Views: 1348

The Consequences of WWI and the Yugoslavs

The end of WWI in November 1918 as a consequence of the military collapse of the Central Powers and the following series of peace treaties of Versailles on June 28th, 1919 between the Allies and Germany, of St Germain on September 10th, 1919 with Austria, of Neuilly on November 27th, 1919 with Bulgaria, and finally of Trianon on June 4th, 1920 with Hungary, produced major border changes in Central, South-East, and East Europe as the continent saw the emergence of several of new states and the enlargement of others fortunate enough to be on the side of the victorious powers. After 1919, new states included the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), Finland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia (under such formal name from 1929).[1] Romania enlarged itself greatly, taking Transylvania from Hungary, Bukovina from Austria, and Bessarabia from Russia.[2]

As a matter of fact, the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire, the disarmament of Germany, and the effects of the 1917 Russian Revolution followed by the 1917−1921 Russian Civil War completely altered the balance of power in Europe. Potentially Germany, in terms of its population and industrial power, became after 1919 without any counterbalance in Europe. The only hope of all of those states who stood to lose by a revision of the post-WWI peace treaties was the maintenance of overwhelming military strength in an alliance against any revival of German power.

The most important consequence of the First World War (the Great War)[3] concerning the Balkan Peninsula were the dissolution of the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy (the Dual Monarchy) and the creation of a new Balkan state – the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the KSCS)[4] proclaimed in Zagreb on November 23rd, 1918 and confirmed as a new political reality in Belgrade on December 1st, of the same year.[5] The KSCS was comprising the territories of the before-WWI independent Kingdoms of Montenegro and Serbia and former Habsburg and Ottoman Balkan provinces. However, in the Balkan, Yugoslav and even international historiography there is still a false interpretation of the historical sources and political events based on them upon the question when and where the KSCS was proclaimed as it is interpreted to be in Belgrade on December 1st, 1918.[6] Nevertheless, whether within the boundaries its leaders proposed or those that were finally accepted by several international post-WWI international peace treaties, the lands that made up the new state of the KSCS became for sure the most complex in the Central, South-East, and East Europe. Those lands included five of the South Slavic peoples (approximately 10 million inhabitants) but as well as several minority peoples from every ethnolinguistic group in the Balkans (approximately 2 million inhabitants).[7] For the reason that the territory of the KSCS was ruled by four different states before WWI, there were four different currencies, railway networks, and banking systems. At the time of its formal declaration of independence, the country had two Governments: the National Council in Zagreb and the Royal Serbian Government in Belgrade. In fact, the territory of the KSCS was divided between the independent South Slavic countries of Serbia and Montenegro (both of them enlarged their territories during the 1912−1913 Balkan Wars), and the Austria-Hungary (former the Habsburg Empire), which in turn was subdivided on the South Slavic territory into several Austrian provinces (Carniola, Styria, Dalmatia), the Hungarian Kingdom (Croatia, Slavonia, Bačka, Banat), and jointly administered Austro-Hungarian province of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

As a matter of fact, the sources and facts are clearly telling that a common Yugoslav state was in fact proclaimed in Zagreb (Croatia) on November 23rd, 1918 but not in Belgrade (Serbia). In the capital of the Kingdom of Serbia on December 1st, 1918 it was only confirmed already proclaimed a common state of all Serbs, Croats and Slovenes by a Montenegrin regent Alexander Karađorđević on the throne of the Kingdom of Serbia.[8] As was mentioned, the new state was composed of the pre-war territorial parts of the territories of the Kingdom of Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro and the Dual Monarchy populated by the South Slavs. The last territory (of the Dual Monarchy) gave around 50% of the new state. Nevertheless, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes became after December 1918 the biggest country at the Balkans and one of the bigger states in Europe from the territorial point of view.[9] The country was in fact created, proclaimed and recognized as such just by the politicians in Zagreb and Belgrade but not by any kind of the people’s referenda or plebiscite either on the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia or the South Slavic lands of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

During WWI, the idea of Yugoslav unification was advocated by three different political actors: The Yugoslav Committee (formed in April 1915 by a group of Croat, Serb, and Slovenian political emigrants from the Dual Monarchy), The National Council (formed in Zagreb on October 29th, 1918, at which time it declared the independence of all South Slavic lands in the Dual Monarchy), and the Royal Serbian Government (which as an ally of the Entente regained full control of Serbia in November 1918). In regard with Montenegro, exile leaders had their own wartime committee in Paris and favored joining Serbia, although this political combination did not happen until Montenegro’s King Nicholas I (who opposed the unification with Serbia) became formally deposed on November 24th, 1918, by a pro-unification Assembly of Montenegro in Podgorica. By December 1st, 1918, all South Slavs except the Bulgarians have been brought together within the borders of the KSCS and under the leadership of the Karadjordjević dynasty of Serbia.

During the process of political-state’s unification of the Yugoslavs into their own single national and independent state during the First World War, several important documents were issued by the representative institutions of them with regard to the creation and internal political and administrative organization of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Without any doubt, the 1917 Corfu Declaration is the most significant and crucial document among all of them. It was signed on July 20th, 1917 between the Royal Government of the Kingdom of Serbia and the representatives of the Yugoslav Committee – a political organization established in 1915 in London with the intention to represent the South Slavs from the Dual Monarchy. The Corfu Declaration became a basis for further process of unification and, what is even more important, a basis for the conception of the internal political organization of the new state after 1918. However, the conclusions of this document were changed in the Geneva Declaration signed on November 9th, 1918 by the representatives of the Royal Government of the Kingdom of Serbia, the National Council in Zagreb, the Yugoslav Committee and the parliamentary groups. Nevertheless, the proclamation of the new state in Zagreb on November 23rd, 1918 was officially accepted and verified in Belgrade by Serbia’s side on December 1st, 1918 mainly on the basis of the Corfu Declaration but not on the Geneva one.

After the formal proclamation of a new state at the very end of WWI, the KSCS faced immediately the focal problem that was the new country’s borders. In regard to this issue, the KSCS’ delegation at the Paris Peace Conference assumed that besides formerly independent Kingdom of Serbia (largely expanded along its eastern, western and northern boundaries in November 1918) and Kingdom of Montenegro (united with Serbia in November 1918), the new state would include all ex-Austro-Hungarian provinces south of the Drava and Danube rivers followed by several lands north of that line (Klagenfurt region, Prekomurje, and Medjumurje). A territory of historical Banat was divided between the Kingdom of Romania (with Timişoara) and the KSCS (with Vršac).

During and after WWI the strongest challenge to the territorial claims of the Yugoslavs came from Italy – a country which was during the war a fellow of the Entente. Italy was itself very interested to annex large parts of East Adriatic (Istria, Dalmatia, and the islands) that was before 1918 part of the Dual Monarchy. Therefore, one of the reasons for the convocation of the 1917 Corfu Conference was to beat Italian territorial aspirations in the area of East Adriatic. The final settlement of the border issue between Italy and the KSCS was fixed by the Treaty of Rapallo signed on November 12th, 1920, by which Italy acquired the coastal territories of ex-Dual Monarchy (Gorizia-Gradisca, Trieste, Istria), a few East Adriatic islands (Cres, Lošinj, Lastovo), and the town of Zadar. However, no one side was fully satisfied with the treaty.[10]

Undoubtedly, Italian territorial aspirations, as well as its diplomatic and military threat at the Balkan Peninsula, was for both Serbia’s Royal Government and the Yugoslav Committee one of the most important reasons to convoke the Corfu Conference in July 1917. Both of them wanted to make publicly known that one single and vigorous South Slavic state would be created on the central and western parts of the Balkans which could defend itself from the Italian pressure. Consequently, the Yugoslav Committee would preserve the South Slavic Adriatic littoral, while Serbia’s Royal Government would be in the position to preserve the South Slavic territories of West Macedonia and Kosovo-Metohia. It is interesting to notice that the Corfu island, as a conference meeting place, was located just between Albania and Epirus – two territories under the strongest Italian political-military pressure at that time.

That Italy was making a serious threat for Serbia in relation to Albania and Epirus in the first half of 1917 was finally approved on June 3rd, 1917 when the Italian general Ferraro, under instructions given by his Government, proclaimed the Italian protectorate over Albania. According to Serbia’s Prime Minister Nikola Pašić’s circular note which was sent to France, the United Kingdom, Russia, and the USA, this proclamation was against the axioms adopted by the Entente states that this war was fought against the German imperialism and militarism for the principle of the self-determination of the nations. N. Pašić noticed that this Italian proclamation was against the “vital interests of the Serbian people” for their future, but also and against the “vital interests of the Serbian state”.[11] In fact, he was afraid that Italy could close Serbia’s exit to the sea via the Morava-Vardar valley. At the end of June 1917, during the Corfu Conference, N. Pašić confirmed that Italy was working against Albanian leader Esad-Pasha, Serbia and Greece by making two Albanian Governments – the northern and the southern ones.[12] For the Royal Government of Serbia, it was totally clear that Italian diplomacy was working against the interests of the South Slavs in July 1917, which was again confirmed in December 1917. Taking into account the information given by Serbia’s ambassador in London, Jovan M. Jovanović, to the Regent Alexander I Karadjordjević of Serbia, only Italy was against the South Slavic unification among all Entente members.

It has to be noticed that the Italians had three crucial principles of their Balkan policy: 1) Sacro egoismo Italiano; 2) Not to allow a total dismemberment of Austria-Hungary under the principle of the self-determination of the nations; and 3) Not to allow the creation of a single South Slavic state.[13] According to the information given by J. M. Jovanović from December 1917, the Italian politicians around the Italian Premier Vittorio Emmanuelle Orlando (1860–1952) in the Italian Government wanted to occupy Dalmatia for Italy,[14] to create a small Serbia and to thwart the South Slavic unification. This Orlando’s political orientation was pro-Germanic and naturally anti-Serbian.[15]

Why Serbia de facto recognized the Yugoslav Committee in summer 1917?

The preparations for the 1917 Corfu Conference can be traced from the moment when the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Serbia Nikola Pašić (1845−1926) sent an invitation to the President of the Yugoslav Committee in London, a Croat from Dalmatian city of Split – Dr. Ante Trumbić, at the beginning of May 1917. Dr. Trumbić was invited, in fact, to come to the Corfu island in Greece with other four members of the Yugoslav Committee in order to make an agreement with the Royal Government of Serbia with regard to the most urgent and important questions about the creation of the new Serbo-Croat-Slovenian state.[16] Therefore, the most significant question which needs appropriate answer in this matter is: Why did Nikola Pašić decide to negotiate with the Yugoslav Committee at that time and at such a way to recognize it de facto (but not and de iure) as an equal political actor to the Royal Serbian Government upon the process of the Yugoslav unification – an actor which was to represent all South Slavs from the Dual Monarchy?

In order to give an answer to this question, we have to take into consideration N. Pašić’s opinion about the functions of the Yugoslav Committee from the time of its very foundation. The Yugoslav Committee was established on April 30th, 1915 in Paris by the South Slavs who were exiled from the territory of the Dual Monarchy during the first months of the war. The reason for its establishment was of the very practical political nature: it was the answer to the secret Treaty of London, signed between Italy and the Entente states of the United Kingdom, France, and Russia. The treaty was signed on April 26th, 1915 at the expense of Austria-Hungary but primarily at the expense of the South Slavic territories in the Dual Monarchy claimed by the Croats and Slovenes (Istria, Dalmatia, and the Adriatic islands). Therefore, the creation of the Yugoslav Committee was, in fact, an act of protection of national interests and rights of the South Slavs from the Dual Monarchy,[17] i.e., of the Austro-Hungarian Croats and Slovenes but not of the Austro-Hungarian Serbs or neighboring Serbia. The member-politicians of the Yugoslav Committee (established in Paris but soon moved to London because of diplomatic reasons) claimed to represent all South Slavs from the Dual Monarchy to the Entente powers in order to protect their national interest and ethnohistorical rights for the time after the end of the First World War at the peace conference.[18] It means that the Yugoslav Committee was pretending to represent the peoples from the following South-Slavic ethnohistorical regions: Istria, Dalmatia, Međumurje, Prekomurje, Kranjska, South Štajerska (Styria), South-West Koruška (Carniola), Croatia, Slavonia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Kotor Bay, Baranja, Srem, Banat and Bačka. At that time, as the South Slavs, in these regions have been recognized as the separate ethnolinguistic nationalities: the Slovenes (Kranjci), Croats and Serbs.[19]

In regard to the question of N. Pašić’s attitude towards the existence of the Yugoslav Committee and its function during the war, the most important problem was the fact that the Yugoslav Committee understood itself as the only competent political representative organization of all South Slavs from the Dual Monarchy, what means including and the Austrian-Hungarian Serbs. On other hand, Serbia’s Prime Minister did not want to accept the Yugoslav Committee as the legal political-national representative organisation of the South Slavs from the Dual Monarchy but only as the patriotic organisation with the only aim to fight for the Yugoslav (the South Slavic from the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary) national interests, and to inform the public opinion in the United Kingdom (where it was located) and Europe about the Yugoslav question in Austria-Hungary.[20] According to Vojislav Vučković, N. Pašić was in the opinion that the political role of the Yugoslav Committee was just “to inform the Allies about the sufferings of the South Slav lands under the Austrian-Hungarian rule and to present their national intentions”.[21] These were the crucial reasons for N. Pašić that he never before the Corfu Conference recognized in practice the Yugoslav Committee as de facto the equal political-representative institution to Royal Serbia’s Government upon the process of the Serbo-Croat-Slovenian state’s unification. However, in May 1917 he decided to negotiate with the Yugoslav Committee as a representative institution of the South Slavs from the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary and at such a way to recognize it as one of the legal subjects in the process of the unification. Moreover, thus, he de facto recognized the Yugoslav Committee even as the equal negotiating-representative subject with Serbia’s Royal Government. Nevertheless, up to that time he claimed only for Serbia exclusive rights to represent all South Slavs before the Entente contracting powers and only for the Kingdom of Serbia to work on their unification into a single national state. Therefore, the most significant question in regard to the mentioned above is: What was the main reason for N. Pašić to drastically change in May 1917 his opinion towards the role and function of the Yugoslav Committee?

The answers to the above questions are coming from the very fact that Imperial Russia was the only supporter of Serbia’s plan to create the united national state of all ethnolinguistic Serbs in South-East Europe after the war on the ruins of Austria-Hungary. On the other hand, Serbia’s Royal Government was aware that both the country and the national interest of the Serbs can be protected only by Imperial Russia. N. Pašić was convinced even in 1912, just before the Balkan Wars started, that only Russia can save Serbia from the aggression by the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.[22] It is known that the Balkan policy of Russia in the 19th century was led by the main idea that the Russian influence in this region should be realized by supporting Bulgaria and Serbia.[23] It was the main reason for Imperial Russia to create either a Greater Bulgaria (like according to the San Stefano Peace Treaty with the Ottoman Empire signed on March 3rd, 1878)[24] or a Greater Serbia (during the First World War in 1915−1917). Because of the very fact that in the First World War Bulgaria from October 1915 was fighting on the opposite side (together with Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire), the crucial pivot in the Russian Balkan policy became from October 1915 the Kingdom of Serbia.[25] Probably as the best example of the Russian attitude about the Balkan affairs can be seen in proposal given by the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergei D. Sazonov (1860−1927), in September 1914 to Serbia’s ambassador to Russia: regardless to the fact that Sazonov understood well that the purpose of Serbo-Croat-Slovenian common state in the future is to be a counterbalance against Italy, Hungary, and Romania but, however, he did not advise Serbia to create a common state with the Roman Catholic Croats and Slovenes as they will be in such state all the time just an instrument used by the Vatican in its policy of destroying the Orthodoxy in East Europe.[26] The Russian authority, therefore, preferred the creation of a strong Orthodox united national state of the Serbs in the form of a Greater Serbia at the Balkans.[27]

As a very historical fact, both the military and political situation which faced the Kingdom of Serbia in late spring 1917 basically forced N. Pašić to back down in his position up to that time that Serbia had to have the exclusive right to play a role of the Yugoslav Piemond concerning the political unification of the South Slavs except for the Bulgarians but also to decide upon its internal organization. For Serbia, after the 1917 February Revolution in Russia, it was quite necessary to overcome many unfavorable conditions in global politics, to perceive negative changes that brought the end of an old imperial political system in Russia, and the appearance of the Bolsheviks on the historical stage. In addition, Serbia had to win the sympathies of the new WWI ally – the USA, to dispel Entente’s doubts about Serbia’s intentions and the practical possibility of the unification of the Yugoslavs, to face the very fact that the Central Powers had not been militarily defeated, and finally that little thought was given to the disintegration of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.[28] Shortly, for N. Pašić it became quite clear that after February 1917, the Serbian war aims and political program formulated in December 1914 needed to be realized without the backing by mighty imperial Russia being at the same time aware of the powerlessness of the new Russian authorities expressing his reservation about their assertion that they wanted liberation of oppressed nations of the Dual Monarchy, creation of united Yugoslav state, and protection of small Serbia from the German threat in the future. According to Serbian historian Đ. Stanković, the fact that Serbia’s PM N. Pašić organized the Corfu Conference in June−July 1917 without the knowledge of the Russian authorities was the best proof of it.[29]

N. Pašić did not want to abandon Serbia’s vision of statehood, as it was officially declared in Serbia’s war program on December 7th, 1914 and, therefore, N. Pašić in the spring of 1917 persisted in the position that Serbia was a focal proponent of common ideas by the Yugoslavs and their official and responsible diplomatic representative before the Entente and the rest of the world. For that reason, N. Pašic was prepared only to commend the Yugoslav Committee for its patriotic efforts concerning the unification. At the same time, Dr. Ante Trumbić as a president of the Yugoslav Committee recognized that no one of Yugoslav countries was capable of being a Piemond as Serbia was. However, at the same time, there were several main differences in regard to the process of unification between the Yugoslav Committee and Serbia’s Royal Government as on the volunteer question, methods of unification, and the character of the internal organization of the future common state. Nevertheless, the political circumstances forced both N. Pašić and A. Trumbić to narrow down their differences despite all their disagreements and to participate at the Corfu Conference recognizing each other as official political actors in the process of unification.[30]

The basic and ultimate aim by N. Pašić and his wartime Royal Government of Serbia during the entire Great War was firstly to resolve the Serbian question if possible by the creation of a single and united common state of all Serbs in the Balkans. A prospect for the creation of such a state after the war in the case of the Entente military victory was given by the Entente powers to Serbia’s Royal Government during the secret negotiations in London in April 1915 when finally a secret London Treaty was signed on April 26th of the same year. However, in order to realize this offer by the Entente, Serbia had to cede Bulgaria her portion of historical-geographical Macedonia that was gained after the Second Balkan War in 1913 according to the Bucharest Peace Treaty in August 1913 (the so-called Vardar Macedonia). Nevertheless, the main guarantee to Serbia upon the realization of this offer was the Russian Empire. However, the Government of Serbia rejected to cede the Vardar Macedonia to Bulgaria in 1915 hoping to create a Greater Serbia after the war by inclusion into the united national state of all Serbs and Vardar Macedonia (called as well as Vardar Serbia or South Serbia).

The “Yugoslav” option for the Royal Government of Serbia was, in fact, only the second one, or better to say – an unhappy alternative, just in the case that the first option of a united national state of all Serbs cannot be realized in the practice after the war for any reason. It means that any kind of Yugoslavia (centralized, federal, etc.), as a common state of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, for Serbia was as well as an option of her war aims for the very reason to solve the Serbian national question just in this case the Serbs have to live together with the Roman Catholic Croats and Slovenes in a single state what finally appeared to be tragic for the Serbs especially during the Second World War.[31] N. Pašić himself was a strong supporter of the creation of only a united Serbian national state (the first and prime option) instead of the common South Slavic state together with Croats and Slovenes (the second and only alternative option but not the prime one) until the spring 1917 when he decided to negotiate with the Yugoslav Committee on the equal political level for the sake of the creation of Yugoslavia instead of a united national state just of the Serbs in a form of a Greater Serbia. Therefore, in this context, the crucial question is: What was the real reason for N. Pašić to finally opt for the creation of Yugoslavia but not for a Greater Serbia in spring 1917?

On the other hand, the “Yugoslav” option was and for the Yugoslav Committee only the alternative one, but not the main political aim to be realized after the Great War. We have to keep in mind that the top leadership of the Yugoslav Committee was composed by the ethnic Croats (like the Communist Party of Yugoslavia during the Second World War) and it was led primarily by two Croat politicians from Dalmatian seaport of Split: the President Dr. Ante Trumbić (1864−1938) and Dr. Josip Smodlaka (1869−1956) who, both of them, have been Croatian ultra-nationalists. After them, the most influential committee members have been also the Croats: Ivan Meštrović, Hinko Hinković, the brothers Gazzari and others. Even the original name of the Yugoslav Committee was, in fact, the Croatian Committee, established in Rome but the name was changed very soon just for political reasons. Nevertheless, it was obvious, and for N. Pašić and for the rest of his Government, that the Yugoslav Committee was fighting exclusively for the Croat national interest and that the „Yugoslav“ name was chosen just to hide the Croat nationalism under the quasi-Yugoslavism.[32] What is the most important to say about the Yugoslav Committee is that this, in fact, a Croat national(istic) organization was deeply imbued by the political ideology of the ultra-nationalistic Croatian Party of Rights, established by a Croat racist Ante Starčević in 1861. According to the party ideology, all South Slavs have been ethnolinguistic Croats while the Serbs had to be physically exterminated by the „axes“. Therefore, the Slovenians were nothing else than „Alpine“ or „White“ Croats, Montenegro was a „Red Croatia“ and all Serbs were understood just as the Orthodox Croats. The President of the Yugoslav Committee Dr. A. Trumbić was a member of this party till 1905 and Dr. Frano Supilo was in his youth a fellow of the same party. The main political aim of the Croatian Party of Rights was to establish ethnically pure Greater Croatia including all provinces of the Dual Monarchy populated by the South Slavs what was at the same time, in fact, and the crucial political aim of the Yugoslav Committee to be achieved after the war.[33] However, the “Yugoslav” option was for the leadership of the Yugoslav Committee, likewise and for N. Pašić in the case of Serbia, just the alternative one if the crucial political aim (a Greater Croatia) was going not to be realized for some reason.

The main reasons for the convocation of the Corfu Conference in 1917

With regard to the question of the convocation of the Corfu Conference in June−July 1917, according to Dr. A. Trumbić, the main reasons and tasks of the conference were:

- The 1917 February/March Revolution in Russia followed by the US entering the war in April of the same year created new war circumstances and international atmosphere favorable for direct and ultimate negotiations between the Royal Government of Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee in London upon the future of the South Slavs after the Great War.

- Therefore, from spring 1917, it was impossible any more to keep the principles of the unification advocated by the Royal Government of Serbia.

- It was necessary to formulate officially one and common program of the unification of the South Slavs.

- It was necessary to agree with the Royal Government of Serbia on “territorial unification and internal organization of the common state…”.[34]

Obviously, the consequences of the Russian February (March) Revolution concerning Russia’s foreign policy in the Balkans became the focal reason for N. Pašić to accept A. Trumbić’s Yugoslav Committee in London as a negotiating actor with regard to the destiny of the Yugoslavs after WWI. By March (new calendar) 1917 the strain of the Great War crucially weakened the Imperial Government in Russia with liberals, socialists, generals, nobles and businessmen who were plotting its overthrow. The disturbances in St. Petersburg destroyed in four days the Imperial administration with sheer hunger turning wage demands into a general strike and bread lines followed by anti-governmental demonstrations. The Emperor (Tsar) Nicholas II set out for the capital from his headquarters at Mogilev, but, however, became prevented by the railway workers from arriving and on March 15th he abdicated in Pskov. The governmental authority now passed to the Provisional Government that was established by several politicians from the Parliament (Duma). However, its real power became limited by the existence of the St. Petersburg’s Council (Soviet) of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies which looked to for leadership by Soviets throughout Russia, effectively constituted an alternative Government forming at such a way a “dual power” effect which brought political instability in the country.[35]

It is a true fact that after the 1917 February (March) Revolution in Russia all hopes by N. Pašić and his Royal Government concerning a possibility to create only a united national state of all Serbs but not Yugoslavia after the war disappeared for the very practical reason that a new Russian Government in St. Petersburg (Petrograd) did not give support for the creation of united national state of all Serbs.[36] In such a way, after March 1917 and the dethronement of the Russian Emperor Nicholas II, an idea of a Greater Serbia was not supported by any of Great Powers during the war.[37] In other words, historically and naturally, only Imperial Orthodox Russia was interested in the creation and existence of united Serbian lands – a state to be under the Russian protectorate.[38] N. Pašić’s main wartime task of the Kingdom of Serbia, based on a support by the Imperial Russia, disappeared when the new Russian Provisional Government declared on March 24th, 1917 that Russia wants to create around Serbia one “strongly organized Yugoslavia – as a barrier against the German aspirations”,[39] but not a Greater Serbia with the same function as Yugoslavia. In one word, Imperial Orthodox Russia, as the only supporter of the idea of a Greater Serbia, did not exist anymore, and for that real fact, the Prime Minister of Serbia had to adapt his post-war political plans to the new political reality in Europe after the 1917 Russian February (March) Revolution.[40] It means that the alternative “Yugoslav” option of solving the Serbian national question after the war became an optimal reality for the Government of Serbia in spring 1917, likewise for the Yugoslav Committee in London as well.

In the case of N. Pašić, it is obvious that the 1917 February (March) Russian Revolution was the crucial reason to change an attitude about Serbia’s war aims as he finally gave up idea to create a Greater Serbia and therefore accepted the idea of the creation of a common South Slavic state (without Bulgarians). However, in order to fulfill this new goal he had to directly negotiate with the representatives of the Yugoslav Committee, i.e., with the Croats. Nevertheless, it was only one out of three real reasons to bring together in the Corfu island in June−July 1917 around the table of negotiations the Royal Government of Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee.

The second reason, or better to say danger, became the possibility that the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary after the war would be preserved in some rearranged inner-administrative political form. The crux of the matter was that for both Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee, the existence of Austria-Hungary after the war in any form was an unacceptable political solution. The problem was that this idea from the side of the South Slavs in the Dual Monarchy emerged again on May 30th, 1917 when the “Yugoslav” deputies in the Austro-Hungarian Parliament (the “Yugoslav Club”) demanded reconstruction of the post-war Dual Monarchy on the bases that all Austro-Hungarian provinces populated by the South Slavs (the “Yugoslavs”) should form a separate federal part of the Dual Monarchy “under the scepter of the Habsburg dynasty”.[41] From this point of view, the Corfu Conference and its Declaration were the answers to the May Declaration by the South Slavic deputies in the Austria-Hungary’s Parliament. The third reason for convocation of the Corfu Conference was diplomatic mission to the Entente powers and its allies by Sixte de Bourbon, a brother-in-law of the last Austro-the Hungarian ruler (the Emperor Charles I of Austria and the King Charles IV of Hungary, 1916−1918), with regard to the possibility of signing a separate peace treaty with the Entente by the Dual Monarchy and at such a way to preserve the territorial integrity of the Dual Monarchy after the war. Therefore, the Corfu Declaration was a political demonstration by the Royal Government of Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee in London against any diplomatic attempt to preserve the Dual Monarchy after the war with the South Slavic provinces. However, in order to succeed in their anti-Austro-Hungarian plans, Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee had to achieve a bilateral agreement for the sake to have a common political platform before the Entente powers.[42] Both N. Pašić and A. Trumbić understood well the real menace of the political act when on May 30th, 1917 the Yugoslav Parliamentary Group voted in the Vienna Parliament in favor of the Imperial May Declaration. This Yugoslav parliamentary group was composed of 33 Slovenian, Croatian, and Serbian representatives in the Imperial Chamber in Vienna. In addressing the Parliament, those representatives stressed that founded on national principles and the Croatian State law the unification of all lands of the Monarchy inhabited by Slovenians, Croats, and Serbs was necessary. Those lands would form one autonomous political-territorial entity under the rule of the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty. In fact, the May Declaration represented the end of the dualist system of the organization of Austria-Hungary fixed in 1867 and the realization of a concept of the Yugoslav program.[43]

The Italian diplomatic and military campaign in Albania and Epirus in spring 1917 was the last reason for the convocation of the Corfu Conference, which resulted in the signing of the Corfu Declaration. At that time, both Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee were under the menace by the Italian territorial aspirations in West Balkans. As it was noticed earlier, the Yugoslav Committee was established in 1915 in order to protect one part of the Yugoslav (Croatian and Slovenian) lands from the Italian territorial demands. However, at that time, the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia was not in danger either from the Italian territorial aspirations or the Italian diplomatic and military influence in Central Balkans. That was one of the reasons why Serbia was not in a hurry to make a final agreement concerning the creation of Yugoslavia with the Yugoslav Committee. Nevertheless, in spring 1917, alongside with the Yugoslav Committee, the Royal Government of Serbia was as well as under strong Italian threat as the Italian diplomatic and military activities in Albania and Epirus (the territories in the neighborhood of the Kingdom of Serbia) became obvious. It means that the state’s territory and the borders of Serbia were in a question for the time after the war.

The first statement about the Italian political activities in Albania and Epirus, as a threat for Serbia, was sent to Serbia’s Regent A. Karađorđević, by Serbian vice-consul in Salonika, Nikola Jovanović, on March 3rd, 1917. According to him, the Italian plan was to unify Albania based on the Albanian claims on their ethnic rights. At that moment some Albanian ethnic lands (claimed by the Albanian propaganda to be only Albanian) have been under the Italian military occupation, and under the political protectorate of Rome. In fact, according to the report, a newly post-war Albania was to be, in fact, a Greater Albania, enlarged at least with Kosovo-Metohia and West Macedonia (and most probably with the Greek South Epirus), i.e., with the territories included into Serbia and Montenegro after the Balkan Wars in 1912–1913. The Serbian vice-consul thought that Italy wants to create a Greater Albania as the basis for the Italian political-economic post-war influence at the area of South Balkans (basically as the Italian colony as a territorial substitution for lost Ethiopia in 1896). The Serbian authorities have been in a strong opinion that Greater Albania under the Italian protectorate would be totally hostile towards Serbia and the Serbs what practically became true during WWII. In addition, the north-western Greek province of South Epirus was for the Italians only the “question of the Great Powers, but not the question of Greece”.[44] Only five days later, N. Pašić sent a telegram to the Regent Alexander I Karađorđević with the information that one Italian general gave an anti-Serbian speech in the Albanian town of Argirocastro criticizing Esad-Pasha’s pro-Serbian policy.[45] At that moment Esad-Pasha was only Albanian leader who co-operated with the Serbian Royal Government among all Albanian political leaders. The Serbian ambassador in Athens, Živojin Balugdžić, informed his Government on April 8th, 1917 that an agreement upon Albania between Italy and France was achieved in Paris. According to this agreement, Italy would get territorial concessions in South Albania and Epirus in return for the Italian support of Entente’s policy towards Greece.[46]

Before his coming to Corfu island for the negotiations with the Royal Government of Serbia, A. Trumbić met in Nice Stojan Protić, the former Minister in the Royal Government of Serbia and at that time a representative of this Government in the Yugoslav Committee. Their consultations ended by making the mutual draft about the basic subjects for the coming discussions in Corfu. However, they did not make any final conclusion about the subjects of the future negotiations as they have not been authorized to do it. That was a reason that they in Nice only agreed about the main questions to be discussed at Corfu where the Royal Government of Serbia with the army was exiled after the military collapse of Serbia in autumn 1915.

The Royal Government of Serbia on its session held on June 14th, 1917 decided to officially negotiate with the Yugoslav Committee. However, according to the Royal Government of Serbia, the fundamental questions about the final type of the internal political organization of the future Yugoslav state had to be agreed after the war but not during the Corfu Conference. Therefore, the Royal Government of Serbia decided to recognize the Yugoslav Committee as an important factor in a process of creation of Yugoslavia but not as a representative-political institution of the South-Slavic people from the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.[47] During the Corfu Conference, a President of the Yugoslav Committee A. Trumbić demanded that this organization should be recognized by Serbia as an official representative Government of all South-Slavs in the Dual Monarchy but this demand was rejected by N. Pašić.[48] Nevertheless, during the Corfu negotiations, an intention by the Royal Government of Serbia was to present the “Yugoslav Question” as an international problem.[49]

At the Corfu Conference held from June 15th to July 15th, 1918, the first official talks were held between the representatives of the Royal Government of Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee in London over several issues in regard to the question of Yugoslav unification but above all about the internal organization of future post-war Yugoslavia. During the negotiations, existed the division of views which have been quite opposite as the main problem was to establish either unitary or federalist form of internal constitutional arrangements. More precisely, those opposite views on the national question have been about the essence of the national unity of the so-called “three-named nation” of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenians, the content of the national unitary state, the form of state’s Constitution, and finally about the foundations of the interim Government. Serbia’s PM N. Pašić was in the opinion that, given the historical circumstances, the future of Yugoslavia was in the strong centralist and unitary state’s organization with local self-governmental authorities according to the existing Constitution of the Kingdom of Serbia. At the same time, he was rejecting the federalist system of state for the reason that it was being weak and short-term, promising to the representatives of the Yugoslav Committee to retain Croatian national, historical, and cultural specificities (coat-of-arms, anthem, alphabet, name, etc.). In contrast to N. Pašić’s opinion, the Croatian politicians insisted on the simultaneous existence of the centralist legislation and administration but along with separate autonomies, legislatures, executive bodies, and assemblies in individual historical provinces.

Opposite conceptions about the process of the Yugoslav unification and the internal political organization of the new state

It is very important to notice that during the Corfu Conference the opposite conceptions about the solving of the Yugoslav Question did not exist. Namely, there is an opinion at the Yugoslav historiography that during the Corfu Conference one conception was advocated by N. Pašić in a form of a Greater Serbia, i.e., Yugoslavia without Slovenes and Croats while the opposite conception was advocated by the Yugoslav Committee as the unification of all Yugoslav lands into a single state. However, Serbia’s Prime Minister concluded already before the Corfu Conference that liberation and unification of all Yugoslav people and their lands into a single state should be realized at the end of the war on a form of Yugoslavia but not in a form of a Greater Serbia. He finally accepted the idea of Yugoslavia instead of a Greater Serbia under both the new international circumstances after the 1917 February (March) Russian Revolution and the pressure by Serbia’s parliamentary opposition. Therefore, the process of unification of the South Slavic people into a single state and political form of it have been the topics on the agenda of the Corfu Conference in June−July 1920.

One of the basic problems during the Corfu negotiations between the Yugoslav Committee and the Royal Government of Serbia was a question about the name of a new state of the South-Slavs. The final agreement upon this question was to be the state of the “Serbs, Croats and Slovenes”,[50] but not “Yugoslavia” for two reasons:

- Firstly, such name of the state was an expression of a commonly accepted thesis by both negotiating sides, but mainly for political reason, that the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes are the “three-names nation” (the same nation just with three different names).

- Secondly, N. Pašić was extremely reserved towards the terms “Yugoslavia”, “Yugoslavs”, and “Yugoslav” as it was originally the ethnic name for the South Slavs of the Dual Monarchy used by the Austro-Hungarian authorities, but also and a propaganda terminology misused by Vienna and Budapest as a synonym for a Greater Serbia to be established at the ruins of the Dual Monarchy.[51]

N. Pašić himself did not insist on the concept of national pluralism, as an opposite to the national unitary state favored by the Yugoslav Committee as he wanted to preserve Serbian national name included as such into the name of a new state. He did not want to replace the name of the Serbs by some “artificial” one like the South Slavs, Yugoslavia or the Yugoslavs. A fact was that only the Serbs had at that time in independent states (Serbia and Montenegro)[52] among all Yugoslavs and exactly the Serbs have been the most historic nation among all of those who wanted to create Yugoslavia after the war. Up to that time (and later as well as), Serbia as the country mostly suffered during the First World War among all states involved in the conflict taking into consideration material damage and the loss of population percent.[53] For these reasons, N. Pašić was in a strong opinion that Serbia and the Serbs deserved to preserve their own national name within the official name of the new state after the war taking into consideration and the fact that Serbia had the crucial political role in the process of the unification as the “Yugoslav Piedmont”.

The Royal Government of Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee had opposite attitudes and about much more important issue that was the question of the internal political form and organization of the new state as the Yugoslav Committee was in favor of the republic and federation, while N. Pašić insisted on the monarchy with the Karađorđević dynasty and centralized internal political administration of the state. Without any doubt, the question about republic or monarchy and federalization or centralization of the future state of the Yugoslavs was the crucial problem to be solved not only during the negotiations between the Yugoslav Committee and the Royal Serbian Government in Corfu in 1917 but even during the first years of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (up to June 1921). With regard to this problem, it is important to present a letter written by Giulio Gazzari, a member of the Yugoslav Committee, to the President of the Yugoslav Committee, on April 20th, 1917. In the letter, G. Gazzari emphasized that some Serbian politicians, like Protić, Nešić, and Jovanović, have an opinion that the federal principle was the best political form for the future Yugoslav state. According to the letter, even N. Pašić himself was more and more inclining to an idea of the federal form of the common state instead of the centralized one, but the heir to the throne (regent Alexander I) under the influence of the court’s camarilla preferred the centralization of the state. G. Gazzari wrote that it was the crucial reason for the heir to the throne to support the centralized form of the state during the Corfu negotiations.[54] Therefore, it comes that the strongest opponent to the federal concept of the future common Yugoslav state was a regent of Serbia, Alexander I, but not her Prime Minister Nikola Pašić.[55]

Frano Supilo was among all members of the Yugoslav Committee the strongest supporter of the idea that Croatia should have a special autonomous status within a new state. On the other hand, he was in a strong opinion that the Yugoslav state should be organized as a federal or confederate state. In contrast to the Prime Minister of Serbia, who was a strong supporter of the centralist internal organisation of the new state arguing that any kind of the inner (con)federal arrangement would finally lead to destabilization of the state structure,[56] F. Supilo became the main supporter of the idea of federalization of the country after the unification. His idea of federalism was anticipated by historical provincialism that he used as a basis for the creation of the following five federal units within a new state of Yugoslavia: 1) Serbia with Vardar Macedonia and Vojvodina; 2) Croatia with Slavonia and Dalmatia; 3) Slovenia; 4) Bosnia and Herzegovina; and 5) Montenegro. Consequently, Yugoslavia would have the inner administrative organization similar to the Dual Monarchy of Austria–Hungary after the Aussgleich (the settlement between the Austrians and the Hungarians) in 1867, with the leading role in Yugoslav politics played by the Serbs and the Croats.[57]

The Yugoslav Committee’s standpoint on the process of the unification of the Yugoslavs had as its crucial political aim to protect the Croatian national interest, as well as the interests of Croatia as a historical land with autonomous rights. F. Supilo was the most important “defender” of the Croatian national interests during the process of the unification. His main political conception was a “unity of the Croats”, or as he was saying the “western part of our people” (i.e. the South Slavs), what meant that all South Slavic lands eastward from Slovenian Alps and westward from the Drina River have to be included into Croatia within Yugoslavia. For that reason, F. Supilo requested a plebiscite about the unification with Serbia and Montenegro not only in Croatia but in all Austro–Hungarian Yugoslav provinces for “particular and political reasons”.[58] He was sure that only Bačka and South Banat would opt for Serbia, while the rest of the Yugoslav lands within the Dual Monarchy (Bosnia, Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Slavonia, Istria, and Dalmatia) would choose Croatia. The Yugoslav Committee, in contrast to the Royal Government of Serbia, supported an idea of the plebiscite as one of the most legitimate, justifiable and proper ways for the unification of the South Slavs into a common state. It meant that the Yugoslav people had to be asked to decide upon their own fate after the war.[59] For F. Supilo, an agreement about the Croatian confederate status within the future common state with Serbia and Montenegro was a starting point in the process of the creation of Yugoslavia.[60] He divided political subjects concerning the unification into two camps: 1) Croatia and 2) Serbia with Montenegro. According to him, Croatia had to have a leading political role among the Austro-Hungarian South Slavs, while Serbia had to have the same role among the Yugoslavs outside the Dual Monarchy. His demand, which became as well as the main demand by the most of the Yugoslav Committee’s members, was that the unification had to be accomplished on the equal level between Serbia’s Royal Government and the Yugoslav Committee, because, according to him, any other way of the creation of Yugoslavia would be, in fact, a domination of “the Serbo-Orthodox exclusivity”.[61] The President of the Yugoslav Committee, Dr. A. Trumbić, summarized the whole issue of the process (the way) of the unification into two points: 1) the unification could be realized either with a liberation of the Yugoslav lands in Austria-Hungary and their incorporation into Serbia or 2) it could be done with the union of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes on the equal level. The Yugoslav Committee chose the second option. However, in both options, the South Slavic lands within Austria-Hungary had to be liberated by the Serbian army.

However, from Serbia’s point of view, the main lack of such approach by the Yugoslav Committee was a very fact that either the Yugoslav Committee or the Montenegrin Royal Government in exile (in Rome) did not have a single soldier of their own to fight for the unification in comparison to Serbia’s 150,000 soldiers at the Macedonian Front in North Greece. In other words, the Yugoslav Committee required for itself an equal political position in the unification process but only Serbia had to spill over the blood of her soldiers (and civilians in occupied Serbia) for the creation of a single Yugoslav state. Serbia even succeeded finally to beat back the Croatian requirement for the federal type of Yugoslavia by nominally accepting this idea during the negotiations at Corfu but only under the condition that united Serbian federal unit within Yugoslavia would be created, that meant that the Croatian federal-territorial part was going to be composed by only one-third of the required lands by the Croats, who at any case have been well informed that Italy was willing to make a deal with Serbia about the territorial division of Dalmatia between Rome and Belgrade.

The standpoint about the way of the unification of the Royal Government of Serbia was different in comparison to the Yugoslav Committee’s one. Serbia never officially recognized the Yugoslav Committee as a representative institution of the South Slavs from Austria-Hungary. Therefore, Serbia played the role of the only representative actor of all Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes before the Entente states. Moreover, especially for N. Pašić, the Yugoslav Committee could not be an equal partner with Serbia’s Royal Government in the process of the unification because of political, moral, and military reasons. The crucial request by the members of the Yugoslav Committee that a plebiscite about the unification and state’s inner organization had to be organized was rejected by Serbia likewise the internal federalist state’s organization which was favored by the Yugoslav Committee. Particularly, F. Supilo’s idea of a federal Croat province within Yugoslavia was never accepted by N. Pašić who always was in the opinion that such Croatia would be constantly a corpus separatum and “state within the state”. The crucial aspect of N. Pašić’s policy about the process of the unification was that Serbia’s politicians should be natural representatives of all Yugoslavs before the Entente powers until the time of the final peace conference. He justified this requirement by three facts: 1) Serbia had legal Government, 2) Serbia was internationally recognized state, and 3) Serbia was allied member of the Entente bloc.

The attitude of Serbia was that if Yugoslavia was to be created, territorial borders had to be clearly defined between Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia[62] as N. Pašić wanted firstly to unify “all Serbian lands and people” within one political unit and after that to unify such territory with other Yugoslav lands into a single state. It is likely that the Royal Government of Serbia was not in principle against the federal organization of the new state but for Serbia, it was unacceptable that if Yugoslavia was to be federation, the Serbian population would be divided into several federal units. In other words, only a federal Yugoslavia with three federal units was possible: Slovenia, Croatia, and Serbia. The Serbian federal unit had to include all “Serbian people and lands”.[63] Nevertheless, at the Corfu Conference, the idea of federal organization was given up, taking into account the fact that “…when we started to make borders we understood that it was impossible”, as N. Pašić explained to the Parliament of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1923.[64] Even A. Trumbić understood that in the case of the federal organization of the new state on the national basis, a Greater Serbia (composed by all Serbs and the Serbian lands) would dominate the country that became finally the crucial reason for him to reject the federal project of Yugoslavia during the Corfu Conference.

The Corfu Declaration (July 20th, 1917) as a political compromise

The Corfu Conference was held from June 15th to July 20th, 1917 that means for more than a month. It shows both how much the conference was important and how many political solutions proposed by both sides have been different. From the side of the Yugoslav Committee as the negotiators arrived A. Trumbić, D. Vasiljević, B. Bosniak, H. Hinković, F. Potočnjak, and D. Trinajestić. At the same time, the Kingdom of Serbia was represented by N. Pašić, M. Ninčić, A. Nikolić, Lj. Davidović, S. Protić, V. Marinković, M. Đuričić, and M. Drašković.[65] The basis for discussion under the official title Provisional State until Constitutional Organization was prepared by the Close Board composed of five members who worked out drafts about the basic problems upon the creation and organization of the future state to be solved.

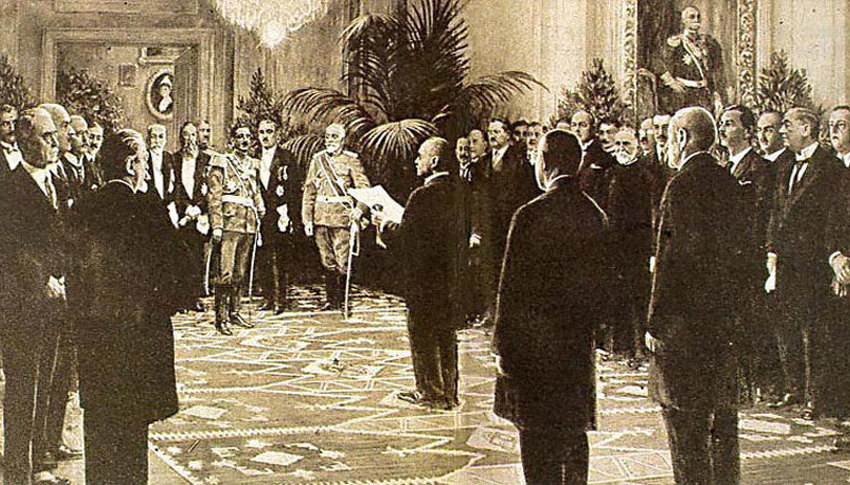

After very laborious negotiations of more than a month, both sides signed a common declaration in a form of the basic agreement upon a political form of a new state to be proclaimed at the very end of the war. The joint Corfu Declaration is the most significant legal document about the creation of a single Yugoslav state, signed on July 20th, 1917 by two representatives of the Royal Serbian Government and the Yugoslav Committee: Nikola Pašić and Ante Trumbić.[66] The declaration was composed of twelve points based on two principles: 1) the principle of national unity of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and 2) the principle of self-determination of the people. Nevertheless, the Corfu Declaration did not have a constitutional character as it just regulated only some of the most important questions of the future state. It was only “the joint statement (declaration) of the representatives of Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee with regard to the foundations of the common state and about some of its fundamental principles”.[67]

In regard to the question of the internal political-administrative organization of the future state, the most important point was that the state of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes will be a constitutional, democratic and parliamentary monarchy under the Karađorđević dynasty, “which has always shared the feelings of the nation and has placed the national will above all else”.[68] This point of the declaration was a great political victory of the Royal Government of Serbia as the idea of a republic was finally rejected. Therefore, the Yugoslav Committee accepted the new state as a monarchy. Instead of federalization of the country, the local autonomies were guaranteed and based on natural, social, and economic conditions but not on historical or ethnic principles. The two alphabets, Cyrillic and Latin, have been proclaimed as an equal in public use in the whole country likewise the Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Muslim creeds were proclaimed to be equal and their believers will have the same rights. It was proclaimed as well as that “The territory of the Kingdom will include all territory in which our people form the continuous population, and cannot be mutilated without endangering the vital interests of the community. Our nation demands nothing that belongs to others, but only what is its own. It desires freedom and unity. Therefore it consciously and firmly refuses all partial solutions of the propositions of the deliverance from Austro-Hungarian domination, and its union with Serbia and Montenegro in one sole State forming an indivisible whole” (the 8th point).[69] Obviously, this point of the declaration was, in fact, a great diplomatic victory of the Yugoslav Committee and pointed out against the articles of the secret London Treaty which was signed on April 26th, 1915. Presumably, the army of Serbia at the end of the war had to protect the South Slavic (i.e., Croat and Slovenian) lands in Dalmatia and Istria against the Italian territorial aspirations (irredenta). Finally, the deputies to the national Parliament of the new state will be elected by universal, direct, and secret suffrage. The Constituent Assembly would accept a Constitution with a numerically qualified majority. The Constitution of the Yugoslav state was going to be accepted after the conclusion of the peace treaties and it will come into force after receiving the royal sanction. “The nation thus unified will form a State of some 12,000,000 inhabitants, which will be a powerful bulwark against German aggression and an inseparable ally of all civilized States and peoples” (the 12th point).[70]

The most important victory of the Yugoslav Committee (i.e., the Croat and Slovene politicians as the representatives of the South Slavs from the Dual Monarchy) against the Royal Government of Serbia at the Corfu Conference was the fact that Serbia did not get any privileged position or the veto rights in the new state as it was, for instance, the case with Prussia in unified Germany after 1871. The Kingdom of Serbia even, for the sake of the creation of a single Yugoslav state, canceled its own internationally-recognized independence, denied her democratic Constitution, national flag, and other national symbols.[71] N. Pašić denied “liberating” role of Serbia during the war and succeeded only to impose the monarchical type of the state with the Karađorđević’s dynasty[72], i.e., under the realm of the Regent-King Alexander I from Montenegro.

Nevertheless, it is a false interpretation of the Corfu Declaration by some Yugoslav and international historiographers that by this declaration Serbia received rights to annex Austro-Hungarian territories settled by the South Slavs (the Yugoslavs): Slavonia, Banat, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Dalmatia.[73] However, according to the text of the Corfu Declaration, the ethnic Serbs from the Dual Monarchy were de facto left to be united with Serbia and Montenegro into a single Yugoslav state by Zagreb as a political center of the Yugoslav lands of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Therefore, on October 29th, 1918 it was proclaimed in Zagreb the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs pretending to have a legal competence over all Yugoslav lands of the Dual Monarchy. This state was proclaimed de facto as a Greater Croatia with a Croat national and historic flag as the state’s symbol (red-white-blue horizontal tricolor). However, the ethnic Serbs were a simple majority in the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs with the capital in Zagreb – a state declared to exist on the Croat ethnic and historic rights formulated by the Croatian Party of Rights in the mid-19th century. Nevertheless, the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs were internationally recognized only by the Kingdom of Serbia in the spirit of the Corfu Declaration when Serbia’s Regent Alexander I read in Belgrade on December 1st, 1918 a letter of answer to the official delegation which came from Zagreb to the act of Proclamation by the National Council in Zagreb of the unification of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs with “the Kingdom of Serbia and Montenegro”.[74]

Finally, the Corfu Declaration accepted an idea of “compromised national unitary state of the three-names nation: the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes”.[75] It was the main reason why the name of Yugoslavia was rejected and instead of it, the official name of the new state was proclaimed to be the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[76]

Conclusions

- The 1917 Corfu Declaration was a joint pact between the Royal Government of Serbia and the Yugoslav Committee for the sake of the creation of a single Yugoslav national state under the name of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The Corfu Declaration was a basis for the proclamation of such a state at the end of the First World War and for its first Constitution in 1921.

- The crucial problems in relation to the internal state’s organization have not been solved by the Corfu Declaration. They were left to be finally solved for the time after the war, by the Constituent Assembly, which should be elected by the universal suffrage.

- All Constituent Assembly’s decisions should get the royal sanction in order to be verified. This meant that the monarch had the right of the veto.

- For both the Yugoslav Committee and the Royal Government of Serbia the most urgent aim was to issue a common declaration concerning the creation of a single (unified) South Slavic state in order to try to protect the Yugoslav (mainly Croatian and Slovenian) lands from the Italian territorial aspirations. Therefore, some of the most significant questions with regards to the internal state’s organization could wait to be resolved after the war and especially during the Peace Conference when the state’s borders would be finally fixed.

- The Italian territorial aspirations at the Balkans during the First World War were the most important reason for a convocation of the Corfu Conference. It can be seen from the telegram sent by J. M. Jovanović to the Regent Alexander I Karađorđević just after the publishing of the declaration, in which Jovanović noticed that the time for its issuing was chosen accurately – when the Italians came to the conferences convoked in Paris and London.[77]

- Division over opposing views between the Royal Serbian Government and the Yugoslav Committee on the unitary or federalist form of the internal-administrative constitutional arrangements reflected, in fact, opposite views about the national question.

- Since it was impossible to overcome different standpoints during the conference, an agreement was reached on the necessity for the state’s unification in the form of a monarchy and on the compromise variation of unitarianism, whereas the question of the internal-administrative organization of the state was put off for the future.[78]

- The Corfu Declaration professed the right of free self-determination as the focal war-goal and requested, at the same time, in the name of such right that the Yugoslav nation be free of any foreign occupation and unified in a single national, free, and independent state. It meant that all territories inhabited by the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenians had to be subject the principle of nationality what implied two focal facts: 1) that Yugoslavia would be founded on the free will of national representatives of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenians; and 2) that it did not imply the annexation of the Yugoslav territories from Austria-Hungary by Serbia.

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirovic 2019

[1] See the map in [G. Barraclough (ed.), The Times Atlas of World History, Revised Edition, Maplewood, New Jersey: Times Books Limited, 1986, pp. 264−265].

[2] K. W. Treptow (ed.), A History of Romania, Iaşi: The Center for Romanian Studies−The Romanian Cultural Foundation, 1996, pp. 384−389.

[3] On the Great War, see: H. Strachan, The First World War, New York: Viking Penguin, 2004; P. Hart, The Great War, 1914−1918, London: Profile Books Ltd, 2013; G. Wawro, A Mad Catastrophe: The Outbreak of World War I and the Collapse of the Habsburg Empire, Basic Books, 2014; W. Philpott, War of Attrition: Fighting the First World War, Overlook, 2014.

[4] Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca (Kraljevina SHS).

[5] S. Trifunovska (ed.), Yugoslavia Through Documents: From its creation to its dissolution, Dordrecht−Boston−London: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1994, pp. 151−160.

[6] For instance: B. Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988, I, Beograd: NOLIT, 1988, p. 26; В. Ћоровић, Наше победе, Београд: Култура, 1990, p. 141; B. Petranović, M. Zečević, Agonija dve Jugoslavije, Beograd−Šabac: Zaslon, 1991, p. 14; К. Елан, Живот и смрт Александра I краља Југославије, Београд: Ново дело, 1988, p. 27.

[7] P. R. Magocsi, Historical Atlas of Central Europe, Revised and Expanded Edition, Seattle−University of Washington Press, 2002, p. 153.

[8] According to the French writer and good friend of Alexander I, Claude Eylan, the King of Yugoslavia identified himself as a Montenegrin (K. Елан, Живот и смрт Александра I краља Југославије, Београд: Ново дело, 1988, p. 27). For the matter of fact, he was born in the capital of Montenegro – Cetinje on December 17th, 1888 at the court of the Prince of Montenegro. From the mother side (Zorka), his origin was comming from the ruling dynasty of Montenegro as his mother was a daughter of the Prince of Montenegro – Nicholas I [С. Станојевић, Сви српски владари. Биографије српских (са црногорским и босанским) и преглед хрватских владара, Београд: Отворена књига, 2015, p. 158]. About the life and death of Alexander I of Yugoslavia, see: C. Eylan, La Vie et la Mort D’Alexandre Ier Roi de Yugoslavie, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1935.

[9] Before December 1st, 1918, Serbia was already united with Montenegro, Vojvodina (a southern region of ex-Hungary) and the biggest part of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Б. Глигоријевић, Краљ Александар Карађорђевић, 1, Београд: БИГЗ, 1996, p. 441).

[10] E. Milak, Italija i Jugoslavija 1931−1937., Beograd: Institut za savremenu istoriju, 1987, pp. 22−24.

[11] Aрхив Србије, Београд, МИД КС, Политичко одељење, “Наша нота поводом прокламације италијанског протектората над Албанијом“ – Никола Пашић, 30. мај 1917. г. (old style), p. 182.

[12] Aрхив Југославије, Београд, Збирка Јована Јовановића Пижона, 80-9-44.

[13] Aрхив Југославије, Београд, Канцеларија Њ. В. Краља, Ф-2.

[14] Italian claims on both Istria and Dalmatia were strongly based on Italian historic and ethnic rights. On this issue, see: L. Monzali, The Italians of Dalmatia: From Italian Unification to World War I, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

[15] Aрхив Југославије, Београд, Канцеларија Њ. В. Краља, Ф-2.

[16] M. Zečević, M. Milošević (eds.), Diplomatska prepiska srpske vlade 1917 (Dokumenti), Beograd: Narodno delo−Arhiv Jugoslavije, without year, p. 321. However, according to Đ. Đ. Stanković, the Prime Minister of Serbia invited Dr. A. Trumbić to come to the Corfu island not with four but with five members of the Yugoslav Committee [Ђ. Ђ. Станковић, Никола Пашић и југословенско питање, II, Београд: БИГЗ, 1985, p. 160].

[17] According to J. Woodward and C. Woodward, by this treaty the Entente in return for Italy’s entrance to the war on their side assigned to Rome the following territories: Gorizzia/Gradisca, Trieste, Carniola, Istria and part of Dalmatia with most of its islands; with the exception of the city of Trieste (J. Woodward, C. Woodward, Italy and the Yugoslavs, Boston, 1920, pp. 317− 320).

[18] On the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, see: M. MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World, Random House, 2007; D. A. Andelman, A Shattered Peace: Versailles 1919 and the Price We Pay Today, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008; N. A. Graebner, Edward M. Bennett, The Versailles Treaty and Its Legacy: The Failure of the Wilsonian Vision, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

[19] After the Second World War, a new Communist Government of the socialist and federal Yugoslavia proclaimed an additional three South Slavic ethnolinguistic nationalities: the Macedonians, Muslims, and Montenegrins. For that reason, the country was re-arranged into the six socialist republics. See: J. B. Allcock, Explaining Yugoslavia, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. After 1945, socialist Serbia was deprived of the trans-Drina territories populated by Serbian majority but received two autonomous (separatist) provinces – Vojvodina and Kosovo-Metochia [Ч. Антић, Српска историја, Београд: Vukotić Media, 2019, p. 227].

[20] А. N. Dragnich, Serbia, Nikola Pašić and Yugoslavia, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1974, pp. 112−113; М. Екмечић, Ратни циљеви Србије 1914, Београд: Просвета, 1990, pp. 354−355.

[21] В. Вучковић, „Из односа Србије и Југословенског Oдбора“, Историјски часопис, vol. XII−XIII, Београд, 1963, pp. 345−350.

[22]A. Н. Драгнић, Србија, Никола Пашић и Југославија, Београд: Народна радикална странка, 1994, p. 112

[23] J. M. Joвановић, Стварање заједничке државе СХС, III, Београд: 1928, p. 47. About the Eastern Question and Russia, see in [Ф. И. Успенски, Источно питање, Београд−Подгорица: Службени лист СЦГ−ЦИД, 2003].

[24] See, for instance: A. Von Bulmerincq, Le Passe De La Russie: Depuis Les Temps Les Plus Recules Josqu’a La Paix De San Stefano 1878, Kessinger Publishing, 2010.

[25] On the Bulgarian war aims during the Great War, see: Ž. Avramovski, Ratni ciljevi Bugarske i Centralne sile 1914−1918, Beograd: Institut za savremenu istoriju, 1985.

[26] On the Russian policy and diplomacy at the Balkans in 1914−1917, see the memoirs of the Russian ambassador to Serbia – Count Grigorie Nikolaevich Trubecki: Кнез Г. Н. Трубецки, Рат на Балкану 1914−1917. и руска дипломатија, Београд: Просвета, 1994.

[27] About the truth, blunders, and abuses upon the Greater Serbia, see: В. Ђ. Крестић, М. Недић (eds.), Велика Србија: Истине, заблуде, злоупотребе. Зборник радова са Међународног научног скупа одржаног у Српској академији наука и уметности у Београду од 24−26. октобра 2002. године, Београд: Српска књижевна задруга, 2003.

[28] М. Радојевић, Љ. Димић, Србија у Великом рату 1914−1918, Београд: Српска књижевна задруга−Београдски форум за свет равноправних, 2014, p. 250.

[29] Đ. Đ. Stanković, Nikola Pašić, saveznici i stvaranje Jugoslavije 1914−1918, Beograd, 1984, 183−215.

[30] About this issue, see more in [Д. Јанковић, Југословенско питање и Крфска декларација 1917. године, Beograd, 1967].

[31] On this issue, see more in [M. Bulajić, Ustashi Crimes of Genocide. The Role of the Vatican in the Break-up of the Yugoslav State. The Mission of the Vatican in the Independent State of Croatia, Belgrade: The Ministry of Information of the Republic of Serbia, 1993].

[32] On the relations between N. Pašić and A. Trumbić, see in [D. Djokic, Pašić and Trumbić: The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, London: Haus Publishing, 2010]. On N. Pašić’s relations with the Croat politicians in 1918−1923, see in [Ђ. Ђ. Станковић, Никола Пашић и Хрвати, 1918−1923, Београд: БИГЗ, 1995].

[33] About the political ideology of the Croatian Party of Rights, see in [M. Gross, A. Szabo, Prema hrvatskome građanskom društvu, Zagreb, 1992, pp. 257−265].

[34] A. Trumbić, “Nekoliko riječi o Krfskoj deklaraciji”, Bulletin Yougoslave, No. 26, November 1st, 1917, Jugoslavenski Odbor u Londonu, Zagreb: JAZU, 1966, p. 167.

[35] G. Barraclough (ed.), The Times Atlas of World History, Revised Edition, Maplewood, New Jersey: Times Books Limited, 1986, p. 258.

[36] On the February Revolution and the Provisional Government in St. Petersburg, see in [J. Anisimov, Rusijos istorija nuo Riuriko iki Putino. Žmonės. Įvykiai. Datos, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras. Vilnius, 2014, pp. 327−330].

[37] The main figure in the 1917 February (March) Revolution in Russia was Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky (1881−1970). He was a member of a moderate socialist party – Trudoviks. In the new Russian Provisional Government, he became a Minister of Justice and later a Minister of War. He was born in Ulyanovsk like Vladimir Ilich Lenin and was of the same ethnicity as Lenin was. We have to keep in mind that beyond the 1917 February (March) Revolution in Russia was the British diplomacy, while beyond the 1917 October (November) Revolution, led by V. I. Lenin, was, in fact, Germany.

[38] About the first serious Serbian plan to call Russia to become the protector of a united national state of the Serbs, see: Vladislav B. Sotirović, “The Memorandum (1804) by the Karlovci Metropolitan Stevan Stratimirović”, Serbian Studies: Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies, vol. 24, № 1−2, Bloomington, 2010, pp. 27−48.

[39] A. Mandić, Fragmenti za historiju ujedinjenja, Zagreb, 1956, p. 77.

[40] Jugoslavenski Odbor u Londonu, Zagreb: JAZU, 1966, p. 173.

[41] F. Šišić, Dokumenti o postanku Kraljevine Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, 1914−1919, Zagreb 1920, p. 94; B. Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988, I, Beograd: NOLIT, 1988, p. 18.

[42] A. Н. Драгнић, Србија, Никола Пашић и Југославија, Београд: Народна радикална странка, 1994, p. 128.

[43] М. Радојевић, Љ. Димић, Србија у Великом рату 1914−1918, Београд: Српска књижевна задруга−Београдски форум за свет равноправних, 2014, pp. 250−251.

[44] Aрхив Југославије, Београд, Канцеларија Њ. В. Краља, Ф-2.

[45] Aрхив Југославије, Београд, Збирка Јована Јовановића Пижона, 80-9-44. Esad-Pasha was an Albanian feudal lord and politician who sided on the Serbian side during the First World War.

[46] Aрхив Југославије, Београд, Канцеларија Њ. В. Краља, Ф-2.

[47] The Royal Government of Serbia was treating the Yugoslav Committee in London as its propaganda agency in Europe for the very reason that the committee was mainly financially supported by Serbia.

[48] Ђ. Ђ. Станковић, Никола Пашић и југословенско питање, II, Београд: БИГЗ, 1985, p. 181.

[49] Д. Јанковић, Југословенско питање и Крфска декларација, Београд, 1967, p. 197.

[50] For instance, state’s cultural policy between 1918 and 1941 was put within such identity frame (see: Љ. Димић, Културна политика у Краљевини Југославији 1918–1941, I–III, Beograd: Стубови културе, 1997).

[51] B. Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988, I, Beograd: NOLIT, 1988, p. 17. The Croatian historians Dragutin Pavličević and Ivo Perić claim that all Serbia’s Governments during the last hundred years (with N. Pašić’s war-time Government on the first place) had for their ultimate national goal a creation of a Greater Serbia (D. Pavličević, Povijest Hrvatske. Drugo, izmijenjeno i prošireno izdanje, Zagreb, 2000, p. 307; I. Perić, Povijest Hrvata, Zagreb, 1997, pp. 209–232).

[52] At that time the overwhelming majority of the citizens of Montenegro were declaring themselves as ethnolinguistic Serbs. About the ethnic and national identity of the Montenegrins, see: M. Glomazić, Etničko i nacionalno biće Crnogoraca, Beograd: Panpublik, 1988.

[53] During the war, Serbia lost more than ¼ of her pre-war population [М. Радојевић, Љ. Димић, Србија у Великом рату 1914−1918, Београд: Српска књижевна задруга−Београдски форум за свет равноправних, 2014, p. 285].

[54] Arhiv JAZU, Zagreb, Fond Jugoslavenskog Odbora, fasc. 30, doc. No. 29.

[55] However, for the federal form of a new state did not exist a great interest even among many members of the Yugoslav Committee for the very reason to avoid the clash between two opposite concepts of Yugoslavia’s federalization: a Greater Croatia vs. a Greater Serbia. Therefore, according to A. Trumbić’s biographer, Ante Smith-Pavelitch, even A. Trumbić was not so ardent advocate of the federalization of the Yugoslav state during the war-time for the very reason that N. Pašić could use this idea in order to promote and finally create a Greater Serbia as a single and the biggest federal unit (out of three) of Yugoslavia. Subsequently, a Greater Serbia, as one of three federal units of Yugoslavia, would be a dominant political factor in the country [Ђ. Ђ. Станковић, Никола Пашић и југословенско питање, I, Београд: БИГЗ, 1985, p. 213].

[56] “Белешке са седнице Крфске конференције”, Нови живот, IV, 5. јун 1917. г., Београд (June 5th, 1917, Belgrade), 1921.