Scotia, Canada, and member of AIM, is found on the Pine Ridge reservation. Aquash was one of the most well known female members of AIM, a veteran of the BIA occupation and Wounded Knee. Despite an initial cover-up by the FBI, an independent autopsy finds that Aquash had been executed with a bullet in the back of the head. The FBI or GOONs are primary suspects. To this day no one knows for sure who killed Anna Mae, and her death has been used to tear the movement apart, with some fingering others within AIM, and others the government.

Two suspects in the FBI deaths at Oglala (Dino Butler & Bob Robideau) are found not guilty on grounds of self-defense. A third suspect, Leonard Peltier, is captured in Canada. Using false evidence, the FBI have Peltier illegally extradited to South Dakota.

1977

The trial of Leonard Peltier ends with his conviction of murder and imprisonment for 2 life terms. His conviction is based on FBI fabrication and withholding of evidence. Peltier remains in prison to this day, one of the longest held Prisoners of War in the U.S.

1981

On June 11, some 550 Québec Provincial Police raid Restigouche, a Mik’maq reserve of 1,700. Riot police carry out assaults and search homes for evidence of ‘illegal’ fishing. This is in response to complaints by white fishermen that the Mi’kmaq take more than their fair share of fish. This is despite the fact that the white fishermen take order of magnitude more fish than the Indians.

Unión del Barrio is formed. UdB is a Marxist-Leninist and revolutionary nationalist organization Raza organization. UdB expands the usual definition of La Raza to include the indigenous people of North America, making Brown and Red native unity part of its program.

1988

Over 200 Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), including riot & Emergency Response Teams, raided the Mohawk territory of Kahnawake. They claimed they are searching for illegal cigarettes. In response Warriors seized the Mercier Bridge, a vital commuter link into Montreal, part of which runs through the Kahnawake reserve.

In northern Alberta, the Lubicon Cree began road-blocks against logging and oil companies devastating their territory & way of life. A logging camp and vehicles are damaged by Molotov attacks. The struggle of the Lubicon continues to this day, now with the added threat of even greater ecological destruction and health effects at the hands of the Canadian Oil Sands.

In Labrador, Innu activists began protesting NATO fighter-bomber training at a Canadian military base. Many Innu were arrested during the blockade of runways.

1990

The Oka Crisis. Over 100 heavily-armed Québec provincial police raided a Mohawk blockade at Kanesatake/Oka on June 11. In an initial fire-fight, one cop is shot & killed. Following a 77-day armed standoff began. Eventually it came to involve 2,000 police and 4,500 Canadian soldiers, deployed against both Kanesatake & Kahnawake. The Oka Crisis inspired solidarity actions across country, including road and rail blockades and sabotage of bridges and electrical pylons.

1992

During protests against the 500-year anniversary of Columbus’ invasion of the Americas in October, dozens were arrested in Denver, Colorado. In San Francisco, riot cops fought running battles with protesters, who set 1 police car on fire and disrupted an official Columbus Day parade and re-enactment of his landing.

1993

Brown Berets are re-activated under the old Charter and Provisions as laid out by the previous BrownBeret National Organization.

1994

The Zapatista Rebellion begins. In Chiapas, Mexico, armed rebels of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation launched their New Year’s Day offensive, capturing 6 towns and cities. Comprised of Indigenous peoples, the EZLN declare war on the Mexican state and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In response, the government deployed 15,000 soldiers and killed several hundred civilians in attacks. Since 1994, the Zapatistas have continued to gain widespread support and sympathy throughout Mexico and the world. Along with Oka, the Zapatista uprising helps to inspire and drive 20 years of resurgence in the Indian movement in North America.

1995

Two major events took place this year in Canada. The first is in Ipperwash, Ontario, were an unarmed protest and re-occupation ended with Ontario police opening fire on the protesters. They kill one Indian, Dudley George, on September 6. The re-occupation had begun in 1993. The land, originally the Stoney Point reserve, was taken by the government during the second world war for use as a temporary army base. After the killing of Dudley George, the government admitted the peoples claims were justified. The second incident is the month-long siege that occured at Gustafsen Lake in the south-central Interior of British Colombia. It began after a settler attempted to evict Secwepemc sundancers from their traditional ceremonial grounds. Some 450 heavily-armed RCMP ERT, with armoured personnel carriers from the Canadian military, surround the rebel camp.

1997

The Native Youth Movement, a militant grouping of largely urban Indians inspired by the original AIM, founded a chapter in Vancouver, British Colombia. It was inspired by the year-long trial of Gustafsen Lake defenders, held near Vancouver. NYM soon began attending conferences, organizing protests, distributing information, etc. In April, NYM carried out 2-day occupation of BC Treaty Commission offices.

1998

The NYM branch in Vancouver carried out 5-day occupation of BCTC offices in April, and a 2-day occupation of Westbank band offices in Okanagan territory. Both of these are actions against treaty process.

1999

The NYM branch in Vancouver helped members of Cheam band, located near Chilliwack British Colombia, assert their right to fish on the Fraser River. NYM Warriors wear masks and camouflage uniforms. They also carry batons to deter Fisheries officers, who routinely harassed Cheam fishers. As a result of this the NYM forms security force. This later took on a life of its on and became the Westcoast Warrior Society.

2000

In May, members of the St’at’imc nation established Sutikalh camp near Mt. Currie, British Colombia, to stop a massive ski resort from being built on an untouched alpine mountain area.

At Burnt Church, New Brunswick, Mi’kmaq fishermen again attempted to assert their treaty rights to fish lobster in September & October. They were again met with repression from hundreds of police and fisheries officers. Members of Westcoast Warrior Society participated in defensive operations.

In October, Secwepemc established the first Skwelkwekwelt Protection Center to stop expansion of Sun Peaks ski resort, near Kamloops, British Colombia. Over the years, some 70 people are arrested and charged as a result of protests, roadblocks & re-occupation camps.

After decades of the struggle by the Indian community and its allies, the San Francisco Peaks are designated a Traditional Cultural Property, which allows it to be eligible for consideration as an official National Historic Register site.

2001

In May, a Secwepemc NYM chapter was established. A 2-day occupation of government office in Kamloops occured to protest selling of Native land.

In July, over 60 RCMP with ERT raided Sutikalh after a 10-day blockade of all commercial trucking on Highway 97. Seven persons are arrested.

2002

In December, Annishinabe in the northern Ontario community of Grassy Narrows began to blockade logging companies from destroying their traditional territory. The blockade becomes one of the longest in recent history, continuing through to the present, and directed primarily against Weyerhaeuser and Abitibi corporations.

In September, RCMP, including Emergency Response Teams and Integrated National Security Enforcement Team (INSET), raided the homes of West Coast Warrior Society members on Vancouver Island. They were allegedly searching for weapons.

2003

In April, homes of NYM members were again raided, this time in Bella Coola and Neskonlith, by RCMP including ERT. This time the cops took computers, address books & propaganda.

2004

In January, Mohawk warriors surrounded the Kanesatake police station after band chief brings in outside police forces to crackdown on political opposition. Over 60 police were barricaded inside station. Chief’s house and car are burned.

In June, RCMP INSET, along with Vancouver police ERT, arrested members of West Coast Warriors Society, for making legal purchase of firearms. Rifles and ammunition were seized in the bust. Shortly after, the West Coast Warrior Society was disbanded by its members. They cited the ongoing repression of them by the police.

2005

In January, members of the Tahltan in northern ‘British Columbia’ occupied the band office in Telegraph Creek in opposition to band’s involvement with mining and oil & gas corporations. In July they began blockading roads being used by construction machinery, and in September fifteen Tahltans including elders were arrested by the RCMP. The Tahltan continued their campaign, including blockades, through 2006 and 2007.

2006

On April 20, over 150 Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) attempted to forcibly remove a blockade at the Six Nations reserve territory near Caledonia, in southern Ontario. They violently arrest 16 Indians, using physical assaults, pepper spray & tasers. The Ontario Provincial Police are forced to withdraw however, as hundreds of Six Nations members converge on the site. More blockades were erected in the area, including on Highway 6, which consisted of burning tires, vehicles and dismantled electrical pylons, and mounds of gravel. A train bridge was also burned down. The next day on the Tyendinaga reserve, a Canadian National Railway line was blocked, cutting off a major freight and passenger line. The Six Nations members originally began their blockade to stop a housing development on land they claimed belongs to them. The blockades and land reclamation continue for over a year, with numerous conflicts with settlers and police occurring, as well as sabotage.

In July, Grassy Narrows Annishinabe protesters, along with members of the Rainforest action Network, blockaded the Trans-Canada Highway. Several persons were arrested.

In July, Grassy Narrows Annishinabe protesters, along with members of the Rainforest action Network, blockaded the Trans-Canada Highway. Several persons were arrested.

This year also saw the founding the Wasasé Movement. Wasáse said about itself that it was “an intellectual and political movement whose ideology is rooted in sacred wisdom. It is motivated and guided by indigenous spiritual and ethical teachings, and dedicated to the transformation of indigenous people in the midst of the severe decline of our nations and the crises threatening our existence. It exists to enable indigenous people to live authentic, free and healthy lives in our homelands.” It is largely based on the thought and strategies for change laid in the book of the same name by University of Victoria professor Taiaiake Alfred, a Mohawk from Kahnawake. They are quite Gandhian in their outlook and approach, and due to its academic orientation, many warriors & grassroots organizers remained unexposed to the movement’s philosophy. The movement only last a few years before self-dissolving.

2007

On March 6, a massive Olympic flag that was being flown at the Vancouver City Hall was stolen just as a delegation from the International Olympic Committee arrived to inspect the city’s preparations for the 2010 Winter Olympics. A few days later, as the IOC tour ended, the Native Warrior Society released a communiqué claiming responsibility for taking the flag, including a photograph of three masked members standing in front of the Olympic flag and holding a Warrior flag. The group claimed the action in honour of Harriet Nahanee, a Native elder who passed away after being sentenced to two weeks imprisonment for taking part in a 2006 blockade of construction on the Sea-to-Sky highway in preparation for 2010.

This year also saw the attempt by a group of Lakota leaders to move for the unilateral withdrawal of the Lakota from the Treaties of 1851 and 1868 as permitted under the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, of which, the United States is a signatory. Their proposed independent nation is called the Republic of Lakotah.

On the June 29 a Day of Action was called by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), the the national organization of the Indian Act band council chiefs across Canada. The AFN claimed the event as a huge success , with over 100,000 people participating, however most of the people participating in the actions, protests, and rallies were non-native, which speaks to the AFN’s inability to mobilize their people despite all the resources they have. In fact, many militant Native organizations, such as the Native Youth Movement, called a boycott of the Day of Action. These organizations, rightly, stated that the AFN does not represent our people and that, when they talk about solutions, their long-term goal is actually assimilation.

In December members of the Chaco Rio Indian community in New Mexico established a blockade to prevent preliminary work for proposed development of a massive coal-fired power plant.

2008

Across Canada the so-called Olympic “Spirit Train” was met with disruptions and protests at its stops by Native warriors and their non-Native allies. Across Canada other preparations for the 2010 Winter Olympics, set to take place on unceded Indian land, were disrupted by protesters.

The Mohawk Nation branch of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy at Kahnawake filed a formal complaint about the construction of Super Highway 30.

2009

The land reclamation effort at Caledonia by the Six Nations Haudenosaunee Confederacy entered its third year with the warriors showing no signs of backing down. It continues to be ongoing to this day.

Warriors of the Mohawk Nation branch of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy at Akwesasne – which straddles Ontario, Québec and New York State – expelled Canadian border guards at a crossing with the United States which passes through their territory, seizing control of the border station.

Native warrior, American Indian Movement leader and political prisoner Leonard Peltier is again denied parole by the colonial government in the United States. His next parol hearing will not be until the year 2024.

2010

In February Native warriors gathered with anti-capitalists/anti-imperialists, feminists, environmentalists and other social justice advocates to fight back against the Vancouver Winter Olympics which took place on unceded Coast Salish territory.

In July people in Oka and the nearby Mohawk community gathered to remember the resistance at Oka and to protest the ongoing attempts to marginalize the Mohawk people and take their land.

The Canadian Federal Government used an obscure part of the 1900 Indian Act to forcibly strip the Barrie Lake Algonquin of their traditional government, and replace it with a Band Council subservient to Ottawa. The Barrie Lake people met this imperialist-colonialist move with stiff resistance.

John Graham, a Native of the Yukon, and a former member of the American Indian Movement, is convicted of the murder of his former AIM comrade Anna Mae Pictou Aquash. As noted earlier, much of the evidence in the case points to Anna Mae’s death having been at the hands of the FBI.

2011

In June 500 agents of the colonial state invade sovereign Mohawk communities in Quebec. On paper they are looking for marijuana, but it much more likely that this is state terror tactics against some of the most firmly sovereigntist Native communities on the continent.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS