Views: 1973

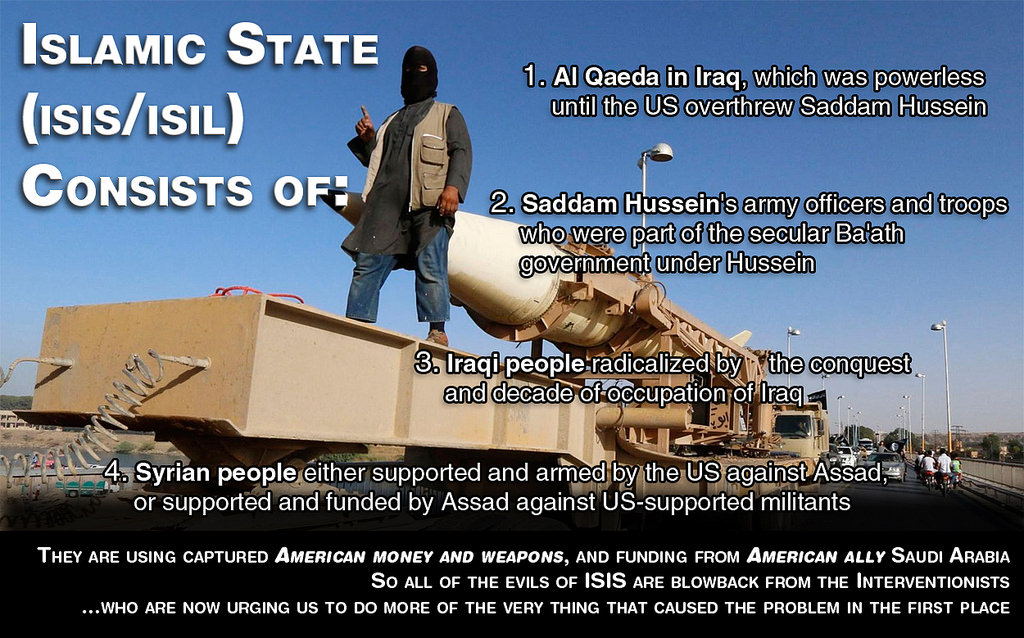

ISIS is Born in Iraq

The origins of ISIS are buried beneath the rubble of the US occupation.

It was out of this crucible of war and invasion that the original grievances were born, leading analysts to conclude that “the basic causes of the birth of ISIS” were the United States’ “destructive interventions in the Middle East and the war in Iraq.”1

The framework underlying this being the exacerbation of Sunni-Shia tensions in the aftermath of the invasion, which previously have been inflamed through various other foreign interferences. These were highlighted by the sectarian brutality of the post-invasion Iraqi government, which then continued under Maliki later on. Given this, some have concluded that Saddam had simply been replaced by another “repressive and murderous authoritarian state, albeit under a more representative sectarian set up.”2

Out of this sectarian nexus, a man known by the name of al-Zarqawi was able to bring together various groups of jihadists under the umbrella of “al-Qaeda in Iraq” and lay the foundations for a sort of governmental structure which could evolve into an eventual Islamic state. A veteran of the jihad in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union in the 1980s, Zarqawi had reportedly obtained sanctuary in Iran where he accumulated weapons and equipment before later returning to Iraq to oppose the US occupation.4

Following al-Zarqawi’s death at the hands of a US airstrike, a new federation of jihadists then established the “Islamic State in Iraq” by the end of 2006, although it was at first marked by widespread defections as the Sunni insurgency was then losing momentum. However, evidence reveals that Syria’s Bashar al-Assad had helped the insurgents by facilitating the flow of jihadists into Iraq, in an apparent attempt to jeopardize the US occupation and thereby prevent against a similar US attack against Syria.5

Yet what really allowed ISI to expand its influence were the abuses and violence perpetrated by the US military.6 Rising to power during his imprisonment in the infamous Camp Bucca, the group was rejuvenated under the enhanced leadership of the mysterious to-be-named al-Baghdadi.

However, it is widely accepted that the Camp Bucca prison served as a sort of training ground or “jihadist university” from which the eventual Islamic State was born. The networks Baghdadi established there going on to form the upper echelons of the groups top leadership. Indeed, without such military detentions “it would have been impossible for so many like minded jihadists and insurgents to have met together safely in Iraq at that time without such a protective atmosphere as Bucca.” In this sense, a former inmate explains that the US did “a great favor” for the mujahideen, having “provided us with a secure atmosphere, a bed and food, and also allowed books giving us a great opportunity to feed our knowledge with the ideas of al-Maqdisi and the jihadist ideology.”7

Yet the round-ups conducted by the US army were indiscriminate and civilians were targeted wholesale, estimates from 2006 confirming that only 15% of detainees were true adherents of any kind of extremist ideology.8 Yet now jihadists leaders like Baghdadi were given an opportunity to further radicalize others, prisoners explaining how “under the watchful eye of the US soldiers”, “new recruits were prepared so that when they were freed they were ticking time bombs”, not the least of which due to the extensively documented abuses and torture that took place there as well.9

Concurrent with this was a covert attempt by the US military to defeat al-Qaeda in Iraq by fostering alliances with other al-Qaeda-affiliated Sunnis. Spelled out and confirmed by an army-commissioned Rand report, the strategy was to utilize groups like ISI, who, although having fought against the US military, could be counted on to “sow divisions in the jihadist camp” by fighting against al-Qaeda, and thereby the US could exploit “the common threat that al-Qaeda now poses to both parties.”

Mass releases from Bucca were therefore orchestrated in an attempt to augment the strategy with manpower and engender support from the local Sunni tribes. And while the strategy in a sense succeeded, at the same time, it also emboldened another segment of disgruntled Sunnis, when the original causes of their resentments were continuing under the anti-Sunni repression of the US-backed government. The resulting sectarian violence pushed other Sunnis into supporting ISI as the lesser of the two evils, further entrenching the groups foothold in the country.10 Yet this was only half of the story.

By this time influential policy planners were already thinking up other strategic uses which could be gleaned from supporting these disgruntled Sunni radicals.

The accelerated relationship then forming between Maliki and Iran had greatly distressed the White House. Fearing an Iranian-dominated Iraq more so than a resurgence of al-Qaeda, in the context of a “redirection” of US policy against Iran, it was thought that “ties between the US and moderate or even radical Sunnis could put fear into the government of Prime Minister Maliki.” The reasoning was that an alliance with Sunni extremists would be useful as it would “make [Maliki] worry that the Sunnis could actually win the civil war there”, and thus encourage him to cooperate with the US.11 Therefore, in order to remedy the Iranian influence spreading throughout the Maliki government, clandestine operations were adopted, the byproduct of which being the “bolstering of Sunni extremist groups that espouse a militant vision of Islam and are hostile to America and sympathetic to Al Qaeda.”12

The Fake Arab Spring

With the eruption of the crisis in Syria and the subsequent lack of state authority that came with it, ISI was able to exploit the power vacuum and expand its grasp beyond Iraqi borders, changing its name to the “Islamic state in Iraq and al-Sham/the Levant” or ISIS/ISIL to reflect this greater reach.13

The Syrian crisis itself represents just one part in a much larger strategy by the Western powers aimed at manipulating the trajectory of the Arab Spring uprisings to ensure that they ultimately serve the regional agenda of the West. Having successfully thwarted the threats faced from the self-determination and pro-democracy uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen, similar but smaller protests in Syria and Libya were covertly redirected into a pretext for attacking uncooperative regimes which had historically proven antagonistic to Western interests.14

The uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen all threatened to wrestle away the status-quo systems of control that the Western powers had exerted in these countries for almost half a century. This had ensured that foreign corporations maintained easy access to valuable markets and resources and that profits flowed primarily to Western investors.15

This framework of neoliberal reform began to be implemented during the 1970’s when Arab republics were struggling amidst the impacts of global economic downturns and began to institute policies largely directed from above by international finance institutions (IFIs) such as the IMF and World Bank. Given that the IFIs had been increasingly dominated by Western governments, they primarily represented the interests of the financial elite from wealthy Western countries. Therefore, the models they suggested were of rapid economic liberalization and denationalization which on the one hand gave Arab administrations immediate financial relief, yet at the same time, made their economies increasingly vulnerable to exploitation by Western multinational corporations and financial institutions.16 As some have described, such policies had the effect of “massively restricting the ability of [these] governments to promote policies in their own national interests”, as they promoted rules which the UN explained “reflect an agenda that serves only to promote dominant corporate interests”, while at the same time rejecting the kind of policies that historically have been shown to achieve developmental success, such as import controls, taxes on foreign corporations, and state interference in the private sector.17

These policies resulted in the emergence of a growing state-bourgeoisie which was able to enrich itself in a nepotistic fashion through its proximity to influential players within the state sector, allowing connected persons and groups primary access to newly privatized assets which they were able to monopolize and monetize.18 These local elites served the function of clients of the Western powers which insured that the vast bulk of the country’s wealth would flow outwards and into the hands of foreign investors, resulting in a system of modern day neo-colonialism from which the United States and other previously colonial regimes were able to maintain effective control of the region and its resources.19

Apart from the liberalization of resources the prescriptions adopted from the IFIs included the removal of labor rights, the weakening of trade unions, increases in worker instability, tax advantages for foreign corporations, and the privatization of welfare systems.20 This lead to massive increases in inequality, large concentration of wealth, and an erosion of the previous Cold War-era social contract which had traded economic security for political quiescence to authoritarian political structures.21

As these policies advanced these states were increasingly unable to meet the basic needs of their citizens, and the compounding socio-economic pressures led to the rediscovery of long-suppressed notions of Arab dignity and self-determination which became personified within the Arab Spring protests. In this way, the Arab Spring was primarily a result of “people being drawn to the streets by the pressing economic grievances and uneven development that are the result of more than thirty years of neo-liberal policies.”22

Such movements were naturally a major threat to the established systems of power, primarily being centered around social justice and the rebuilding of domestic welfare states that threatened to unseat supplicant and compliant regimes with more assertive and indigenously representative administrations.23 Too much of a challenge for the Western powers to bear, externally-directed counterrevolutions were conducted to insure that such movements would be co-opted and redirected so that the governments which resulted would maintain as much of the previous order as possible, thereby insuring that the threatening ambitions for democracy and self-governance were effectively crushed.24

However, for states which at the same time sat astride coveted natural resources and had long frustrated the ambitions of Western powers to gain greater access, local protests represented a golden opportunity to overturn non-compliant regimes under the pretext of Arab Spring humanitarian and democratic concerns.25 The idea was, as Durham University’s Christopher Davidson explains, to give “ostensibly similar but evidently much smaller-scale protest movements in Libya and Syria the sort of outside helping hand they needed to become full-blown and state-threatening insurgencies.”26 Thus, those Western states which had insured the failure of progressive Arab Spring movements throughout the region, “soon took the concurrent role of funding and weaponizing a fraudulent and more violent Western-sponsored version of the Arab Spring” in both Libya and Syria.27 The cause of such bloody crisis therefore, being a result of these states having been “deliberately targeted in a calculated and sustained manner by external actors who saw a strategic use in supporting and boosting the ambitions of local oppositionists.”28

The “fake Arab Spring” and subsequent civil wars that resulted from these externally-directed and Western-backed insurgencies nevertheless were successful at insuring the failure of the protesters ambitions while as well providing the perfect environment for radicalized extremist organizations to expand their reach and control over territory.29 Such a situation was further encouraged and facilitated by the Western powers who, as previously explained, saw such groups as strategically beneficial foot-soldiers which could be utilized and directed against their enemies.

Notes here

The “Moderate” Jihad in Syria

Syria was externally targeted because the US and its allies saw it as strategically beneficial to organize and foster an armed insurgency which could eventually become capable of overturning the government. The most prominent aspect of this being the attempt to create a “Free Syrian Army” of opposition fighters which could be displayed as the respectable and indigenous face of the insurgency and help sell the intervention to the Western public.

Helping to hide the foreign hand behind the militants, the rebel arming program was only officially announced in 2013, yet in reality began almost two years prior, at least as early as October 2011 after the fall of Gaddafi in Libya, but likely even much earlier.1 Also dispelling the illusion that these FSA groups were solely a native development, it was revealed in late 2011 that US Special Operations Forces were on the ground and privately discussing to themselves how “there isn’t much of a Free Syrian Army to train right now”, the groups only later gaining prominence as a result of the foreign interference.2

Indeed, by this time knowledgeable academics such as Columbia University’s Joseph Massad were writing that the “[Arab] League and imperial powers have taken over the Syrian uprising in order to remove the al-Assad regime”, while the West’s best journalists would later characterize the program by saying “the impression one gets is of a movement wholly controlled by Arab and Western intelligence agencies.”3 Corroborating much of this, a former rebel explained to the Wall Street Journal how the insurgency was largely being directed from abroad, saying that “decisions weren’t always being made at the local level.” Instead, it was “the Salafists from Gulf nations… and the Muslim Brotherhood in Turkey” who would “send money to certain groups and then orchestrate attacks from afar.”4

Concurrently, great efforts were made to portray the FSA as an entirely independent outfit and to separate Western involvement from the extremist groups that were beginning to form. However, apart from whatever the rebels would tell the Western press, the reality on the ground was that there was never any division between the FSA and groups like al-Qaeda, the Islamists having been welcomed from the very start.5 For instance, the founder of the FSA, Syrian army defector Riad el-Asaad, described al-Qaeda as “our brothers in Islam”, while another rebel commander, a main recipients of US aid, admitted that his organizations was very much alike al-Qaeda and that the two groups fought alongside each other. Al-Qaeda did not, he said, “exhibit any abnormal behavior, which is different from that of the FSA.”6 So while US officials maintained that they only supported “moderates”, journalist Patrick Cockburn gets much closer to the truth, explaining that “it is here that there was a real intention to deceive”, because “in reality, there is no dividing wall between them [ISIS and al-Qaeda] and America’s supposedly moderate opposition allies.”7

Also troubling for the oppositions’ image, the “moderate” nature of the US vetted groups soon began to unravel, the FSA consistently being described as even worse than the groups who are commonly associated with extremism. While Department of Defense officials were aware that the “vast majority of moderate Free Syrian Army rebels were in fact, Islamist militants”, counterterrorism specialists explained that the “undisciplined and brutal behavior of the FSA stood in contrast to the much more disciplined Jabhat Al-Nusra.” Indeed, the British press described this brutal behavior in terms of their “looting and banditry”, explaining that “the FSA has now become a largely criminal enterprise” as they have been primarily focused on “profiteering, gun-running, and the extracting of tolls from road checkpoints.”8

Also quite troubling, being enmeshed with the other fighters the FSA had soon assumed the de-facto function of serving as a weapons conduit to the extremists. While it was later confirmed that at least half of all supplies given to the “moderates” were duly handed over to al-Qaeda,9 multiple court cases earlier revealed that arms shipments received by the FSA would be unloaded and distributed quite indiscriminately to whoever was fighting nearby. Helping to explain this, former MI6 agent Alastair Crooke pointed out that “the West does not actually hand the weapons to al-Qaeda, let alone ISIS… but the system that they have constructed leads precisely to that end.” This is because the weapons shipments given to the FSA “have been understood to be a sort of ‘Wal Mart’ from which the more radical groups would be able to take their weapons and pursue the jihad”, as weapons always migrated “along the line to the more radical elements.”10

This wasn’t something that the Western backers of the opposition just turned a blind eye to, instead such cooperation with jihadists was explicitly ordered by them on multiple occasions, usually when the extremists were needed to win battlefield victories. In 2014, for example, a CIA-backed commander explained that “if the people who support us [the US and its allies] tell us to send weapons to another group, we send them. They asked us a month ago to send weapons to [hard-line Islamists] in Yabroud so we sent a lot of weapons there.”

On a separate occasion, US-led operations rooms “specifically encouraged a closer cooperation with Islamists commanding frontline operations” during the conquest of Idlib, the supervision given by US military intelligence operatives being “instrumental in facilitating their [Islamists’] involvement.”11

Enter the Proxies

Having successfully kept most of this hidden from view, focus on the FSA program helped to distract from the wider reality that the US and its allies were supporting the entire opposition indiscriminately.

It has long been known that states like Qatar had been supporting both al-Qaeda and ISIS,12 their own deputy foreign minister openly stating “I am very much against excluding anyone at this stage, or bracketing them as terrorists, or bracketing them as al-Qaeda given Qatar’s perceived necessity of removing al-Assad at all costs.” As well, al-Qaeda’s Syria franchise themselves admitted that they “get money from the Gulf” with their “great name.”13 Also widely known is that Saudi Arabia and Turkey both had intimate ties with al-Qaeda, ISIS, and the rest of the other radical jihadists. Far from trying to hide these connections, both countries had in fact openly supported a rebel coalition that was dominated by al-Qaeda.14 Yet in reality this was all undertaken in cooperation with the United States or with their implicit blessing.

Getting to the heart of the matter, an extensive investigation by Foreign Policy’s Elizabeth Dickenson uncovered that not only had Qatar gotten “such freedom to run its network for the last three years because Washington was looking the other way,” but that “in fact, in 2011, the US gave Doha de facto free rein to do what it wasn’t willing to do.”15 White House officials explained that “Syria is [Qatar’s] backyard”, while academics similarly concluded “there is no chance that Qatar is doing this alone.”16

Indeed, the weapons shipments coming from Qatar had been conducted in conjunction with the CIA, who US officials confirm acted in a “consultant role.“17 In the case of Saudi Arabia, whose former foreign minister himself admitted that it was the Saudi monarchy who created ISIS, stating “Daesh [ISIS] is our [Sunni] response to your support for the Da’wa [Iran-aligned Shia ruling party of Iraq]”,18 their involvement was also conducted jointly with the US. The terms of this arrangement, revealed by The New York Times, was that the Saudis would provide large sums of money and weapons and in exchange would be granted a seat at the table and have a say as to which groups would be supported, while the CIA would coordinate such shipments and help train the fighters.19 Seemingly finding no objections from their US partners, we now know that they and other Gulf allies were the ones “who fund [ISIS]”, as was revealed by then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in congressional testimony.20 Similarly, while it was revealed that Turkey’s intimate coordination with ISIS was “undeniable”,21 in fact evidence suggests the country’s weapons shipments were largely conducted in cooperation with CIA officers and US officials,22 cooperation which continued even as it was revealed that Turkey was collaborating with ISIS and allowing substantial tracts of its territory to remain open to the group.23

Honest reporters therefore correctly categorized the US’ involvement by explaining that “the U.S. in many ways is acting in Syria through proxies, primarily Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates”, while Turkey was “taking the lead as U.S. proxy.”24 Western officials however began to publicly distance themselves from this involvement, claiming the “US had growing concerns that, just as in Libya, the Qataris are equipping some of the wrong militants.” This was worrying because “this has the potential to go badly wrong… [because of] the risk that weapons will end up in the hands of violent anti-Western Islamists.”25 Yet as Christopher Davison explains, whom the Economist describes as “one of the most knowledgeable academics writing about the region”, this was all an attempt to “establish some distance” between the US and its allies in the Gulf, “so as to insulate themselves from any possible fallout from such risky moves.”26

Describing the true relationship, a former advisor to one of the Gulf states explained that the reason the US did not try to stop nations like Qatar from delivering weapons to extremists was simply because “they didn’t want to.”27

The reason the Western powers were supporting such virulent elements was actually quite simple. Besides having a well-documented history of supporting jihadist networks against their enemies,28 the most radical groups taking part in the Syria conflict were as well the best and most effective fighters. Joshua Landis, a US academic and specialist on Syria, explained that the “radicals got money because they were successful. They fought better, had better strategic vision and were more popular.”29 Helping to explain the thought process further, prominent think-tank analysts actually recommended supporting al-Qaeda under the basis that they bring “discipline, religious fervor, battle experience from Iraq, funding from Sunni sympathizers in the Gulf,” and most importantly, “deadly results.”30

Therefore, as former British diplomat Alastair Crooke explains, the operative idea was to “use jihadists to weaken the government in Damascus and to drive it to its knees to the negotiating table.”31

Notes here

A Salafist Principality for the West

As the opposition became increasingly sectarian, it was apparent that it was the militant elements and their “deadly results”1 which drove out and supplanted the real moderates.

A leading figure in the early uprisings, Haytham Manna criticized the negative impact that external intervention had on the protest movement. Writing in The Guardian in 2012, he explained that the main effect of taking up arms was to “undermine the broad popular support necessary to transform the uprising into a democratic revolution.” Furthermore, it was the eventual “pumping of arms to Syria [from] Saudi Arabia and Qatar, the phenomenon of the Free Syrian Army, and the entry of more than 200 jihadi foreigners… [that] have all led to a decline in the mobilization of large segments of the population… and in the activists’ peaceful civil movement.” The net result of this being that “the political discourse has become sectarian; there has been a Salafisation of religiously conservative sectors.”2

Going a way to back up this view, Vice President Biden succinctly admitted that in terms of finding “moderates”, in reality “there was no moderate middle because the moderate middle are made up of shopkeepers, not soldiers.” The shopkeepers and reformists being sidelined as the West’s allies, in Biden’s view, “poured hundreds of millions of dollars and tens of thousands of tons of weapons into anyone who would fight against Assad, except that the people who were being supplied were al-Nusra and al-Qaeda and the extremist elements of jihadis coming from other parts of the world.”3

The realization in the White House was that if they realistically wanted their policy to have any success they would have to empower those capable of producing results. “This idea,” Obama remarked, “that we could provide some light arms or even more sophisticated arms to what was essentially an opposition made up of former doctors, farmers, pharmacists and so forth,” in other words, the moderate forces, “and that they were going to be able to battle not only a well-armed state but also a well-armed state backed by Russia, backed by Iran, a battle-hardened Hezbollah, was never in the cards.”4 Instead, as investigative journalist Gareth Porter explains, the US would have to accept “a tacit reliance on the jihadists to achieve [their] objective of putting sufficient pressure on the Assad regime to force some concessions on Damascus.” Obama would have to “hide the reality that it was complicit in a strategy of arming [al-Qaeda]” by maintaining the illusion that an independent “moderate” opposition existed, as this would be “necessary to provide a political fig leaf for the covert and indirect U.S. reliance on Al Qaeda’s Syria franchise’s military success.”5

Indeed, not only was this all well understood by planners, the true extent of the empowerment of extremists was known to decision makers from the beginning. The CIA, for instance, very early on was informing the President in classified assessments that “most of the arms shipped at the behest of Saudi Arabia and Qatar” were “going to hard-line Islamic jihadists, and not the more secular opposition.”6 The man described as the CIA’s “eyes and ears on the ground” in Syria, tasked with drawing up plans for regime change after spending a year meeting with rebels, concluded from his journey that in fact, “there were no moderates.”7

Even earlier the Defense Intelligence Agency was warning officials that events on the ground “are taking a clear sectarian direction” and left no doubt as to who was heading the opposition, stating “the Salafists, the Muslim Brotherhood, and AQI are the major forces driving the insurgency.” Most remarkably, this 2012 report had predicted the rise of ISIS a full two years before it occurred, stating that “if the situation unravels there is the possibility of establishing a declared or undeclared Salafist principality in eastern Syria.” Far from being undesired, in terms of the West, Gulf countries, and Turkey, the report said “this is exactly what the supporting powers to the opposition want, in order to isolate the Syrian regime.“8

Heading the DIA at the time, Michael Flynn confirmed the validity of this report, explaining that he “paid very close attention… the intelligence was very clear.”9 Not only that, he confirmed that his agency sent a constant stream of classified warnings to the White House about these and other predictions, saying that the jihadists were in control of the opposition and that toppling Assad would have dire consequences. By 2013 the assessments were saying that the US’ covert effort “had morphed into an across-the-board technical, arms and logistical programme for all of the opposition, including Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State. The so-called moderates had evaporated… and the US was arming extremists.”

But instead of heeding these warnings there was “enormous pushback” from the Obama administration, Flynn explaining that “I felt that they did not want to hear the truth.” Indeed, according to a Joint Chiefs of Staff advisor, there simply was “no way to stop the arms shipments that had been authorized by the president.” Even though, Flynn said, “if the American public saw the intelligence we were producing daily, at the most sensitive level, they would go ballistic.”10

When asked if this obstinacy was a result of mere negligence on the part of the civilian administration, remarkably Flynn replied “I don’t think they turned a blind eye, I think it was a decision. I think it was a willful decision.” Asked to clarify if he meant the US government deliberately decided to support extremist groups and the founding of a Salafist principality, Flynn stood firm and said “it was a willful decision to do what they’re doing.”11

Comment: These very statements strongly suggest, according to those who want regime change and war in Syria, why Flynn had to be ejected from the Trump administration. Michael Flynn not only knew quite a lot about the Frankenstein’s monster that was ISIS, but was set against it and the type of thinking that went into building it. He also expressed actual concern for how much of the American public would react to such information – about how horrible its own government’s actions were. Imagine how such a sentiment by Flynn was received among those in the military and intelligence circles who have been committing their regime change crimes for so many decades: “Who the hell does Flynn think he is?! Get him outta there!!“

Former MI6 agent Alastair Crooke later attempted to shed some light on the strategic thinking behind all of this. He explained that the idea “of breaking up the large Arab states into ethnic and sectarian enclaves” had been “established group think” at least as far back as 2006, and that this idea had been “given new life by the desire to pressure Assad in the wake of the 2011 insurgency launched against the Syrian state.” The idea being to drive “a Sunni ‘wedge’ into the landline linking Iran to Syria”, and thereby fracture the connection between Iran and its Arab allies.12

Following along with much of what Biden, Obama, and others had said about the inability to find moderates and the necessity of relying upon extremists, Crooke concluded that “the jihadification of the Syrian conflict had been a ‘willful’ policy decision, and that since Al Qaeda and the ISIS embryo were the only movements capable of establishing such a Caliphate across Syria and Iraq, then it plainly followed that the U.S. administration, and its allies, tacitly accepted this outcome, in the interests of weakening, or of overthrowing, the Syrian state.”13

A Useful Pretext

Much effort has been made to portray ISIS as antagonistic to US interests and to place blame for its rise on official enemies. This is not surprising given the near-unanimous outrage that the group elicited after emerging on the world stage. However, outside of being a useful ideological construct, this analysis neglects some very fundamental characteristics inherent to the situation.

Apart from the obvious conspiracy theories there is of course evidence that after ISIS was founded in 2014 it had made a sort of compact with Bashar al-Assad’s government. After gaining access to documents of a former deputy to Baghdadi, Der Spiegel uncovered what appeared to be an agreement between ISIS and Syria’s Ba’ath regime. The nature of the agreement was an understanding that Syria’s air force would not strike ISIS and in return ISIS commanders promised to order their fighters not to fire on Syrian army soldiers. This made sense for ISIS since its immediate goal was to gain supremacy over Sunni areas while the Syrian army was, as well, primarily concentrated on the immediate threats that it faced from other groups further west. It was in the interests of both sides to avoid a mutually assured destruction with each other.14

The problem with taking this too far is that after ISIS had consolidated its hold over Raqqa and gained supremacy over much of the other rebel groups this understanding appeared to have dissolved, ISIS then mounting an assault against the Syrian army at Al-Tabqa airbase and executing more than 160 Syrian soldiers. Since that point, ISIS has been in a constant state of war with the Syrian army, despite many attempts by regime-change supporters to claim otherwise.15

These kinds of arguments seem to miss an even larger aspect of the bigger picture and misinterpret the motivation of the various players involved. A truer picture of the situation is perhaps best exemplified by the dilemma that faced the Western powers as the public became increasingly aware of ISIS’ atrocities and began calling for some kind of a response to be made against the group. As Western officials had portrayed ISIS as a grave threat to Western civilization, there was great pressure on them to put their money where their mouth was and act. However, this put them in an awkward position.

For one thing, in terms of breaking up an enemy state into sectarian enclaves, ISIS had indeed proven quite efficient. It was also emerging as the strongest opponent to Assad and had accomplished much in the way of weakening the Syrian state, while, as well, driving an effective ‘Sunni wedge’ between Iran and its’ allies. Problematically then, as Christopher Davidson explains, “the Islamic State was effectively on the same side as the West, especially in Syria, and in all its other warzones was certainly in the same camp as the West’s regional allies.” Moreover, “on a strategic level, its big gains had made it by far the best battlefield asset to those who sought the permanent dismemberment of Syria and the removal of Nouri Maliki in Iraq.”

The trick, therefore, was “trying to find the right balance between being seen to take action but yet still allowing the Islamic State to prosper.”16

The response was an airstrike campaign aimed primarily at delineating boundaries that the group was not allowed to cross, mainly around the US’ own allies. This campaign also served as a useful opportunity to establish a military presence in Syria which otherwise would not have been manageable. After all, who would object to such an operation when it was being targeted against such a horrific barbarity as the Islamic State?

After having done nothing to stop the previous sectarian massacres that ISIS had committed, the US decided to launch its’ campaign when it appeared that the Yazidi’s in Iraq were about to face an imminent genocide at the hands of the advancing jihadists. While the mission was portrayed as a selfless rescue mission necessary to break a debilitating siege that ISIS had inflicted upon the Yazidis, in reality Kurdish fighters had already arrived on the scene days before the US got there and had begun the process of evacuating the civilians from the area.17

The real reason the US launched the mission was because ISIS was advancing towards the nearby Kurdish capital of Irbil which represents a key US client and area of extraction for Western energy companies. Apart from Western oil interests being heavily invested in the exploitation of the area’s natural resources, it also houses Israeli and US intelligence and military operatives conducting anti-Syrian, anti-Iranian, and other regional operations.18 Yet the main strategic purpose of this US alliance with Iraqi Kurdistan has been to make sure that the regime in Baghdad stayed in line; one CIA memorandum stating that the Iraqi Kurds are a “uniquely useful tool for weakening Iraq’s potential”, as well as a “card to play” against the Iraqi state.19

Therefore, far removed from the very public displays of humanitarian concern, Obama explained that the US would “take action if [ISIS] threatens our facilities anywhere in Iraq… including Irbil”, and made good on his promise that airstrikes would be launched “should they move toward” the Kurdish capital.20

The analogous delineation of boundaries in Syria occurred a few months later when the US launched airstrikes to help defend the Kurdish enclave of Kobane from a similar assault by the Islamic State, the Syrian Kurds fast becoming a useful US ally on the ground. A highly-publicized spectacle, these airstrikes helped to solidify the legitimacy of the illegal bombing campaign. However, it was never apparent how crucial the US’ assistance actually was, or if the bulk of the city’s defense hadn’t already been secured by the towns battle-hardened fighters.21

Nevertheless, these pretexts proved useful. In one sense, they allowed the West to appear responsive to public demands for action, while, at the same time, allowing Western aircraft to conduct a de-facto no-fly-zone over ISIS territory in Syria. There was a real danger that states genuinely committed to the protection of the Syrian government, notably Iran but possibly Russia, would take matters into their own hands and actually try to eradicate the Islamic State. In this sense, the US-led campaign was useful in portraying the image of US commitment to defeating ISIS while insuring, as well, that no other state would defeat the group before their use had been exhausted and the West could claim that symbolic victory for themselves.22

Notes here

The Purpose of ISIS

Awkwardly for those at the helm of the US-led bombing campaign, as time went on it became increasingly apparent that not only was the Islamic State not being “degraded and destroyed”, but, in fact, was growing and taking control of even more territory. This was further compounded by the groups’ relatively weak military capabilities, and the fact that the areas they occupied consisted mainly of open countryside with relatively few areas to hide their equipment and convoys.1 US war veterans have even remarked that the US could have turned the tide against the organization using only aircrafts from the WWII-era, while other academics explain that “an international force could defeat ISIS in a matter of months” if they wanted to.2 Despite all of this, after months of airstrikes, the Wall Street Journal noted that the US had “failed to prevent the Islamic State from expanding its control in Syria”, while the British press explained that “in both Syria and Iraq, Isis is expanding its control rather than contracting.”3

In fact, while the Pentagon paraded around statistics of killed ISIS fighters to showcase the campaign’s success, in reality by the summer of 2015 the Islamic State had seen a doubling in the number of its foreign fighters, more than replacing any of those claimed to have been killed.4 Maps were similarly published showing ISIS’ territorial losses, yet at the same time evidence showed that its other territorial gains had actually offset any sort of contraction.5 So while US aircraft patrolled the skies around the so-called caliphate, its fighters were more than free to roam throughout the territory they had claimed. Indeed, convoys consisting of upwards of hundreds of vehicles were mainly free to travel in long columns in wide-open desert terrain despite the ease with which such targets could be hit by US aircrafts.6

As this continued, it became increasingly difficult to conceal the truth, especially as Department of Defense analysts began to break ranks and complain that their superiors within senior levels of the intelligence command had deliberately been altering reports, downplaying the campaign’s failures and presenting it in a much more positive light.7 Furthermore, with the introduction of the Russian intervention, the insincerity of the US effort was even more laid bare. Not only had the Russians conducted more sorties against the group in one day than the US had in months, one of their first targets were its oil truck convoys which the US had deliberately refrained from hitting during their entire year-long campaign, despite it being one of the groups’ biggest sources of revenue.8 Awkwardly as well, it was becoming increasingly apparent that US fighter jets were being particularly careful about avoiding engagement whenever ISIS was fighting against US adversaries such as the Syrian army or Hezbollah, a situation which was not lost on the administrations in Tehran and Damascus.9

The motivations underlying all of this were quite clearly articulated by an Iraqi army officer who argued that the “Americans weren’t really that serious in hitting the Islamic State.” Getting even closer to the truth, a commander of a Shia militia fighting in Iraq as well explained “we believe the US does not want to resolve the crisis but rather wants to manage the crisis… it does not want to end the Islamic State. It wants to exploit the Islamic State to achieve its projects in Iraq and in the region.”10

Elaborating on the US’ calculation even further, international correspondent Elijah J. Magnier explained that “as long as ISIS was headed towards creating a serious danger to Assad in Syria”, then its presence could be tolerated. The strategy revolved around maintaining “the organizations continuing ability to fight for as long as necessary in the process [of] depleting Iran, Hezbollah and its Iraqi proxies in Syria… Its continuing presence was needed so as to exhaust Iran and its allies in both Iraq and Syria.”11

One of the more prominent examples of this was when ISIS began to expand its control over territories outside of Syria and led an offensive into Iraq.

The offensive was known to US intelligence long before it was launched. Indeed, far from being indecipherable, the Wall Street Journal explained that such an advance was “apparent to anyone paying attention to Middle Eastern events”, noting that it “wasn’t an intelligence failure. It was a failure by policy makers to act on events that were becoming so obvious that the Iraqis were asking for American help for months… Mr. Obama declined to offer more than token assistance.”12

The reasons for this lie in the continuing shift towards Iran that was being undertaken by then Prime Minister Maliki and the subsequent expansion of Iranian influence over the Iraqi government that resulted. By this time, Maliki had appointed the pro-Iranian Hadi al-Amiri as transport minister, and in doing so “had effectively given Tehran the green light to use Iraqi infrastructure to channel supplies and fighters through the country to fight in Syria.”13 Even more troubling, knowledgeable reports indicated that Maliki’s main objective was to prevent the establishment of any US military bases in the country, following an official request by Iran.14 Therefore, for those committed to toppling the increasingly Iranian-backed Nouri al-Maliki administration, the ISIS offensive represented an important opportunity.

In this sense, the failure of the US to respond was explained by Obama himself. He noted that the US “did not just start taking a bunch of airstrikes all across Iraq as soon as ISIS came in” specifically because “that would have taken pressure off of al-Maliki.”15 Indeed, harkening back to the aforementioned strategy of utilizing radical Sunni’s to pressure and put “fear into the government of Prime Minister Maliki”,16 Obama said that a more forceful US response would have encouraged Maliki to think “We don’t actually have to make compromises. We don’t have to make any decisions. We don’t have to go through the difficult process of figuring out what we’ve done wrong in the past. All we have to do is let the Americans bail us out again. And we can go about business as usual.”17

Therefore, Al Rai newspaper’s Elijah J. Magnier explains that “as long as the aim of ISIS’s military activity and expansion was to occupy land in Iraq, governed by pro-Iranian Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki (creating a weak state and much confusion in the Iraq-Iran relationship)”, then “the ISIS presence in Iraq could be tolerated” by the US.18

The result of this offensive was the unprecedented capture of Mosul, shocking observers worldwide.

Despite having a fighting force of no less than 350,000 battle-hardened soldiers, the Iraqi security forces simply “disintegrated and fled” in the face of roughly 1,300 lightly-armed ISIS jihadists.19 This was later explained by analysts as being the result of corruption within the military, or due to indications that ISIS was welcomed by a significant portion of the population, or that it had in many ways already been operating a shadow government of sorts within the city.20 While indicative, ISIS’ uncontested walk-in to Mosul could have been more directly linked to the desire of outside powers to replace Prime Minister Maliki. Indeed, the Gulf states did little to hide their animosity towards Maliki or their desire to overthrow his regime. As professor Fouad Ajami pointed out, after the US invasion “the Gulf autocracies had hunkered down and done their best to thwart the new Iraqi project” and were hoping to turn Maliki’s Iraq into a “cautionary tale of the folly of unseating even the worst of despots.”21 At least from Maliki’s own perspective, it was Saudi Arabia and Qatar which were the main drivers of his overthrow.22

Whatever the case, it was the pressure exerted on Maliki from the loss of Mosul and the inability to halt the Islamic States’ advances that were the main catalysts which lead to his ouster. According to one Wall Street Journal reporter, “After the rout of the Iraqi military that year, combined pressure from Washington and Tehran led the Iraqi parliament to oust Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, seen in both capitals as responsible for the debacle, and to replace him with current Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi.”23

In this sense, the presence of the Islamic State had served a number of purposes for the outside powers involved within the region. Put in other words, University of Cincinnati professor emeritus Abraham Miller explains that “the Islamic State exists as a political structure whose function outweighs the political and military costs of defeating it, not just for the US but also for the Sunni sheikhdoms of the Persian Gulf.” Functions which include providing “a direct check on the hegemonic interests of Iran to extend its reach from its eastern border into the Levant… The threat they [ISIS] pose is tolerated even by the Gulf sheikdoms as long as ISIS is focused on stopping Iranian hegemony.” Because of this, “Obama has no intention of destroying the Islamic State”, but rather “ISIS is a chain reaction. As long as it is controlled, its chaos is perceived to serve a multiplicity of purposes within and outside the region.”24

Notes here

The Strategic Asset, Then and Now

About a year after the fall of Mosul, ISIS as well overtook the Iraqi city of Ramadi. Afterwards, US intelligence and military officials revealed to Bloomberg that the US had “significant intelligence” about the pending attacking. For the US military, it was an “open secret” at the time, which “surprised no one.” The intelligence community was able to obtain “good warning” that ISIS was planning “a new and bolder offensive in Ramadi” because they had identified “the convoys of heavy artillery, vehicle bombs and reinforcements through overhead imagery and eavesdropping on chatter from local Islamic State commanders.”

Indeed, departing from ISIS’ base in Raqqa, these convoys consisted of long columns of vehicles and had travelled a full five-hundred and fifty kilometers through open desert in broad daylight to reach Ramadi. Despite this, the US coalition did not act, instead they “watched Islamic State fighters, vehicles and heavy equipment gather on the outskirts of Ramadi before the group retook the city.” The US “did not order airstrikes against the convoy before the battle started”, but instead “left the fighting to Iraqi troops, who ultimately abandoned their positions.”1

Commenting on this, former MI6 agent Alastair Crooke noted that “the images of long columns of ISIS Toyota Land Cruisers, black pennants waving in the wind, making their way from Syria all the way – along empty desert main roads – to Ramadi with not an American aircraft in evidence, certainly needs some explaining.” He continues by pointing out that “there cannot be an easier target imagined than an identified column of vehicles, driving an arterial road, in the middle of a desert.”2

Even more troubling, it seems that the US had taken further precautions to ensure that the Iraqi forces would not be able to repel the ISIS attack. In the same Bloomberg report, US officials revealed that Iraqi government forces in Ramadi were not being properly resupplied, stating that ever since the US-led campaign began they had been forced to acquire weapons and ammunition on the black market since supplies were simply not reaching them.3

After the fall of the city to ISIS, Iraq was thereafter dependent on the US military to help repel the invading forces, which appears to parallel closely with the aforementioned strategy envisioned by think-tank analysts whereby “moderate or even radical Sunnis” could be useful in order to pressure and “put fear” into the government, and thereby help “encourage [them] to cooperate with the US.”4

Explaining further how such situations may be used for the political benefit of outside powers, University of Cincinnati’s Abraham Miller explains that “as long as there is chaos” like that produced by the Islamic State, then “there is a need for foreign intervention” such as the American intervention in Iraq. Such interventions are important opportunities because “with chaos and bloodshed come arm sales and political and economic influence.”5

This seems to track quite closely as well to a strategy envisioned for Iraq during the Bush administration. Co-authored by then Vice President Cheney and other influential neoconservatives, the strategy put particular importance on Washington being able “to justify its long-term and heavy military presence in the region”, which could be accomplished through the Iraqi state being weak and unable to defend itself, and therefore the US military would ostensibly be “necessary for the defense of a young new state asking for US protection.” Yet the real reason for the US presence would be “to secure the stability of oil markets and supplies,” which “in turn would help the United States gain direct control of Iraqi oil and replace Saudi oil in case of conflict with Riyadh.“6

Today much of this has been achieved, Iraq having been forced to ask the US for protection while the chaos and bloodshed justify further arms sales and help to expand political and economic influence over the country.

After the replacement of Maliki, Iraq has largely been secured by the US and rid of a lot of its former Iranian influences.7 Given this, the presence of ISIS now serves as a useful means to further demonstrate Iraq’s dependence on the US military, a dependence the US intends to nurture. In a telling admission, Secretary of State Tillerson confirmed that recent troop deployments would remain in the country after ISIS is defeated, in order to “help clear mines and establish stability.”8 As well, with the elimination of ISIS, Iran would be closed off from the opportunity of expanding its influence through its sponsoring of various proxy militias throughout the country.9

The symbolic victory of a US-backed ISIS defeat would further legitimize the US presence in Iraq and help convey a positive image of the US’ role in the Middle East. Meanwhile, the very recent threat that the Islamic State posed could be invoked in the future if the government in Baghdad ever flirted with closer Iranian ties or strayed too far from the US-designated course. With Trump’s increasingly Pentagon-influenced administration, the current fight against the Islamic State will also be useful in justifying increased arms sales both to the Iraqi forces and for the US jets flying overhead. In this sense, it appears “the political and military costs of defeating” ISIS would outweigh its previous functions.10

In Syria, however, the situation is different. In a revealing interview, the former British Prime Minister argued for Britain to join the US campaign against ISIS on the basis that it was a “direct threat to Britain”, and that he was “not prepared to subcontract the protection of British streets from terrorism to other countries’ air forces.” Analysts commented that such a remark was indicative of a policy among the Western administrations which would not allow other states genuinely allied to the embattled Syrian government to claim victory over ISIS for themselves.11 In this sense, while blocking others from defeating the group the universally accepted consensus of the need to eradicate the Islamic State could be transformed into an effective mandate to occupy and annex Syrian lands. With the attempt to overthrow the government having failed, strategy could shift from support to the opposition towards “defeating ISIS.”

Signaling the adoption of such a strategy, the Trump administration announced that it “accepts” the “political reality… with respect to Assad”, and that “foremost among its priorities” from here on out would be “the defeat of ISIS.”12 In many ways this realization was already understood in the final months of the Obama administration, exemplified by the withdrawal of their demand that “Assad must go” and support instead of a negotiated settlement.13 The plan, however, is not to fully abandon regime-change, but to focus on “ISIS” and then after occupation continue to exert pressure and push for Assad’s ouster.

The Partition of Syria

The change in strategy has further become apparent with indications that the CIA has discontinued its covert support for the opposition.14 This represents the failure of the regime-change effort while as well being indicative of the change in political leadership within the White House.

The transition from Obama to Trump represents a long-standing rivalry between the CIA and the Pentagon. During the Obama administration, the Pentagon forcefully opposed the CIA rebel program on the very realistic grounds that it was empowering Islamist extremists, even going so far as to leak military intelligence in order to subvert the operations’ success.15 However, the sectors of power that Obama represented largely centered around the CIA and NSA intelligence apparatus and therefore the program had continued. The Trump administration however largely represents the interests of weapons manufacturers, defense contractors, and the military industrial complex as a whole and is centered around the political leadership of the military and the Pentagon. The public displays of liberal antagonism to Trump are largely a reflection of this internal power-struggle, as are the administration’s efforts to consolidate control over the intelligence agencies and to increase the discretionary powers of the military establishment.

Under Trump the military’s influence over foreign policy has vastly increased, the Defense Secretary being granted leave to authorize deployments and operations with little oversight from the chief executive.16 The result of this has been an increase in the power of the vested interests behind the military industrial base and their ability to steer the course and direction of US foreign policy strategy. The main consequence being the specific character that US imperialism will take, a shift from secretive drone strikes, covert regime-change operations, and the financing of extremist elements towards a strategy of direct military deployment and the securing of foreign-policy interests through overt military operations.17

Thus, the CIA rebel-sponsoring program under Trump has ceased while the footprint of the US military in Syria has grown,18 and the beginning indications of a military occupation have started to become visible.

The Wall Street Journal recently reported that “there is growing receptiveness among US and international officials to the idea of setting up unofficial Syria safe zones.” The nature of these “safe-zones” was described by the French Foreign Minister, who hypothesized “they would cover areas retaken from the Islamic State and help people return to their homes.” However, the plan is for US troops to stay in the region long after ISIS is defeated, US Central Command Army General Joseph Votel announcing that US forces will be “required” to stabilize the region and assist “America’s allies” on the ground for the foreseeable future. The zones would therefore consist of Syrian lands directly under the security control of the US military and their partners on the ground, Secretary of State Tillerson describing them as “interim zones of stability” which would “allow refugees to return home”, wherein the coalition would “help to restore water and electricity” and other vital infrastructure, authority over which is necessary for political control.19

In many ways, this strategy is not new, and was considered as a “plan B” of sorts by planners during the Obama administration.

Exemplifying this mindset, Henry Kissinger had earlier put forward proposals which justified the annexation of Syrian lands under the pretext of defeating ISIS. “In a choice among strategies”, he writes, “it is preferable for ISIS-held territory to be reconquered either by moderate Sunni forces or outside powers than by Iranian jihadists or imperial forces.” The strategy called for the post-Islamic State areas to be put under the direct political control of US allies, who, of course, have been heavily invested in the overthrow of the Syrian state: “The reconquered territories should be restored to the local Sunni rule that existed there before the disintegration of both Iraqi and Syrian sovereignty. The sovereign states of the Arabian Peninsula, as well as Egypt and Jordan, should play a principal role in that evolution.” Turkey, as well, “could contribute creatively to such a process.”

The plan then called for a partition of Syria between these newly annexed entities and the areas still under Syrian government control: “As the terrorist region is being dismantled and brought under nonradical political control, the future of the Syrian state should be dealt with concurrently. A federal structure could then be built between the Alawite and Sunni portions.”20

In many ways, recent US maneuvers have shown that this is, in fact, the course of action being pursued.

The US military has long been setting up key infrastructure such as numerous military bases and an airport within the semi-autonomous Kurdish regions in Syria where hundreds of its special forces maintain a military presence; an indication of long-term plans to remain and establish autonomous regions within the country which the Syrian government would be prevented from reclaiming.21 As well, the US has recently conducted an unprecedented military operation involving hundreds of US soldiers aimed at reclaiming the Tabqa dam from the Islamic State, which is described by the New York Times as an vitally “important power source for north Syria.” The operation is understood to be a precursor to the launching of an offensive against ISIS’ de-facto capital of Raqqa in a final push to eliminate the group.22

The main consequence of the maneuver however has been to block the advance of the Syrian army and Russian air force, preventing them from moving onwards toward Raqqa and claiming victory over ISIS for themselves, harkening back to the strategy invoked by the West of being unwilling to “subcontract the protection of [its] streets from terrorism to other countries’ air forces.”23 International correspondent Elijah J. Magnier explains this operation represents the drawing of a line “of the new ‘safe zone’ that will be occupied by the US forces and will therefore be their future ‘safe haven’, thus beginning the partition of the north of Syria.”24

This paves the way for the split-up of the country into three separate zones of influence, a pro-US Kurdish northeast, a Syrian government controlled west and south, and likely a Turkish-occupied northwest.

The conquest of ISIS’ main capital by US-backed forces would allow Trump to gain a useful “symbolic victory” that will increase his domestic political standing, especially after justifying much of his administrations military build-up under the pretext of fighting extremist groups.25 The increased US military involvement will legitimize further arms sales for domestic weapons industries. As well, the strategy could see the US pushing ISIS towards cities controlled by the Syrian army, thereby keeping the pressure on Russia and Iran as they go about the partition of the country. Most importantly, the US will likely be able to ensure that any pipeline project aimed at directly connecting Iranian gas to European markets would be stymied and unable to pass through Syrian lands, especially those under their control, thus protecting such markets for Western corporations.26

All of this ensures that Syria remains a weakened state which the West will be able to exert significant influence over. After ISIS is dealt with and balkanization is accomplished the subsequent land and leverage gained can be utilized to continue the process of removing Assad from power. According to Tillerson, “The process by which Assad would leave is something that I think requires an international community effort—both to first defeat ISIS within Syria, to stabilize the Syrian country, to avoid further civil war, and then to work collectively with our partners around the world through a political process that would lead to Assad leaving.”27

In this way, the threat of ISIS continues to serve its intended purpose of securing Western corporate and investor control over important consumer markets and valuable Middle Eastern energy resources. ISIS therefore representing the “gift that keeps on giving”,28 which continues to proliferate the interests of the Western powers and their strategic attempts for hegemony over the Middle East.

Those killed in the process outweighed by the “function” represented in the “political structure” of the Islamic State, as professor Abraham Miller describes, whose proliferation of “chaos is perceived to serve a multiplicity of purposes within and outside the region”,29 as can be seen in the recent maneuvers ostensibly aimed at the disintegration of the group.

Originally published on 2017-04-06

Author: Steve Chovanec

Source: Signs of the Times

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS