Views: 1451

Thanksgiving recalls for many people a meal between European colonists and indigenous Americans that we have invested with all the symbolism we can muster. But the new arrivals who sat down to share venison with some of America’s original inhabitants relied on a raft of misconceptions that began as early as the 1500s, when Europeans produced fanciful depictions of the “New World.” In the centuries that followed, captivity narratives, novels, short stories, textbooks, newspapers, art, photography, movies and television perpetuated old stereotypes or created new ones — particularly ones that cast indigenous peoples as obstacles to, rather than actors in, the creation of the modern world. I hear those concepts repeated in questions from visitors to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian every day. Here are five of the most intransigent.

Thanksgiving recalls for many people a meal between European colonists and indigenous Americans that we have invested with all the symbolism we can muster. But the new arrivals who sat down to share venison with some of America’s original inhabitants relied on a raft of misconceptions that began as early as the 1500s, when Europeans produced fanciful depictions of the “New World.” In the centuries that followed, captivity narratives, novels, short stories, textbooks, newspapers, art, photography, movies and television perpetuated old stereotypes or created new ones — particularly ones that cast indigenous peoples as obstacles to, rather than actors in, the creation of the modern world. I hear those concepts repeated in questions from visitors to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian every day. Here are five of the most intransigent.

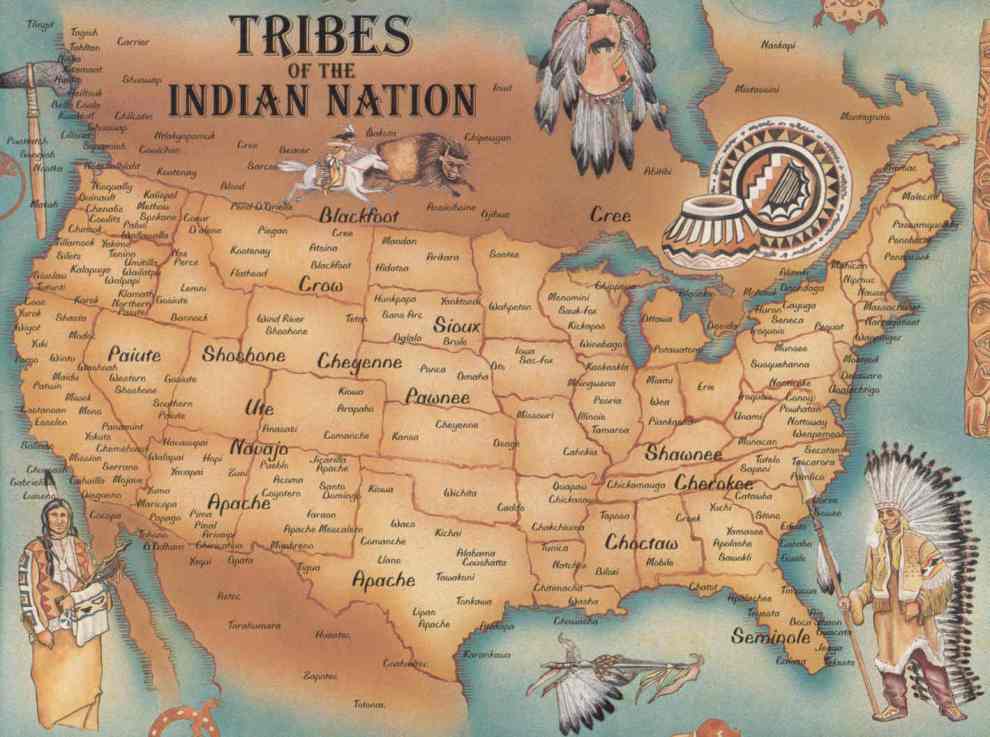

This concept really took hold when Christopher Columbus dubbed the diverse indigenous inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere “Indians.” Lumping all Native Americans into an indiscriminate, and threatening, mass continued during the era of western expansion, as settlers pushed into tribal territories in pursuit of new lands on the frontier. In his 1830 “Message to Congress,” President Andrew Jackson justified forced Indian removal and ethnic cleansing by painting Indian lands as “ranged by a few thousand savages.” But it was Hollywood that established our monolithic modern vision of American Indians, in blockbuster westerns — such as “Stagecoach” (1939), “Red River” (1948) and “The Searchers” (1956) — that depict all Indians, all the time, as horse-riding; tipi-dwelling; bow-, arrow- and rifle-wielding; buckskin-, feather- and fringe-wearing warriors.

This concept really took hold when Christopher Columbus dubbed the diverse indigenous inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere “Indians.” Lumping all Native Americans into an indiscriminate, and threatening, mass continued during the era of western expansion, as settlers pushed into tribal territories in pursuit of new lands on the frontier. In his 1830 “Message to Congress,” President Andrew Jackson justified forced Indian removal and ethnic cleansing by painting Indian lands as “ranged by a few thousand savages.” But it was Hollywood that established our monolithic modern vision of American Indians, in blockbuster westerns — such as “Stagecoach” (1939), “Red River” (1948) and “The Searchers” (1956) — that depict all Indians, all the time, as horse-riding; tipi-dwelling; bow-, arrow- and rifle-wielding; buckskin-, feather- and fringe-wearing warriors.

Yet vast differences — in culture, ethnicity and language — exist among the 567 federally recognized Indian nations across the United States. It’s true that the buffalo-hunting peoples of the Great Plains and prairie, such as the Lakota, once lived in tipis. But other native people lived in hogans (the Navajo of the Southwest), bark wigwams (the Algonquian-speaking peoples of the Great Lakes), wood longhouses in the Northeast (Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois peoples’ name for themselves, means “they made the house”), iglus and on and on. Nowadays, most Native Americans live in contemporary houses, apartments, condos and co-ops just like everyone else.

There is similar diversity in how native people traditionally dressed; whether they farmed, fished or hunted; and what they ate. Something as simple as food ranged from game (everywhere); to seafood along the coasts; to saguaro, prickly pear and cholla cactus in the Southwest; to acorns and pine nuts in California and the Great Basin.

The notion that indigenous people benefit from the government’s largesse is widespread, according to “American Indians: Stereotypes and Realities,” by Choctaw historian Devon Mihesuah. Staff and volunteers at our Washington and New York museums hear daily about how Washington “gave” Native Americans their reservations and how the Bureau of Indian Affairs manages their lives for them.

In 1879, a landmark case asked the question: Are Native Americans considered human beings under the U.S. Constitution? This is Chief Standing Bear’s story.

But Native Americans are subject to income taxes just like all other Americans and, at best, have the same access to government services — though often worse. In 2013, the Indian Health Service (IHS) spent just $2,849 per capita for patient health services, well below the national average of $7,717. And IHS clinics can be difficult to access, not only on reservations but in urban areas, where the majority of Native Americans live today.

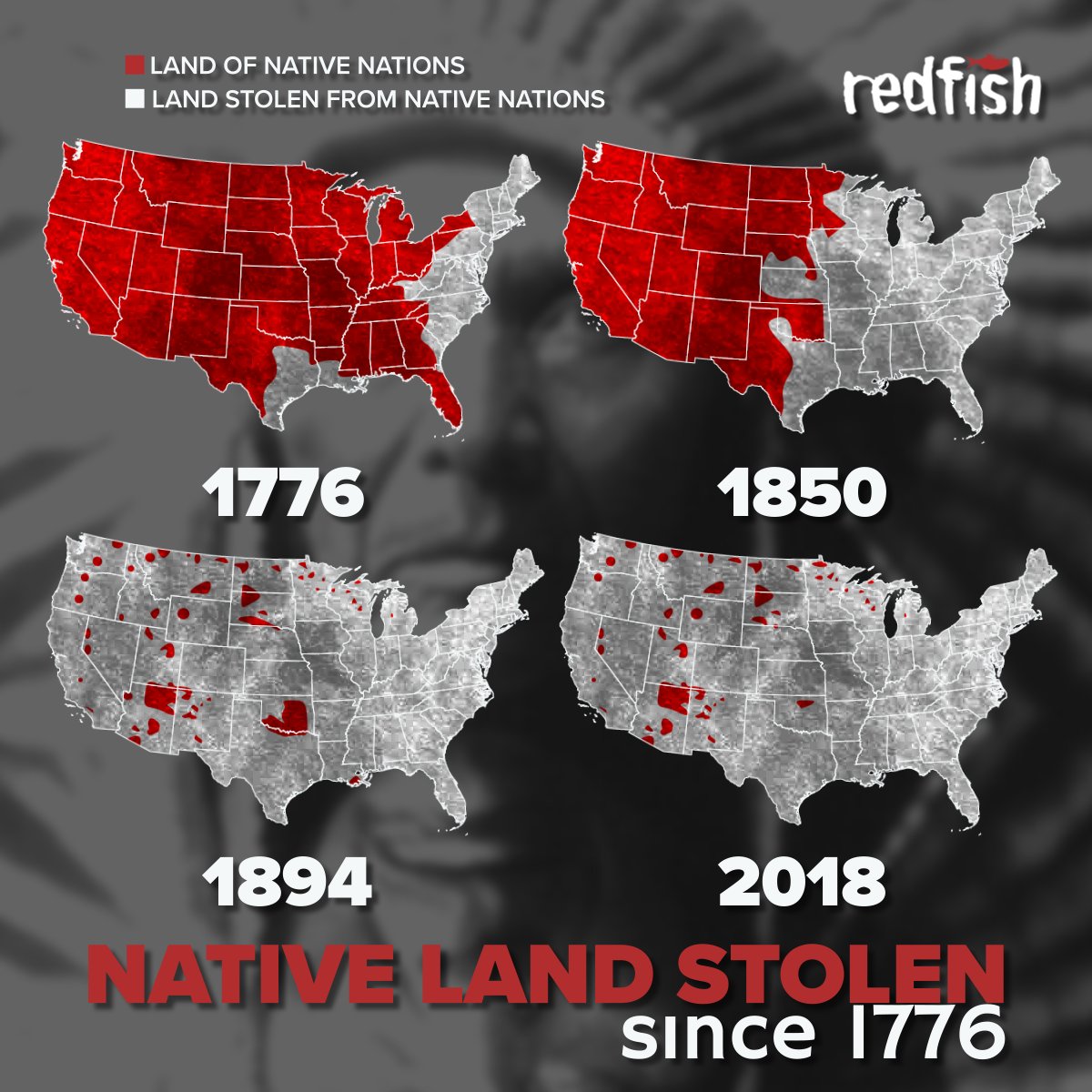

As for reservations, most were created when tribes relinquished enormous portions of their original landholdings in treaties with the federal government. They are what remained after the United States expropriated the bulk of the native estate. And even these tenuous holdings were often confiscated and sold to white settlers. The Dawes Allotment Act, passed by Congress in 1887, broke up communally held reservation lands and allotted them to native households in 160-acre parcels of individually owned property, many of which were sold off. Between 1887, when the allotment act was passed, and 1934, when allotment was repealed, the Native American land base diminished from approximately 138 million acres to 48 million acres.

Commentaries and corporate guidelines address the notion that “Native American” is preferred or that “American Indian” is impolite. During the 1492 quincentennial, Oprah Winfrey devoted an hour of her show to the subject. At the museums and on social media, people ask at least once per day when we are going to take “American Indian” out of our name.

The term Native American grew out of the political movements of the 1960s and ’70s and is commonly used in legislation covering the indigenous people of the lower 48 states and U.S. territories. But Native Americans use a range of words to describe themselves, and all are appropriate. Some people refer to themselves as Native or Indian; most prefer to be known by their tribal affiliation — Cherokee, Pawnee, Seneca, etc. — if the context doesn’t demand a more encompassing description. Some natives and nonnatives, including scholars, insist on using the word Indigenous, with a capital I. In Canada, terms such as First Nations and First Peoples are preferred. Ditto in Central and South America, where the word indio has a history of use as a racial slur. There, Spanish speakers tend to use the collective word indígenas, as well as specific national names.

This myth — repeated in textbooks and made vivid in illustrations — casts Native Americans as gullible provincials who traded valuable lands and beaver pelts for colorful European-made beads and baubles. According to a letter to Dutch officials, the settlers offered representatives of local Lenape groups 60 guilders, about $24, in trade goods for their homeland, Manahatta. The best insight we have into what the Lenape received comes from a later 17th-century deed for the Dutch purchase of Staten Island, also for 60 guilders, which lists goods “to be brought from Holland and delivered” to the Indians, including shirts, socks, cloth, muskets, bars of lead, powder, kettles, axes, awls, adzes and knives. The Dutch recognized the mouth of the Hudson River as a gateway to valuable fur-trapping territories farther north and west.

But it is unlikely that the Lenape saw the original transaction as a sale. Although land could be designated for the exclusive use of prominent native individuals and families, the idea of selling land in perpetuity, to be regarded as property, was alien to native societies. Historians who try now to reconstruct early transactions between Europeans and Native Americans differ over whether the Lenape considered it an agreement for the Dutch to use, but not own, Manahatta (the majority view), or whether even as early as 1626, Indians had engaged in enough trade to understand European economic ideas.

Many people, including some American Indians , hold that naming sports teams after Native American caricatures, such as the Redskins and the Braves, recognizes the strength and fortitude of native peoples. “It represents honor, represents respect, represents pride,” Redskins owner Dan Snyder told ESPN.

A little history: The use of Native Americans as mascots arose during the allotment period, a time when U.S. policy sought to eradicate native sovereignty and Wild West shows cemented the image of Indians as plains warriors. (No wonder all of these mascots resemble plains Indians, even when they represent teams in Washington, Florida and Ohio.)

What’s more, social science research suggests not only that some native people recognize the word “Redskins” as a racial slur and are offended by it, but that exposure to mascots and other stereotypes of Native Americans has a negative impact on American Indian young people. According to a study by Tulalip psychologist Stephanie Fryberg, such mascots “remind American Indians of the limited ways others see them and, in this way, constrain how they can see themselves.” Likewise, in 2005, the American Psychological Association called for the retirement of all Indian mascots, symbols and images, citing the harmful effects of racial stereotyping on the social identity and self-esteem of American Indian youth.

Originally published on 2017-11-22

About the author: Kevin Gover, a citizen of the Pawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, is the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Source: The Washington Post

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS