Views: 2203

The armed conflict between the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and Serbian forces started in 1992 with the KLA attacks on Serbian police officers, non-Albanians that lived in Kosovo and Albanians loyal to Serbia (Johnstone, 2002; Kozyris, 1999). This low level conflict escalated in 1996 with the KLA attacking refugee camps as well as other civilians and policemen resulting in dozens of innocent deaths (Johnstone, 2002; Kozyris, 1999). At this point of time and all up to late 1998, the KLA was regarded as a terrorist organisation (Gelbard, cited in Parenti, 2000:99; Jatras, 2002; Johnstone, 2002; Kepruner, 2003; Rubin, cited in BBC).

Following the collapse of communism in Albania and this country falling into anarchy, many army storage facilities were ransacked and truckloads of weapons were smuggled into neighbouring Kosovo. Increased criminal activities such as drugs and people trafficking as well as compulsory taxing of Albanians working abroad also provided funding for the KLA (Antic, 1999; Jatras, 2002).

Increased KLA terrorist activities were met with a harsh response by the Serbian police and army resulting in some civilian deaths and displacement. Consequent UN resolutions 1160, 1199 and 1203 as well as the Holbrook-Milosevic agreement in 1998 (Littman, 1999) demanded Serbian forces reduce in numbers and withdrawal to pre-conflict positions. Serbian government complied with most of these demands, but the demands were not met fully because of several reasons. The KLA was not disarmed and did not comply with resolutions and increased their terrorist activities. The KLA was constantly provoking Serbian forces, purposely endangering civilians (Thaci, cited in BBC, -) as they knew that “the more civilians were killed, the chances of international interventions were bigger…” (Gorani, cited in BBC, -).

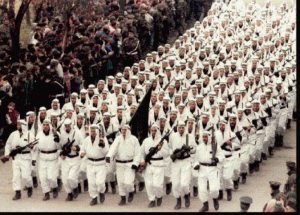

They also re-occupied positions Serbian forces were previously holding  and at some points of time controlled up to 40 % of Kosovo territory. The KLA was re-enforced by hundreds of mercenaries and mujahideens, and started receiving support from the CIA, DIA, MI6 and German Intelligence BND (Bowman, 1999: 8; Marsden, 1999; Chossudovsky, 2001; GN TV, 2005: 1; WSWS 1999).

and at some points of time controlled up to 40 % of Kosovo territory. The KLA was re-enforced by hundreds of mercenaries and mujahideens, and started receiving support from the CIA, DIA, MI6 and German Intelligence BND (Bowman, 1999: 8; Marsden, 1999; Chossudovsky, 2001; GN TV, 2005: 1; WSWS 1999).

The KLA was also supported by Osama Bin Laden and Al Qaeda (Chossudovsky, 2001; Deliso, 2001; GN TV, 2005: 1; Johnstone, 2002:11). Even though the KLA did not comply with UN resolutions and the Holbrook-Milosevic agreement, and it was responsible for most breaches of ceasefire (Robertson, cited in Chomsky, 2004: 56) there was a significant reduction in hostilities and almost all refugees returned to their places of living (Bowman, 1999; Littman, 1999).

The most significant event occurred on January 15, 1999 with the alleged Racak massacre which was wrongly but consciously attributed to Serbian forces by William Walker, the head of the Kosovo Verification Mission who was previously involved in the cover up of atrocities in El Salvador (Bowman, 1999; Berliner Zeitung, cited in Free Republic, 2000; Chomsky, 2004: 56; Fleming, 1999; Gowans, 2001; Johnstone, 2002:239; Parenti, 2000:104; Wilcoxson, 2006).

Allegations that Serbian forces massacred 45 innocent men, women and children were dismissed by Serbian, Belarus and Finnish forensic experts who found that these people have not been massacred or killed from close range as well as that most of them had traces of gunpowder residue on their hands, confirming that they actually were KLA fighters.

The reports also state there was only one woman and one adolescent boy among the dead as well as that only one person was possibly but not explicitly shot from a close range (Berliner Zeitung, cited in Free Republic, 2000; Fleming, 1999; Johnstone, 2002). Even though this was a crucial document, the report was not made public immediately (Berliner Zeitung, cited in Free Republic, 2000; Johnson, 2002).

This was followed by Rambouillet negotiations, which was actually an ultimatum, that the Yugoslav government, or any other government, could not accept (Bennis, 2004: 240-241; Fraser, cited in SBS, 2000; Johnson, 2002: 245-247; Littman, 1999; Miller, 2003: 243; Muller, 1999; Parenti, 2000: 108-114; Pugh, 2001; Trifkovic, 1999). After this the Kosovo Verification Mission was withdrawn and NATO humanitarian intervention or rather aggression began and lasted 78 days.

Numerous scholars (Mertus, 1999; Muenzel, 1999; Power, 2003; Stephen 2004; Urquhart, 2002; Williams, 2003; Young, 2003 and others), International Commission on Kosovo (cited in Neier, 2001:34) and politicians, especially those coming from the NATO countries, who advocate that NATO intervention is justified on the grounds of preventing ethnic cleansing, genocide and even new holocaust as well as securing peace and stability in the region. They base their arguments on the United Nations Chapter VII, the humanitarian international law and the Universal Declaration of Human rights. Falk (cited in Chossudovsky, 2003:1) states that:

The Kosovo War was a just war because it was undertaken to avoid likely instance of “ethnic cleansing” undertaken by the Serb leadership of former Yugoslavia… It was a just war despite being illegally undertaken without authorization by the United Nations, and despite being waged in a manner that unduly caused Kosovar and Serbian civilian casualties while minimizing the risk of death or injury on the NATO side.

However, many other scholars advocate and demonstrate NATO intervention was illegal and unnecessary. According to William Rockler (cited in Chossudovsky, 2003:1), former prosecutor of the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal:

The [1999] bombing war violates and shreds the basic provisions of the United Nations Charter and other conventions and treaties; the attack on Yugoslavia constitutes the most brazen international aggression since the Nazis attacked Poland to prevent “Polish atrocities” against Germans. The United States has discarded pretensions to international legality and decency, and embarked on a course of raw imperialism run amok.

The NATO intervention was illegal as NATO action was unilateral, avoided Security Council and therefore it was in violation of several provisions of the UN Charter, specifically Article 2 (3), Article 2 (4) and Article 53 as well as it breached NATO Charter First Article (Bisset, 2002). The Rambouillet negotiations also breached Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969) Section 2: Invalidity of Treaties Article 51 and Article 51 (Hatchett, 1999).

NATO officials insisted that this is a humanitarian intervention, but Lt. Gen. Mike Short, Commander of Allied Forces, admitted that NATO intervention was actually a war against Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (BBC, -):

I certainly acknowledge that there were people within Allied that felt we weren’t at war, but as commander … in my mind I was at war and people under my control were, and that’s how we had to do our business…

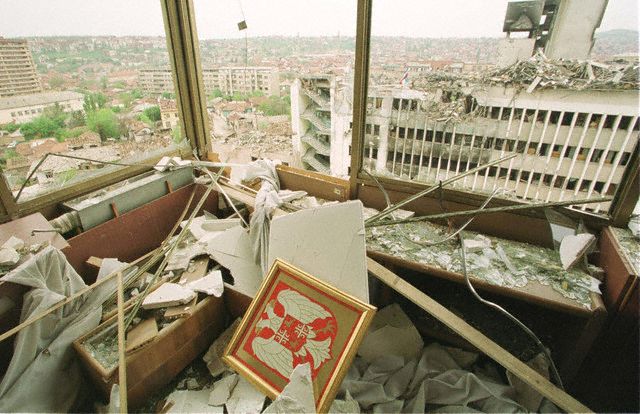

As this was an undeclared war, it also breached Constitutions of NATO countries involved and Geneva Convention Article 52.2. NATO breached this Article numerous times and committed war crimes by bombing schools, hospitals, TV and radio installations, bridges, factories, civilian suburbs of many cities, water treatment and electricity facilities, and deliberately targeting civilians such as in the case of Grdelica train and convoy of Albanian refugees near Djakovica when 75-100 refugees were killed (Bennis, 2004; Savich, 2007; Shen, 1999). Additionally, Captain Adolfo Luis Martin de la Hoz (cited in Morales, 1999), Spanish pilot engaged in NATO aggression, admitted that NATO was deliberately targeting the civilian population. According to the BBC (-) this was decided by Havier Solana and Gen. Klaus Nauman without consulting other NATO countries. Hayden (1999) states that this was a deliberate act:

The Wall Street Journal reported on April 27 that NATO had decided to attack “political, rather than just military, targets in Serbia.” On April 25, the Washington Times reported that NATO planned to hit “power generation plants and water systems, taking the war directly to civilians.”

NATO also breached the Geneva Convention trying to assassinate President Milosevic by bombing his private residence (Guardian, 1999; Malic, 2003) as well as bombing the Chinese embassy.

Moreover, Littman (1999: 8) states

“It cannot be said that the use of force is necessary unless it can be clearly demonstrated that all measures short of force (and in particular measures of diplomacy) have been exhausted.”

The Rambouillet negotiations fall very short of Littman’s statement. The Yugoslav government accepted all political provisions of the agreement and was ready to negotiate on the military part of the agreement. However, NATO’s ‘Appendix B’ of the agreement was presented to the Yugoslav delegation one day before the final date as a non-negotiable agreement. This meant NATO de-facto occupation of Yugoslavia and therefore could not be accepted, however the Yugoslav government was ready to further negotiate military proposals. To prove this, Yugoslav officials (23 February 1999) as well as the Serbian Assembly resolution (23 March 1999) declared that Yugoslavia would accept international force under the UN command (Littman, 1999). However, NATO demanded full compliance with the military part of the Rambouillet agreement and according to senior US State Department official (Kenney, cited in Hatchett, 1999:1) “the United States ‘deliberately set the bar higher than the Serbs could accept.’ The Serbs needed, according to the official, a little bombing to see reason.” Dr Kissinger (cited in Littman, 2004:5) clearly states that:

The Rambouillet text, which called on Serbia to admit NATO troops throughout Yugoslavia, was a provocation, an excuse to start bombing. Rambouillet is not a document that an angelic Serb could have accepted. It was a terrible diplomatic document that should never have been presented in that form.

Furthermore, many scholars and politicians regarded Serbs as perpetrators engaged in ethnic cleansing and genocide. Certainly, there were atrocities including murder, looting and taking revenge on innocent civilians committed by Serbian paratroops and petty criminals. However, these atrocities were not supported by the Yugoslav government and were nothing even close to what NATO and media were reporting (Johnstone, 2002; Mitchell, 1999; Parenti, 2000). The UN Secretary General reported to the UN on 17 March 1999 that situation in Kosovo is characterised by constant and persistent KLA attacks and disproportionate use of force by Yugoslav authorities (Littman, 2004). Kosovo Verification Mission report also states that during the period (Littman, 2004:5) …

22 January and 22 March 1999, passed on by NATO to the UN, show that in this period the total fatalities were 27 for the Serbs and 30 for the Kosovo Albanians. Another estimate puts the total Albanian fatalities over five months from 16 October 1998 to 20 March 1999) at 46; an average of 2 a week. By contrast, in 11 weeks of the NATO war from 25 March 1999 to 10 June 1999 NATO killed 1500 civilians and wounded 8000. This is an average of 136 deaths a week and 30 times as many deaths as the total prior to the war.

Prior to the NATO intervention there were approximately 100,000 refugees on all sides, however after the bombing started this number very quickly escalated to more than 800,000 with 100,000 Serbians, Albanians and others moving into Central Serbia. The question here is did Serbs ethnically ‘cleanse’ their own people from Kosovo? The simple truth is most of the refugees left because of the NATO bombing and increased fighting between the KLA and Serb forces. Lt. Gen. Satish Nambier (1999:2), the Force Commander and Head of Mission of the United Nations Forces in the former Yugoslavia, also acknowledges that there was no intention by Yugoslavs to ethnically cleanse Kosovo. Similarly, Lord Carrington (cited in Littman, 2004:8) declared that:

I think what NATO did by bombing Serbia actually precipitated the exodus of the Kosovo Albanians into Macedonia and Montenegro. I think the bombing did cause the ethnic cleansing… NATO’s action in Kosovo was mistaken… what we did made things much worse.

The testimony of Jacques Prod’homme (cited in Rouleau, 1999), a French member of the OSCE observer mission about period before NATO intervention “during which he moved freely throughout the Pec region, neither he nor his colleagues observed anything that could be described as systematic persecution, either collective or individual murders, burning of houses or deportations.”

Also, there were reports that Serbian forces had plans to clear entire Kosovo of Albanian population by engaging in ‘Operation Horseshoe’ which later proved to be German Intelligence propaganda (Littman, 2004; WSWS, 1999). Other allegations of mass murder of Kosovo Albanians include the US State Department Ambassador Scheffer’s claims (cited in Parenti, 2000) that up to 225,000 Kosovo Albanians aged 14 to 59 were not unaccounted as well as British Foreign Office Minister Hoon claim that in more than 100 massacres more than 10,000 people were killed by Serbian forces. Also, there were allegations that Serbian forces used Trepca mineshafts to dispose bodies of killed Albanians as well burning Albanian bodies in furnaces.

All these allegations were later dismissed as nonsense and NATO propaganda by FBI, French and Spanish forensic experts (Parenti, 2000). The Wall Street journal (cited in Parenti, 2000) reported that by November 1999 about 2,100 bodies were found and these include those killed by Serbian forces, the KLA, NATO bombs and those who died of natural causes. In fact one of the largest mass graves, found near town of Malisevo, contained 24 Serb and non-Albanian bodies mutilated by the KLA (BBC, CNN, Reuters, cited in ERP KIM, 2005)

Finally, the human, economic and environmental costs of NATO aggression were enormous. The total estimate of human losses in FR Yugoslavia, excluding Kosovo, is 2500 with 557 civilians killed and 12,500 wounded (Dedeic, 2007). The total economic costs include £2.5bn direct NATO costs (BBC, 1999) and somewhere between $30 billion and $100 billion costs to Yugoslav devastated economy and infrastructure (Dedeic, 2007).

Environmental costs are not possible to estimate. For instance, NATO planes deliberately targeted chemical complexes in Pancevo causing approximately 100,000 tonnes of highly toxic and cancerogenic chemicals and 8 tonnes of mercury contaminating the air, soil, underground waters as well as the largest river Danube (Djuric, 2005). In Novi Sad, NATO destroyed 150 oil tanks causing more than 120,000 tonnes of oil derivates burning for days and spilling into underground waters and Danube. In Kragujevac and Bor NATO destroyed electricity sub-stations causing more than 50 tonnes of highly toxic dioxin contaminate large areas (Djuric, 2005). In Kosovo and Southern Serbia several areas were repeatedly bombarded with ammunitions containing depleted uranium. Some estimates suggest that more than 10 tonnes of depleted uranium was dumped onto Yugoslavia. Srbljak reported in early 2005 (cited in Djuric, 2005:4) that the rate of people suffering from cancers of lung, bones, liver and other organs were in some parts of Kosovo up 120 times higher than in the same period in 2004.

Overall, NATO ‘humanitarian’ intervention was not at all about humanitarian issues. This was an illegal aggression and an undeclared war against sovereign state of Yugoslavia and violation of the UN Charter and Geneva Convention. NATO intervention caused much greater suffering of all civilians, it devastated environment of Yugoslavia and surrounding countries as well as Yugoslav economy and infrastructure. It also increased antagonism between Kosovo Albanians and Serbs and other non-Albanians minimising chances of coexistence. This was proved by the exodus of 250,000 refugees after NATO occupied Kosovo and Albanian refugees and the KLA returned to Kosovo. It also caused radical Muslim ideas spreading into other parts of former Yugoslavia and further destabilising Sandzak, Southern Serbia and Macedonia. Russia also became concerned with NATO’s action and it increased their military spending thus re-starting arm race.

The actual reasons for NATO aggression are hard to establish. Many authors believe that this intervention was about establishing a new role and the credibility of NATO in the post-Cold War era. Others see this as the result of US imperialism and hegemony as well as economic expansion as Fleming (1999) states “one way to open the market is to concur it”. Some authors also believe that this is a part of the US strategic expansionism towards the East, which involved decade’s long fight against communism and attempts to minimise Russian influence in the world. Yugoslavia was the only country in Europe that was at the time still under communist rule and therefore under Russian influence.

There are certainly those who genuinely believe that NATO intervention was done because of a just cause, thus attempting to prevent humanitarian catastrophe in the middle of Europe. However, their understanding of the whole situation was distorted by the KLA/NATO sophisticated propaganda, media frenzy and the lack of full understanding of the situation on the ground.

Sources

Antic, O. 1999. “Kosovar Independence”: Muenzel’s Biased Pro-Greater Albania Approach. Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from: http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/antic.htm

BBC. – . Exact date and tittle of the TV documentary unknown. (TV documentary about Rambouillet negotiations and NATO intervention in Kosovo)

BBC News. 1999. World: Europe Kosovo war cost £30bn. Retrieved on 02.04.2007 from:http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/talking_point/europewide_debate/329370.stm

Beloni, R. 2002. Kosovo and beyond: Is humanitarian intervention transforming international society? Retrieved on 25.03.2007 from: http://www.du.edu/gsis/hrhw/volumes/2002/2-1/belloni2-1.pdf

Bennis, P. 2004. Calling the shots: How Washington dominates today’s UN. Arriss Books, Gloucestershire.

Bisset, J. 2002. Anniversary of shame: March 1999 – March 2002. Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from:

Bowman, R. M. 1999. Chronology of the conflict in Kosovo. Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from: http://www.rmbowman.com/isss/kosovo.htm

Chomsky, N. 2004. Hegemony or survival: America’s quest for global dominance. Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW.

Chomsky, 2006. Failed states: The abuse of power and the assault on democracy. Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW.

Coady, C.A.J. 2003. War for humanity: a critique. In Ethics and foreign intervention. Eds. D.K. Chatterjee & D.E. Scheid, Cambridge University Press, pp. 274-295.

Chossudovsky, M. 2001. “Osamagate” [sic.]. Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from:http://www.globalresearch.ca/articles/CHO110A.html

Chossudovsky, M. 2001. The Just War theory. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from:

http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=viewArticle&code=CHO20050717&articleId=698

Chossudovsky, M. 2001. NATO and US Government War Crimes in Yugoslavia. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from:http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=viewArticle&code=MIC20020219&articleId=370

Dedeic, S. 2007. Danas se navrsava osam godina od pocetka bombardovanja SR Jugoslavije. Retrieved on 02.04.2007:

http://www.mail-archive.com/sim@antic.org/msg34493.html

Deliso, C. 2001. Bin Laden, Iran and the KLA: How Islamic terrorism took root in Albania. Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from:http://www.antiwar.com/orig/deliso5.html

Durch, J. W. 1997. Introduction to anarchy: Humanitarian intervention and “State building” in Somalia. In UN: Peacekeeping, American policy and the uncivil wars of the 1990s, ed. William J. Durch. MacMillan Press, London, pp. 311-365.

Djuric, V. 2005. Istina koja opominje. Retrieved on 02.04.2007. from: http://arhiva.glas-javnosti.co.yu/arhiva/2005/12/12/srpski/nato2.shtml

ERP KIM Info Service. 2005. Another mass grave with Serb bodies found in Kosovo. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://www.decani.org/news/archive/2005/May_15/1.html

Free Republic, 2000. “Berliner Zeitung” disputes massacre claims: Racak a hoax. Retrieved on 31.03.2007 from:http://www.freerepublic.com/forum/a39bac263741e.htm

Fleming, T. 1999. Serbian Studies Foundation Forum – Macquarie University. Personal encounter on 09.05.1999.

German Network TV (GN TV). 2005. German Intelligence and the CIA supported Al Qaeda sponsored Terrorists in Yugoslavia. Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from: http://www.globalresearch.ca/articles/BEH502A.html

Gowans, S. 2001. Sorting through the lies of the Racak massacre and other myths of Kosovo. Retrieved on 31.03.2007 from:http://www.mediamonitors.net/gowans1.html

Guardian. 2002. Ground troops ‘may go in within four weeks’. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/Kosovo/Story/0,,206951,00.html

Hapmson, F.O. 1997. ‘The Pursuit of human rights: The United Nations in El Salvador’. In UN: Peacekeeping, American policy and the uncivil wars of the 1990s, ed. William J. Durch. MacMillan Press, London, pp. 68-102.

Hatchett, R.L. 1999. Serbs had little choice: Kosovo peace accord not what we think. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from:http://www.srpska-mreza.com/Kosovo/NATO-attack/Rambouillet.html

Hayden, R. 1999. Humanitarian Hypocrisy. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/hayden.htm

Jatras, S.L. 2002. The crimes of the KLA: Who will pay? Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from:http://www.antiwar.com/orig/jatras9.html

Johnstone, D. 2002. Fool’s crusade: Yugoslavia, NATO and Western delusions. Monthly Review Press, New York.

Kepruner, K. 2003. Putovanja u zemlju ratova: Dozivljaji jednog stranca u Yugoslaviji, book review by Carl Savich. Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from: http://www.serbianna.com/columns/savich/069.shtml

Kozyris, P.J. 1999. Delayed learning from Kosovo: Any chance of common understanding of facts and law. Retrieved on 28.03.2007 from: http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/phaed1.htm

Krasno, J.E. & Sutterlin, J.S. 2003. The United Nations and Iraq: Defanging the viper. Praeger Publishers, Connecticut.

Littman, M. (QC). 1999. Kosovo: law & diplomacy. Retrieved on 28.03.2007 from: http://www.agitprop.org.au/stopnato/20000125littmcpsuk.php

Littman, M. (QC). 2004. Do you remember Kosovo. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from:http://www.barder.com/politics/international/kosovo/littman2.php

Malic, N. 2003. Citizen Clark? Or, why electing a mass murderer is a really bad idea. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from:http://www.antiwar.com/malic/m091803.html

Mertus, J. 1999. Kosovo & Yugoslavia: Law in crisis. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/acad-op.htm#Jules

Miller, R.W. 2003. ‘Respectable oppressors, hypocritical liberators: morality, intervention, and reality’. In Ethics and foreign intervention. Eds. D.K. Chatterjee & D.E. Scheid, Cambridge University Press, pp. 215-250.

Mitchell, A. Serbian Studies Foundation Forum – Macquarie University. Personal encounter on 09.05.1999.

Morales, J.L. 1999. Spanish pilot admits NATO attacked civilians. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://www.balkan-archive.org.yu/kosovo_crisis/Jun_16/5.html

Muenzel, F. 1999. “What does Public International Law have to say about Kosovar independence?” Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/simop.htm

Muller, R.F. 1999. Serbian Studies Foundation Forum – Macquarie University. Personal encounter on 09.05.1999.

Neier, A. ‘The quest for justice’, The New York Review of Books (8 March 2001), pp. 31-35.

Parenti, M. 2000. To kill a nation: The attack on Yugoslavia. Verso, London.

Posner, E.A. 2006. The humanitarian war myth. Retrieved on 27.03.2007 from:http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2006/09/29/AR2006092901435.html

Power, S. ‘Conclusion’. In ‘A problem from hell’: America and the Age of Genocide. Flamingo, London, pp. 503-516

Pugh, M. ‘Peacekeeping and humanitarian intervention’. In Brian White, Richard Little and Michael Smith (eds.) Issues in world politics. Palgrave, Basingstoke, 2001, pp. 113-131

Rouleau, J. 1991. French diplomacy adrift in Kosovo. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://mondediplo.com/1999/12/04rouleau

Savich, C. 2007. Anatomy of NATO war crimes: The Grdelica passenger train bombing. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from:http://www.serbianna.com/columns/savich/088.shtml

Satish, N. Lt. Gen. 1999. The fatal flaws underlying NATO’s intervention in Yugoslavia. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from:http://www.sipa.columbia.edu/ece/flaws.pdf

SBS. 2000. Exact tittle of the TV documentary unknown (Malcolm Fraser on CARE Australia involvement in former Yugoslavia).

Shen, J. 1999. A Politicized ICTY Should Come to an End. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/shen.htm

Shinoda, H. 2000. The politics of legitimacy in international relations: The case of NATO’s intervention in Kosovo. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://www.theglobalsite.ac.uk/press/010shinoda.htm

Stephen, C. 2004. Judgement day: The trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Atlantic Books, London.

Stokes, D. 2003. Why the end of Cold War doesn’t matter: the US war of Terror in Columbia. Retrieved on 25.03.2007 from:http://www.chomsky.info/onchomsky/200310–02.pdf

Thomas, R.G.C. 1997. NATO and International Law. Retrieved on 01.004.2004 from: http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/thomas.htm

Trifkovic, S. 1999. Serbian Studies Foundation Forum – Macquarie University. Personal encounter on 09.05.1999.

Urquhart, B. ‘In the name of humanity’. The New York Review of Books (27 April 2000). pp. 19-22.

Urquhart, B. ‘Shameful neglect’. The New York Review of Books (25 April 2002). pp. 11-14.

Wheeler, N.J. & Bellamy, A. J. 2005. Chapter 15 ‘Humanitarian intervention in world politics’. In The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, 3rd ed. Eds. J. Baylis and S. Smiths. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 556-578.

Wilcoxson, A. 2006. The 1999 Racak massacre: KLA had been planning to fabricate “Serbian crimes”. Retrieved on 31.03.2007 from: http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=viewArticle&code=20060127&articleId=1836

Williams, L. ‘Altered States’, The Sydney Morning Herald (22-23 November 2003)

Whitman, J. – . After Kosovo: The Risks and Deficiencies of Unsanctioned Humanitarian Intervention. Retrieved on 01.03.2004 from: http://www.jha.ac/articles/a062.htm

World Socialist Web Site (WSWS). 1999. Why is NATO at war with Yugoslavia? World power, oil and gold. Retrieved on 30.03.2007 from: http://www.wsws.org/articles/1999/may1999/stat-m24.shtml

World Socialist Web Site (WSWS). 1999. “Operation Horseshoe” – propaganda and reality: How NATO propaganda misled public. Retrieved on 01.04.2007 from: http://www.wsws.org/articles/1999/jul1999/hs-j29.shtml

Young, I.M. 2003. Violence against power: critical thoughts on military intervention. In Ethics and foreign intervention. Eds. D.K. Chatterjee & D.E. Scheid, Cambridge University Press, pp. 251-273.

Originally published on 2019-03-14

Author: Dragan Vladić

Source: Global Research

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.