Views: 2509

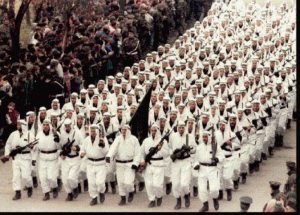

Neo-Nazi Ustashi in Zagreb today

Neo-Nazi Ustashi in Zagreb today

Last week was marked by the moral acrobatics of two Croatian ministers – War Veterans’ Minister Tomo Medved and Defence Minister Damir Krsticevic – who publicly endorsed two convicted Croatian war criminals, Tomislav Mercep and Mirko Norac.

A WWII Independent State of Croatia in which 700.000 Serbs were brutally killed

A WWII Independent State of Croatia in which 700.000 Serbs were brutally killed

Croatian news site Index reported last week that Mercep, who is serving a prison sentence, spent a total of 45 days at a spa instead of in jail this year and last year. As Mercep is a Croatian war veteran, Medved said he vouched for him as worthy recipient of the spa treatment, “as I regularly do” when war veterans are serving prison time for war crimes.

“Croatia has its Homeland War [term officially used in Croatia for the 1990s war] as the foundation of a modern Croatian state, has its Croatian defenders [war veterans], of whom we are proud,” Krsticevic added, reminding reporters that the war and its veterans are sacrosanct here in Croatia.

A few days earlier, while marking the 25th anniversary of the successful Medak Pocket military operation in the Lika region, Krsticevic issued a special greeting to Norac, who was present at the ceremony in the town of Gospic.

“We have to be proud of the Medak Pocket action, as far as Mirko Norac is concerned, it was war, he was the commander of the Gospic headquarters zone, and because of what happened here, he carries his cross. I’m glad he’s here with us today,” Krsticevic said.

It is not clear when Krsticevic referred to Norac’s ‘cross’ if he was implying that Norac was innocent of the crimes or simply suggesting it was tough that he had to serve a sentence.

Medved, who publicly welcomed Norac during this year’s official ceremony to mark the anniversary of the 1995 military operation ‘Storm’, defended Krsticevic, reminding reporters of the merits of war veterans and of Norac.

“He has served his sentence, but let’s not neglect the contribution he has made. Everyone should be honoured and respected for what he did in defence of the homeland… All who have contributed to defending the homeland have their place in history,” Medved said.

While both Mercep and Norac are without doubt war veterans, their potential merits should be seen in the light of the deaths they ordered or failed to prevent.

A war criminal Tomislav Merčep

A war criminal Tomislav Merčep

A girl in pink pyjamas

“The girl came out through the door; her hands were tied. However, snow was falling so she started to slip on the snowy ground. I picked her up in my arms and carried her… Someone told me to cover her eyes; I took a piece of linen that hung over her neck…

“After that, I turned around, and I didn’t want to watch. Then I heard multiple shots. When I turned again, I saw in Munib [Suljic’s] hand a Heckler [& Koch automatic rifle],” Sinisa Rimac, a member of a Croatian reserve police unit, told police investigators in December 1991.

Rimac and his colleague Nebojsa Hodak then picked up the lifeless body of 12-year-old Aleksandra Zec, dressed in pink pyjamas, and threw her in a pre-prepared pit in which the body of her mother Marija – killed only moments earlier – was already lying.

Hearing someone’s last breath in the pit, Igor Mikola, another unit member, fired a round at Aleksandra and Marija to make sure neither remained alive.

After burying the bodies, police officers threw some trash over the burial site to further cover their tracks, which were covered by snow where the pit have been dug on Mount Medvednica, overlooking Zagreb.

Aleksandra and Marija Zec, who were Croatian Serbs, were kidnapped from their family home in Zagreb around midnight on December 7, 1991, after witnessing the murder of the girl’s father, local businessman Mihajlo Zec.

In the botched prosecution that followed, all five policemen were acquitted. Many of the unit’s members received medals, while Rimac was even made responsible for the security of wartime Defence Minister Gojko Susak.

The unofficial name of the unit was the Mercepovci (Mercep’s Men). It got itself a notorious image in the 1990s, and the wider public became more or less familiar with its criminal deeds.

But the murder of the Zec family was not an isolated incident. It was more or less the modus operandi of the unit.

“My name is Miro Bajramovic, and I’m directly responsible for the deaths of 86 people. Knowing this fact, I fall asleep at nights and get up in the morning if I fall asleep at all,” ,” Bajramovic, another of Mercep’s men, told the weekly magazine Feral Tribune in 1997.

“I alone have killed 72 people, including nine women. We did not differentiate; we did not ask anything; for us, they were Chetniks [derogatory term for Serbs during the 1990s war] and enemies. The hardest thing was to burn the first house and kill the first man. After that, everything goes according to a pattern,” Bajramovic said.

After years on trial, in 2017 the Supreme Court sentenced Mercep to seven years in prison for not preventing or sanctioning his subordinates who killed 43 civilians, mostly Serbs, in 1991 and 1992. Although he was initially indicted for ordering the crimes, the prosecution amended the indictment as the trial was reaching its end.

‘Who hasn’t fired yet?!’

“You aren’t going to kill us, you aren’t going to shoot us,” an elderly Serb women shouted as they were taken to the execution site near Gospic in October 1991.

Mirko Norac told his men that everyone would be given someone to kill. To set an example, he takes out his pistol and shots an elderly woman in the head. He then tries to kill a younger prisoner, but his pistol seizes up and fails to fire three times, and he gives up.

“Fire! Fire! Who hasn’t fired yet?!” he screams to his subordinates, wanting them all as accomplices in the murder of at least 50 Serb civilians.

Less than two years after these killings, in the same region, Gospic, Norac was involved in another huge crime. During the ‘Medak Pocket’ operation, aimed at pushing back Croatian Serb forces from Gospic, the Croatian Army took control of a few villages, capturing some Serb soldiers and elderly villagers.

During and after the operation, some of the Croatian soldiers showed unprecedented brutality, killing 22 civilians and two prisoners of war, some through torture. The atrocities included putting salt on wounds and soldiers doing target practice with knives using an elderly man who was still alive.

So what happened in 1991 was not an isolated incident; this was also more of less Norac’s modus operandi.

In 2004, Norac was found guilty of the crimes committed in 1991 and sentenced to 12 years in prison. For the crimes committed during the ‘Medak Pocket’ operation, he got six years in 2009.

In the end, he was given a joint 15-year-long sentence. After serving only ten years, Norac was given early release in 2011, despite never expressing remorse.

After prison, profit

Although legally there are no obstacles to sending a war criminal to a medical spa or welcoming a war criminal who “carries his cross”, there are moral issues.

Mercep apparently had a doctor’s prescription for a medical spa treatment, along with his legally-guaranteed veteran’s privileges, but it does look as though he has been getting a better deal than some of his wartime comrades.

While one can live with the fact that war veterans have advantages in receiving medical services, there are many war veterans who struggle to secure a place in a spa for treatment they need.

I am not advocating that prisoners should be kept in solitary confinement, without access to proper medical treatment, or be subjected to torture or made to do forced labour. However, they should not have more privileges than an ordinary citizen who has been waiting for medical treatment for months.

If the status of a war veteran is so sacred, then what about Aleksandar Antic, a Croatian soldier killed in Pakracka Poljana in 1991 by Mercep’s unit, whose body was never recovered? Why isn’t Medved thinking of him and his family?

Meanwhile Norac, as well as the damage he has done, has also cost the state financially; Croatia had to pay tens of thousands of euros in compensation to the families of his victims.

Although the state has tried to force him to pay part of the compensation, Norac should have no complaint about the way the state has treated him.

Upon his release from prison, he got a pension of some 1,350 euros a month – some five times more than an average pension at the time.

Additionally, state companies and institutions have become some of Norac’s biggest clients, buying services from his security company. His company’s income jumped 200 per cent in 2017 compared to the year before.

While justice has evaded Aleksandra Zec and nothing can bring back the dead in Gospic, both Norac and Mercep have been treated rather well.

If their health allows them, the two men will enjoy long lives that will not end like those of their victims. With their pensions, houses and companies, they will have an everyday standard of living that is better than average Croatian citizens.

Therefore, besides their privileges, which are completely in line with legal norms in Croatia, the state shouldn’t offer Norac and Mercep anything more – especially not the respect they have been granted by ministers in recent days, which they clearly do not deserve.

EuroCroatia today: Split, September 14th, 2018.

EuroCroatia today: Split, September 14th, 2018.

The inscription on the car from Serbia: “Kill the Serb”. A photo by the car’s owner

Originally published on 2018-09-14

About the author: Sven Milekic is the outgoing Zagreb correspondent for BIRN’s Balkan Transitional Justice project. This article is written in a personal capacity.

Source: Balkan Insight

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

EuroCroatia today: Croatia’s President Kolinda Grabar Kitarović with a flag of a Nazi-fascist WWII Independent State of Croatia

EuroCroatia today: Croatia’s President Kolinda Grabar Kitarović with a flag of a Nazi-fascist WWII Independent State of Croatia