Views: 1459

What was the impact of the 1945 Yalta Conference on Yugoslavia? The key result of the conference for Yugoslavia was that it endorsed and ratified the 1944 agreement between Josip Broz Tito and Ivan Subasic. The end result was that the American, British, and Soviet governments installed a dictatorship in Yugoslavia.

The Allied task was the illusory and chimerical objective of uniting the prewar, monarchist Yugoslav Government-in-Exile based in London headed by Peter II Karadjordjevich with Tito’s de facto anti-monarchist, Soviet-style, Communist government in Belgrade. This was the major issue that was discussed at plenary meetings and foreign ministers sessions at Yalta.

How viable and practicable was the position reached at Yalta on Yugoslavia? Was a unified or coalition government possible in Yugoslavia, uniting a monarchy and an anti-monarchical Communist regime which perceived each other as illegitimate and antithetical? Was it merely a smokescreen? Was it a puppet-show? Was it a hoax or deception intended to placate the public and present a public relations victory?

The impact of the Yalta Agreement on Yugoslavia was that the Three Allies, the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, endorsed and ratified the Josip Broz Tito Communist dictatorship as the recognized government of Yugoslavia.

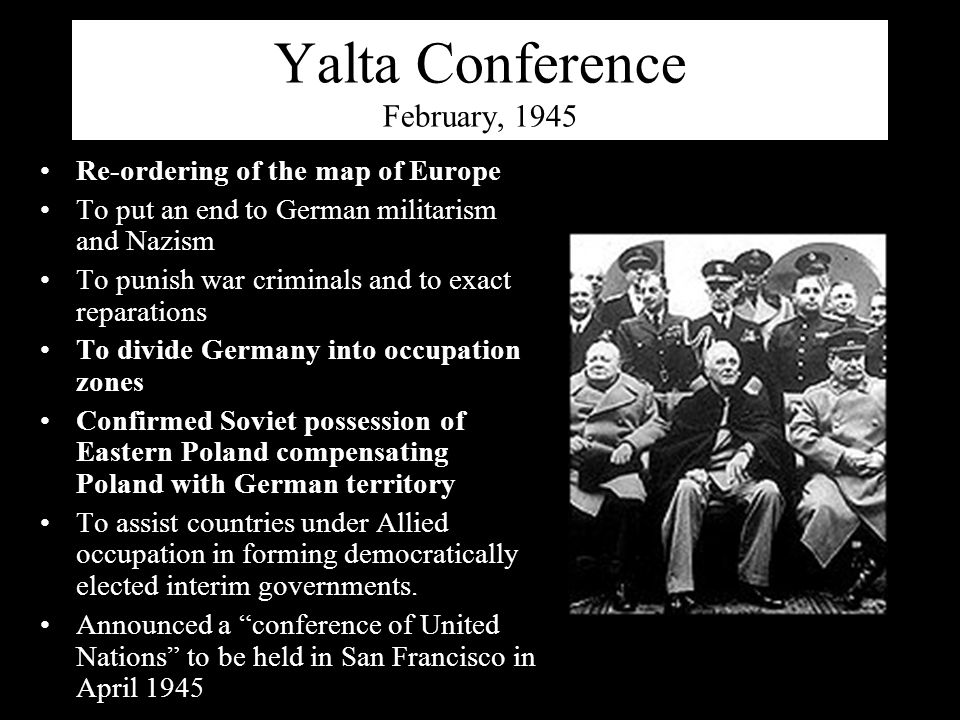

Yalta Conference

From February 4-11, 1945, the leaders of the three main Allied powers met at the Livadia Palace outside the sea-port town of Yalta in southern Crimea to discuss the final stages of the war against Germany and Japan and the postwar world order.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin represented Great Britain, the U.S., and the USSR respectively at the negotiations at the Yalta Conference. At the conference, code-named “Argonaut”, the three leaders finalized plans for the organization of Europe after the expected Allied victory.

The meeting resulted in the decision to accept only the unconditional surrender of Germany and to divide the country and the city of Berlin into four occupation zones. The Allies agreed to German reparations, including the use of forced labor. The Allies agreed to hand over to the Soviet Union all Soviet citizens whether they agreed or not. The Soviet Union agreed to join the United Nations and to allow free elections in Poland. Plans for the establishment of the United Nations were finalized. Finally, it was agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan within 90 days after Germany’s defeat.

Soviet national security interests focused on creating a block of states in Eastern and Central Europe that would prevent the emergence of hostile states along its borders. The goal was to preclude or prevent the emergence of hostile countries along its border which could function as springboards or bases for invasion as occurred in 1941 during Operation Barbarossa when Germany attacked from bases in Poland, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Finland, and the NDH, Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina. This was a primary focus of Soviet foreign policy.

The British pushed for free elections and democratically-elected governments in Eastern and Central Europe. In Poland, the objective was to allow free elections to decide what government would be established there.

The U.S. objective was to induce the Soviet Union to declare war against Japan and to participate in the planned invasion of mainland Japan. The U.S. goal was to minimize American casualties. Another goal was to gain Soviet support and approval for the United Nations, which would be based in the U.S.

The Yalta Conference was lambasted after the war as “another Munich”, “Western betrayal”, and “appeasement”. This was the accepted Cold War ideological perception of the conference. It had been the second of three conferences held during the war between the three major powers, “The Big Three”, with Tehran in November-December, 1943, and Potsdam in July, 1945. The decisions made remain “controversial” and the subject of debate. What actually occurred at Yalta?

One issue that has been ignored is the American role in the establishment of a Communist dictatorship in Yugoslavia.

Yugoslav Impact

The Three Allied Powers imposed or dictated a settlement in Yugoslavia. The Tito-Subasic Agreement was agreed to only after intense British pressure with American and Soviet support. Tito refused to meet with Peter. Subasic had not even gone to Belgrade at the time of the agreement. Peter was not satisfied with key parts of the deal.

The Allied objective was to create a compromise solution which a priori was unrealistic, contradictory, and satisfactory to none of the parties.

The Tito-Subasic Agreements were reached in 1944 and by the time of Yalta were finally accepted and finalized.

There were only two issues that needed to be resolved at Yalta. The British plan focused on creating a decision-making body in Yugoslavia that would not consist solely of Communists or Tito supporters. They also wanted a body that would have oversight on the decisions made. The goals were to have diversity in the legislature and a body that would prevent dictatorial decisions or pronouncements.

The U.S. representative at the conference, Charles E. Bohlen of the State Department, changed the term “NLA” to “Parliament” and to “Constituent Assembly” in the final draft of the protocol. This was to prevent the perception that these were Partisan or Communist-controlled bodies.

The plan consisted of two components.

First, the British and American goal was to expand the NLA or AVNOJ Assembly to include members of the last Yugoslav legislature or Skupshtina in Belgrade, which had been in place in 1941, who had not collaborated. They would be non-Communist, non-Partisan and non-Tito members. The objective was to create plurality and prevent a monopoly by the NLA. This grouping would act as a temporary Parliament.

Second, the British proposed that the legislative acts of this body be ratified by a constituent assembly. FDR supported these amendments, but Stalin and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov opposed them. The latter wanted to put the Tito-Subasic government in power first, before the amendments were ratified.

Stalin subsequently agreed to the amendments, which were published with the communique of the conference and immediately transmitted to Tito and Subasic by telegram. FDR, Stalin, and Churchill agreed on this joint statement on Yugoslavia.

The American Role

American and British leaders knew the facts about Yugoslavia. They knew the nature of the Josip Broz Tito Partisan Movement. They grasped that the goal or objective was to install a Soviet-style Communist dictatorship. Briefing and position papers had been submitted by the parties at the conference. The U.S. State Department assessed the scenarios in Yugoslavia. A special paper was presented on Yugoslavia.

The paper noted that the goal of the Tito regime was to establish a Communist dictatorship: “Frankly, Marshal Tito and his subordinates have not shown a disposition toward cooperation or even common civility in recent weeks. … All indications point to the intention of the Partisans to establish a thoroughly totalitarian regime, in order to maintain themselves in power.”

The U.S. State Department report analyzed the Tito-Subasic Agreement sponsored by Winston Churchill. It concluded that the agreement would “transfer the effective power of government to the Tito organization, with just enough participation of the Government–in-Exile to facilitate recognition by other governments.” Nevertheless, the conclusion was that the language of the agreement was “in line with our ideas” but that “any endorsement of a new administration” should be “contingent on freedom of movement and access to public opinion … for our observers.”

The agreement greatly reduced the role of the monarchy. Peter could not return to power until a “referendum” was held in Yugoslavia to determine whether this was what the populace wanted. A Regency Council would be formed to represent him, appointed by pro-monarchist or Royalist members and Tito’s Council. Peter opposed these measures which minimized the role of the monarchy and which marginalized his power. Nevertheless, the British pushed through the accords which were announced in January, 1945, just weeks before the Yalta meeting.

The Yalta Conference Agreement was announced on February 11, 1945 as a consensus reached at the Crimea Conference in Yalta between U.S. President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin together the members of the United Nations.

They had the unenviable and impossible task of uniting the Yugoslav Government in Exile based in London with Tito’s de facto government in Yugoslavia in Belgrade.

The U.S. policymakers, thus, understood that the Tito-Subasic Agreement was a sham that would allow Tito to assume complete control in Yugoslavia. It was a face-saving measure and window dressing.

Pressure on Peter

In May, 1944, pressure was put on Peter to dismiss Draza Mihailovich as Minister of War. In June, he was forced to dissolve the Bozidar Puric regime, which had been pro-monarchical and anti-Partisan. This set the stage for installing Tito in power in Yugoslavia.

The protocol of the Yalta Conference stipulated:

“The Crimea Conference of the heads of the Governments of the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which took place from Feb. 4 to 11, came to the following conclusions:

VIII. YUGOSLAVIA

It was agreed to recommend to Marshal Tito and to Dr. Ivan Subasitch:

(a) That the Tito-Subasitch agreement should immediately be put into effect and a new government formed on the basis of the agreement.

(b) That as soon as the new Government has been formed it should declare:

(I) That the Anti-Fascist Assembly of the National Liberation (AVNOJ) will be extended to include members of the last Yugoslav Skupstina who have not compromised themselves by collaboration with the enemy, thus forming a body to be known as a temporary Parliament and

(II) That legislative acts passed by the Anti-Fascist Assembly of the National Liberation (AVNOJ) will be subject to subsequent ratification by a Constituent Assembly; and that this statement should be published in the communiqué of the conference.”

There was also a discussion of the post-war borders between Yugoslavia, Italy, and Austria. The Foreign Secretaries debated whether a Yugoslav-Bulgarian pact of alliance was feasible. The issue was whether a country under an “armistice regime” and under military occupation such as Bulgaria could enter into a treaty with another state. Eden expressed the view that an alliance between the Bulgarian and Yugoslav governments was not possible. U.S. Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius recommended that further discussion was needed on this issue between the British and American Ambassadors and Molotov in Moscow. They were all in agreement with this proposal.

Both the Anglo-American and Soviet blocks established spheres of control or influence in Europe. Anglo-American troops occupied countries in Western Europe while Soviet troops occupied countries in Eastern Europe. An East-West split emerged dividing Europe into two antagonistic and antithetical camps or blocks. This was the beginning of the post-war Cold War.

Who won and lost at Yalta? The U.S. Secretary of State Edward Stettinius was “of the opinion that it was Stalin who made the greatest concessions, which the Soviet Government then began to whittle away almost at once.” The three Allied Powers all sought to maximize their national security interests at Yalta.

The Tito-Subasic Agreement

Ivan Subasic, the Prime Minister of the Yugoslav Royalist Government in Exile in London headed by Peter II, had signed the agreement or sporazum with Tito to form a provisional government. This agreement was endorsed at Yalta.

Subasic was an ethnic Croat who had been the pre-war Ban or Governor of Croatia who was regarded as a moderate but who had scant sympathy or concern for the Serbian position. He openly came out against Draza Mihailovich and voiced his opposition to his military leadership in the media. His appointment was a clear sign of a precipitous shift to Tito and the Partisans and a rejection and abandonment of Mihailovich and the monarchy.

He met with Tito whom he described as “reasonable” and who he maintained was not a Communist ideologue. His impressions of Tito were very positive. He also met with Joseph Stalin in Moscow. Stalin told him that a monarchy was acceptable in Yugoslavia so long as the people supported it. Stalin cautioned about Yugoslavia trying to copy the Soviet or Stalinist model. Yugoslavia was a different scenario, Stalin averred. Yugoslavia should be a democracy. Stalin asked Subasic if Peter II had the support of the people of Yugoslavia. Subasic told him that he was not popular in Croatia, Slovenia, and Macedonia. He was very favorably impressed with Stalin.

Peter went to the Mediterranean to oversee the negotiations. He flew to Malta on June 11, 1944 on Winston Churchill’s Dakota aircraft. On June 18, he flew by plane to Caserta in southern Italy. The next day he visited Pompeii and had dinner with British General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson. On June 20, he flew over Cassino, Anzio, and Rome on Wilson’s Dakota. By lunchtime on June 20, Ivan Subasic had arrived in Caserta. They discussed the Subasic-Tito agreement reached on June 16. On June 21, Peter flew to Rome. Peter met with British General Harold Alexander and Pope Pius XII at the Vatican. They talked about the Communist threat with the Pope. The next day, June 22, Peter went to see the Allied Front in Rome. He returned to Caserta where Wilson wanted him to meet personally with Tito. Tito refused on the grounds that he could not leave Yugoslav territory according to Peter. But this is not shown by the facts. Tito went to Moscow to see Stalin. And he went to Italy to meet with Churchill and Subasic. The next day, June 23, Peter returned to London.

Subasic was photographed conferring with Peter after the sporazum or agreement with Tito in late June, 1944. Peter’s facial expression evinced his doubts and disapproval of the plan.

Subasic was also photographed with Winston Churchill and Tito in Italy on August 15, 1944, after a conference endorsing their sporazum.

The 1943 Big Three Conference in Tehran, Iran had already decided the major issues regarding Yugoslavia. The Allies agreed to put their support in Tito and the Partisan Movement and to withdraw their support from Draza Mihailovich. The Communist dictatorship that was ratified at Yalta was, in essence, a fait accompli after Tehran. Yalta was only concerned with forming an interim government and attempting to assure that the final government would be democratically decided and elected.

Tito and Subasic signed the coalition government agreement or sporazum in Vis on June 16, 1944. The second agreement was signed on November 1, 1944.

The Big Three at Yalta endorsed this agreement. Franklin D. Roosevelt released a Joint Statement with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin on the Yalta Conference, on February 11, 1945.

Media accounts in the U.S. reported positively about the ratification of the new coalition government. The Kingston Daily Freeman in New York for February 13, 1945 reported: “Yugoslavia — Marshal Tito, now in control within the country, and Dr. Subasic, chief of the exile government at London, are being told to get their projected coalition administration set up at Belgrade without delay.”

Media Accounts

Media reports in the U.S., UK, and Soviet Union were positive and uncritical of events and developments at the conference. The New York Times front page headline of Tuesday, February 13, 1945 read: “Big 3 Doom Nazism and Reich Militarism; Agree On Freed Lands and Oaks Voting; Convoke United Nations in U.S. April 25.”

The Stars and Stripes, the daily newspaper of the U.S. Armed Forces, in the Thursday, February 8, 1945 issue, focused on how the conference planned the end of the war: “‘Big 3’ Map Victory Drive At Black Sea Conference.” “They Meet Again to Talk of War and Peace.”

In the UK, The Daily Express for Tuesday, February 13, 1945 reported that the Allied Powers had negotiated and agreed on the resolution of the war: “Big 3: Germany to Pay.” “Victory and Peace Plan Drawn Up in Crimea.” “The Three — First picture from the Palace in Crimea.” “The Big Three Meeting Again To Make Plans For the World.”

The Daily Express also emphasized that the Allied meeting would determine the close to the conflict and what would follow: “Crimea Conference- Big 3. Big 3 Decide ‘Now We End It’”. “Reich to be occupied in three zones.” “Germany to pay in full.” “Crimea Conference tells Germany it is hopeless to resist — and gives these plans: 1. Last all-out attack. 2. Joint control in Berlin. 3. Nazi arsenals to be scrapped. 4. Curzon Line for Poland. 5. Peace Council.”

The Daily Mail for Tuesday, February 13 1945 likewise highlighted Allied unanimity and agreement: “Crimea Conference – Big 3. Big Three’s Final Plans For Germany. ‘Unconditional Surrender’.”

The Bethlehem Globe-Times in Pennsylvania for February 12, 1945 focused on the issue of Allied unity and consensus: “Big 3 Agree On Joint Command To Smash Nazis. Deals Blow To Hitler-Himmler Hopes That United Nations Unity Might Fall Apart.”

The USSR was portrayed as an ally and partner of the U.S. FDR was photographed reviewing a Russian Honor Guard in a Jeep at Yalta in Crimea after arriving at the airport for the Yalta Conference. Winston Churchill and Vyacheslav Molotov could be seen on the left, walking beside the Jeep. The reason for the Jeep transport was not discussed at that time. It was due to FDR’s inability to walk on his own.

The momentum of the war was on the side of the Soviet Union at the time of the Conference. By the time of the Yalta Conference, Marshal Georgi Zhukov’s Red Army troops were 40 miles or 65 kilometers from Berlin. Soviet troops would take Berlin and end the war in Europe. Meanwhile, American troops were bogged down in the war with Japan. The invasion of mainland Japan was planned. FDR was seeking Soviet help against Japan.

FDR’s Report to Congress

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt sat in front of network radio microphones as he reported to a joint session of Congress on the results of his participation in the Yalta Summit Conference in Crimea on March 1, 1945.

The radio speech was broadcast across the United States. 20th Century Fox filmed a newsreel of the speech entitled “Roosevelt Reports To Congress On Yalta Parley.”

FDR emphasized that “America will have to take the responsibility for world collaboration”, that global engagement was necessary.

FDR stated that the outcome of Yalta would be the establishment of a framework for future peace and stability:

“I come from the Crimea Conference with a firm belief that we have made a good start on the road to a world of peace. Never before have the major Allies been more closely united, not only in their war aims, but also in their peace aims. And they’re determined to continue to be united, to be united with each other, and with all peace-loving nations, so that the ideal of lasting peace will become a reality. … I’ve seen Sevastopol and Yalta, and I know there is not room enough on earth for both German militarism and Christian decency. And I am confident that the Congress and the American people will accept the results of this Conference as the beginnings of a permanent structure of peace, upon which we can begin to build, under God, that better world, in which our children and grandchildren, yours and mine, the children and grandchildren of the whole world, must live, and can live.”

FDR’s health was rapidly declining at this time. At the time of the Yalta Conference, Franklin D. Roosevelt was 63, Winston Churchill was 71, and Joseph Stalin was 67. Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, two months after the Yalta Conference.

The Fate of the Yugoslav Monarchy

What was to become of the Yugoslav monarchy? U.S. Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius recalled that there was no British support for retaining the Yugoslav monarchy: “In a message from Ambassador [to the UK, John] Wynant, several weeks prior to Yalta, we had been informed that Mr. Churchill had told King Peter: ‘The three Great powers will not lift one finger nor sacrifice one man to put any king back on any throne in Europe.’ This was an amazing statement in view of Churchill’s favorable attitude toward the Italian and Greek monarchies.” Churchill based his support on whether it served British interests at that time.

On November 1, 1944, the second agreement between Tito and Subasic was signed. The two amendments, however, had little effect on the outcome in Yugoslavia. Tito was to select 21 ministers while Subasic was to pick six. Peter disavowed the agreement because it gave power to Tito and disenfranchised him.

Tito was to be Prime Minister and Subasic Foreign Minister in the new Yugoslav coalition government. There were to be free and unfettered elections and a representative government of all the peoples of Yugoslavia. Tito accepted the regency but did not allow Peter to choose the members.

At the February 8, 1945 plenary session at Yalta, Stalin asked Churchill to explain and summarize the situation in Yugoslavia and Greece.

On February 9, the Yugoslav issue was resolved. Subasic was to fly to Yugoslavia the next day. Stalin supported this because his presence would bring balance to the government in Yugoslavia. Churchill, however, dismissed this, stating that his presence would have no effect on the government because “as Tito was a dictator and could do what he wants.” Stalin denied this assertion. Churchill clearly understood the power relations in Yugoslavia and Subasic’s insignificant figurehead role in the new regime and what it entailed for the monarchy. And yet, Churchill was the architect and instigator of the plan. He was maintaining two contradictory views simultaneously.

Stalin was not in principle against the re-establishment of the monarchy in Yugoslavia or of monarchies in the Balkans. He said, ‘”If a King can be more useful in waging war against the enemy and maintaining stability after victory, he would prefer him to a makeshift Republic.”

Stalin expressed support for Peter: “He seems to be a young man who is close to his people.” He emphasized that a plebiscite needed to be conducted to determine the popular support for his return. Churchill respond: “When time comes I shall see to it that the plebiscite is conducted under British, Russian and American supervision.”

On January 29, 1945, a week before Yalta, Churchill understood full well that the agreement was a ploy and a scheme to install Tito in power. Churchill noted: “I do not like this agreement. It appears to set up a dictatorship by Tito, who has the army under his control. But I do not see any other way to solve the problem and I shall advise the King to sign the agreement.”

Churchill understood and noted as well that the agreement does not allow for other political parties. It establishes a single party, the Communist party set up by the Partisan movement. He further noted that the members of the AVNOJ, or the Partisan Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation, were not elected representatives of the people.

Subasic recommended that the way to prevent a Partisan or Communist takeover was by the futile and disingenuous proposal that the council be expanded by including non-Partisan members in the Parliament. This was clearly an ineffectual and superficial suggestion with no practical result. At best, these would be merely token members meant for show only.

Peter understood the import of the agreement immediately and rejected it outright. He told the British Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs Alexander Cadogan: “Please tell Mr. Churchill that … I was shocked by this agreement and I shall not accept it.”

Cadogan reported: “King Peter told Churchill that he regarded the agreement as a polite way to oust the King quietly, that … he wished to disavow Subasich immediately for transgressing his powers and for proceeding to Moscow without first reporting to him.”

Churchill reportedly revealed his suspicions: “You know I do not trust Tito. He surreptitiously flew to Moscow to meet with Stalin before my arrival in London. He is nothing but a Communist thug, but he is in power and we must reckon with that fact. President Roosevelt, Stalin, and I have agreed that there will be a plebiscite by which the people of Yugoslavia will decide on the question of the Monarchy. Your return, therefore, will have to be postponed until the plebiscite takes place.”

Peter dismissed this suggestion as naïve and utterly unrealistic: “What chance have I in a plebiscite when Tito is in Yugoslavia? It will be nothing but a farce.” Churchill then stated that he would insure that the plebiscite would be supervised by “impartial umpires” including “British, Americans and Russians.”

During the conversation, Peter told Churchill: “I have followed your advice, Mr. Prime Minister, since I escaped from Yugoslavia, and look where I am today.” Churchill’s response was to shift blame to Draza Mihailovich: “Would you have been better off if you had followed Mihailovich?”

Peter’s fears and apprehensions would be realized. A Communist dictatorship government would emerge in Yugoslavia. That government would abolish the monarchy on November 29, 1945.

Endgame

The Yalta Conference gave legitimacy and endorsed the sham Tito-Subasic Agreement. As all concerned understood, the agreement ratified the Tito Communist dictatorship regime. The U.S., British, and Soviet governments all played a role in ensuring this outcome. This was the impact of Yalta on Yugoslavia.

Bibliography

King Peter II of Yugoslavia. A King’s Heritage. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1954.

Laloy, Jean. Yalta: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. New York: Harper and Row, 1988,

Plokhy, S.M. Yalta: The Price of Peace. New York: Viking, 2010.

Snell, John C. , ed. Forrest C. Pogue, Charles F. Delzell, and George A. Lensen. Introduction by Paul H. Clyde. The Meaning of Yalta: Big Three Diplomacy and the New Balance of Power. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1956.

Stettinius, Edward R. Roosevelt and the Russians: The Yalta Conference. Ed. by Walter Johnson. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1949.

Sulzberger, G.L. Such a Peace: The Roots and Ashes of Yalta. New York: Continuum, 1982.

Originally published on 2017-10-07

Author: Carl Savich

Source: Serbianna

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.