Views: 1157

A historical overview and Estonia’s minorities

Estonia (Eesti, Estland) is a Baltic state that was colonized by the German Teutonic Order of Knights from 1346 being, therefore, dominated politically and economically by a German-speaking landowning aristocracy, which succeeded to maintain its social and economic position even during the Swidish occupation of the territory of present-day Estonia from 1561 to 1721 and for most period of subsequent Russia’s administration since 1721 to 1915. From 1855 the ethnic Estonians received the right to possess the land. Migration increased the Estonian population in the cities during the time of the Russian administration. It is something that from the 1880s an Estonian nationalism became developed which was accelerated after the Japanese-Russian War in 1904−1905 followed by the Russian Revolution of 1905. Several important national symbols of Estonia date from the late 19th century as, for instance, the blue-black-white tricolor, introduced as the banner of the Estonian students’ society in 1884. As a matter of curiosity, the original 1884-flag miraculously survived the turmoil of the 20th century. It is important to emphasize that after 1914, the Estonian independence movement became crucially dominated by anti-Russian Bolsheviks. During the German occupation in 1915−1917, a nationalist puppet Estonian government was established. For Estonians of whom about 100.000 fought in the WWI and about 10.000 fell, the final impetus towards a formal independence was the Bolsheviks’ establishment of a dictatorship in late 1917. Estonia has never been independent until 1918. Seizing the opportunity offered by the withdrawal of the Bolshevik red militia ahead of the advancing German troops, the National Salvation Committee of the Estonian Diet (Parliament) proclaimed Estonian state’s independence on February 24th, 1918 (Lithuania did the same a week before on February 16th). After Germany’s collapse in November 1918, Estonia had to defend its independence against both the Red Army and the Landwehr, a militia formed by the Baltic German nationalists. However, an essential military aid was provided by the UK’s fleet, which arrived in Tallinn at the most crucial moment of the war, the end of December 1918. Finally, the Estonian government successfully fought the Bolsheviks, with a great foreign help especially from Finland,[1] the UK, and Denmark and as a consequence, Estonia signed the Tartu Peace Treaty on February 2nd, 1920 with the Lenin’s government in Moscow.[2]

The proclamation of the Republic of Estonia was in 1920 followed with immense land reform which expropriated the wealthy landowners, mostly German,[3] and, therefore, the state’s authorities received a critical support of the mass of the common people who received small portions of land. At that time, the Estonian society was relatively homogeneous with 88% of ethnic Estonians followed by mainly Russian-speakers as the most numerous ethnic minority. Such ethnic breakdown led the country in the interwar period to an atmosphere of interethnic toleration for the very reason that the ethnic Estonians could afford to appreciate the cultural and linguistic distinctiveness of Russians, Germans, Swedish, and Jews as minorities.[4] Estonian authorities allowed every minority group which was composed of more than 3.000 members to constitute itself into a corporate body. Such minority had a right to elect their own cultural delegation to deal with minority’s schools, clubs, and other organizations of their own. However, Estonia, like many other countries, suffered serious economic and social dislocations at the time of the Great Economic Depression in 1929−1933 what had a negative impact to its political life as the popularity of the Fascist movement and ideology increased. In order to prevent the Fascists to take power in the country, the President Konstantin Päts, dissolved Parliament and declared martial law in 1934 which, in principle, did not have big negative consequences for Estonia’s minority as their rights left mainly unchanged.[5]

As a consequence of the terms of a secret protocol of the Hitler-Stalin Pact (August 23rd, 1939), Estonia became incorporated into the USSR on August 6th, 1940 while in June 1941 was occupied by Nazi Germany till 1944 when became reintegrated into the Soviet Union once again.[6] In the 1950s, the ethnic Estonian population in Estonia was reduced to some 60% in comparison to the pre-war time due to the war and forced deportations organized by both Germans and Soviets. After the war, there was a big influx of the working power from other Soviet republics to the Baltic states particularly to Estonia and Latvia.[7] A Soviet Estonia was the wealthiest of all three Baltic republics whose each of them separately had been among the leading Soviet republics taking into consideration an average income per capita. The political and economic reforms (Perestroika and Glasnost) introduced by M. Gorbachev („Terminator of the Soviet Union“) in the late 1980s resulted with the declarations of independence by the three Baltic States.[8] A second Estonian state’s independence was declared on March 30th, 1990, and recognized by Moscow (Boris Yeltsin) on August 28th, 1991.

However, Estonian (and Latvian) minority’s policy after 1991 had nothing in common with the prie-WWII one as the government’s policy against minorities, i.e., the Russians, was harsh, anti-democratic and even racist at least until 1995 when the government accepted a suggestion by the EU to improve to certain degree the position of the minorities as one of the crucial conditions for Estonia’s accession (in 2004). Now, all residents who had lived in Estonia for a minimum of five years, followed by some other conditions, could become citizens if they want.[9] After Estonia’s accession to the EU, the citizenship conditions became from some points of view accommodated to the general EU’s requirements and standards but, however, both Estonia and Latvia, in principle, prefer more nationalistic the Jus sanguinis (right of blood) instead of more democratic Jus soli (right of soil) principle dealing with the question of the citizenship rights.

Citizenship

Here we have to keep in mind that the citizenship is a juridical status granting a sum of rights and duties to members of a specific political entity/community.[10] The citizenship policy is today understood as a pillar of a modern state that is of an extreme importance in the process of integration or disintegration of the minorities. The notion of citizenship is, however, unlike that of subjection as the subjection implies a personalized relation of obedience and submission of subjects to the sovereign. Nonetheless, the notion of citizenship involves a relation of reciprocial loyalty between an impersonal institution (state) and its members (not subjects). A subjection belongs to the traditional (feudal) and charismatic political systems and social relations. In other words, the notion of citizenship fits to „institutionalized state“ while the notion of subjection fits to „personalized state“. Citizenship, in essence, is giving to someone the political rights concerning the exercise and control of political power, to vote and create political parties. That was, basically, the main reason for the post-Soviet policy of discrimination on ethnic bases in Estonia and Latvia concerning the question of citizenship as both Tallinn and Ryga wanted to deprive their considerable Russian-speaking minorities from political rights as they have been being understood as „politically dangerous“. Estonia and Latvia, in fact, literally understood and brutally applied the principle of „staatsnation“ („ein sprache, ein nation, ein staat“), a German term of the French origin, after 1991: each nation (ethnocultural-linguistic group) must have its own state with its own territory and each state must comprise only one nation (no place for minorities, i.e., for the others at least from the political point of view). According to common sense and most theoretical representations, a „staatsnation“ is, in fact, „kulturnation“ – community whose members share the same cultural origin and features. The problem is that the principle of „staatsnation“ requires the formation of politically sovereign monocultural and monoethnic territorial spaces of the political entity (state). Furthermore, the idea of „staatsnation“ is founded on cultural and ethnic purity and, therefore, the others have to be either assimilated (if it is possible) or cleansed (if the first option will not work properly) in order to make the national state as much as ethnically and culturally homogeneous. In practice, the politics of ethnocultural recomposition in the name of the brutal realization of the principle of „staatsnation“ is resulting in boundary revisions, forced assimilations, banishments, planned immigrations or forced deportations. The political association based on the principle of „staatsnation“ is offering limited opening towards the others or the foreigners as not everyone can indiscriminately belong to a specific national state. Surely, national state is an association partially open towards the outside. Such view, like in Estonia and Latvia, is calling for the creation of institutional mechanisms of social selection that regulate affiliation and exclusion like the institution of citizenship which together with the notion of nationality represent the fundamental tools for the national state to define who has the complete right to belong to such state (ethnic Estonians or Latvians) and who is excluded from it (a Russian-speaking minority).[11]

A Russian-speaking minority in independent Estonia

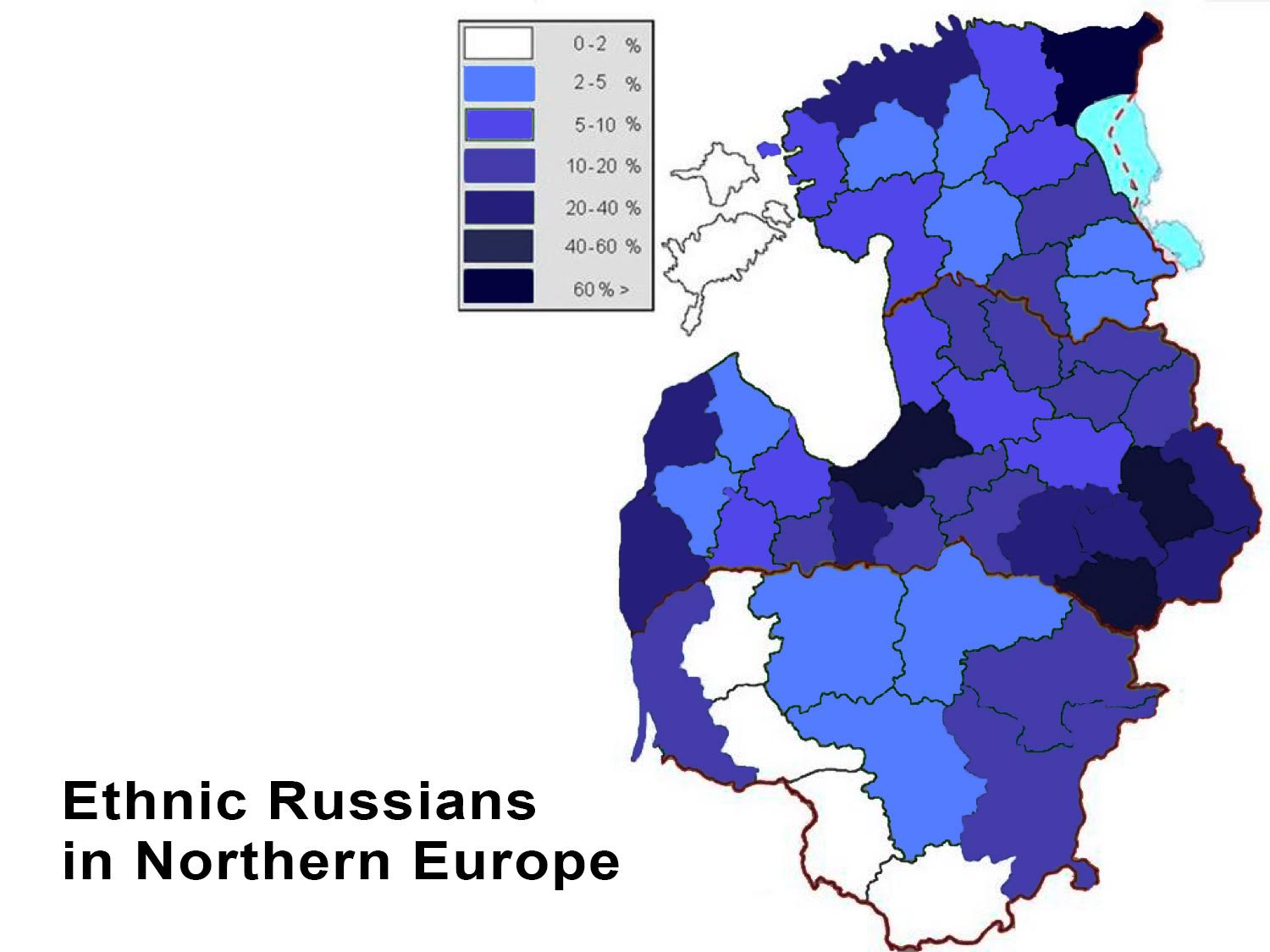

Estonia with a population of 1.3 million with 400.000 of them living in capital city Tallinn has one of the lowest population density in the world (30 per sq. km.). According to the last official census (2011), the ethnic Estonians made 69.7% of the total population followed by Russians (25.2%), Ukrainians (1.7%), Belarussians/Belarusians (1.0%) and Finns (0.6%).[12] As it is obvious, from the time of second independence (1991) up today the Estonian government has to deal primarily with the Russian ethnic minority concerning to find modus vivendi of the Estonian political prosperity. In other words, further political stability of Estonia primarily depended and depends on the issue how the Russian-speakers of Estonia are going to be integrated into or disintegrated from the Estonian political and social system established after the dissolution of the USSR.

The Russian minority in Estonia resides primarily in three areas of the country: the capital city Tallinn (38%), the border city of Narva (86%), and Kohtla-Jarve (69%). Although the group is distinct in terms of culture, language, and religion, the issue of the Russian minority in Estonia, as potentially problematic one, is a new one, dating back to the early 1990s when Estonia declared its sovereignty becoming independent for the second time in history but at the same time introducing a racist citizenship policy and, in general, discriminatory policy toward minorities targeting primarily the Russian-speakers.[13] As a fundamental explanation for such anti-Russian attitude by the Estonian authorities, one can hear that this is an Estonian retaliation for the Soviet policy of Russification of Estonia after the WWII as the major influx of ethnic Russians into Estonia took place under the Soviet policy of population intermixing. The ethnic composition of Estonia (previously small and homogeneous population), therefore, was drastically altered as the Russians were the group that immigrated in the greatest numbers to Estonia. Nevertheless, the Western “liberal democracies” (including the EU too) did not so much to criticize or halt such Estonian “retaliation” to the USSR – the country which did not exist after 1991 and the country which recognized Estonia’s independence before January 1st, 1992 when the Soviet Union itself ceased to exist. Estonia (as Latvia as well) became a member state of both the EU and the NATO without essentially changing its minority (anti-Russian) policy of discrimination and Estonization of which the glorification of Estonia’s (as Latvia’s in Latvia) Nazi past during the WWII is a part of it.[14]

Nevertheless, despite their migration to Estonia, either the Russian population did not assimilate into the local society during the Soviet time or ethnic Estonians became Russified. The situation for the Russian minority in Estonia, however, changed dramatically after the declaration of Estonia’s independence in 1991 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. With the adoption of the new Estonian constitution, many Russians who were born and lived their entire lives in Estonia had overnight become inhabitants without a citizenship and political rights (to vote and to have their own party’s representatives at the parliament). Here is worth to mention that a linguistic policy of a new independent Estonia (like in Latvia and Lithuania too) is quite different in comparison to the Soviet one: while in the Soviet time there were two languages in practical use in Estonia (Estonian and Russian), in a new Estonia it is the only one official language in the public use – Estonian.

The minority speaking population’s current disadvantages are directly linked to the legislation adopted by the Estonian government after 1991. Specifically, the widely criticized by the NGO’s the Estonian citizenship law requires evidence of either the pre-World War II historical roots in Estonia or the belonging to the Estonian ethnolinguistic nationality (Jus sanguinis-right of blood) to be considered a citizen of Estonia. Those that do not fulfill this requirement must pass a language exam[15] and demonstrate sufficient knowledge of the Estonian history.[16] The language restrictions also adversely affect minority’s educational and occupational opportunities. While the Russians are permitted to participate in the local elections, there are still significant legal restrictions in terms of voting and organizing at the national level and attainment of high political office for non-citizens. Once they achieve a citizenship, however, there are no restrictions. In addition, there are limited restrictions in recruiting Russian military and police and attaining access to civil service. Although the citizenship law has been amended due to an extensive pressure by Russia and various European institutions, the problem has not been solved to both the full satisfaction of the Russian minority and the international standards on the protection of minority rights.[17] This is true because two reasons: double citizenship is not allowed in Estonia, and Estonia’s born non-Estonian ethnolinguistic inhabitants are not getting automatically citizenship (Jus soli-right of soil).

Consequently, elimination of Estonia’s post-Soviet citizenship policy and language requirements has been at the core of the Russian minority’s demands since the early 1990s. These grievances have been articulated by a number of conventional political parties, including the Estonian United People’s Party, the Assembly of Russian speakers, the Russian Community, the Russian Party of Estonia, and the Russian Unity Party, among others. So far, the primary forms of group resistance have been a conventional protest and political rallies.

The Russians in Estonia have also received outside moral and humanitarian assistance from the Russian Federation. Various international non-governmental and intergovernmental organizations, including the UNO, the OSCE, the EU, the CE, etc., have also repeatedly expressed their official public concern regarding the treatment of the Russian minority but in practice did not press crucially Tallinn to change it. As a consequence, there were some chances to be open the first Russian language university in Estonia in the capital – “Karolina”, sponsored by a private foundation from Russia. This new university had to be the third one in the whole country according to the number of students after Tartu University (established in 1632 by the Swedish king Gustav II Adolf) and University of Tallinn (established in 2005 as a result of merger of several universities in Tallinn, research institutes and Estonian Academic Library). Today, there are only 13% of the Russian-speakers out of a total number of those who are attending the Estonian universities.

Integration is considered as a process of the formation of a cooperating, democratic and well-functioning society. However, as Estonia re-established the principle of a nation-state in a very brutal form it is a very question how the minorities (especially Russian) can be integrated into the Estonian political system and society. The higher status of the Estonian language is one of the main guarantees for the Estonians for the maintenance of their own ethnic identity in Estonia’s nation-state[18] but on other hands it is not very positively affecting the real integration of Estonia’s minorities (especially the Russian-speakers) into the society and politics.[19] The second guaranty is the political loyalty and acceptance of Estonia’s territorial integrity by the Russian-speaking population. According to the Estonian government’s newest data, there is a tendency of strengthening the state-loyalty of the Russians towards the Republic of Estonia and the increasing respect of Russians towards Estonian culture and language but on other hands it is really hard to believe that the overwhelming majority of the Russian-speakers supports the official idea of Estonia as a “kulturnation” nation-state of the ethnic Estonians in which they are racially discriminated. Therefore, the separatist ideas among the Russian people in Estonia are seen as the only way out from such situation.

However, the conception of development and integration will be successful if it is elaborated and directed by the state. Promotion of the concrete plan is possible if all society could understand the necessity of special efforts to accelerate the integration. Exactly for that purpose in autumn/winter 1997/1998, the Estonian government started developing a strategy for tackling the issue of integration. Thus, on February 10th, 1998 the Estonian government adopted the policy paper under the title The Integration of Non-Estonians Into Estonian Society. The Bases of Estonia’s National Policy. The real results of the integration policy directed by the Estonian government, however, are to be visible only in the far future as the government itself intentionally did some very provocative political moves as it was, for instance, the removal of the “Bronze Soldier” from the center of Tallinn in April 2007 – the event which tremendously deteriorated interethnic relations between the Estonians and the Russians.

Conclusion

At the level of the Estonian government, great efforts were made in order to integrate the Russians into the Estonian society through the adopted government’s programme, accelerated research, as well as extended teaching of the Estonian language to the Russians and other minorities. The basis for the growth of the civic society structures are generally good, but the process of a civic development can have an effect to the integration only when the language separation is diminished and the collective identities of people spring up despite their mother tongue. From this point of view, the crucial problem is still that for the Estonians, the Republic of Estonia is primary the nation-state (political and lingual community), while for the biggest number of ethnic Russians residing in Estonia it is a country of their current domicile without clear political identity primarily due to the racist Estonian policy of citizenship. Adaptation by the Russians and their subsequent integration into Estonia’s life will be a long-term process of adapting to the culture and language of Estonia, while the integration into civil society is going to happen much quicker. The foreign experts are stressing that openness of the Estonian society, good communication, and broader co-operation may contribute to the mutual trust between ethnic Estonians and Estonia’s minorities. Finally, it is obvious that the more one is integrated into the society socially and culturally, the more likely a person is to generate real loyalty to Estonia as “his/her own” society. However, taking into account the present Estonian minority policy, it is much predictable that Estonia’s Russian-speakers will much more tend towards a separation but not towards the integration.

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

sotirovic1967@gmail.com

© Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović 2018

[1] The Estonians, Hungarians, and Finns are belonging to the same linguistic group of the Ugro-Finns.

[2] Estonian History in Pictures, Tallinn: The Estonian Institute (without a year of publishing and enumeration of the pages).

[3] Dr Alan Isaacs et al (eds.), A Dictionary of World History, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, 203.

[4] Jan Palmowski, A Dictionary of Contemporary World History from 1900 to the Present Day, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 202.

[5] The list of authoritarian regimes established in Europe in the interwar period of time is presented in Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, London−New York: Routledge, 1999, 502.

[6] On the issue of communism comes to East-Central Europe, see in Andrew C. Janos, East Central Europe in the Modern World: The Politics of the Borderlands from Pre- To Postcommunism, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000, 229−232.

[7] Jeroen Bult, “Everyday Tensions Surrounded by Ghosts from the Past: Baltic-Russian Relations since 1991” in Heli Tiirmaa-Klaar, Tiago Marques (eds.), Global and Regional Security Challenges: A Baltic Outlook, Tallinn: Tallinn University, 2006, 131.

[8] Paul Robert Magocsi, Historical Atlas of Central Europe, Revised and Expanded Edition, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002, 221.

[9] On the history of Estonia and the Estonians, see more in Toivo U. Raun, Estonia and the Estonians, Updated Second Edition, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2001; Neil Taylor, Estonia: A Modern History, London: Hurst, 2018.

[10] On political communities, see in Max Weber, Economy and Society. An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich, Vol. II, Berkeley−Los Angeles−London: University of California Press, 1978, 901−940.

[11] On citizenship, see in Will Kymlicka, Multicultural Citizenship, Oxford−New York, Clarendon Press, 1996; Herman R. van Gunstern, A Theory of Citizenship: Organizing Plurality in Contemporary Democracies, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1998; Richard Bellamy, Citizenship: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Estonia.

[13] About the issue of the process of democratization after 1991 in Central and East Europe, see in John S. Dryzek, Leslie Templeman Holmes, Post-Communist Democratization: Political Discourses across Thirteen Countries, Cambridge, UK−New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[14] On this issue, see, for instance, in Rolf Michaelis, Estonians in the Waffen-SS, Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 2009.

[15] As a matter of fact, the Estonian language, together with the Hungarian and the Finnish, is the most difficult European language for learning.

[16] It means, in practice, to formally accept the official interpretation of the historical Estonian-Russian relations, for instance, that Russia annexed Estonia but not part of Sweden in 1721.

[17] On minority rights from the perspective of international law, see in Will Kymlicka (ed.), The Rights of Minority Cultures, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

[18] On the issue of language as prime marker of ethnic and national identity in North Europe, see in Lars S. Vikør, “Northern Europe: Languages as Prime Markers of Ethnic and National Identity”, Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 105−129.

[19] About this issue, see in David D. Laitin, “Three Models of Integration and the Estonian-Russian Reality”, Journal of Baltic Studies, 34 (2), 2003, 197−222; Dovile Budryte, Timing Nationalism? Political Community Building in the Post-Soviet Baltic States, London−New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2005.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS