Views: 2520

The political purpose of Vitezović’s writings

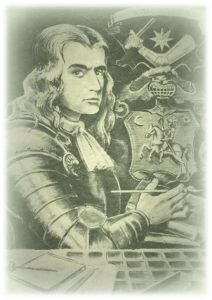

The ultimate political purpose of P. R. Vitezović’s works, based on his ideological construction, was of a triple nature.

First of all, he tried to refute the Venetian claims on the territory of Dalmatia, the Istrian Peninsula, the Dalmatian Islands and Boka Kotorska (Cattaro Gulf in present-day Montenegro) that rose during the Great Vienna War 1683–1699 in which the Republic of St. Marco successfully fought the Ottoman Sultanate in a coalition with the Habsburg Empire [Banac 1984, 73]. The war clearly marked the beginning of the irreversible decline of the Ottoman power which consequently opened the so-called Eastern Question or the question of the destiny of the Ottoman Sultanate in Europe.

A state of the Ottoman dynasty reached its heyday in the mid-16th century when it occupied and annexed most of the Arab world, most of Hungary with Transylvania, Srem, and Slavonia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and many of the islands in the East Mediterranean Sea. The Sultanate also inflicted several heavy naval defeats on Spain, Genoa, and Venice. After the fall in 1521 of a strongest Hungarian military fortress of Belgrade, known as a Gate of Hungary, a way to Central Europe became fully open to the Ottoman army. Subsequently, the biggest part of historical Hungary became occupied up to 1544 including and the biggest portion of present-day Croatia. After the Mohács Battle in 1526, Hungarian, Bohemian and Croatian nobility elected the Habsburg Emperor as their new ruler and protector.

A state of the Ottoman dynasty reached its heyday in the mid-16th century when it occupied and annexed most of the Arab world, most of Hungary with Transylvania, Srem, and Slavonia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and many of the islands in the East Mediterranean Sea. The Sultanate also inflicted several heavy naval defeats on Spain, Genoa, and Venice. After the fall in 1521 of a strongest Hungarian military fortress of Belgrade, known as a Gate of Hungary, a way to Central Europe became fully open to the Ottoman army. Subsequently, the biggest part of historical Hungary became occupied up to 1544 including and the biggest portion of present-day Croatia. After the Mohács Battle in 1526, Hungarian, Bohemian and Croatian nobility elected the Habsburg Emperor as their new ruler and protector.

The Hungarian and Croatian feudal aristocracy hope to reconquer their self-proclaimed historical territories from the Ottomans backed by the Habsburg rulers. Therefore, any kind of revived Hungary or Croatia was possible only within the borders of the Habsburg Monarchy after the military defeat of the Ottoman Sultanate. The House of Habsburgs before 1526 had their family domains only in the region of Alpes: the Upper and Lower Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Gorizia, and Tyrol. However, the invitation to the Habsburg ruler to become the Hungarian-Croatian king in 1526 change dramatically the territorial base of their rule as the Habsburgs started to claim all historical lands of the pre-1526 Kingdom of Hungary including and Croatia-Slavonia and the lands of the Kingdom of Bohemia together with Bohemia itself, Moravia, Silesia and Lusatia (Magocsi 2002: 62). Subsequently, after 1526 the geopolitical aims of the Habsburgs coincided with those of the Hungarian and the Croatian nobility.

An example of the Spanish Reconquista from 1492 gave a great impetus to the Christian Central European nobility in their struggle against Asiatic-Islamic “infidels” who occupied their feudal domains and destroyed their medieval independent states. The European possessions of the Sultanate reached its maximum extent as late as 1676 and in 1683 the Ottomans were enough strong to launch a decisive war for the heartland of Central Europe by putting Vienna under the siege for two months (Bideleux, Jeffries: 1999, 82). However, it was the last attempt by the Sultanate to penetrate deeper into Europe – an attempt which became not only a total military fiasco but much more seriously, the beginning of the final end of the Ottoman state. In 1699, the Sultanate lost all of its Central European possessions opening the doors to the Habsburg Monarchy and Venice to divide between themselves conquered territories from the Sultanate. At such circumstances, it was for the Croatian nobility of the fundamental importance which lands from the Ottoman Sultanate are going to be included into the Habsburg Monarchy as they could count only these territories to be unified with the rest of the Habsburg-ruled Croatia into a separate administrative-territorial province under the name of Croatia. In other words, all South Slavic lands which were left outside the Habsburg Monarchy were lost for a Greater Croatia.

As a result of the Venetian military victory over the Ottoman Sultanate at the end of the Great Vienna War, the officials of the Republic of St. Marco required considerable territorial enlargement of their possessions on the East Adriatic littoral at the expense of both the Ottoman Sultanate and the South Slavs. These territorial demands had been based on the Venetian state-historical and ethnolinguistic rights on the lands and people of the East Adriatic seacoast. It was pointed out in the Venetian territorial claims that Signorina ruled Istria, Dalmatia, and the Adriatic Islands since the year of 1000, strengthening her realm by the further territorial annexations in 1409, 1420, 1433, and 1669.[1] Further, according to the opinion of the Venetian authorities, the majority of the population of the East Adriatic littoral were the Italian-speaking inhabitants, whose wish, natural rights and interest were to be liberated from the Ottoman sway and governed by the Italian-speaking Venice. Due to their military victories over the Ottomans and well-organized propaganda network, the Venetians extended their Dalmatian possessions according to the Peace Treaty of Sremski Karlovci that was signed with the Ottoman Sultanate on January 26th, 1699. However, the treaty was revised on April 15th, 1701 in the Venetian favor by acquisition of whole Peloponnesus/Morea, some islands, the city of Herceg Novi, part of Boka Kotorska, the mouth of the Neretva River and continental Dalmatia up to the Dinaric Range (Istorija naroda Jugoslavije 1960: 777–778; Dimić 1999: 266).

P. R. Vitezović tried to negate the Venetian territorial claims on the South Slavic Adriatic littoral, which was considered by him as a Croatian state-historical and ethnolinguistic territory, which was at the same time a part of the lands of the Hungarian Royal Crown inherited in 1526 by the Habsburg Monarchy. He was actually protesting against the articles of the 1699 Habsburg-Ottoman peace treaty requiring its revision for the sake to include into the Habsburg Monarchy all “Croatian” lands. For that purpose, Vitezović based Croatian territorial claims primarily on state-historical rights – iura municipalia[2] – but combining them to the certain degree as well as with the Croatian ethnolinguistic rights. Subsequently, for instance, the whole territory of Adriatic Dalmatia was appropriated to Croats by Vitezović for the reason that the Croatian King Peter Krešimir IV (1058–1075) included this region into the Croatian medieval state (Fine 1994: 278–279; Klaić 1971: 105–111; Macan 1992: 36–41): “Cresimirus Croatoru Rex Adriaticum Mare suae appropriabat jurisdictioni” (Ritter 1700, 13).

P. R. Vitezović’s writings were especially directed against pro-Venetian texts of the famous historian and doctor of law from Dalmatian city of Trogir – Ivan Lučić (Lucius Joannes 1604–1679) – who is traditionally considered as a founder of the Croatian scientific historiography. I. Lučić’s most important work – De Regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae libri six (“The Kingdom of Dalmatia and Croatia in Six Volumes”), Amsterdam, 1668 – that includes many narrative sources, genealogical tables and historical-geographical maps, tells the historical truth that Dalmatia in former time was a separate territory from the state of Croatia and, in fact, the Venetian possession. However, Vitezović, due to his Croatocentric point of view, used every opportunity to accuse I. Lučić (Lucius) of Dalmatocentric and pro-Venetian, attitude, a subject to which he devoted a whole work under the title Officiae Ioannis Lucii de Regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae Refutatae (“Refutation of Lučić’s Kingdom of Dalmatia and Croatia”) written in 1706. For this purpose, Vitezović referred to the Priest from Doclea who wrote in his chronicle that a synonym for Croatia Alba (White Croatia) is Dalmatia Inferior (the Lower Dalmatia), while a synonym for Croatia Rubea (Red Croatia) is Dalmatia Superior (the Upper Dalmatia) (Ljetopis Popa Dukljanina 1967: 194–196). Clearly, for both the Priest from Doclea and Pavao Ritter Vitezović, Croatia and Dalmatia were the same territories, just with two names.

Second of all, P. R. Vitezović’s political aim was to put all “Croatian” Balkan territories under the sceptre of the Habsburg Emperor Leopold I. The regions in question, which remained outside the borders of Croatia and the Habsburg Monarchy after the Peace Treaty of Sremski Karlovci in 1699, became the object not only of Vitezović’s Croatocentric, but as well as of the Habsburg imperial desires. For instance, during the first peace treaty negotiations between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Ottoman Sultanate in 1689, the Habsburg diplomatic representatives steadily demanded that the eastern frontier of the Habsburg Monarchy had to follow the Morava River (in Serbia). It means that Bosnia-Herzegovina, Srem, Croatia, Slavonia, and West Serbia had unconditionally to be part of the Habsburg Monarchy (Stoye 1994: 71–72).

Being disappointed with the newly established borders accorded by the Peace Treaty of Sremski Karlovci in January 1699 (Weigl 1699), the Croatian representative in the Habsburg Monarchy’s commission for the demarcation, a cartographer and historian Pavao Ritter Vitezović, presented his memorandum, printed under the headline Croatia rediviva…i.e., his view of the “real historical borders and territory of Croatia” (Marković 1987: 71–99; Fürst-Bjeliš 2000: 211–214; Kovačević 1973) to the Habsburg Emperor Leopold I, urging him to liberate and to annex to the Habsburg Monarchy all Cisdanubian “Croatian” territories, what was actually the whole Balkans without Central and South Greece. Surely, Vitezović’s political plan presented to Leopold I fitted to the Habsburg’s plans of the future Habsburg foreign policy. Thus, already in late 1700, after submission of manifesto Croatia rediviva… to the Habsburg authorities, the Habsburg Emperor officially invited Vitezović to visit him in Vienna “since certain and important reasons make your presence in order to provide some information urgently required, also bring all letters and documents delineating and defining borderlines and demarcations of our said Kingdom of Croatia you have on your person…” (Klaić 1914: 105).

The fact is that Leopold I Habsburg, as the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, the King of Hungary and the King of Croatia, started to frequently express the Habsburg hereditary claims on Dalmatia, at the expense of Venice, exactly after the conversation with Vitezović in Vienna. Vitezović himself confirmed that his manifesto was accepted at Viennese imperial court with full attention: “the Viennese are applauding my Prodromus in Croatiam Redivivam I have sent them…” (Lettere del Cavaliere Ritter 1700).

The fact is that Leopold I Habsburg, as the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, the King of Hungary and the King of Croatia, started to frequently express the Habsburg hereditary claims on Dalmatia, at the expense of Venice, exactly after the conversation with Vitezović in Vienna. Vitezović himself confirmed that his manifesto was accepted at Viennese imperial court with full attention: “the Viennese are applauding my Prodromus in Croatiam Redivivam I have sent them…” (Lettere del Cavaliere Ritter 1700).

P. R. Vitezović based his claims on these “Croatian” territories on two principles of legitimization: 1. State-historic rights of Croatia; and 2. The Croatian/Illyrian form of the local place-names as the most reliable marker of the national character (Simpson 1991: 94; Blažević 2000: 228–229). A Croatia Meridionalis (South Croatia) was designed by Vitezović to join the Habsburg Empire, and as a consequence, the whole Balkan Croatia (Illyria) would be politically unified under the Habsburg administration. P. R. Vitezović attempted to institute the piece of evidence that historical borders of the Kingdom of Croatia were considerably larger than those Croatia’s borders established in his time. Beside the far-reaching consequences of the future annexation of Dalmatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina to Croatia, which were according to Vitezović the integral parts of a united historical (but as well as and ethnolinguistic) Croatia, Pavao Ritter Vitezović in fact formulated with his works a political program that would have a significant impact on the 19th-century Croatian national revival, officially named as the Illyrian Movement (Fürst-Bjeliš 2000: 211–214; Perković 1995: 225–236). Shortly, Vitezović protested against the geographical, historical-administrative and ecclesiastical division of “historic” Croatia according to the 1699 peace treaty between the Habsburg Monarchy, the Republic of St. Marco and the Ottoman Sultanate.

Third of all, it can be understood that according to Pavao Ritter Vitezović, the second and final phase of a total “Croatian” historical-ethnolinguistic unification under the Habsburg government should be realized by the Habsburg occupation and annexation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Russian Empire (according to Vitezović, Croatian Sarmatia). It should be pointed out that Bohemia, Moravia, and Lusatia, which were considered by Vitezović as Croatian Venedia, already were parts of the Habsburg Monarchy. A historic Bohemia became integral part of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1526, while Lusatia, which was a part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, was ruled by the members of the Habsburg dynasty as the German Emperors already from 1438 onward (Bérenger 1994: 80–98; Kann 1990: 7; Johnson 1996: 60). Therefore, the final step of a Pan-Croatian political unification should be the annexation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia into the Habsburg Monarchy.

As the matter of fact, this phase of a Pan-Croatian unification started to be realized by the First (1772) and the Third (1795) partition of Poland and Lithuania when Galicia was incorporated into the Habsburg Monarchy in addition to Bukovina (Bukowina) that became included into the Habsburg domains in 1775 (Hammond MCMLXXXIV: 24; Westermann 1985: 115; Kiaupa et al. 2000: 340–358). With partitions of Poland and Lithuania and annexation of Bukovina[3], the parts of the territory of a Transdanubian Croatia Septemtrionalis – “White/Greater Croatia”,[4] became politically unified by the personal union (i.e., by the Habsburg ruler) with the parts of a Cisdanubian Croatia Meridionalis – “Croatia Alba” or West Balkans.

Finally, P. R. Vitezović’s writings had clear (geo)political purpose, being in direct coordination with the Habsburg foreign policy direction at the time. It is a known fact that the Habsburgs laid their territorial claims in Central and South-East Europe on the historical rights of the Hungarian Royal Crown. As the Habsburgs were elected in 1526 by the Hungarian nobility as the kings of Hungary, accordingly, all pre-1526 Hungarian lands are inherited by the Habsburgs. Nevertheless, it was wrongly understood by Vienna that Walachia, Moldavia, Bulgaria, and Serb-populated lands at the Balkans were part of historical Hungary too and therefore had to be liberated from the Ottoman Sultanate and included into the Habsburg Monarchy.

Basically, Vitezović’s idea was to ideologically pave the road to the creation of a unified Croatia with the help of the Habsburg foreign policy as all South Slavs and their lands were already before the Great Vienna War considered by Vienna to be within the Habsburg sphere of interest. As the Hungarian Royal Crown enjoyed even from 1102 hereditary rights on Croatia, the Habsburgs claimed from 1526 all “Croatian” territories as hereditary lands of the Habsburg Monarchy. Subsequently, Vitezović had the only duty to “prove” that all South Slavs are, in fact, ethnolinguistic Croats. He started in 1682 to urge the Habsburg authorities to actively work on the realization of their foreign policy based on arbitrary understood “hereditary rights” of the Hungarian Royal Crown by sending the poetical letter to the Habsburg Emperor Leopold I in which he reminded the Emperor that Dalmatia, Croatia, and Slavonia have to be annexed by the Habsburg Monarchy from the Ottoman Sultanate and the Republic of Venice as these provinces were parts of the pre-1526 Kingdom of Hungary (Dimić 1999: 75). After the Great Vienna War, he continued to urge the Emperor with the new writings on his duty to liberate all “hereditary lands” of the Kingdom of Hungary, but now under the name of revived Croatia (Croatia rediviva).

Basically, Vitezović’s idea was to ideologically pave the road to the creation of a unified Croatia with the help of the Habsburg foreign policy as all South Slavs and their lands were already before the Great Vienna War considered by Vienna to be within the Habsburg sphere of interest. As the Hungarian Royal Crown enjoyed even from 1102 hereditary rights on Croatia, the Habsburgs claimed from 1526 all “Croatian” territories as hereditary lands of the Habsburg Monarchy. Subsequently, Vitezović had the only duty to “prove” that all South Slavs are, in fact, ethnolinguistic Croats. He started in 1682 to urge the Habsburg authorities to actively work on the realization of their foreign policy based on arbitrary understood “hereditary rights” of the Hungarian Royal Crown by sending the poetical letter to the Habsburg Emperor Leopold I in which he reminded the Emperor that Dalmatia, Croatia, and Slavonia have to be annexed by the Habsburg Monarchy from the Ottoman Sultanate and the Republic of Venice as these provinces were parts of the pre-1526 Kingdom of Hungary (Dimić 1999: 75). After the Great Vienna War, he continued to urge the Emperor with the new writings on his duty to liberate all “hereditary lands” of the Kingdom of Hungary, but now under the name of revived Croatia (Croatia rediviva).

To be continued

Note: The text is written according to the orthography of the American (US) English spelling.

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

vsotirovic@yahoo.com

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2018

Personal disclaimer: The author writes for this publication in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.

References:

[1] About the Venetian territorial expansion in the Balkans, see in (Difnik 1986: 330–338; Westermann 1985: 63, 94).

[2] At the time of the feudal order, society and values, the only justifiable rights in international relations were those rights based on the principle of iura municipalia.

[3] Bukovina was in the second half of the 15th century a vassal territory of the Polish-Lithuanian unified state.

[4] According to P. R. Vitezović’s ideological construction, this territory was a motherland of the Czechs, Moravians, Sorbs, Poles, Lithuanians, and Rus’.

Used bibliography:

Anisimov J., 2014: Rusijos istorija nuo Riuriko iki Putino. Žmonės. Įvykiai. Datos. Vilnius.

Banac I., 1983: The Confessional “Rule” and the Dubrovnik Exception: The Origins of the “Serb-Catholic” Circle in Nineteenth-Century Dalmatia, Slavic Review-American Quaterly of Soviet and East European Studies, № 42 (3). 448–474.

Banac I., 1984: The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics. Ithaca and London.

Banac I., 1991a: Hrvatsko jezično pitanje. Zagreb.

Banac I., 1991b: Grbovi biljezi identiteta. Zagreb.

Banac I., 1993: The Insignia of Identity: Heraldry and the Growth of National Ideologies Among the South Slavs, Ethnic Studies, vol. 10. 215–237.

Barišić F., 1961: Vizantijski izvori u dalmatinskoj istoriografiji XVI i XVII veka, Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta, 7. 227–257.

Basanavičius J., 1898: Lietuviškai Trakiškos Studijos. Shenandoah.

Bazala V., 1954: Stric Grgur i nećak Toma Budislavić, Republika, 10, № 2–3. 255–259.

Bérenger J., 1994: A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1273–1700. London and New York.

Bérenger J., 1997: A History of the Habsburg Empire 1700–1918. London and New York.

Bideleux R., Jeffries I., 1999: A History of Eastern Europe. Crisis and Change. London and New York.

Blažević Z., 2000: Croatia on the Triplex Confinium: Two Approaches, in Roksandić D., Štefanec N., (eds.), 2000: Constructing Border Societies on the Triplex Confinium, International Project Conference Papers 2, “Plan and Practice. How to Construct a Border Society? The Triplex Confinium c. 1700–1750” (Graz, December 9–12, 1998). 221–238. Budapest.

Bogišić R., (ed.), 1970: Pavao Ritter Vitezović, “Plorantis Croatiae saecula duo” in Hrvatski latinisti II: Pisci 17–19 stoljeća, vol. 3 of Pet stoljeća hrvatske književnosti, Zagreb.

Bratulić J., (ed.), 1994: Pavao Ritter Vitezović. Izbor iz djela. Zagreb.

Bumblauskas A., 2007: Senosios Lietuvos istorija, 1009−1795. Vilnius.

Bury J. B., 1906: The Treatise De Administrando Imperio, Byzantinische Zeitschrift, XV. 517–577.

Cassio B., 1604: Institutionum linguae illyricae libri duo. Authore Bartholomeo Cassio Curictensi Societatus Iesu. Rome.

Cloke P., Crang Ph., Goodwin M. (eds.) 2009: Introducing Human Geographies, Second edition. London.

Conte F., 1986: Les Slaves. Aux origines, des civilisations d’ Europe centrale et orientale (VI–XIII siècles). Paris.

Ćorović V., 1993: Istorija Srba. Beograd.

Cromer M., 1555: De origine et rebus gestis Polonarum. Basel.

Cronia A., 1952: Contributo alla grammatologia serbo-croata, Ricerche slavistiche, 1. 22–37.

Cronia A., 1953: Contributto alle lessicografia del Dictionarum quinque nobilissimaram Europae linguarum di Fausto Veranzio, Ricerche slavistiche, 2.

Cynarski S., 1968: The shape of Sarmatian ideology in Poland, Acta Poloniae Historica, № 19. 6–17.

Darden B. J., 1997: On Zbignew Gołąb, the Homeland of the Slavs, the Indo-Europeans, and the Venetae, Balkanistica, vol. 10. 430–435.

Davies N., 1981: God’s Playground: A History of Poland, vol. I, The Origins to 1795. Oxford.

Davies N., 1982: God’s Playground: A History of Poland, vol. II, 1795 to the Present. Oxford.

Derkos I., 1832: Genius patriae super dormientibus suis filiis. Zagreb.

Difnik F., 1986: Povijest Kandijskog rata u Dalmaciji (Historia della guera seguita in Dalmatia tra Ventiani e Turchi dall’anno 1645 sino alla pace e separatione de confini). Split.

Dimić Ž., 1999: Veliki Bečki rat i Karlovački mir 1683–1699. Hronologija, Beograd, 1999.

Drašković J., 1832: Disertacija iliti razgovor. Zagreb.

Dukat V., 1925: Rječnik Fausta Vrančića, Rad JAZU, 231. 102–136.

Engel J. (redactor), 1979: Großer Historischer Weltatlas. Zweiter Teil. Mittelalter. München.

Fedorowicz J., (ed.): 1982: A Republic of Nobles: Studies in Polish History to 1864. Cambridge.

Fine J., 1994: The Early Medieval Balkans. A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor.

Franičević M., 1983: Povijest hrvatske renesansne književnosti. Zagreb.

Fürst-Bjeliš B., 2000: Cartographic Perceptions of the Triplex Confinium and State Power Interests at the Beginning of the 18th century, in Roksandić D., Štefanec N., (eds.), 2000: Constructing Border Societies on the Triplex Confinium, International Project Conference Papers 2, “Plan and Practice. How to Construct a Border Society? The Triplex Confinium c. 1700–1750” (Graz, December 9–12, 1998). 205–220. Budapest.

Gabrić-Bagarić D., 1976: Institutiones linguae illyricae Bartola Kašića i težnje ka standardizaciji jezika, Književni jezik, 1–2. 55–68.

Gabrić-Bagarić D., 1984: Jezik Bartola Kašića. Sarajevo.

Gaj Lj., 1835: Horvatov Szloga y Zjedinjenye, Danicza Horvatzka, Slavonzka y Dalmatinzka, January 7th.

Gaj Lj., 1863: Leljiva, Danica ilirska, June 27th.

Gaj Lj., 1965: Horvatov sloga i sjedinjenje, in Hrvatski preporod, vol. I. Zagreb.

Gimbutas M., 1985: Primary and Secondary Homeland of the Indo-Europeans, Journal of Indo-European Studies, 13. 185–202.

Gluck W., 1939: Toma Nadalić Budislavić, Pregled, 3, vol. 15, № 183–184. 150–154.

Gołąb Z., 1991: The Origin of the Slavs: A Linguist’s View. Columbus.

Golub I., 1976: Juraj Križanić, Hrvat iz Ozalja-Georgius Krisanich Croata-ili Križanićeva ukorjenjenost u zavičaju, Kaj, časopis za kulturu, 9–12. 100–103.

Gortan V., 1958: Šižgorić i Pribojević, Filologija, 2. 149–152.

Gregoire H., 1944–1945: L’origine et le nom des Croates et des Serbes, Byzantion, XVII. 88–118.

Guibernau M., Rex J., (eds.), 1999: The Ethnicity. Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Migration. Oxford.

Hammond, MCMLXXXIV: Historical Atlas of the World. Maplewood.

Hobsbawm E., 2000: Nations and Nationalism since 1870. Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge.

Hutchinson J., Smith A. D. (eds.), 1994: Nationalism. Oxford, New York.

Istorija Jugoslavije (group of authors), 1973. Beograd

Istorija naroda Jugoslavije (group of authors), 1960: Beograd.

Jelić L. (ed.), 1906a: Fontes Historici Liturgiae Glagolito-Romanae a XII ad XIX saeculum, saec. XIII. Krk.

Jelić L. (ed.), 1906b: Fontes Historici Liturgiae Glagolito-Romanae a XII ad XIX saeculum, saec. XIV. Krk.

Jelić L. (ed.), 1906c: Fontes Historici Liturgiae Glagolito-Romanae a XII ad XIX saeculum, saec. XVIII. Krk.

Johnson L. R., 1996: Central Europe. Enemies, Neighbors, Friends. New York and Oxford.

Kamiński A., 1983: The Szlachta of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and their government, in Banac I., Bushkovitch P., Yale Concilium, 1983: The Nobility in Russia and Eastern Europe. New Haven.

Kann R. A., 1990: A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London.

Kapleris I., Meištas A., 2013: Istorijos egzamino gidas: Nauja programa nuo A iki Ž. Vilnius.

Kašić B., 1997: Izabrana štiva. Zagreb.

Kiaupa Z., Kiaupienė J., Kuncevičus A., 2000: The History of Lithuania before 1795. Vilnius.

Klaić N., (ed.), 1972: Izvori za hrvatsku povijest do 1526. godine. Zagreb.

Klaić N., 1971: Povijest Hrvata u srednjem vijeku. Zagreb.

Klaić V., 1914: Život i djela Pavla Rittera Vitezovića (1652–1713). Zagreb.

Kojelavičius (Koialowicz) A. W., 1650/1669 (reprint 1989): Historiae Litvaniae. Dancige, Antverpene.

Kolendić A., 1962: Šest latinskih knjižica štampanih u Krakovu u čast Dubrovčanina Tome Natalisa Budislavića, Zbornik istorije književnosti, SANU, 3. 211–240.

Kovačević E., 1973: Granice bosanskog pašaluka prema Austriji i Mletačkoj republici po odredbama Karlovačkog mira. Sarajevo.

Križanić J., 1661–1667: Razgowori ob wladatelystwu. Cracow.

Križanić J., 1859: Gramatično izkazânje ob Rúskom jezíku. Moscow.

Kvaternik E., 1971: Politički spisi. Zagreb.

Laszowski E., 1923: Putovanje Bartula Kašića po Srijemu g. 1612–1618, Hrvatski list, 4, № 264. 2.

Lettere del Cavaliere Ritter: 1700; Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Fondo Marsili, vol. 709, XIX, letter № 2. Bologna.

Ljetopis Popa Dukljanina, 1969: Титоград.

Lučić I., 1986: O kraljevstvu Dalmacije i Hrvatske. Zagreb.

Lucius J., 1668; De regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae libri sex. Amstelodami.

Macan T., 1992: Povijest hrvatskoga naroda. Zagreb.

Maczak A., 1992: Poland, in Porter R. and Teich M. (eds.), 1992: The Renaissance in National Context. Cambridge.

Magocsi R. P., 2002: Historical Atlas of Central Europe, Revised and Expended Edition. Seattle.

Mallory J. P., 1989: In Search of the Indo-Europeans. London.

Marković M., 1987: Prilog poznavanju djela objavljenih u zagrebačkoj tiskari Pavla Rittera Vitezovića, Starine, 60. 71–99. Zagreb.

Marković M., 1993: Descriptio Croatiae. Zagreb.

Marsigli L. F., 1699: Relazione di tutta la Croazia, considerata per il geografico, politico e economico e militare. Bologna.

Matić T., 1950: Bajraktarijev prijevod Orbinijeva “Il regno degli Slavi”, Historijski zbornik, 3, № 1–4. 193–197.

Mladićević Z., 1994: Simboli srpske državnosti. Kratak istorijski pregled heraldičkog razvoja u Srba. Крагујевац.

Moravcsic G. (ed.), Jenkins R. J. H. (translator), 1949: Constantinus Porphyrogenitus. De Administrando Imperio. Budapest.

Novak G., 1951: Dalmacija i Hvar u Pribojevićevo doba in Pribojević V., O podrijetlu i zgodama Slavena. Zagreb.

Orbin M., 1968: Kraljevstvo Slovena. Beograd.

Orbini M., 1601: Il Regno degli Slavi. Pesaro.

Palmer A., 1970: The Lands Between. A History of East-Central Europe since the Congress of Vienna. London.

Pandžić A., 1988: Pet stoljeća zemljopisnih karata Hrvatske. Zagreb.

Pantelić M., 1965: Glagoljski brevijar popa Mavra iz godine 1460, Slovo, XV−XVI. 94–149.

Pažanin A. (ed.), 1974: Život i djelo Jurja Križanića: Zbornik radova. Zagreb.

Perković Z., 1995: Croatia Rediviva Pavla Rittera Vitezovića, Senjski zbornik, 22. 225–236.

Povest’ vremennyh let (translation, introduction and comments by L. Leger), 1884: Paris.

Pribojević V., 1951: De origine successibusque Slavorum. Zagreb.

Radojčić N., 1950: Srpska istorija Mavra Orbinija. Beograd.

Radojčić N., Šišić F., 1929–1930: Letopis Popa Dukljanina, Slavia, vol. VIII, № 5. 158–182.

Rešetar M., 1915: Toma Nadal Budislavić i njegov Collegium Ortodoxum u Dubrovniku, Rad JAZU, 206. 136–141.

Ritter P. E., 1689: Anagrammaton, sive Laurus auxiliatoribus Ungariae liber secundus. Vienna.

Ritter P. E., 1696: Kronika, Aliti szpomen vsega szvieta vikov. Zagreb.

Ritter P. E., 1699: Responsio ad postulata comiti Marsiglio, in Count Marsigli’s collection, manuscript volume 103, entitled Documenta rerum Croaticarum et Transylvanicarum in Commisione limitanea collecta, fol. 27r-34r, Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna.

Ritter P. E., 1706: Indigetes Illyricani sive Vitae Sanctorum Illyrici. Zagreb.

Ritter P., 1689: Anagrammaton, Sive Lauras auxiliatoribus Ungariae liber secundus. Vienna.

Ritter P., 1700: Croatia rediviva: Regnante Leopoldo Magno Caesare. Zagreb.

Ritter P., 1701: Stemmatographia, sive Armorum Illyricorum delineatio, descriptio et restitutio. Vienna.

Samalavičius S., 1995: An Outline of Lithuanian History. Vilnius.

Samardžić R., 1983: Veliki vek Dubrovnika. Beograd.

Sančević Z., 1991: Povijesne granice Hrvatske i Bosne prema kartografima of 16. do 18. stoljeća, Hrvatska revija, vol. I–II. 17–46.

Šapoka A. (ed.), 1936 (reprint 1989): Lietuvos istorija. Kaunas.

Schmaus A., 1953: Vicentius Priboevius, ein Vorläufer des Panslavismus, Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, 1. 243–254.

Šidak J., 1972: Počeci političke misli u Hrvata-J. Križanić i P. Ritter Vitezović, Naše teme, XVI/7–8.

Simpson C. A., 1991: Pavao Ritter Vitezović; defining national identity in the baroque age. Manuscript. The School of Slavonic and East European Studies. University of London. London.

Šišić F., 1928: Letopis Popa Dukljanina, Beograd–Zagreb.

Šišić F., 1934: Hrvatska historiografija od XVI do XX stoljeća, Jugoslovenska istoriski časopis, I/1–4.

Slukan M., 1999: Kartografski izvori za povijest Triplex Confiniuma. Zagreb.

Šmurlo E. J., 1926: Juraj Križanić: Panslavista o missionario, Rivista di letteratura, arte, storia, 1. 3–4.

Šmurlo E. J., 1927: From Križanić to the Slavophils, Slavonic Review, 6, № 17. 321–325.

Sotirović V., 2000: Nineteenth-century ideas of Serbia “linguistic” nationhood and statehood, Slavistica Vilnensis, Kalbotyra, 49 (2). 7–24.

Sotirović V., 2014: The Idea of Pan-Slavic Ethnolinguistic Kinship and Reciprocity in Dalmatia and Croatia, 1477−1683, Politikos mokslų almanachas (Political Science Almanack), 15. 175−187.

Spasić D., Palavestra A., Mrđenović D., 1991: Rodoslovne tablice i grbovi srpskih dinastija i vlastele. Београд.

Stanojević S., 2015: Svi srpski vladari. Biografije srpskih (sa crnogorskim i bosanskim) i pregled hrvatskih vladara. Beograd.

Šrepel M., 1890: Latinski izvor i ocjena Kašićeve gramatike, Rad JAZU, 102. 172–201.

Stančić N., 1985: Hrvatski narodni preporod, 1790–1848: Hrvatska u vrijeme Ilirskog pokreta. Zagreb.

Starčević A., 1971: Politički spisi. Zagreb.

Štefanić V., 1938: Bellarmino-Komulovićev Kršćanski nauk, Vrela i prinosi, 8. 1–50.

Štefanić V., 1963: Tisuću i sto godina od moravske misije, Slovo, XIII. 5–42.

Stojković M., 1913/1914: Karakteristika života i djelovanja Bartula Kašića iz Paga, Nastavni vjesnik, 22, № 1. 1–9.

Stojković M., 1919: Bartuo Kašić Pažanin, Rad JAZU, 220. 170–263.

Stoye J., 1994: Marsigli’s Europe 1680–1730. The Life and Times of Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, Soldier and Virtuoso. New Haven and London.

Sulimirski T., 1945: Schythian Antiquities in Central Europe, The Antiquaries Journal, XXV. 1–26.

Tadin C., 1903: Elio Lampridio Cerva, Rivista Dalmatica, 3, № 6. 265–278.

Težak S., 1996: Naglasci Jurja Križanića i današnji naglasni odnosi na području Ribnika, Ozalja Dubovca, Filologija, 26. Zagreb.

The Sorbs in Germany (group of authors), 1998. Görlitz.

Vanino M., 1934: Bartul Kašić i književni mu rad, Napredak, kalendar, 23. 123–127.

Vanino M., 1936: O Aleksandru Komuloviću, Napredak, kalendar, 26. 40–54.

Vanino M., 1940: Autobiografija Bartula Kašića, Gradja, 15. 1–144.

Velčić M., 1991: Otisak priče. Zagreb.

Verantius F., 1595: Dictionarium quinque nobilissimarum Europae linguarum, Latinae, Italicae, Germanicae, Dalmatiae & Ungaricae. Venice.

Vitezović P. R., 1699: Mappa Generalis Regni Croatiae Totius. Limitibus suis Antiquis, videlicet, a Ludovici, Regis Hungariae, Diplomatibus, comprobatis, determinati. 1:550 000 (drawing in color). 69,4 x 46,4 cm. Hrvatski državni arhiv, Kartografska zbirka (Croatian State Archives, Cartographic Collection), D I. Zagreb.

Vitezović P. R., 1706: Offuciae Ioannis Lucii de Regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae Refutate. Zagreb.

Vitezović P. R., 1997: Oživjela Hrvatska. Zagreb.

Vitezovich P., 1696: Kronika, aliti szpomen vszega szvieta vikov. Zagreb.

Vrančić F., 1971: Rječnik pet najuglednijih evropskih jezika. Zagreb.

Wandycz P., 1974: The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795–1918. Seattle.

Wandycz P., 1992: The Price of Freedom: a History of East-Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present. London.

Wandycz P., 1997: Laisves kaina. Vidurio Rytų Europos istorija nou viduramžių iki dabartines. Vilnius.

Weigl J. Ch. 1699: Mappa der zu Carlovitz geschlossen und hernach durch zwei gevollmächtige. Comissarios vollzogenen Kaiserlich-Türkischen Grantz-Scheidung, in dem früh jahr 1699. angefangen und nach verfliesung 26. Monaten volendet worden. 1:11 300 000. – 1702. – Copperlate in colour; 290 x 365 cm. Hrvatski državni arhiv, Kartografska zbirka (Croatian State Archives, Cartographic Collection) A I 12; Muzej hrvatske povijesti, Kartografska zbirka (Museum of Croatian History, Cartographic Collection) 3844, Biblioteka nacionalnog univerziteta, Kartografska zbirka (National University Library, Cartographic Collection) S-JZ-XVIII-14.

Westermann, 1985: Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte. Braunschweig.

Zamoyski A., 1987: The Polish Way: a One Thousand Year History of the Poles and their Culture. London.

Žefarović H., 1741: Σтемматографϊа. Vienna.

Žic N., 1935: Hrvatske knjižice Aleksandra Komulovića, Vrela i prinosi, 5. 162–181.

Zinkevičius Z, 2013: Lietuviai: Praeities dydybė ir sunykimas. Vilnius.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS