Views: 2657

‘Radni logor Jasenovac’ (‘Jasenovac Labour Camp’), the latest work by Croatian author Igor Vukic on the Croatian World War II concentration camp Jasenovac, published by Naklada Pavicic this year, seems like it is inspired by the publications of established Holocaust deniers.

Instead of studying all the available archival records, testimonies and other publications, Vukic avoids confronting the totality of known information on the Jasenovac concentration camp system, and instead cherry-picks and publishes only carefully selected data which supports his ideologically-motivated agenda – the fabrication that Jasenovac was merely a labour camp where no mass murders took place.

Instead of studying all the available archival records, testimonies and other publications, Vukic avoids confronting the totality of known information on the Jasenovac concentration camp system, and instead cherry-picks and publishes only carefully selected data which supports his ideologically-motivated agenda – the fabrication that Jasenovac was merely a labour camp where no mass murders took place.

The argumentation and evidence cited by Vukic – who is not a history academic and has no degree or PhD in the field – is incomplete, distorted, and occasionally completely wrong.

The footnoted sources are often lacking important data which makes corroboration of his writing very difficult, if not impossible.

It is no coincidence that there are no peer reviews of Vukic’s book by established scholars as is usually the case with historical works.

However, the author goes to much trouble to give this book an appearance of a scholarly, organised and thoroughly-researched work. This is consistent with the practice of denial and distortion in the West – avoiding a scrupulous and detailed investigation, while creating an illusion of it in order to promote unsupported, dubious and often false claims.

The first clue showing that Vukic’s work is not up to the historiographical standard that any objective scholar can recognise is his inability to present the sources of quoted data in an organised and systematic fashion.

This problem obviously originates from the fact that Vukic’s recent book borrows heavily from his earlier text, ‘Sabirni i radni logor Jasenovac 1941.-1945’ (‘Jasenovac Collection and Labour Camp 1941-1945’), published on pages 55-134 of the book ‘Jasenovački logori – istraživanja’ (‘Jasenovac Camps – Research’), authored by Vladimir Horvat, Stipo Pilic, Blanka Matkovic and Vukic himself.

In 2015, when that book was published, Vukic systematically failed to quote from archival sources correctly, usually mentioning only the archival collection signature accompanied by either box or microfilm number.

Since archival collections are occasionally reorganised by archivists, usually in cases when additional documents are found or made available, box numbers are not permanently fixed, and the contents of a specific numbered box can change with time. It is therefore essential for a historian to fully quote document registry numbers or even dates of issue to ensure the verifiability of such data.

Vukic’s handling of this problem has improved with time, and in his latest book, when quoting archival documents, he sometimes uses a complete signature for quoted documents, but at the same time, he failed to correct most of the footnotes that were reused from his earlier text. This could be a sign of omission, but at the same time, it could also be a tactic used by the author in order to make attempts to refute his claims more difficult.

This is especially problematic when Vukic tries to quote from microfilmed documents. One roll of such microfilm can contain over 1,000 individual pages, but Vukic very rarely annotates exact page numbers.

In this way, he ensures that anyone who wishes to check his quotes must spend an excruciating amount of time to do it, making fact-checking of his book almost an impossible mission. It is debatable whether this a deliberate choice or a potential sign of scholarly incompetence.

Theproblems with correctly quoting sources in this book become obvious when one tries to fact-check some of his claims. It would take too much space to annotate all such instances, but a handful of examples can be used to show his modus operandi.

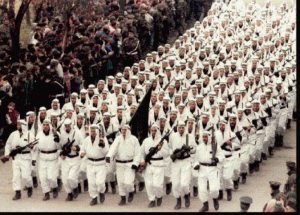

Jasenovac death camp: Croatian soldiers are killing the Serb prisoner

Jasenovac death camp: Croatian soldiers are killing the Serb prisoner

For instance, Vukic occasionally quotes from the memoirs of Ante Ciliga, who was taken to Jasenovac concentration camp in 1942, but later released. Vukic is clearly unable to correctly annotate which edition of Ciliga’s work he used – in the bibliography, he claims to have used the edition published in Rome in 1978, but in the footnotes, he repeatedly lists another collection of Ciliga’s texts edited by Branimir Donat and reissued in Zagreb in 2001.

Having made the corroboration of the authenticity of Ciliga’s words much more difficult, Vukic does not stop, but actually even distorts, obfuscates and (deliberately or not) falsifies Ciliga’s writings.

When describing the punishment of Bruno Diamantstein and other prisoners designated as camp functionaries, who were caught stealing valuables taken from other inmates and selling them outside the camp in cooperation with some of the Ustasa guards, Vukic claims that there were other similar cases in which Jasenovac inmates were punished together with the guards.

While not mentioning the correct page on which Ciliga describes this, Vukic writes that Ciliga mentioned a case in which two inmates were shot dead together with two guards, with whom they had organised a network that was stealing textiles produced in the camp and selling them outside Jasenovac.

Even though, in his memoirs, Ciliga described two such cases that he personally witnessed, both the execution of Diamantstein group and the execution of textile-smuggling inmates together with the Ustasa found helping them, Vukic incorrectly claims that Ciliga witnessed only the second execution.

He even states that this was the only murder that Ciliga saw with his own eyes while being held at Jasenovac, neglecting to mention Ciliga’s claim that he watched the mass murder of Roma prisoners who were caught preparing an escape attempt in Camp IIIC.

Jasenovac functioned as a system of camps – Camp III, next to the village of Jasenovac, operated as the main camp from November 1941. An important sub-camp was based in a former prison in nearby Stara Gradiska, while many people selected for execution were transported from the main camp across the river Sava to Donja Gradina, which operated as a killing field/site.

Ciliga mentions numerous other mass murders committed by Ustasa outside the main camp, usually in Donja Gradina.

Of course, Ciliga was not able to see with his own eyes what was happening there, since only a handful of inmates were lucky enough to survive Donja Gradina.

However, Vukic systematically omits every such claim as if it never happened, not only from Ciliga’s memoirs but from every other survivor’s testimony.

In addition to survivors, many Ustasa guards who were interrogated after the end of the war corroborated the information that Donja Gradina was used as a killing site, where the greatest number of Jasenovac victims were murdered.

Vukic does not even try to explain why he believes these witnesses are not trustworthy – he simply ignores every such testimony since he cannot explain them or to incorporate them into his deeply flawed narrative. In some cases, he even incorrectly cites the known data regarding the duration of imprisonment of some Jasenovac inmates, in order to make them and their testimonies about mass murders in Jasenovac less credible.

For example, Vukic incorrectly claims that Djordje Milisa “spent his year of imprisonment in Stara Gradiska” sub-camp and that Milisa, therefore, cannot be considered a valid witness about the situation in the main camp at Jasenovac brickworks. However, Vukic conveniently ignores the fact that Milisa arrived at the Jasenovac main camp in early December 1941, where he remained until January 7, 1942.

He completely ignores the 33 days Milisa spent in the main camp, where he could personally see many of the horrors described in his memoirs. Vukic also incorrectly claims that Milisa spent only one year in the concentration camp, while he actually spent double that time in the main Jasenovac camp and at Stara Gradiska, not counting the time he spent in various prisons before being sent to the concentration camp.

When describing the process of transporting new inmates to Jasenovac, Vukic uses a similar method in order to distort the tragedy of Jasenovac. He quotes some documents while ignoring others to strengthen his claim that most of the Jasenovac inmates were not captured based on their racial or national identity, but rather based on the fact they actively resisted the Ustasa state.

Vukic claims that according to the surviving archival records of the Ustasa police for the city of Zagreb and the surrounding county, only approximately 1,000 inmates were sent to Jasenovac from that area from March to December 1942. He adds that the largest of these groups consisted of no more than 50-60 people and that the majority of them were Catholic Croats, supporters of the Communist-led resistance against the Ustasa.

However, Vukic does not feel the need to explain to his readers that the surviving records are not complete and that only a small percentage of the original documentation survived the Ustasa retreat in 1945 intact.

Jasenovac death camp: Croatian soldiers are celebrating the killing of the prisoners by knives

Jasenovac death camp: Croatian soldiers are celebrating the killing of the prisoners by knives

Also, Vukic ignores documents which clearly show that there were other deportations from that same area, based purely on racial motivation.

On June 10, 1942, the Directorate for Public Order and Security reported to the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Independent State of Croatia that it received a report regarding the number of Roma sent to Jasenovac and the Stara Gradiška subcamp. From this document alone, one can learn that by that date, the Ustasa had deported 241 male Roma and 620 females with young children from the Zagreb area to Jasenovac and its sub-camps.

This document clearly demonstrates the falsehood of Vukic’s claims – not only is he minimising the number of people sent to the Jasenovac camp system, but he also wrongly portrays the motivation for their deportation.

In this way, he hopes to deny the fact that most of the inmates imprisoned or murdered at Jasenovac were not guilty of any action against the state or the regime, but were rather singled out based on their racial or ethnic identity, in accordance with the racist ideology promoted by the Ustasa.

These inconvenient details are conveniently ignored by Vukic because they would completely shatter his distorted description of Jasenovac and would obliterate his attempts to deny the genocidal nature of mass murder committed by the Ustasa in Jasenovac, not only against Jews, but also against Roma and Serbs.

One could mention many other mistakes, falsehoods and fallacies found in Vukic’s book. It is an inconsistent, distorted and deeply flawed description of the Jasenovac concentration camp system.

Vukic does not even comprehend that the Jasenovac main camp cannot be discussed or analysed in isolation from other sub-camps like Stara Gradiska, or without dealing with the full extent of Ustasa ideology and the system of terror that was fuelled by it.

The data and argumentation used by Vukic aren’t meant to describe the totality of what Jasenovac really was, or what it meant for many of its victims to be deported to such a foul place, but rather aim to create an appearance of scholarly seriousness while lacking all its defining elements.

Vukic did not write this book in order to bring clarity and honesty to the history of Jasenovac, but rather to provide a cloak of veracity and authenticity to what critics have alleged are anti-Semitic and (more importantly in this case) anti-Serbian theories which have clearly and undoubtedly been proven wrong by renowned scholars but are still being propagated by right-wing circles in Croatia.

They, together with Vukic and his associates, are attempting to whitewash the history of the Ustasa-led Independent State of Croatia, either by denying or by distorting the reality of the mass violence used by the Ustasa at Jasenovac and other killing sites.

To achieve their aim, they feel the need to disprove known facts regarding Jasenovac camp, just as Western Holocaust deniers do about Auschwitz.

In order to undermine the existing historiographic consensus about the tragedy of Jasenovac, Vukic has to create a false narrative in which Jasenovac is not a killing site, but merely a labour camp; a place where numerous inmates were not imprisoned because of their race or ethnicity, but because of their alleged active resistance to the state and the government; a setting in which the captives were not brutally murdered in mass killings, but rather died of sickness, while attempting to escape or being bombed to death by the Allied air forces; a place where the Ustasa interned the Jews not to plunder, starve, exploit and finally murder them, but rather in order to spare them from Nazi-organised deportations to Auschwitz.

Jasenovac death camp: A group memory photo with the victims

Jasenovac death camp: A group memory photo with the victims

The fact that this book was actively promoted on the public Croatian Radio-Television, HRT, and was recently endorsed by Milan Ivkosic in Vecernji list, one of the leading Croatian daily newspapers, as a “huge contribution to the search for truth on Jasenovac”, clearly shows the arrogance and brazenness of Vukic and his associates.

It is worth noting that in December 2017, the Croatian War Veterans’ Ministry granted 6,600 euros to the Society for Research of the Threefold Jasenovac Camp, the association at which Vukic conducts his research, for research into Jasenovac.

It is therefore of critical importance not to ignore Vukic’s book and similar texts but to openly criticise them and publicly stand up against their distortions and denials.

Dr. Franjo Tudjman was in the 1990s President of Croatia

Dr. Franjo Tudjman was in the 1990s President of Croatia

Originally published on 2018-09-04

About the author: Goran Hutinec is an assistant professor at the history department of the Faculty for Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Zagreb.

Source: Balkan Insight

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS