Views: 1686

What is the European Union

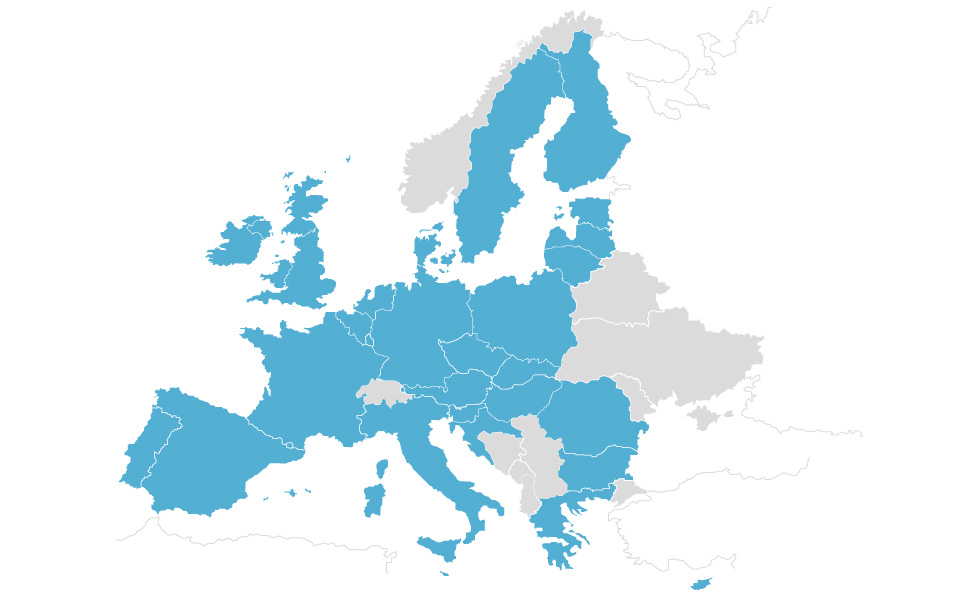

In Europe, regionalization after WWII is taking the form of a gradual process of integration that was leading to the creation of the European Union (the EU) which is a collaborative association of some of the European states previously known as several different communities. Since agreeing at a summit meeting in December 1991 in the city of Maastricht in the Netherlands to move beyond a custom union and common market towards full economic and monetary union[1] (up to that time the EU was similar to the European Free Trade Association – the EFTA),[2] the association of the Member States (currently 28) is now referred as the European Union which is the world’s most highly integrated economic bloc.[3] The EU was initially a purely West European creation between the original Six Member States (E6) born out of the desire for a historical reconciliation between France and Germany in a context of ambitious federalist design.[4] Nevertheless, from very limited start, both in terms of membership and in terms of scope, the EU became gradually developed to become today an important political, economic, financial, and institutional actor in global politics whose activities have significant impact, both in external and internal affairs. This gradual process of European integration is taken place at different levels. The start was the signature and reform of the basic EU’s treaties as the result of Inter-governmental Conferences, where the representatives of national Governments negotiate the legal framework within which the EU’s institutions are operating. Such treaty changes require ratification in each Member State. Nonetheless, within such framework, the institutions are given considerable powers to adopt decisions and manage policies, regardless of the fact that the dynamics of decision-making differ very much across different arenas. In some areas, a Member State was obliged to accept decisions which are basically imposed on it by the qualified majority of the Member States, but in some other areas it may be able to use a veto right and, therefore, to block decision.

The EU is created by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty that was made up of three pillars:

- The European Community (the EC), whose decisions were created by the European Commission, the European Council, and the European Parliament. Those decisions were guarded by the European Court of Justice.

- The Common Foreign and Security Policy, which is founded on the basis of intergovernmental cooperation in the European Council.

- Justice and Home Affairs, subject to decisions taken by the European Council too.[5]

However, the fundamental absence of the EU’s institutions in the decision-making procedure of the second and the third pillars, in fact, led to their visible ineffectiveness. As a consequence, the 1997 Amsterdam Treaty transferred several crucial policies on immigration and border control from the third to the first pillar. Furthermore, the second pillar was at the 2003 Intergovernmental Conference made stronger by the formulation of comprehensive policy goals in the European Security Strategy. A European Defence Agency was created in 2004 for the formal sake to co-ordinate military crisis-management, but, in fact, the EU is warmongering and fuelling such conflicts like in South Serbia’s province of Kosovo-Metochia or in Donbas region. Therefore, the real task of this agency is to maintain the EU’s geopolitical interest in the continent being a part of NATO’s strategy in its war against Russia.

From the very beginning of its existence in 1992, the EU is faced with several major problems, one after another. Since 1989, among others, Europe has experienced the German (re)unification followed by the post-Communist transitions, economic and financial problems, a migrant crisis, and finally up to now the referendum for continued or not EU’s membership in the UK which had as a consequence the Brexit. In the current political situation in direct relation to the British Euroscepticism which resulted in the Brexit, the question of survival of the EU’s project already became the cancer problem in a global perspective. Fears and/or hopes, that one will witness the decay and final dissolution of the EU and its project of the European unification are surely taking on momentum. Today, with the prolonged Greek crisis, the Brexit vote, the increased popularity of Marie Le Pen in France and the rise of German Alternative for Germany’s party, there are now consolidated political bloc acting against the political unity of and trust in the project of Europeanization within the framework of the EU – a project which is unclear from the very beginning of the integration in the 1950s. As a consequence, today is existing tremendous distrust into the project as the European integration resulted in a complicated framework of rules, legislation, and regulations with institutional irresponsibility followed by incomprehensible bureaucratic machinery.[6] It is quite natural that people fear and dislike something that is often seen as unfair through the wrong moves and action of those who are in (uncontrolled) political power[7] as it was recently the case with all Socialist countries in East Europe.

In order to understand the integration process within the EU’s framework, it is necessary to take account of the role which is played by both Member States and supranational institutions. We have not to forget that the Member States are not only represented by their national Governments, since a host of state, non-state, and trans-national actors participate in the process of domestic preference formation or direct representation of interests in Brussels. But the relative openness and transparency of the EU’s policy process and decision-making procedure, in fact, means that different political actors or economic-financial groups are trying to significantly influence the EU’s decision-making as many of them are feeling that their position is not sufficiently represented by national Governments. That is exactly the reason together with the complexity of the EU’s institutional and bureaucratized machinery why the EU is seen by many Eurosceptics as a system of multilevel governance, involving a plurality of actors on different territorial levels as they are supra-national, national, and sub-national which can easily harm the principle of national sovereignty. In essence, the politics of above the level of nation-states are seen as the most significant and influential at the European level and, therefore, supra-national governmental bodies of the EU are regarded as the most dangerous for national sovereignty and independence.[8]

The foundations of the Euroscepticism

Nobody is going to be surprised with the term “Euroscepticism” concerning the idea, concept, practice, and enlargement of the European Union as the term has organically entered several decades ago both the mass media and scientific literature. As a matter of fact, the number of Eurosceptics is growing to such extent that even entire political parties or movements joined this camp. Interestingly, the Eurosceptics could be found across all EU’s countries as well as in the rest of historical-geographical Europe. Their success at the European parliamentary elections in May 2014 and May 2019 proved that the Euroscepticism needs the most serious attention from several standpoints: political, cultural, social, ideological, and even historical. Here, the fundamental questions are: What do the Eurosceptics want and what stands behind this phenomenon?

In essence, the Euroscepticism as political expression means the skeptical or/and negative attitude to the integration processes (“Europeanization”) of the Old Continent within the framework of the European Union as a geopolitical project.[9] It became today widely used concept, term, and phenomena to describe the strongly critical and/or even nihilistic attitude towards the project of the EU. Besides the common dislike for the integration processes, the Eurosceptics stand, in general, against the EU’s particular projects, specifically against the introduction of a single currency, the European Constitution, the bureaucratized, centralized, non-elective and non-responsible supra-governmental institutions in Brussels (the European Council and the European Commission), a single citizenship, and the project of federalization. Contrary to the idea of a supranational EU, the Eurosceptics across Europe support the independence of national states and their sovereign rights and voice the concern that further integration (the eastward enlargement) will be irreversibly detrimental for their national states and it will finally result in the loss of the right to self-determination. For instance, one of the most senior politicians who spoke against the EU was the President of the Czech Republic, Vaclav Klaus, who repeatedly warned his nation that after accession the Czech Republic would cease to exist as a sovereign state.[10] However, at the same time, Vaclav Klaus as well as argued that the Czech Republic do to the current geopolitical circumstances, in fact, did not have a real choice over the issue of the EU’s accession, and that it had to join the EU for the reason if it did not want to be left isolated both economically and politically.

The political forces labelled as Eurosceptics on the extreme end, tend to oppose all the aspects of the EU and the European integration as its project, emphasizing a patriotic and democratic need to reclaim independence and the country’s exit from the club of the EU which is in many Eurosceptic cases seen as a West Capitalistic USSR. The Eurosceptics can be conditionally divided into two groups: 1) those who entirely reject the integration up to the total exit from the Union (the Hard Euroscepticism) and 2) those who criticize the integration for different causes like economic colonialism, nation-state’s sovereignty, lack of democracy (democratic deficit),[11] etc. and call for the EU’s internal reformation but without exiting it (the Soft Euroscepticism). However, geographical division of these two types of Euroscepticism is quite visible as the Hard Euroscepticism is common in more westward located countries (for instance, the Brexit case) where the voices requiring either “exit” of their national states from the EU or even the end of the EU. The Soft Eurosceptics are more eastward located who require just the internal institutional and legal reconstruction of the EU but not “exit” of their national states. The reason for such geographical Eurosceptic division is, in fact, of the economic-financial nature as West European states (the West Donor States) are feeding those on the East (the East Parasite States).

The Eurosceptics coming from East Europe are realistically scared of economic hardship and economic-financial neocolonialism, high unemployment, massive emigration and the EU’s legislation that land and real estate property are going to be sold off to foreigners (from West European states).[12] The farmers were among the most strident Eurosceptics for the very reason as they well knew that they would not be able to compete with their Western counterparts in the EU.[13] It is an objective truth that several million farms in East Europe are small and poorly equipped to deal with competition from West Europe. In fact, after the accession, East European farmers initially were handicapped by the EU’s system of direct farm subsidies especially the richest of the candidate states who joined the EU in 2004 (Slovenia and the Czech Republic) stand to gain the least from the EU’s economic package.

In general, five focal factors appear to have the most influence on the rise of Eurosceptics across Europe during the last two decades who are questioning whether the benefits of membership outweigh the burdens[14]:

- The immediate cost of the accession for the taxpayers from accepted countries.

- The fear among the people from the EU’s 15 Old Member States (those who signed the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 and those who joined the EU in 1995) over the massive invasion of the cheap labor force from the New Member States (those who joined the EU from 2004 onward).

- The permanent tensions over the post-WWII final settlements with neighboring Germany and to a certain extent with Austria.

- The fear of the consequences of the mandatory introduction of a single EU’s currency – the Euro.

- The trepidation that East European states with a rising budget deficit (for instance, Poland, the Czech Republic or Hungary) will be forced to cut back on their expenditure for health, education, social security, and other welfare policies what in reality finally happened after the accession.

It is impossible to talk about Euroscepticism as a fully-fledged political ideology as different political forces may attach different meanings to this idea and remain Eurosceptics at the same time being major political rivals. Any political spectrum party can for different reasons have both the European integration opponents and proponents. However, in practice, the Euroscepticism mainly exists and develops within the patriotic-conservative and ultraconservative ideology framework which is conspicuously reflected at an all-European level. It is Euroscepticism that serves an ideological cooperation ground for a range of right-wing parties within the EU which are getting more and more popular trans-European support. In this context, it can be defined as an important transnational aspect of the modern European conservatism which is, in essence, anti-federal. For instance, the pro-Brexit British politicians traditionally are deeply skeptical about any steps toward a political federation of the EU and they insist, for instance, on the right of any member to veto decisions on foreign policy and taxation – two areas that cut to the very core of national sovereignty.[15] Such anti-federalist attitude is at the same time and anti-German approach concerning the Europeanization as (re)united Germany does not have any reason to fear federalization project in which it would be the biggest and strongest constituent part. The 1992 Maastricht Treaty unlocked the door to the federalization process of the EU but it did not open it. We saw that the ratification debates brought anti-federalist Eurosceptics on the political scene and revealed much popular dissatisfaction with the complexity and stupefying language of the treaty followed by popular resistance to the idea of an economic and monetary union (the EMU).

The Euroscepticism made quite a statement during the all-European constitutional project discussion in 2004‒2005, when the majority in a number of the EU’s countries (France, Netherlands, the UK, Denmark, Poland) voted against it. The ensuing crisis ended with the signing of the Lisbon Treaty in 2007 (enforced in 2009) which has as its ultimate goal to transform the EU into supranational state but for such state to exist there would have to be a leadership capable of inspiring loyalty in the hearts of the EU’s citizens of every nationality but how effectively or authoritatively a future EU’s super-leaders can speak and do for the EU under all political and other circumstances is a wide-open question.

The problem of accountability of the EU’s decision-making bodies became, in fact, one of the focal issues to be criticized by the Eurosceptics who called it in to the question in the context of the EU’s attempt to introduce a Constitution, which began in 2004. Even the Eurobueraucrats openly recognized democratic deficit in the EU. For example, in 2001, the EU’s heads of governing bodies on the meeting in Laeken in Belgium declared that the EU’s citizens are calling for a clear, open, effective, and democratically controlled approach by the governing institutions of the EU. For that reason, it has established a formal and up to now not so functional convention in order to get and deal with proposals for the EU’s Constitution. This convention had as its focal three aims:

- Clarify where power resides, by defining powers of different EU’s decision-making bodies.

- Identify the rights of citizens in relation to the existing powers.

- Provide “an indication of purpose, a rallying cry for the citizen”.[16]

A new wave of the Euroscepticism

A new wave of Euroscepticism started in connection with the global economic crisis in 2008 when for the next several years Europe had been living in social and economic shocks which piled up on the crisis phenomena in the political system. The global economic crisis shocked the very basis of the EU’s socio-economic development model and became the foundations for the new scepticism about the benefits of the EU’s membership. Even in the format of the European Single Market (the ESM),[17] the EU’s Member States have failed to overcome the lag behind the chief competitors (the USA and Japan) so far in terms of economic development and its quality as well as science, machinery, and defense. The plans of becoming the most competitive region in the world and “a knowledge-based society that eradicated poverty”, by 2010, turned out to be unfulfilled and even unthinkable. Certainly, when the economy is unstable, the public opinion is critical and this leads to the growth of critical-sceptic tendencies followed by the attempts to review what used to be viewed up to that time positively and/or advanced.[18]

The Euroscepticism’s growth was primarily reflected in the harsh criticism on the EU’s economic policy and its supra-governmental bodies. Focusing on the “Euro-bureaucrats”, the Eurosceptics are rightly claim against them several practices: making insufficiently considered decisions, belated and unsatisfactory drafting of the legislative acts and other documents, lacking sense of moderation in the regulatory decisions and their bureaucratic nature, non-transparency, the secrecy of the EU bodies’ activity, their lack of proper feedback with the civil society, the drawbacks of the 2007 Lisbon Treaty hindering the decision-making by the EU’s top institutions. For instance, it is quite true that decision-making process within the EU is not transparent even to members of the European Parliament and much less to the public.[19] However, for the Eurocrats in Brussels and supra-nationalists, there is a “democratic” explanation for such democratic deficit: making decisions more transparent will further complicate already very complicated process of decision-making especially in the European Council and the European Commission. In addition, the EU’s position in the international arena also does not bode well as it steadily loses both its economic positions and political influence.

What is democratic deficit? It is perceived lack of proper democratic accountability in an intergovernmental organization that is generally held to be democratic such as the EU. As a matter of fact, about the reality of democratic deficit within the governing and institutional scope of the EU are clearly writing many academic researchers and scholars. For instance, according to Etzioni-Halevy, “European governing institutions are in constant flux and suffer from excessive complexity, fuzziness, and ambiguity of procedures”[20] which are very characterized by special Euro-jargon and the use of numerous technical terms and several hundred acronyms. In general, such democratic deficit is off-putting for the EU’s citizens and makes it difficult for them to understand what is really going on in those EU’s bodies (especially in the European Council and Commission), and what they need to actually do in order to link up with them. As a result, this problem is clearly expressed in the concept of Euroscepticism.

Undoubtedly, the EU’s governing institutions are having important functions, but the question is: how do they measure up as representative institutions of the EU’s citizens? That is, in fact, the question: how democratically accountable are they? It is not any hidden truth that since its start in 1992, the EU is tremendously suffering from what is referred to as a democratic deficit which refers to a real or perceived gap between the EU’s lofty aspirations and what the Eurosceptics say is the mundane reality. This concern stems from the very fact that while some of the EU’s governing bodies, as the Parliament, for instance, have inbuilt provisions for regularized interactions with the citizens (i.e., electoral body), there are major problems in how these arrangements work in terms of their representatives in many particular cases due to the factors which are beyond the efficient control of anyone. The Eurosceptics are right to claim that in the EU (like in the NATO as well, for instance), do not exist a real provision for any significant public interaction with (super)power institutions or/and with senior policymakers.[21]

All this encourages the growth of the anti-European resentment as according to the opinion by many citizens, the EU is not what it used to be and does not provide adequate protection for its subjects. For instance, the research data at Eurobarometer in November 2012 suggest that the EU’s image as a governing structure since 2007 till the poll date fell by 21%; if at that date half of the respondents supported the integration, this number is not higher than 31%. The other 28% took a sharply negative approach with approximately 60% of the citizens generally expressed their distrust for the EU as a functionalbe and beneficiary institution. The opinion poll in the biggest EU’s countries (April 2015) showed that ever more people considered that separately their nations could have dealt with the economic challenges much better in comparison to the EU. More precisely, the EU was at that time distrusted by 42% in Poland, 53% in Italy, 57% in France, 69% in Germany and the UK, and 72% in Spain.

It is remarkable that besides the growth of the Euroscepticism, the traditional political parties in many European countries downplay their European enthusiasm being the Member States or not. The ideological orientation of big political parties in seven European countries (the UK, France, Germany, Netherlands, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland), showed a shift from the pro-European positions towards forms of the Euroscepticism. There was quite a distinctive ideological division at separate parties’ level: the center-left and liberal parties are more supportive of the pro-European positions than the center-right parties. The most consistent proponents of the Euroscepticism turned out to be the British Conservative Party, the Italian political alliance “The Freedom People” and the Bavarian Christian-Social Union. These parties do not oppose their countries’ membership in the EU, but their adherence to the “soft” Euroscepticism’s ideas suggests that the latter can be considered a significant aspect of the modern conservative ideology in a number of the European countries. However, big center-right parties do not usually declare their adherence to the principles of the Euroscepticism in their documents. The rightist and ultra-rightist political actors, on the contrary, openly oppose their countries’ EU membership and the further development of the European integration within the EU. Such growing tendency suggests that today being excessively pro-European is out of fashion and can be even politically unprofitable. This was proven during the 2013 EU budget discussions when many Member States opposed the increase of all-European treasury out of concern that such funds redistribution in the EU’s favor would eventually turn into the voter loss for their leaders both at the national and the EU’s elections.

Currently there are not too many big anti-integration parties at the political arena, however, the small ones which oftentimes do not have representatives at the national Parliaments can have their word not only through the mass media but also through the all-European platforms, as one instance is the European Parliament. A remarkable example to this can be the UK’s Independence Party (the UKIP) which won 14 places in this EU’s institution in 2009 – more than the Liberal Democrats and as much as the Labor Party. Two super-national Eurosceptic alliances first joined the European Parliament formed in 2009, which proved the abovementioned tendency. The most radical of these alliances was the group Europe for Freedom and Democracy consisting of 34 MPs from 9 countries: the UK, Italy, France, Greece, Denmark, Lithuania, Netherlands, Slovakia, and Finland. The core of the party was made up of the MPs from the UKIP and the Italian Northern League. Despite the fact that the alliance members, except the British, did not support their countries’ withdrawal (exit) from the EU, it was Euroscepticism that became the uniting ideology for this fraction. In general, its representatives demanded to change the EU’s configuration, expand the rights of big regions, review the immigration policy towards hardening up to the compulsory deportation of the immigrants out of the EU. The second Eurosceptic alliance, the European Conservatives and Reformists fraction (54 MPs) opposes the EU’s federalization, but leaves the right for the EU’s existence in its current form and structure yet criticizes its policy. This alliance was uniting 15 representatives from the Polish parties (Right and Justice – 11 MPs, Poland Above All – 4 MPs), 9 MPs from the Czech Civil Democratic Party, and 1 MP from the Belgian, Hungarian, Latvian, Lithuanian, and Dutch parties each. Yet the core of the fraction consisted of the British conservatives (26 mandates), earlier declaring the withdrawal from the center-right European People’s Party.

The last circumstance is quite demonstrative about the evolution in one of the leading conservative parties in Europe. In the 1990s, it was on the brink of rift on the issue of deepening the European integration but the well-organized Eurosceptics succeeded in winning the future of the Conservative Party. From that point, the Tories have consistently opposed the strengthening of supra-governmental EU’s structures that could limit the sovereignty and free decision-making at the national level. During the election campaign for the European Parliament in 2004, the Conservatives defended the idea that Britain is part of Europe, yet not controlled from Europe. During the British parliamentary elections in 2010, the Tories confirmed their moderate skepticism position. The party stood up for the EU’s decentralization, more flexible EU’s policy, it declared the non-participation in the key integration directions, particularly concerning the Economic and Currency Union, reform of the basic treaty, expanding the EU’s terms of reference in legislature, social, domestic, and foreign affairs as well as in regard with the security issues.[22] At the rime, the British Conservatives mainly focused on the defense of the national interests in their election manifesto. Such a position ensured the winning of the elections and the return to power within a coalition with the Liberal Democratic Party.

Later on, the Eurozone crisis and the worsening relations between the UK and its EU’s partners caused by the different views on its further development lead to the conspicuous growth of the Eurosceptic opinions in the country which finally ended with the Brexit. Thus, the opinion poll by The Daily Mail in December 2011, as one example, suggested that 62% of the respondents supported the PMs tough stance to Brussels, while approximately 50% supported the UK’s Euroexit (known as Brexit). In spring 2013, the number of Euroexit supporters exceeded half of the respondents. At the same time, one of the leading popular responses was the willingness to stay within a more liberal institution, using the benefits of the free trade zone; in other words, to transform back the EU into a kind of the EFTA as it was from 1957 to 1967 (the European Economic Community – the EEC).[23] As a matter of fact, at the time, 62% respondents replied that their country should not help the Eurozone countries in their debt settlement.[24]

So, the Euroscepticism in the EU’s countries grew in the crisis background, which was reflected both in the opinion polls and the election results at different levels.[25] Yet the soft Euroscepticism was prevailing within the Eurosceptics, which first and foremost suggests the dissatisfaction with the Brussels bureaucracy (Eurocrats) and the need for reforms in the EU rather than the principal rejection of the authentic integration project. Both the 2015 and 2019 European Parliamentary elections proved this tendency towards the Eurosceptics’ influential growth on the political scene. However, their distinctive feature is that their vast majority represents the rightist parties: from the center-right to ultra-right. The Eurosceptics still lack unity due to different criticism motives and platforms against the EU. Two Eurosceptic fractions remained in the newly summoned European Parliament in 2015. The third was expected, based on the French National Front and the Dutch Freedom Party, but this expectation had failed and the respective MPs were listed as independent. Nevertheless, the growth of the Euroscepticism and the increasing support for the rightist political organizations in many EU’s countries means a serious turn in the conscience of many Europeans who are rejecting the Brussels’ political line, including the reluctance to defend the traditional European values of the Christian religion, family, sovereignty, democracy, and motherland.

Conclusion

The EU as a political-economic system, organization and even form of confederal state is in existence since 1992 when the Maastricht Treaty was signed on February 7. Before the EU there were three smaller communities on which foundations of present-day EU are formed called the European Coal and Steel Community (est. 1952), the European Economic Community (est. 1957), and the European Community (est. 1967). In other words, a European-wide communities existed since soon after WWII was over but, however, even after more than fifty years of the start of the realization of the (Western) idea and concept of the European integration, there were and there are quite many Europeans who are not sincerely convinced that such way of the unification of the Old Continent is a good and beneficiary idea for their nationalities.[26] The term Euroscepticism is generally used to present and understand different forms of criticism of the EU, but as well as and opposition to continued European integration within the framework of the EU including and the so-called Eastward enlargement policy and process. Usually, these two forms are coming together being colored economically and politically. Nevertheless, one of the focal and longest complains skepticism is that such kind of European integration is weakening the nation-state and consequently undermines national identity and unity. Another charge of the Eurosceptics is that the EU is not fully democratic organization, even being undemocratic, a top-down one that plays no enough attention to the actual problems, needs, and aspirations of ordinary people and that the EU’s institutions in Brussels are very bureaucratized as dominated by unelected, overpaid civil servants, in fact, politicians who are just changing chairs from one office to another one. The third concern of the Eurosceptics is about lack of real transparency in regard to the decision-making procedure in top EU’s institutions as the European Council and the European Commission. In other words, transparency is replaced by the lobbying policy.

In essence, the EU is a post-sovereign framework for the building of the supra-state with the European instead of historical-traditional national identity. As a consequence, during the last several decades political and other forms of power steadily moved away from sovereign nation-states as members of the organization to supranational bureaucratic decision-making bodies of the centralized and not controlled authorities in Brussels and elsewhere (Strasbourg, Luxemburg or Frankfurt am Main). As a result, the EU established a new form of undemocratic and non-transparent governance at an intermediate level (regional) between the global and the nation-state.

From one point of view, what is creating the EU to be unique case among all existing regional integration organizations is a fact that the EU has developed mature governing institutions and administrative bodies which make it be so far the most advanced project of regional integration all over the world. As a matter of fact, the existing stage of the EU’s development and integration is a result of a complex process since 1952 when it was developed a multifaced structure with political, economic, security and cultural goals, arrived at via a series of treaties for the sake to transform Member States into the key players in international relations. However, majority of the Eurosceptics share the same opinion that the TEU’s integration how it is outlined in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty is simply mistake[27] which is leading their nation-states into catastrophe. They also oppose the theory of The End of History[28] which posits that the USA and West Europe reached the end of history by allegedly successfully democratizing, guaranteeing human rights, achieving stability, and implementing economic liberalization. Instead of such approach, the Eurosceptics are in viewpoint that the EU is, in fact, an organization which is promulgating the so-called “enforcement terror” – economic, political, administrative, bureaucratic, and legislative terrorism carried out by the governmental bodies or government-back agencies against its own citizens.

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2019

[1] Viotti R. P., Kauppi V. M., International Relations and World Politics, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 2009, 542.

[2] The EFTA originally was founded in 1959 by the British as a counter-weight to the French-dominated the European Economic Union. Most members of the EFTA are, however, today members of the EU. The UK joined the European Community in 1973 together with Ireland and Denmark.

[3] Spiegel L. S., Taw M. J., Wehling L. F., Williams P. K., World Politics in a New Era, Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning, 2004, 695.

[4] Baylis J., Smith S., Owens P., The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, 444.

[5] Palmowski J., A Dictionary of Contemporary World History from 1900 to the Present Day, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 203.

[6] In the bureaucratic politics practice, the decision-making process is the outcome of barging among bureaucratic groups having competing interests. The final decision is an outcome of the relative power of separate bureaucratic players or of the organizations they represent. More about Bureaucratic/Organizational model of decision-making and bureaucratic politics see in [Mingst A. K., Essentials of International Relations, New York−London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004, 125−126].

[7] Bukovskis K. (ed.), Euroscepticism in Small EU Member States, Riga: Latvian Institute of International Affairs, 2016, 8.

[8] According to all Eurosceptics, national sovereignty and independence have to be in the hands of nation-state that is a form of political organization which involves: 1) A set of institutions that govern the people within a particular territory of the state, and 2) That claims allegiance and legitimacy from those governed, and from other states, on the foundation that they represent a group of people defined in cultural and political terms as a nation [Cloke P., Crang Ph., Goodwin M. (eds.), Introducing Human Geographies, Abington, UK: Hodder Arnold, 2005, 41].

[9] On the process and politics of the „Europeanization“ within the framework of the European Union, see more in: [Cini, M., Borragan, S. P. N., European Union Politics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013; Gilbert, M., European Integration: A Concise History, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2012; Hix, S., Høyland, B., The Political System of the European Union, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011; McCormick, J., Olsen, J., The European Union: Politics and Policies, New York: Routledge, 2018].

[10] Shafir M., “Analyzis: Czechs still fear fireworks mark pyrrhic victory”, RFE/RL Newsline, special issue, “EU Expends Eastward”, May 3rd, 2004.

[11] About on which democratic principles the EU has to be founded, see in [Piattoni S. (ed.), The European Union: Democratic Principles and Institutional Architectures in Times of Crisis, New York: Oxford University Press, 2015].

[12] See, for instance, the Accession Treaty of Lithuania with the European Union in 2004 [Lietuvos stojimo į Europos Sąjungą. Sutartis, Vilnius: Seimo leidykla “Valstybės žinios”, 2004].

[13] Gowland D., Dunphy R., Lythe Ch., The European Mosaic, Third Edition, Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited, 2006, 16.

[14] Magstadt M. Th., Contemporary European Politics: A Comparative Perspective, Belmont, CA: Thomson Higher Education, 2007, 46.

[15] Sovereignty is the principle of the absolute and unlimited power of the state which presupposes the absence of any higher authority in either domestic or external affairs. There are two types of sovereignty: internal and external. Internal sovereignty is a concept of supreme authority within the state’s borders, located in a body that makes decisions which are binding on all citizens, groups, and institutions within the state’s territorial borders. External sovereignty is a concept of the absolute and unlimited authority of the state as an actor in world politics. The concept, in fact, implies the absence of any higher power or authority in external affairs of the state [Heywood A., Global Politics, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 113]. In other words, sovereignty is a status of states as legal equals under international law, according to which they are supreme internally and subject to no higher external authority [Mansbach W. R., Taylor L. K., Introduction to Global Politics, New York: Routledge, 2012, 584].

[16] Bogdanor V., “Europe Needs a Rallying Cry”, The Guardian, May 28th, 2003. Nevertheless, the real progress towards the Constitution was not entirely smooth regardless of the fact that most of the EU’s the Member States ratified their nation-state’s acceptance of it by late 2009, including Ireland which firstly rejected the Constitution when the citizens voted for the issue the first time.

[17] On the ESM see in [Grin G., The Battle of the Single European Market: Achievements and Economic Thought, 1985−2016, London−New York: Routledge, 2016].

[18] The EU until the 2008 economic crisis was widely seen as a successful project in terms of how to develop regional cooperation among previously hostile regional countries. The signing of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which created the ESM, especially encouraged widespread interest in Europe’s regional cooperation with a strong belief it will bring soon fundamental benefits for the (East European) applicant and candidate states. The ESM focused attention on the success of the EU’s decades-long economic cooperation and consequent long-term regional economic growth and expected prosperity. However, as a reaction to the ESM’s project, for many other regions across the globe the EU’s economic and developmental success up to the 2008 economic crisis stimulated a wider and extra European “urge to merge”. It occurred because the ESM created and deepened competitive pressure and economic game for other regions which now they had to compete with the EU for market share for exports. As a result, national and regional economies (for instance, the NAFTA) of the globe became forced to engage themselves into serious economic competition with the EU especially with its Western Member States (former the West European Union). Especially North America and Asia-Pacific became increasingly concerned that facilitation of easier market access for the Member States within the EU itself would lead to trade diversion at the expense of their exports [Haynes J., Hough P., Malik Sh., Pettiford L., World Politics, New York: Routledge, 2013, 280]. Subsequently, the linked emergence of the so-called “Fortress Europe” or the ESM provided a new stumulant to encourage dynamic regional cooperation in regions outside the EU [Cristiansen Th., “European and Regional Integration”, Baylis J., Smith S. (eds.), The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, 495−518].

[19] Magstadt M. Th., Contemporary European Politics: A Comparative Perspective, Belmont, CA: Thomson Higher Education, 2007, 328.

[20] Etzioni-Halevy, E., “Linkage Deficits in Transnational Politics”, International Political Science Review, 23/2, 2002, 203−222, 205.

[21] Hill C., Smith M. (eds.), International Relations and the EU, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

[22] On the politics and policies of the EU, see in [Bache I., Bulmer S., George S., Parker O., Politics in the European Union, New York: Oxford University Press, 2015; Olsen J., McCormck J., The European Union: Politics and Policies, New York: Routlegde, 2018].

[23] The EEC is one of the communities established in the process of European integration after WWII. Encouraged by the economic and political success of the European Coal and Steel Community (est. 1951), the Six Member States (Benelux, West Germany, France, and Italy) signed the 1957 Rome Treaty which established the EEC, which from 1967 was transformed into the European Community (the EC). See more in [Dinan D., Ever Closer Union: An Introduction to European Integration, Lynne Rienner, 2010; Dinan D., Origins and Evolution of the European Union, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014].

[24] The single currency Euro was originally adopted in 1999. There has been a significant risk attached to the introduction of a single currency for old Member States coming from West Europe for the reason of very different economies, labor markets, and social and fiscal policy traditions compared with those countries coming from South and East Europe. On the Eurozone’s crises and perspectives, see in [Overtveld Van J., The End of the Euro: The Uneasy Future of the European Union, Chicago: An Agate Imprint, 2011; Sandbu M., Europe’s Orphan: The Future of the Euro and the Politics of Debt, Priinceton: Princeton University Press, 2015].

[25] On the crisis in European Union, see in [Castells M., et al. (eds.), Europe’s Crises, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018].

[26] Haynes J., Hough P., Malik Sh., Pettiford L., World Politics, New York: Routledge, 2013, 297.

[27] Guzzini S. (ed.), The Return of Geopolitics in Europe? Social Mechanisms and Foreign Policy Identity Crises, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 112.

[28] The original author and proponent of this theory is the US’ social analyst and political commentator, Francis Fukuyama (born 1952). He was born in Chicago, USA as the son of a Protestant preacher. Fukuyama, a Republican, was a member of the Policy Planning Staff of the US’ State Department before he became a consultant for the Rand Corporation. He became prominent as a result of his article “The End of History?” published in 1989, which he later developed into the book The End of History and the Last Man, published in 1992. He claimed that the history of ideas basically ended with the recognition of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government. However, in the book After the Neocons, published in 2006, F. Fukuyama developed a critique of the US’ foreign policy after 9/11. The theory of “The End of History” was later wrapped into the cloths of Riga Axioms – belief that the Soviet policy and the existence of the USSR was driven by ideology rather than by power [Mansbach W. R., Taylor L. K., Introduction to Global Politics, New York: Routledge, 2012, 583].

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]