Views: 1512

Belarus is a land known also as Belorussia (White Russia, Weißrussland) in East Europe which was for centuries occupied by a Polish-Lithuanian common state until it became included in Tsarist Russia in the late 18th century.[1] Belarus is facing many identity problems but the most important is the ethnolinguistic challenge to a separate Belarussian[2] national feature.

National identity

A common national identity is a focal element for the creation of a national state as without a common identity that is based on a fundamental element of group’s identity a psychological sense of common solidarity cannot be developed. However, such solidarity is a sine qua non of a voluntary decision to live with the others in the same house (i.e., a national state). In other words, the inner stability of any state primarily depends on the level of developed solidarity among the citizens. If the level of solidarity is not properly developed than the possibility for the self-destruction of the state is an open option. The recent case of ex-Yugoslavia is probably the best example of the case of self-destruction based on the lack of a common national solidarity as a common national identity of the Yugoslavs was never properly developed by state authorities. However, an example of ex-Yugoslavia’s fragile national identity is not the only in contemporary history and the present day’s politics. For instance, Europe is currently facing the same „Yugoslav syndrome“ in Spain concerning the „Catalan Question“. In East Europe, the same problems of national identity are facing Ukraine but other countries too, like Belarus.

It is commonly understood that for the creation and stable existence of the ethnic state (i.e., based on the common ethnic group identity) a native language is the most important factor as it is among all other factors of common ethnic identity the most natural one. It is given by birth and it can not disappear or be replaced. It can be suppressed (for instance, by the state authorities) but, nevertheless, it will exist in some form. Language assimilation is the most difficult and the longest process in ethnonational assimilation and it can go for several centuries and generations as, for instance, the story of old Prussian language is telling us. As the language is a focal factor of ethnonational identity, every nation pretending to exist on the ethnic (not political) basis is trying to prove to possess its own separate language which has to be internationally recognized as such. If it is done, the nation, at least according to the political philosophy of German romanticists, has natural-democratic rights to establish its own ethnonational independent state. Furthermore, the „value“ of a nation is measured according to its historically long existence of a national statehood as the „historical“ nations are more valuable in comparison to „non-historical“ nations. Those are the reasons why many national historiographies and philologies are trying to prove that their ethnic groups are historically statehood nations with a possession of a separate ethnonational language. However, in many cases it is not possible due to the lack of historical evidence in the sources and, therefore, the „academicians“ have to activate the instruments of politicized historical interpretations usually followed by the creation of the fake national historiographies. The case of Belarus is in this matter only one example among many.

According to some social investigations and research surveys in Belarus, only about 20% of the citizens are having a strong belief in the survival of Belarus identity. However, probably the most important fact is that it is possible in practice to keep Belarussian identity while speaking the Russian language as the so-called Belarussian language is more and more not a living language in the full sense of the meaning.[3] Therefore, a crux of the matter is what is a Belarussian language at all? The separate language of itself, a dialect of Russian, artificial political construction, or natural native language of Belarussian people? Getting answers to those questions are automatically solving the more important problem: do Belarussian people exist as a separate ethnic nation if they speak Russian?

Religion is in many cases one of the most fundamental factors of national identity even in some cases (like in the case of Bosnian-Herzegovinian Muslims) the fundamental one. Belarus as a country, like Ukraine, historically was situated between Russia and Poland-Lithuania and, therefore, is viewed as a borderland territory in which Christian Orthodox believers are mainly associated with the Russians while Roman Catholic Christians with the Poles. A fragile Belarus identity is, in essence, originally, framed within the framework of the Uniates – Greek Catholic believers who use Orthodox rites but recognize a dogmatic filioque and the supremacy of the Pope in the Vatican. Henceforth, Belarussian national identity is historically created as a transitional half-way between Russian Orthodoxy and Polish/Lithuanian Roman Catholicism as Belarus is a transitional land on a half-way between Orthodox Russia and Roman Catholic Poland-Lithuania, changing sides according to the historical accidents as the results of the relations between Moscow/Sankt Petersburg and Cracow/Vilnius. Nevertheless, most of those who declared themselves as Belarussian today are, in fact, the atheists or not strong believers who do not care much about organized and institutionalized religion.[4]

A geographic-political-historical location of the land in many cases determines the identity of its people which is exactly the case of Belarus. Even the ethnonym of the country is a reflection of its historical development and, therefore, for the majority of Belarus’ citizens to squeeze their national identity between Russians and Poles continues to be a historical realm of reality. However, Belarussian nationalism during the last century succeeded to rally people around several constructed markers of Belarussian identity: language, history, and ethnicity. The case of Belarussian identity is today probably the best example in East Europe of an effective policy of the creation of the national identity founded, according to Benedict Anderson, on the „imagined community“ feelings.[5] Nevertheless, the belief in a common identity of a certain group, no matter whether such belief has any foundation in the reality, has in many cases very important consequences for the creation of a national state or a political association of such imagined ethnonational community.[6]

Ethnonym

The ethnonym Belarus/Belarussia (White Russia/White Rus’) is dating back to historical sources (chronicles) by the end of the 14th century.[7] As the origin of the term is not clarified by the experts its interpretations are (mis)used by many, including and Belarussian nationalists, for political-national purposes. However, the most realistic interpretations of the origins of the ethnonym Belarus/Belorussia are:

- Belarus (White Rus’) originally meant those people of historical Kievan Rus’ who did not have obligations to pay tributes to the Tatars of Golden Orde in the 12th century as opposed to Black Rus’ who had such obligations. According to this interpretation, White Rus’ were, in essence, free Rus’ out of Tatar hegemony.

- However, Russian linguist Oleg Trubachev offered a different interpretation. According to his research results, there were three groups of the people of Rus’: a) Malaya Rus’ (Russia Minor) – the original homeland of ethnic Russians from which the expansion started; b) Velikaya Rus’ (Russia Major) – the territory of colonization from Russia Minor; and c) White Rus’ (Alba Russia) – according to the ancient color-tradition of orientation, West Russia.

There is an unprovable opinion (by Mikolo Ermalovich) that the original term for the present-day Belarus was, in fact, Litva but in the course of time, the term was usurped by a neighboring Slavs and transformed into White Russia. Nevertheless, all such hypotheses are not officially proven to become formal academic theories but they are serving well to certain national-political propaganda orientations. In other words, for the contemporary Belarussian nationalists, the etymology of the term Belarus is not connected with Russia but rather with the West and, therefore, a natural destiny of Belarus is not to be in closer political-economic relations with Russia but with Europe (NATO and European Union). Nonetheless, as a matter of historical fact, it was a clear absence of a single ethnonym for today’s territory of Belarus (and of Ukraine) before the Soviet time as, de facto, the Soviet authorities established the modern national identities of both Belarus and Ukraine.[8]

Vilnius

An idea of Belarussian ethnonational identity, as autonomous from both Russian and Polish, was born in the mid-19th century at Vilnius University in Roman Catholic Lithuania by several professors who claimed that a Belarussian self-awareness can be advocated taking into consideration literary and official state documents of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL) before the Lublin Union (signed between Poland and Lithuania in 1569). The essence of their claims was that Slavic inhabitants of GDL inherited a cultural-historical legacy and tradition to be enough different from those of neighboring Western Slavic Poles and Eastern Slavic Russians. However, as at that time the present-day territory of Belarus was part of Tsarist Russia but not of Poland (which itself at that time did not exist as an independent state) it is not so difficult to conclude that Vilnius-based idea of a separate Belarussian identity, culture, nation, and history was primarily designed as an anti-Russian political project. The idea of the Belarussian ethnic distinction from Russian national identity was further developed by the Vilnius-based literary cycle around the journal Nasha Niva (1909−1915).

It can be said that the Belarusian nation as „imagined community“ was ideologically created and politically framed in Vilnius – the capital of GDL, and subsequently, it is not of any surprise that after the dissolution of the USSR all active leaders of Belarussian (Russophobic) nationalism (like Ukrainian one) have great sympathies and open financial and political support by Lithuanian authorities. Vilnius is today transformed into both the main refugee campus for Russophobic dissidents from Belarus and propaganda center against the legitimate President of Belarus – A. Lukashenka who is demonized in Lithuania as „the last European dictator“[9] or „tyrannical President Aleksandr Lukashenka“.[10] As a matter of fact, due to the historical relations between Lithuania and Belarus, Belarussian opposition leaders consider themselves to be heirs of GDL and, therefore, using the coat of arms of it (in Lithuanian called as Vytis) as a national-historical insignia of a Belarussian nation that is also telling very much about their pro-EU/NATO’s political aspirations.[11] However, on the other hand, the majority of Belarus’ citizens consider themselves as Belarussians in geographic-political terms and/or as ethnolinguistic Russians – the fact which basically confirms their pro-Russia’s political and economic orientation.

History

Historically, as situated between Poland-Lithuania and Russia, Belarus’ Roman Catholics have been identifying themselves from ethnonational point of view as the Poles while Belarus’ Christian Orthodox believers were self-denominated as the Russians and, therefore, it was not left a room for Belarussian identity except for those who did not belong to one of these two groups. The advocates of separate Belorussian ethnonational identity have been promoting their nationalism essentially in opposition to both strong neighbors of Belarus but today Belarussian nationalism, as well as Ukrainian, is a part of well-orchestrated and sponsored Western policy of „Russophobia Vulgaris“.

In the interwar period (1919−1939) the contemporary territory of Belarus was annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union. Polish authorities at that time were recording only Christian Orthodox believers as of Belarussian ethnonational identity but not and those of Roman Catholic denomination who were considered as Poles. Such asymmetry in Polish policy of ethnonational identity was obviously going to the favor of Polonization and de-Russification of North-East Poland. At the same time, Soviet authorities were implementing a policy of Belarussification of Russian Orthodox speakers in East Belarus at that time part of the USSR in the form of the autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Belarus.

Language

All spoken Slavic languages in East Europe belong to the East Slavonic group of languages with sharing many similarities.[12] Regardless of the fact that Russian, Belorussian and Ukrainian languages are traditionally written by the Cyrillic alphabet, there are voices by Belarussian and Ukrainian nationalists to switch to Western Latin graphemes in order to be allegedly more European and lesser Russian.[13] The same voices are also trying to negate a philological fact that both Belorussian and Ukrainian languages are originating in Old Russian language like Russian itself.[14] A proto-Russian language existed from the 8th century onwards and became fragmented on the regional basis by the 13th century. A political division of Belarus and Ukraine between Poland-Lithuania and Muscovy-Russia finally broke up a linguistic unity of all East Slavs, and, therefore, Ukrainian and Belarussian languages became separately standardized in the 19th century more on political than on philological foundations. In Belarussian case, the poetry of Yanka Kupala (1882−1942) and Yakub Kolas (1882−1956) gave a basis for standardized deviation of Belorussian language from Russian, and Vilnius-based journal Nasha niva created before the WWI necessary alphabetical, orthographical and grammatical norms for the Belarussian language. This deviation was soon recognized in the Soviet Union as a separate Belorussian language, formally enough different from Russian, which was further standardized and promulgated. As a consequence of such de-Russification, according to the 1989 Soviet census, there were 77,9% of Belarus’ population who officially spoke Belarussian as their first language and only 13,2% of the local population speaking Russian as the first language. However, these official figures might be misleading in practice as, for instance, according to one survey in 1992, 60% of Belarus’ inhabitants preferred to use Russian in everyday life and 75% favored Belarussian-Russian bilingualism in public life and state institutions.[15]

Statehood

The possession of a national state is the most important fact of the historical proudness of any ethnic group and, moreover, in Anglosaxonic political philosophy, the term „nation“ is directly linked to the state or to say in other words, terms „nation“ and „state“ are, basically, the synonyms. Therefore, only those ethnic groups in the possession of their own state, or at least in the process of striving to create/recreate it, can be called the real nations. The others are only the ethnic groups living as minorities in not their own political organizations. Subsequently, there are stateless ethnic groups[16] and statehood nations. Hereby for many ethnic groups, it is of focal importance to „prove“ that historically they belong to the category of statehood nations rather than to the stateless minorities. The case of Belarussians is one of the most characteristic examples in this matter and it is in direct connection with the problem of Belarussian national identity.

Here it is important to notice that the modern term nation or natio is authentically coming from the Latin word nasci what originally meant „to be born“. From the very cultural point of view, a nation is a group of people who are bonded together by a common language, religion, history, customs, and traditions but politically, a nation is a group of people who regard themselves as a „natural“ members of their own political community – the state, and it is historically expressed by the common desire to establish and maintain political sovereignty or at least autonomy (like, for instance, the Catalans in Spain or the Scots in the UK). Therefore, if the state is composed of its „natural“ members, it is expected by them to express the highest degree of patriotism or, literally, a love of their own fatherland that is, basically, a psychological attachment of loyalty, based on group solidarity, to the national state or the political community by birth.[17] Subsequently, from the very psychological viewpoint, a nation is a group of people who are sharing loyalty to each other in the form of patriotism.[18] However, a group of stateless people can lack national pride as being „inferior“ in comparison to historical (statehood) nations regardless of the fact that they share a common cultural and historical identity usually founded on a belief in a common descent.

For Belarussian nationalists is very difficult to find deeper historical foundations of their national statehood at least before the time of Russian Bolshevik Revolution and Russian Civil War of 1917−1921 when in 1918 the so-called Belarussian People’s Republic was formally proclaimed under German military occupation. At the same time, the First Belarussian Congress was convened but never took place as it was thwarted by the Bolsheviks who finally won the civil war and established a Soviet Republic of Belarussia composed by today’s eastern and central parts of Belarus while its western parts were annexed by reborn Poland according to Bolshevik-Polish Peace Treaty of Riga on March 18th, 1921.[19] Hereby a Soviet Belarussia became a founder republic of the USSR in 1922 and, therefore, it can be treated as the first national state of Belarussians.

We have to keep in mind that Soviet authorities established for each recognized ethnic nation a separate socialist republic as its national state within the federation system of the Soviet Union. In political theory, „the state is a political association that establishes sovereign jurisdiction within defined territorial borders…a state is characterized by four features: a defined territory, a permanent population, an effective government, and sovereignty“.[20] Theoretically, it is quite clear that a state is a synonym for the country that means a formal international recognition of territory’s „independence“ is not necessary for it to be treated as a state. Hereby according to the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, there are three criteria of statehood:

- It possesses a stable government.

- It controls a definite territory.

- It enjoys the acquiescence of the population.[21]

It is obvious that all those three criteria were applicable in the case of Soviet Bellarussia and, therefore, it can be concluded that the Bolshevik-established Soviet Belarussian republic within the USSR was historically the first national state of Belarussians. Nevertheless, all crucial forces in fighting for a Belarus’ statehood were, in fact, of external nature but not internal, which means that a Belarus’ statehood is of the artificial (in essence, a Russophobic) nature.

Mythology

After the Russian Civil War of 1917−1921 the split of Belarussian identity continuous within two camps:

- The pro-Western nationalists, who were gaining support from Belarus’ activists from Poland for the sake to separate Soviet Belarussia from the USSR.

- The pro-Russian orientation citizens, who advocated a Russophile stance, taking into consideration a focal fact that most citizens of Belarus were of Christian-Orthodox cultural background like Russians and, therefore, a Russia’s role as a fundamental cultural donor to Belarus had to be respected.

Nevertheless, in the interwar time from 1921 to 1939, according to the internal passport record of ethnicity, the Belarussians existed only on the Soviet but not on the Polish side.

Belarussian nationalists in the search for an appropriate historical background of Belarussian national statehood went to the area of mythology as the only instrument to be used in order to „prove“ their artificial claims.[22] The case of Belarus’ nationalists is a good example of how the people, or some political groups, are willing to be engaged in a nation-building process but without previous assurance that their national history is a glorious and of a statehood nature. For the reason that Belarus’ history was not adequate at all in regard to Belarussian statehood, it was quite necessary to involve appropriate myths for the sake to „find“ a national state in historical sources. The final purpose was, in fact, to show that Belarus’ state independence after the collapse of the USSR is not a new one but rather a revival of older Belarussian statehood.

In principle, national myths and academic mythology are very useful for the creation of recombinations of the real history, or better to say, for its rewriting according to the political goals and national wishes.[23] It is clear that academic historians, philologists, linguists, ethnologists, or folklorists are playing a crucial role in the process of making and spreading the myths about national identity regardless of the fact that not so much of their work is, in fact, scientifically tested truth.

As a result of Belarussian statehood mythology, it was published in 2001 in Vilnius a book by Orlov and Saganovich under the title: Ten Centuries of Belarusian History (862−1918).[24] The book is just one (but remarkable) example of the writings which direct historiography in a way to be acceptable to the pro-Western orientation of the politics by Belarussian nationalists who are being unable to find any Belarus and Belarussians in the medieval chronicles and other historical sources, understood the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL) not only as of the precursor of the modern state of Belarus but even as the heyday of Belarussian national statehood taking into consideration that at least more than 50% of GDL’s inhabitants have been East Slavs.[25] Even after the 1569 Lublin Union, the Slavs were the majority in GDL, but according to Belarus’ nationalists, they have been exactly Belarussians and, therefore, East Slavonic language both spoken and being in official use by the state authorities in GDL (at least before 1569 when it started to be Polonized) was proclaimed to be „Old Belarussian“.

The question of language, as the language is considered as a prime marker of national identity, is of the crucial importance for Belarus’ nationalists for whom the most important task is to „prove“ in historical sources that Belarussians had and have a separate language from Russian. In reality, traditionally, the Belarussian language (speech/dialect) was a rustic or peasant vernacular which was becoming more Russian or Polish as a person became urbanized and searching for a higher social position as the language was refined by an urban type of life and personal education.[26] The case of pre-WWII Vilnius is, in this matter, very illustrative: one-third of its inhabitants were speaking Jidish, Polish was speaking on the streets, in the schools, and in the churches while Belarussian was speaking in the countryside around the city. In 1939, almost no one was speaking Lithuanian in Vilnius.[27]

For the Belarussian camp of the nationalists, the crucial task was to find a precursor of a modern independent language of Belarus as a proof of a separate Belorussian nationhood. This search for a major person of prominence as a writer who used Belarussian language led them to Frantisek Skaryna (a. 1490−a. 1552), who, however, was known for the long period of time as a translator of religious texts into „the simple Russian language“ – a language which now became appropriated by Belarus’ nationalists as a precursor of modern Belarussian. There are international encyclopedias and other relevant academic publications in which F. Skaryna is clearly labeled as Russian and a translator of the Bible into Russian but not into any kind of Belarussian.[28] The Balarussification of F. Skaryna and his work are an order of the day for Belarussian nationalists as he is, in fact, seen as a father of modern Belarus’ national language and, therefore, at the same time, and of a contemporary Belarussian nation as a separate ethnolinguistic group (especially from Russians).

During the last quarter of a century, Belarus is faced and with the question of national symbols which are reflecting at high degree the national identity and political orientation features. The politics of national symbols (flag & coat of arms) are supported by different mythologies and political orientations – pro-Western and pro-Russian. The first group insists on the use of the symbols more related to GDL while the second camp is supporting the use of the state symbols from the Soviet era officially introduced in 1995 and, therefore, current Belarus’ flag and national emblem are the only ex-Soviet insignias in the official use. As a result, Belarussians are today the only post-Soviet nation that returned to its Soviet emblems for two reasons:

- It confirms historical fact that Soviet Belarus was, in fact, the first and, therefore, authentic national state of Belarussians.

- It shows the wish of the majority of the population that Belarus’ political and national orientations have to be directed toward the East (Eurasian integration) rather than toward the West (NATO/EU integration).

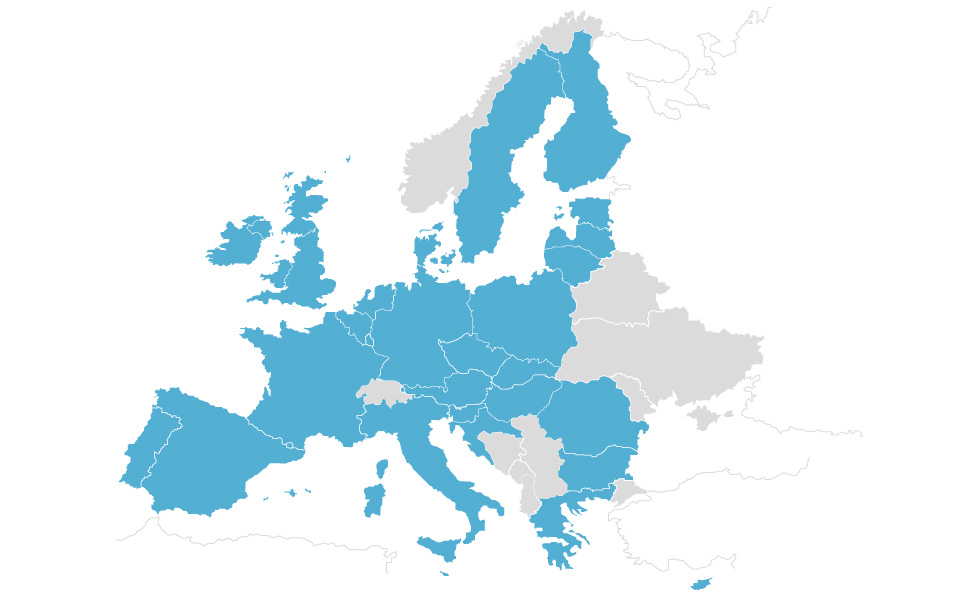

Between West and East

It has to be explained why today majority of Belarus’ citizens have quite positive attitudes toward Russia – a country seen by them as the most reliable partner of Belarus. As a matter of fact, Belarus was after WWII one of the Soviet republics which mostly benefited from its membership of the USSR for the very reason that it was properly industrialized despite its lack of mineral resources (similarly to the Baltic republics). Belarus peacefully gained its internationally recognized independence as a consequence of the August Coup in Moscow on August 26th, 1991 followed by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. As a post-Soviet Russia is a legal successor of the USSR, it is seen by many Belarussians as natural to have as better as relations with the country from which they quite benefited in the recent past taking as well as into consideration very close ethnic, linguistic and cultural ties with Russia and Russians. Among all ex-Soviet republics, therefore, Belarus is mostly attached to Russia which is also seen as a Belarussian protector from Western economic and political policy of brutal liberal-democratic imperialism experienced by all East-Central and South-East European countries after 1991. The Russian language was introduced as equal with Belarussian according to the results of a 1995 plebiscite followed by Belarus’ joining a Union with Russia in 1999 with the aim to create a customs and currency single area, a common parliament, and a common judiciary.[29]

On the other hand, it is quite obvious that Belarussian nationalists are trying to establish a popular legitimacy to their own (pro-Western and anti-Russian) version of Belarus’ national mythology especially within the domain of historiography for at least three fundamental political reasons and national tasks:

- To dissociate Belarus from Russia and Russians.[30]

- To propagate alleged national, historical, political, linguistic, economic, and cultural harms inflicted by Russia on Belarus.

- To create an atmosphere of political Russophobia in Belarus in order to turn the country to the Western direction (NATO/EU).[31]

For the purpose of a pro-Western political orientation of Belarus, it is chosen GDL by many ultranationalists in Belarus as, allegedly, a national state of Belarussians based on three claims:

- GDL was established and governed not by ethnic Lithuanians but rather by ethnic Belarus (i.e., Беларусь)

- The ethnonym Lithuanian(s) is derived from the ethnonym of ancient East Slavs (i.e., Belarus) – Litvinais (Licvinais), who has nothing in common with the Baltic people as they have been Belarus Slavs.[32]

- GDL as a national state of Belarus means that Belarussians are one of the oldest and most powerful European historical nations.

The proponents of anti-Russian and pro-Western course of Belarus’ politics are using well-known Western-sponsored fake-news propaganda cliché to accuse a legitimate Belarussian President of autocratic governing style, suppression of political opposition, restriction of freedom of speech, closing and controlling non-governmental media and even for sponsoring death squads who are murdering the members of political opposition.[33]

Conclusions

As the fundamental conclusions of this research article, the following points have to be emphasized:

- Still today there is no developed a single Belarussian ethnolinguistic identity to be accepted by a majority of Belarus’ citizens.

- The cultural-political leadership of Belarus is sharply divided into two opposite and antagonistic camps: a) Pro-Westerners; and b) Pro-Russians.

- Pro-Westerners are building up Belarus’ ethnogenesis on the foundation of Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a national state of Belorussians and hereby struggling for Belarus’ inclusion into Euro-Atlanticist integration framework.

- Belarus’ pro-Westerners blame all the focal setbacks of their policy on Moscow crafted Russification of Belarus rather than understanding that the majority of citizens wants as much as closer ties with Russia but not with NATO and EU.

- Pro-Russians are seeing Belarus according to the ideological supporters of West-Russism and, therefore, accepting political, economic and cultural pro-Moscow orientation.

- Belarussian nationalistic public workers succeeded to formulate Belarus separate identity as non-being Polish and non-being Russian but totally failed in formulating what historically Belarus’ exceptional ethnonational identity is.

- To be Belarus’ today is much more political-geographic identity expression than ethnolinguistic one.

[1] Jan Palmowski, A Dictionary of Contemporary World History from 1900 to the Present Day, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 56.

[2] In this article, I use an adjective Belarussian but not Belarusian as the second option is, in fact, an artificial politicized Russophobic construction. In German historiography, for instance, is used only the first option (Weißrussische) [Prof. Dr. Hans-Erich Stier at al. (eds.), Westermann Großer zur Weltgeschichte, Braunschweig: Westermann Schulbuchverlag GmbH, 1985, 160].

[3] Grigory Ioffe, “Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity”, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 55, No. 8, 2003, 1241.

[4] A President of Belarus, Alyaksandr Lukashenka is calling himself as an “Orthodox atheist”, i.e., the atheist with a Christian Orthodox background.

[5] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Revised edition, London: Verso, 2016.

[6] Max Weber, “What is an Ethnic Group”, Montserrat Guibernau, John Rex (eds.), The Ethnicity. Reader. Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Migration, Maiden, MA: Polity Press, 1999, 18.

[7] Lithuanian historiography is for parts of Belarus and Ukraine annexed by Grand Duchy of Lithuania using the term Gudija which was populated by East Slavs (gudai) who are at such a way separated from Russians (i.e., by today’s Belarussians and Ukrainians) [Arūnas Latišenka et al., Didysis istorijos atlasas mokyklai nuo pasaulio ir Lietuvos priešistorės iki naujausiųjų laikų, Vilnius: Briedis, without a year of publishing, 84]. Lithuanian historian Zigmas Zinkevičius declaratively claims that the ethnonym Baltarusija (in Lithuanian) (Belarussia in English) is a product of Russian propaganda [Zigmas Zinkevičius, Lietuviai: Praeities, Didybė ir Sunykimas, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2013, 125]. The ethnonym Ruthenians “is the name given to those Orthodox East Slavs who were ruled by non-Orthodox sovereigns. Since its speakers were Orthodox Christians, the Ruthenian language was influenced by Church Slavonic. It was spoken in the territory of contemporary Belarus and Ukraine and is the precursor of the modern Belorussian and Ukrainian languages, as well as modern Rusyn” [Barbara Törnquist-Plewa, „Contrasting Ethnic Nationalisms: Eastern Central Europe“, Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 193]. The ethnonym Ruthenians is derived from the Latin term Rutheni and it is historically and today very politically applied in order to separate them from the same ethnolinguistic group of East Slavs within Russia called Moscovitae (i.e., those under the administration of Moscow). Ruthenians are, for example, called in Lithuanian historiography as Rusėnai – East Slavs living in Lithuania, Poland and Hungary [Alfredas Bumblauskas, Senosios Lietuvos istorija 1009−1795, Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 2007, 218]. Hereby Western historiography is not living space for the Russians as an ethnolinguistic group in the Middle Ages as East Slavs were composed only by Ruthenians or Moscovitae. “However, the Ruthenians called themselves ruskije in their own language, the same name as the Moscovitae also gave to themselves. Both groups inherited this name from the period when they were united within Kievan Rus between 800−1240” [Barbara Törnquist-Plewa, „Contrasting Ethnic Nationalisms: Eastern Central Europe“, Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 193]. As a matter of fact, Kievan Rus’ was the first-ever established state to politically organize East Slavs, with Kiev as its capital. Today there are three modern nations who trace or pretend to trace, their ethnolinguistic origins back to Kievan Rus’: Russians, Belarussians, and Ukrainians. Nevertheless, the original name of the state is in modern history best preserved in the form of Russian ethnonym that is telling a lot about which contemporary nation has the most historical, ethnic, linguistic, cultural and moral rights to Kievan Rus’ heritage. For instance, the most important law code (codex) of Kievan Rus’ is named Russkaya Pravda (1016) but not Ukrainian or Belarus pravda. This codex later became the foundation of the law system in Russia [Jevgenij Anisimov, Rusijos istorija nuo Riuriko iki Putino: Žmonės. Įvykiai. Datos, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2014, 40]. The ethnonym Ruthenia survived in contemporary history only for the tiny territory in post-WWI Czechoslovakia (in fact in Slovakia) but in 1945 Subcarpathian Ruthenia was separated from Czechoslovakia and annexed by Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine, where it became renamed into Transcarpathian Oblast [Chris Hann, „Nation and Nationalism in Central and Eastern Europe“, Gerard Delanty, Krishan Kumar (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Nations and Nationalism, London−Thousand Oaks−New Delhi: SAGE Publications, 2006, 401] with a full degree of Ukrainization of the ethnic Ruthenians (i.e., the Russians). It is worth to mention that for some Ukrainian historians, the epoch of GDL’s occupation of the biggest part of today’s Ukraine (1320−1569) is “the darkest time of Ukrainian history” [Andrijus Blanuca et al., Ukraina: Lietuvos epocha, 1320−1569, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2010, 10].

[8] On the creation of a Belarussian nation, see [Nickolas Vakar, Belorussia: The Making of a Nation, Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press, 1956.]. Similarly to the Soviet case, Yugoslav communist authorities created after 1945 three new nations: Montenegrins, Macedonians, and Muslims (today’s Bosniaks).

[9] It is a common Western propaganda pattern that “it is really only the former Soviet republic of Belarus that remains outside the democratic family” [David Gowland et al., The European Mosaic: Contemporary Politics, Economics and Culture, Third Edition, Harlow, England: Prentice Hall, 2006, 421].

[10] M. Donald Hancock et al., Politics in Europe: An Introduction to the Politics of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Russia, and the European Union, Third Edition, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, 462.

[11] Belarussian pro-Western political opposition welcomed Minsk-Brussels signature on the EU’s Partnership and Cooperation Agreements in 1995. However, this agreement “did not come into force because of the deteriorating situation” [David Gowland et al., The European Mosaic: Contemporary Politics, Economics and Culture, Third Edition, Harlow, England: Prentice Hall, 2006, 514]. After the dissolution of the USSR, however, Belarus became “Russia’s closest partner” and, therefore, these two countries signed in 1995 a treaty of friendship and cooperation, in 1996 established a “deeply integrated Community” and in 1997 Community was converted into a Union which would, according to the project, involve a common legislative space and a single citizenship [M. Donald Hancock et al., Politics in Europe: An Introduction to the Politics of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Russia, and the European Union, Third Edition, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, 452−453].

[12] According to Belgrade University-based Professor Predrag Piper, Russian language is today spoken by 159 million, Ukrainian by 42,5 million and Belorussian by 9,3 million speakers [Предраг Пипер, Увод у славистику, Књига 1, Београд: Завод за уџбенике и наставна средства, 1998, 25].

[13] The same “alphabetic schizophrenia” is already applied in the practice in Montenegro after its proclamation of independence in 2006. Hereby the Latin alphabet is, in fact, in use by all state authorities rather than traditional and national Cyrillic which is the same as Serbian Cyrillic. About the language as a principal national flag in ex-Yugoslavia, see [Victor A. Friedman, Linguistic Emblems and Emblematic Languages: On Language as Flag in the Balkans, Columbus, USA: The Ohio State University, 1999].

[14] Предраг Пипер, Увод у славистику, Књига 1, Београд: Завод за уџбенике и наставна средства, 1998, 144.

[15] Burant S. R., “Foreign Policy and National Identity: A Comparison of Ukraine and Belarus”, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 47, No. 7, 1995, 1125−1144.

[16] Today, the Kurds are probably the largest stateless ethnolinguistic group in the world (up to 30 million). On “stateless nations”, see: [Julius W. Friend, Stateless Nations: Western European Regional Nationalisms and the Old Nations, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Mikael Bodlore-Penlaez, Atlas of Stateless Nations in Europe: Minority Peoples in Search of Recognition, Y Lolfa, 2012; James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups Around the World, I−IV Vols., Second edition, Westport, Connecticut−London: Greenwood, 2016]. On the Kurdish Question, see [Merhard R. Izadi, The Kurds: A Concise Handbook, New York: Taylor & Francis, 1992; Gerard Chaliand, A People Without Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan, Interlink Publishing Group, 1993; Kevin McKiernan, The Kurds: A People in Search of Their Homeland, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2006; Susan Meiselas, Kurdistan in the Shadow of History, Second edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008; Michael M. Gunter, The Kurds: A Modern History, Princeton, New Jersey: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2016].

[17] The word “patriotism” is derived from the Latin “patria” (a land of the father).

[18] On patriotism, see [Igor Primoratz (ed.), Patriotism, New York: Humanity Books, 2002; Charles Jones, Richard Vernon, Patriotism: Key Concepts in Political Theory, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018].

[19] The Peace of Riga in 1921 is a consequence of the Bolshevik-Polish War of 1919−1921 which started Piłsudski-led Poland in order to annex eastern territories of the pre-1772 Poland not included into the post-WWI Republic of Poland according to the project of Curzon Line. The treaty was signed after the decisive victory by Józef K. Piłsudski in front of Warsaw in 1920 (“Miracle of the Vistula”) [Jan Palmowski, A Dictionary of Contemporary World History from 1900 to the Present Day, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 557].

[20] Andrew Heywood, Global Politics, Printed in China: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 114.

[21] Ibid., 341.

[22] Similarly to the Belarussian nationalists, their Croatian colleagues, for instance, did the same in searching for long-standing Croatian statehood, which according to their writings, existed after 1102 when, in fact, Croatia with Slavonia became on the volunteer basis expressed by Croatian nobility an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary. As a classic example of the rewriting Croatian history in this matter, one can offer the next “academic” publications [Ivo Perić, Povijest Hrvata, Zagreb: Centar za transfer tehnologije, 1997; Dragutin Pavličević, Povijest Hrvatske. Drugo, izmijenjeno i znatno prošireno izdanje sa 16 povijesnih karata u boji, Zagreb: Naklada P.I.P. Pavičić, 2000]. Compare with a much more academic-scientific approach in [László Kontler, Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary, Budapest: Atlantisz Publishing House, 1999].

[23] As a good example, how history textbooks are rewritten in an ethnocentric way, see [Christina Koulouri (ed.), Clio in the Balkans: The Politics of History Education, Thessaloniki: Center for Democracy and Reconciliation in Southeast Europe, 2002].

[24] The book is originally published in Belarussian language and consists 200 pages. Similarly to this Belarus’ case, the contemporary Croatian historiography claims about “thousand years of Croatian statehood”.

[25] Lithuanian academic historiography claims that, for instance, „in the mid-16th century Lithuanians constituted about one-third or more of GDL, whose total population may have reached 3 million people…More than half of the population were Slavs, who at various times had lived in the Eastern and South-Eastern lands annexed by GDL“ [Zigmantas Kiaupa et al., The History of Lithuania before 1795, Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2000, 162]. However, according to Lithuanian history textbooks, in 1430 there were 72% of East Slavs and in 1569 there were 63% of them out of total GDL’s population [Ignas Kapleris, Antanas Maištas, Istorijos egzamino gidas: Nauja programa nuo A iki Ž, Vilnius: Briedis, 2013, 123]. A GDL’s capital Vilnius (est. 1323) was settled by a community of Russian Orthodox believers even before Lithuania introduced (Roman Catholic) Christianity in 1387 [Stasys Samalavičius, An Outline of Lithuanian History, Vilnius: Diemedis leidykla, 1995, 101].

[26] Grigory Ioffe, “Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity”, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 55, No. 8, 2003, 1246.

[27] Timothy Snyder, Tautų rekonstrukcija: Lietuva, Lenkija, Ukraina, Baltarusija 1569−1999, Vilnius: Mintis, 2008, 17.

[28] According to Snyder, F. Skoryna was an East Slavic Renaissance actor [Ibid., 24].

[29] Jan Palmowski, A Dictionary of Contemporary World History from 1900 to the Present Day, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 56.

[30] For the same reason, Lithuanian historiography and political sciences are not considering, in fact, ethnic Russians to exist on the territory of historical GDL calling its East Slavic inhabitants as gudai – a term used by GDL’s authorities and administration for its East Slavs. However, a leading contemporary Lithuanian historian, Edvardas Gudavičius, recognizes that gudai are nothing else but, in fact, the Russians: “Rusus lietuviai vadino gudais” (in English: Lithuanians were calling Russians as Gudai) [Edvardas Gudavičius, Lietuvos istorija I tomas: Nuo seniausių laikų iki 1569 metų, Vilnius: Akademinio skautų sąjūdžio Vydūno fondas Čikagoje−Lietuvos Rašytojų Sąjungos leidykla, 1999, 436].

[31] Similarly to Belarus’ case of orchestrated Russophobia, in Soviet Lithuania “both the Poles and the Lithuanians unfavorably judged the Russians (or more precisely Russian-speakers) who arrived from the other Soviet republics as undesirable competitors who worsened the social position of the local inhabitants. (The incomers had priority in obtaining work, living space, etc.)” [Vitalija Stravinskienė, “Between Accommodation and Resistance: Interethnic Relations in East and Southeast Lithuania (1944−1953)”, Vida Savoniakaitė (ed.), Contemporary Approaches to the Self and the Other, Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2014, 180].

[32] Zigmas Zinkevičius, Lietuviai: Praeities, Didybė ir Sunykimas, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2013, 125.

[33] The same cliché was used by the West in the cases of Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi or Slobodan Milošević.

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS