Views: 1773

A Greater Croatia according to the advocates of Illyrian Movement’s ideology

The Illyrian Movement until the creation of political parties (1841)

Certainly, publishing of Lj. Gaj’s Kratka osnova horvatsko-slavenskoga pravopisanja/Die Kleine Kroatische-Slavischen Orthographie in 1830 marked the beginning of the Croatian national revival movement and made Ljudevit Gaj to be a leading figure of it. The essential political-national value of the book was that Gaj proposed the creation of one literal language for all Croats. It was a revolutionary act at that time, which was done, according to Gaj and other leaders of the movement, for the ultimate political-national purpose to unify all Croatian population and Croatian lands. In such a way, the Croats and their lands would be united on the language-literal basis that was a crucial precondition for the Croatian political unification in the coming future.[1]

Lj. Gaj and his followers required that the Croatian national language has to be accepted as an official-bureaucratic medium of correspondence in the Triune Kingdom (Dalmatia-Croatia-Slavonia) within the Habsburg Monarchy instead of the Hungarian, Latin or German. At that time the official language in Croatia-Slavonia (under the Hungarian administration) was the Latin language. However, at the same time, the Hungarian magnates required that exactly the Hungarian language has to be the only official language in all Croatia-Slavonia, but not the Croatian one as the “Illyrians” wanted.[2] Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski was the first Croatian politician who openly required (on May 2nd, 1843) that the Croatian language has to become an official in the Croatian-Slavonian feudal assembly (the Sabor) in Zagreb. Nevertheless, the Hungarian authorities rejected this requirement and at the same time prohibited the use of the Latin language by the Croatian representatives in the Hungarian feudal parliament (the Dieta), requiring the use of only the Hungarian language. The Hungarian Dieta in the same year even decided that in ten years the only Hungarian language is going to be the official language within the whole territory of the “Lands of the Crown of St. István” (i.e. historical Hungary from the Carpathian Mountains to the Adriatic Sea) including and Croatia and Slavonia (these two provinces were parts of Hungary, while Dalmatia has been a part of Austria). This struggle over the language issue in Croatia-Slavonia became the initial bit of fire in Croatia’s society which very soon became politically bipolarized into two opposite political parties: narodnjaci (supporters of the Croatian national revival movement and Croatia’s independence in relation to Hungary) and mađaroni (pro-Hungarians who required much closer links between Croatia and Hungary, i.e. Croatia’s incorporation into Hungary).

A year of 1832 was one of the most important in the whole history of the Croatian national revival movement. Among other things, in this year Ljudevit Gaj asked the Habsburg authorities for the permission to print Croatian national newspaper (hrvatske novine) and wrote in the same year a song “Horvatov sloga zjedinjenje”, which in the following years became in fact a Croatian anthem. This anthem became popular under the title that was derived from the very beginning of it: “Još Horvatska ni propala, dok mi živimo.” In the same year, as well, the Croatian assembly (the Sabor) elected Franjo Vlašić for the post of the Governor (the Ban) of Croatia-Slavonia for the period from 1832 to 1840. He chose General Juraj Rukavina Vidovgradski (1777−1849) as the Vice-Captain of Croatia-Slavonia (according to the Croatian historiography – the Kingdom). On this occasion Rukavina gave a speech in the Sabor, but unusually not in the Latin but rather in Croatian-kajkavian language. Here is of the crucial importance the very fact that a complete Croatian historiography agree that it was in fact the first speech in the national-Croat language in the Croatian-Slavonian Sabor. However, the speech was in the kajkavian dialect (in fact the language) which Croats shared with the neighbouring Slovenes (Kranjci) but not in štokavian dialect – a language understood by the most prominent and leading international Slavic philologists at that time exclusively as the Serbian national language.[3]

As it is mentioned above, in 1832 Ivan Derkos printed one of the most influential books of both the movement and Croat nationalism – Genij domovine nad svojim sinovima koji spavaju (Genius patriae…), which was the first cultural and national(istic) program of the Illyrian Movement with the final idea to create a single literal language of the Croats, whose literature up to that time was mainly written in čakavian and kajkavian dialects (or languages). Josip Kundek promoted the same idea in his work Rec jezika narodnoga in 1832 where he emphasised the old national glory of the Croats[4] regardless on the fact that such claim is not very based on historical facts.[5] However, a mature-developed political program of the movement was framed by the work of count Janko Drašković in the same year of 1832 when he published Disertatia iliti razgovor, darovan gospodi poklisarom zakonskim i buducem zakonotvorcem kraljevinah nasih… However, this manuscript was written in the štokavian dialect, regardless on the fact that Drašković was native kajkavian speaker (likewise Ljudevit Gaj too). The work was even printed in the city of Karlovac where kajkavian dialect was spoken, but not štokavian one. Publishing Disertatia iliti razgovor… exactly in the štokavian dialect as a national and only language of all Serbs became a very turning point in the process of developing of the Croat national identity and nationalism with unpredictable consequences on the Croat-Serb relations in the future.

For the matter of better understanding the research-issue, it has to be noticed that the so-called (ex) Serbo-Croat language (an official title for the common standardized language of the Serbs and Croats at the time of both former Yugoslavias including and the present-day Bosniaks and Montenegrins) is divided into three basic dialects according to the form of the interrogative pronoun what: kajkavian (what = kaj), čakavian (what = ča), and štokavian (what = što). At the time of the Illyrian Movement, the kajkavian dialect was spoken in the north-western parts of Croatia proper (around Zagreb and Karlovac), the čakavian in the northern coast area and the islands of the eastern Adriatic shore (the Istrian Peninsula, area around Zadar, Rijeka, Split) and the štokavian within the area from the Austrian Military Border/Vojna Krajina (today in Croatia) in the north-west to the Šara Mt. (on the border between Kosovo-Metochia and Macedonia) in the south-east. The štokavian dialect (spoken in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and a biggest part of the present-day Croatia) is divided into three sub-dialects (the ekavian, ijekavian, ikavian) according to the pronunciation of the original Slavic vowel represented by the letter jat.[6]

J. Drašković’s manuscript, anyway, became not only an extensive (national, cultural and political) program of the Illyrian Movement, but at the same time, what is of the crucial importance, and an extensive program of the Croatian people as a nation.[7] His call for the creation of a Greater Illyria (but in fact of a Greater or united Croatia, composed by Croatia proper, Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Austrian Military Border, a Dalmatian city of Rijeka/Fiume, Dalmatia, Slavonia, Montenegro and Slovenia) on the basis of alleged Croatian state’s rights (iura municipalia) became an official program of the Illyrian Movement. Simultaneously, Drašković supported I. Derkos’ idea of creation of the common literal language for all Croats, but differently from Derkos, count J. Drašković proposed only the štokavian dialect (spoken at that time by all Serbs and only minority of Croats)[8] as the standardized language of the Croatian literature. This language he called as the Illyrian and accepted at the same time the so-called “Illyrian theory” upon “Croatian” (in fact, the South Slavic) ethno-linguistic origin according to the old “Croatian” (in fact, the South Slavic) tradition especially from Dalmatia.

A fact is that the Dalmatian and especially Ragusian (Dubrovnik) humanists in the 16th century accepted the old domestic Slavic thought and tradition that all Slavs (the Western, Eastern and Southern) originated in the Balkans and the Lower Danube region and that the South Slavs are autochthonous inhabitants of the peninsula. More precisely, the entire Slavic population had their own forefathers in the ancient Balkan Illyrians, Macedonians and Thracians. Principally, the ancient Illyrians were considered as the real ancestors of the South, Eastern and Western Slavs. Consequently, according to this belief but also and written mediaeval sources,[9] the Eastern and Western Slavic tribes emigrated from the Balkans and the Lower Danube region and settled themselves on the wider territory of Europe from the Elbe River in the west to the Volga River in the east.[10] However, the South Slavs remained in the Balkans – the peninsula that was considered as the motherland of all Slavonic peoples.[11] Subsequently, all famous historical actors originated in the Balkans were appropriated as the members of the Slavic race like Alexander the Great of Macedonia, Aristotle, St. Jerome (Hieronymus), Diocletian, Constantine the Great, SS. Cyril and Methodius, etc.

This theory traced back among the Roman Catholic South Slavs (today understood by the Croat historiography and ethnology as the ethnolinguistic Croats) to the humanist from Dalmatian city of Šibenik (at that time part of Venice), Juraj Šižgorić (Georgius Sisgoritius, 1420−1509), who wrote a short history of his native city in 1487 (De situ Illyriae et civitate Sibenici). In this work the author stressed that the ancient Balkan Illyrians (aborigines of the western and the central regions of the peninsula) have been a real ancestors of the modern Croats (and the rest of the South Slavs). According to his (wrong?)[12] opinion, St. Jerome, a native from Dalmatia, was a Croat who invented the first Slavic alphabet–Glagolitic one.

A famous Ragusian humanistic “poeta laureatus” Ilija Crijević (Aelius Lampridius Cervinus, 1463–1520), for instance, knew that the inhabitants of his born-city were of both the Roman and Slavic origins as he pointed it in his poem Oda Dubrovniku (“Ode for Dubrovnik”). Crijević in his work Super comoedia veteri et satyra et nova, cum Plauti apologia (“Apology for Plaut”) called the language of the ordinary people from Ragusa/Dubrovnik as “stribiligo illyrica” (“Illyrian solecism”), or as “scythica lingua” (“Scythian language”), following the tradition that ancient Slavs are called among other ethnic names and as the Scythians or Sarmatians. These two old Indo-European Iranian people lived during the time of the ancient Greeks and the Romans on the territory of the present-day Southern Ukraine and Russia (from the Volga River to the Danube River) and became in the Middle Ages synonyms for the Slavs.[13] In the song Qui proavi solio et patrueli culmine regnas, written for Bohemian-Hungarian King Władysław II Jagiello (the King of Bohemia, 1471–1516 and the King of Hungary, 1490–1516), Crijević considered the East Adriatic littoral as the “Illyrian coast”.[14] His contemporary, priest Mavro from Dalmatia, in his Glagolitic Breviary from 1460 indicated the town of Salona nearby Dalmatian city of Split as the birthplace of SS. Cyril and Methodius, who were in fact the brothers from Salonika. Moreover, these two “apostles of the Slavs”, according to the priest Mavro, were descendants from the Roman Emperor Diocletian, and Pope St. Gaius: “V Dlmacii Soline grdě. roistvo svetago Kurila i brata ego Metudie. ot roda Děokliciêna cěsara. i svetago Gaê papi”.[15]

A half a century later this Šižgorić’s idea of the Illyrian origin of the Croats and subsequently all Slavs (the Southern, Eastern and Western) was further developed by a Dominician friar from Dalmatian island of Hvar – Vinko Pribojević in his public lecture De origine successibusque Slavorum given in the city of Hvar in 1525 and published in Venice in 1532. For him, a Greek philosopher Aristotel, Macedonian King Alexander the Great, Roman Emperors Diocletian and Constantine the Great, St. Jerome, SS. Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius were Illyrians, i.e. the Slavs. Also Pribojević was the first to claim that three brothers, Czech, Lech, and Rus, were expelled from the Balkans and consequently became the founders of Bohemia and the Czechs, Poland and the Poles and Russia and the Russians and the other present-day Eastern Slavs (in fact the Rus’). Likewise Pribojević, Mauro Orbini, a Benedictine abbot from Dubrovnik who wrote an extensive history of Serbia (and in the lesser extend of Croatia and Bulgaria) under the title Il regno degli Slavi (published in Pesaro in 1601), saw the Slavs everywhere[16] and the Illyrians as “the noble Slavic race”. For him, the soldiers of Alexander the Great were the Slavs who spoke “the same language which is today spoken by the inhabitants of Macedonia” (the Muscovite Annals expresly state that the Rus’ are of the same race as were the ancient Macedonians). Finally, Orbini advocated the idea that the first Slavic alphabet, popularly called Bukvica, i.e. the Glagolitic script (for him second Slavic script – Cyrillic was invented by the saintly brothers from Salonika – Cyril and Methodius), was invented by St. Jerome, who was a Slav (the Illyrian), “since he was born in Dalmatia”.[17] M. Orbini repeated the old Dalmatian theory that three Balkan Slavic tribes, led by the brothers Czech, Lech and Rus’, moved northward and established the three new Slavic states – Bohemia (first ruled by Czech), Poland (first ruled by Lech) and Russia (first ruled by Rus’). For Orbini, modern Czechs, Poles and Russians likewise all South Slavs originated in the Balkan Illyrians.

However, a century later, Croat Pavao Ritter Vitezović (of the German origin like Ljudevit Gaj) went one step further: he claimed in 1700 and 1701 that all Slavs had a common progenitors in the ancient Illyrians who were in fact the ethnolinguistic Croats.[18] Vitezović’s main programatic idea upon unification of “all Croatia” (totius Croatia) became a century later an official political program of the leaders of the Croatian Illyrian Movement.[19]

It is important to notice that St. Jerome (Hieronymus) from Dalmatia was as well appropriated as a Slav and later on exclusively as a Croat. Consequently, the Latin-language Bible, which was written by St. Jerome and used by all Catholic Slavs in Europe was recognized by Dalmatian Catholics as achievement of the Slavic Croat. Moreover, St. Jerome was unjustifiably proclaimed as an inventor of the oldest Slavic alphabet – the Glagolitic one, named as “Jerome’s script” and subsequently this font became appropriated by the Croats as their own original and national characters that became used and by the other Slavonic peoples.

Thus, this first written Slavic language (named by the scholars as the Old Church Slavonic), and devised in fact by Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius in the middle of the 9th century,[20] became appropriated by the Croats in the Middle Ages and later on as a Croatian national and indigenous literal language. This belief founded an ideological doctrine in the later centuries for the claiming that all people (i.e. the Slavs) who used this language virtually belonged to the Croat ethnic community. In the late medieval period following a popular tradition about him, St. Jerome has been assumed as a spiritual progenitor of the Croats who translated a Hebrew and a Greek holy writings (sacre scripture) to both Latin and Slavonic languages.[21] Even the Roman Catholic Church accepted this popular opinion that St. Jerome was a founder of the Slavonic literacy.[22]

Obviously, the ideological foundations of the 19th century-Croat Illyrian Movement was the old South Slavic tradition, but supported by the historical sources as well, of the Balkan-Illyrian origin of all Slavs. However, the 19th century-Croat Illyrians arbitrary understood all Slavic Illyrians in fact as the ethnic Croats and therefore entire South (Balkan) Slavic populated territories and their historical-cultural inheritance as of the Croats. Therefore, as the greatest portion of the South Slavic inhabited territories at the Balkans were populated by the štokavian language speakers who composed as well as the biggest portion of the South Slavs, for the Croat Illyrians it was logically and even politically correct to chose exactly the štokavian as a new standardized national language for all Croats who were just hidden under the common South Slavic ethnic name of the Illyrians. However, this choice brought the Croats to direct political conflict with the Serbs who were only štokavian speakers and all Serbs have been (and are) only the štokavians contrary to the Croats who at the time of the Illyrian Movement were as the majority the kajkavians (as all Slovenes) and very tiny minority as the štokavian speakers.

The question of Dubrovnik (Ragusium/Ragusa)?

I. Derkos and J. Drašković promoted the štokavian dialect of Renaissance and Baroque literature of the Republic of Dubrovnik (Ragusium/Ragusa) as a Croatian one–an act which created among the Croats a national conscience upon the Ragusian cultural heritage as solely a Croatian one. However, a Serbian philologist Branislav Brborić (and many others) is in the opinion that the štokavian literature of Dubrovnik belongs to the Serbian cultural heritage as this dialect was and is a national Serbian language, but not the Croat one. According to his research, there are many Latin-language documents in the Archives of Dubrovnik in which the language of the people of Dubrovnik (the štokavian dialect of the ijekavian speech) is named as lingua serviana, but there is no one document in which this language is named as lingua croata.[23] B. Brborić claims further that for centuries citizens of Dubrovnik had some Serbian national consciousness and perception that their spoken language is Serbian. Among the inhabitants of the Republic of Dubrovnik, there was no Croatian ethnolinguistic consciousness before the Illyrian Movement and before Dubrovnik became included in the Roman Catholic Austrian Empire (Habsburg Monarchy) (from 1815).[24] In other words, from the time of Illyrian Movement, the process of Croatization of Dubrovnik, backed by the Habsburg authority, started.[25] Consequently, all Roman Catholic Serbs from Dubrovnik became the national Croats whose language was proclaimed by the leaders of the Illyrian Movement as a Croat language of the štokavian dialect and the ijekavian speech.[26] Therefore, after 1832, the Croatian national workers considered the people from Dubrovnik exclusively as the Croats and Ragusian history and culture as the Croat ones. Consequently, an anthology of Stari pisci hrvatski (Old Croatian Writers) where many Ragusian writers were published among others was printed in Zagreb from 1869 onwards. Nevertheless, the edition of this collection was criticized by the Serbs as a Croatian policy to appropriate the Serbian cultural heritage of Dubrovnik with the final political aim to include the territory of Dubrovnik, which never was a part of Croatia, into united Greater Croatia within the Austrian Empire or later since 1867, within Austria-Hungary.

Before Dubrovnik alongside with South Dalmatia was included into Croatia in 1945 for the first time in history due to the Communist rearrangement of the inner-territorial structure of Yugoslavia by her federalization,[27] two the most fervent defenders of the Serbian character of Dubrovnik against the Croat-favour claims by the leaders of the Illyrian Movement that this city-state (polis) belongs to the Croatian history and cultural heritage were the Roman Catholic Serb and famous philologist from Dubrovnik – Milan Rešetar (1860–1942) and the Serbian Orthodox priest – Dimitrije Ruvarac (1842–1931).

M. Rešetar concluded, after the extensive research in the Archives of Dubrovnik and as а person who very well knew Ragusan literature, that:

a) The people from Dubrovnik were and are the ethnic Serbs.

b) Their spoken and literal language is Serbian because they were speaking and mainly writing in the štokavian [28]

c) The citizens of Dubrovnik, however, did not call themselves the Serbs since for them the ethnic name Serbian was relating only to those who lived in the Serbian state: as Dubrovnik never was included in Serbia for that reason Ragusan people did not call themselves as the Serbs.

d) They, however, did not call themselves the Croats too as they did not ever live in any Croatia.

e) Usually, the Ragusan people understood themselves as Dubrovčani, i.e. as the citizens of the Republic of Dubrovnik (citizenship-identity).

f) The Serbs and the Croats do not speak the same (Serbo-Croat/Croat-Serb) language.

g) The Serbs and the Croats are two different peoples.[29]

I. Ruvarac claimed that after the Slavic migrations to the Balkans at the end of the 6th century, the Latin municipality (city) of Ragusium became Serbianized and as a consequence of this process, the city changed its name into a Slavic-Serbian–Dubrovnik (a Slavic dubrava=oak-forest). He refuted the Croatian claims advocated by the leaders of the Illyrian Movement that all inhabitants of Croatia, Dalmatia, Dubrovnik, and Slavonia can be only ethnolinguistic Croats regardless of their religion. However, D. Ruvarac was in opinion that the štokavian dialect is only Serbian national language which was spoken in Serbia, Dubrovnik, Slavonia, Dalmatia, Montenegro, and part of Croatia (the Military Border) by the Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Muslim believers. Especially he disapproved a Croatian idea that Slavonia (the region between the rivers of Sava and Drava, today included into the Republic of Croatia) is a part of Croatia because historically it was all the time a separate province with separate provincial name whose inhabitants were speaking the Slavonian language, as it is recorded in many historical documents. However, according to D. Ruvarac, the leaders of the Illyrian Movement proclaimed that the Croatian people and language (i.e., the kajkavian dialect, which was spoken in North-West Croatia only by the Roman Catholics) and the Slavonian people and language (i.e., the štokavian dialect, which was spoken in Slavonia by both the Orthodox and the Roman Catholics) as one Croatian-Slavonian people and language, which became soon called by the Croat philologists as only Croatian people and language. Thus, the Slavonians became the Croats and the Slavonian language became, therefore, the Croatian language. For D. Ruvarac, the same philological strategy was implied by the Croatian Illyrians in the case of Ragusian people and their Our or Slavic language (how they usually called their language). The final consequence of such politics by the leaders of the Illyrian Movement was a Croatization of Slavonia and a whole South Dalmatia including and Dubrovnik. D. Ruvarac’s standpoint can be summarized into three basic ideas:

a) The Serbs are all South Slavs whose mother tongue is the štokavian dialect regardless of their religion.

b) The Serbian and the Croatian languages, regardless of the fact that they are similar, are, in essence, two separate languages.

c) The genuine Croats are speaking the kajkavian and the čakavian “languages” (or today recognized as dialects), but not the štokavian one.[30]

According to the leading Slavic philologists from the end of the 18th century and the 19th century (a Serb Dositej Obradović, 1738–1811; Czech Pavel Josef Šafařik, 1795–1861; Czech Josef Dobrovský, 1753–1829; Slovene Jernej Kopitar, 1780–1844; and Slovene Franc Miklošič, 1813–1891), a genuine Croatian national language was only the čakavian, while the kajkavian was originally only the Slovenian national language, but in the course of time the kajkavian speakers who lived in Croatia accepted Croatian national feeling.[31] All opponents of political ideology and national program of the Illyrian Movement (the Serbs and Slovenes), concluded that the thesis of the Illyrian Movement that the Croats are speaking three “languages” (i.e., the kajkavian, čakavian and štokavian dialects as recognized today) should be refuted as a wrong one for the very reason that the leading principle in Europe from the end of the 18th century onwards was that one ethnic nation can speak only one language, but not several of them.[32]

Undoubtedly, I. Derkos’ and J. Drašković’s works and patriotism/nationalism framed the basic idea of the political requirement by the leaders of the Illyrian Movement – a political, linguistic and cultural unification of all “Croatian” lands. However, this idea was inspired by the work of a Croatian nobleman and professional writer of the German origin, Pavao Ritter Vitezović (1652–1713) who was the first among the Croats who advocated the concept of political unification of historical and ethnolinguistic Croatia and promoted the idea that the ancient Balkan people – the Illyrians, who lived in the Central and Western parts of the Balkan Peninsula at the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans, were the real ancestors of modern Croats and all Slavs.[33] In other words, he championed an idea that the Croats are descendants of the ancient Balkan Illyrians and that all Slavs originated exactly in the Croats. His formula was: Illyrian = Croat = Slav.

P. R. Vitezović divided the whole world into six ethnolinguistic, historical, cultural and geographical areas, civilizations and cultures:

- Germania, which embraced the whole German-speaking world: 1. The Holy Roman Empire of German Nation, headed by Austria, 2. The Kingdom of Sweden (Sweden, Norway, Finland), 3. Denmark, 4. East Prussia, 5. Curonian Isthmus (Kuršių neria) with Curonian Bay or Courish Lagoon (Kuršių Marios), 6. Memel (Klaipėda), and 7. Angliae regnum (Scotland, England, Wales, and Ireland).

- Italia cum parte Greciae (Italy with the part of Greece) referred to: 1. The Apennine Peninsula, 2. Corsica, 3. Sardinia, 4. Sicily, 5. Attica, 6. Peloponnesus (Morea), 7. The main number of the Aegean and the Ionian islands, 8. Malta, and 9. Crete.

- Illyricum, that was: 1. Almost the whole Balkans (except Attica and Peloponnesus with the adjoining islands), 2. Wallachia (Dacia and Cumania), 3. Transylvania, and 4. Hungary.

- Hispania, which was composed of: 1. Spain and Portugal, 2. Their European possessions, and 3. Their overseas colonies in Africa, Asia, Latin America with Florida and California.

- Sarmatia, that was: 1. A territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (the Republic of Two Nations), 2. Moldavia, and 3. Muscovy (i.e. the Russian Empire).

- Gallia, that was France.[34]

A real ideological source for such a division of the whole world was the popular Slavic idea that decisively influenced P. R. Vitezović, who recognized that all Slavs belonged to a single ethnolinguistic community (having the same ethnolinguistic origin). Nevertheless, the traditional idea of the Pan-Slavism was metamorphosed by him eleven years later into the idea of Pan-Croatianism and Greater Croatia. In fact, P. R. Vitezović claimed that all Slavs are the Illyrians who were autochthonous inhabitants of the Balkan Illyricum. For him it was clear that ancient Illyrians have been modern Croats and ancestors of all Slavs. This ideology of Croatian-Slavic ethnogenesis P. R. Vitezović developed in his work Croatia rediviva… (published in 1700) that was just an outline of more ambitious general history of the Croats and Croatia, i.e. entire Slavic population.

In Croatia rediviva… P. R. Vitezović divided a total territory of, according to his opinion, ethnic-historical-linguistic Croatia into two parts:

- Croatia Septemtrionalis (Northern Croatia).

- Croatia Meridionalis (Southern Croatia).

The boundary between these two Croatias was the Danube River.

Northern Croatia encompassed the entire territories of: 1. Bohemia, 2. Moravia, 3. Lusatia (Łužica or Łužyca in Eastern Saxony and Southern Brandenburg), 4. Hungary, 5. Transylvania, 6. Wallachia, 7. Muscovy, and 8. Poland with Lithuania.[35] The people who were living in Northern Croatia were divided into two groups: 1. The North-West Croats, called as the Venedicos (Wends), and 2. The North-East Croats, named as the Sarmaticos (Sarmatians). The Wends consisted of the Czechs, Moravians, and Sorbs (the Sorabi who lived in Lusatia), whereas the Sarmatians were living in Muscovy, Lithuania, and Poland,[36] i.e., they were the Rus’, Lithuanians and Poles.

P. R. Vitezović found that the ancestors of all Northern Croats – the Wends and Sarmatians – have been the White Croats (Belohrobatoi from the Byzantine historical sources) who lived in the early Middle Ages around the upper Dniester River and upper Vistula River, i.e., in Galicia and a Little Poland. A traditional name found in historical sources for White Croatia was Greater Croatia or an Ancient Croatia. In the time of P. R. Vitezović’s writing of Croatia rediviva… this territory was an integral part of the Republic of Two Nations (the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth).[37]

P. R. Vitezović’s Southern Croatia, or Illyricum (the Balkans), was subdivided into two parts: Croatia Alba (White Croatia), and Croatia Rubea (Red Croatia):

- Croatia Alba was composed of: Croatia Maritima (the central and maritime Montenegro, Dalmatia and East Istria), Croatia Mediterranea (Croatia proper and Bosnia-Herzegovina), Croatia Alpestris (Slovenia and West Istria) and Croatia Interamnia (Slavonia with part of Pannonia).

- Croatia Rubea consisted of: 1. Serbia, 2. the North-East Montenegro, 3. Bulgaria, 4. Macedonia, 5. Epirus, 6. Albania, 7. Thessaly, and 8. Odrysia (Thrace).[38]

There have been P. R. Vitezović’s frontiers of “limites totius Croatiae” (“boundaries of total Croatia”) settled by the ethnolinguistic Croats.[39] However, P. R. Vitezović recognized that his Greater Croatia and the Pan-Croatian national identity were not unified as a whole. In other words, he acknowledged differences in borders, names, emblems, and customs: “cum propriis tamen singularum limitibus etymo, Insignibus, rebusque ac magis memorabilibus populi moribus”.[40] After all, he believed that these distinctions were of less importance than the common Croatian nationhood of all of these peoples and lands. His apotheosis of the common Croat name especially for all South Slavs (the Illyrians) with regional and historic differences was expressed in P. R. Vitezović’s heraldic manual Stemmatographia… (published in 1701) where he presented all Croatian historical and ethnolinguistic lands in South-East Europe, like Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, etc.[41]

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

[1] M. Moguš, Povijest hrvatskoga književnoga jezika, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Globus, 1993, 138−140

[2] B. Šulek, Hrvatski ustav, Zagreb, 1883, 80.

[3] П. Милосављевић, Срби и њихов језик: Хрестоматија, Приштина: Народна и универзитетска библиотека, 1997. However, the Croatian historiography claims that those leading Slavic philologists developed their system of classification of the Slavonic languages on the “arbitrary” and falls basis [I. Perić, Povijest Hrvata, Zagreb: Krinen, 1997, 161].

[4] D. Pavličević, Povijest Hrvatske. Drugo, izmijenjeno i prošireno izdanje, Zagreb: Naklada P.I.P. Pavičić, 2000, 247.

[5] On imagined and self-proclaimed glorious Croat history with megalomania projections for the future, see [В. Б. Сотировић, “Хрватска ‘правашка’ историографија и Срби”, Serbian Studies Research, 4 (1), Novi Sad, Serbia, 2013, 173−188].

[6] V. Dedijer, History of Yugoslavia, New York, 1975, 103; B. Jelavich, History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983, 304–308. See more in [R. D. Greenberg, Language and Identity in the Balkans, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2008].

[7] J. Šidak et al., Hrvatski narodni preporod-Ilirski pokret, Drugo izdanje, Zagreb, 1990, 210.

[8] Б. Брборић, O језичком расколу. Социолингвистички огледи I, Београд, 2000, 324; Б. Брборић, С језика на језик. Социолингвистички огледи II, Београд, 2001, 321–326.

[9] J. Anisimov, Rusijos istorija nuo Riuriko iki Putino. Žmonės. Įvykiai. Datos, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2014, 19−21.

[10] About the western borders of the Slavic extension in the early Middle Ages, see [Engel J. (redactor), Großer Historischer Weltatlas. Zweiter Teil. Mittelalter, München, 1979, 36].

[11] Историја народа Југославије, Београд, 1960, 224−227.

[12] According to Jovo Bajić, St. Jerome was a Serb [Ј. Бајић, Блажени Јероним. Солинска црква и Србо-Далмати, Шабац: Бели анђео, 2003]. A Croat archeologist don Frane Bulić claimed that he was born in Bosansko Grahovo (the West Bosnia) – a region before 1995 populated by the Serbs. Nevertheless, St. Jerome was an Illyrian and therefore, according to the “Illyrian” theory of the Slavic origin, a South Slav.

[13] Hammond, Historical Atlas of the World, Maplewood, MCMLXXXIV, 3, 5; Westermann, Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte, Braunschweig, 1985, 11, 14–15, 22–23, 24; J. Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans. A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, Ann Arbor, 1994, 25−26. About a homeland of the Indo-Europeans, see [M. Gimbutas, “Primary and Secondary Homeland of the Indo-Europeans”, Journal of Indo-European Studies, 13, 1985, 185–202; P. J. Mallory, In Search of the Indo-Europeans. Language, Archeology and Myth, London, 1989; W. G. Davey, Indo European Origins, 2009; C. Watkins, The American Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011].

[14] C. Tadin, „Elio Lampridio Cerva“, Rivista Dalmatica, 3 (6), 1903, 265–278; M. Franičević, Povijest hrvatske renesansne književnosti, Zagreb, 1983, 310−313; I. Banac, Hrvatsko jezično pitanje, Zagreb, 1991, 29.

[15] M. Pantelić, „Glagoljski brevijar popa Mavra iz godine 1460”, Slovo, XV–XVI, 1965. 94–149; I. Banac, Hrvatsko jezično pitanje, Zagreb, 1991, 9.

[16] A. Schmaus, “Vincentius Priboevius”, Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, 1953, 254.

[17] M. Orbini, Kraljevstvo Slovena, Beograd, 1968, CXLII–CXLIX.

[18] Eq. Pavlus Ritter [Pavao Riter Vitezović], Croatia rediviva; regnante Leopoldo Magno Caesare, Zagreb, 1700. About historical development of the Slavic idea among the Croatian Baroque writers, see [J. Šidak, “Počeci političke misli u Hrvata – J. Križanić i P. Ritter Vitezović”, Naše teme, 16, 1972; T. Eekman, A. Kadić (eds.), “Juraj Križanić (1618–1683): Russophile and Ecumenic Visionary, The Hague, 1976].

[19] Lj. Gaj, “Horvatov Szloga y Zjedinjenye”, Danicza Horvatska, Slavonska y Dalmatinzka, 7. 1. 1835. About the problem of ideas of national identification of the South Slavs from the 16th to the 19th centuries, [I. Banac, “The Insignia of Identity: Heraldry and the Growth of National Ideologies Among the South Slavs”, Ethnic Studies, 10, 1993, 215–237]. About the ideological origins of the Illyrian Movement, from the Croat viewpoint, see [N. Stančić (ed.), Hrvatski narodni preporod, 1790–1848: Hrvatska u vrijeme Ilirskog pokreta, Zagreb, 1985].

[20] J. Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans. A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, Ann Arbor, 1994, 302.

[21] V. Štefanić, “Tisuću i sto godina od moravske misije”, Slovo, XIII, 1963, 34–36.

[22] However, many of the ancient and early mediaeval historical sources are using the term Illyrians as a syninim for modern ethnic-name of the Serbs and claiming at the same time St. Jerome from Dalmatia that was in fact of a Serb ethnic origin. There is a visible tendency, based on the sourses and tradition, among contemporary Serbian historians and ethnologists to claim that the Serbs are the oldest Balkan (indigenous) people, and evenmore that the original name for all Slavs has been – the Serbli. On this question, see for instance [О. Луковић-Пјановић, Срби…народ најстарији, I−III, Београд, 1994; Б. Влајић-Земљанички, Срби староседеоци Балкана и Паноније у војним и цивилним догађајима са Римљанима и Хеленима од I до X века, Београд, 1999; Д. Јевђевић, Од Индије до Србије. Прастари почеци српске историје. Хиљаде година сеобе српског народа кроз Азију и Европу према списима и цитатима највећих светских историчара, Београд, 2000 (reprint from 1961, Rome); М. Јовић, Срби пре Срба, Краљево, 2002; J. Бајић, Блажени Јероним, Солинска црква и Србо-Далмати, Шабац, 2003; Ј. И. Деретић, Д. П. Антић, С. М. Јарчевић, Измишљено досељавање Срба, Београд: Сардонија, 2009; М. Милановић, Историјско порекло Срба. Друго допуњено и проширено издање, Београд: Вандалија, 2011].

[23] A Yugoslav linguist Ranko Bugarski is in the opinion that in a sociolinguistic sense the dialects are not separate languages, but in a linguistic sense they are. According to him, a “dialect” is a “language” which lost the political battle, while a “language” is a “dialect” that won the political battle. In other words, it is only political decision if one “dialect” will be proclaimed and recognized as a “language”. For him, the most important criteria that create a difference between the “language” and the “dialect” is comprehensibility [R. Bugarski, Uvod u opštu lingvistiku, Beograd, 1996, 238–239]. A Serbian philologist and academic Ljubomir Stojanović (1860–1929) was in the opinion that around 20% of the South Slavic population cannot be exactly classified into one linguistic-national group according to their spoken language because they are speaking “mixture dialects” of two languages. Thus, there are “transitional zones” between the South Slavic languages [Љ. Стојановић, Приступна академска беседа, Београд, 11-I-1896].

[24] Б. Брборић, С језика на језик. Социолингвистички огледи, II, Београд, 2001, 43–44, 68.

[25] About the genesis of the idea of Serbian national identity among the Catholic intelligentsia of Dubrovnik and Dalmatia in the 19th century, see [I. Banac, “The Confessional “Rule” and the Dubrovnik Exception: The Origins of the “Serb-Catholic” Circle in Nineteenth-Century Dalmatia”, Slavic Review. American Quarterly of Soviet and East European Studies, 42 (3), Fall 1983].

[26] П. Милосављевић, Срби и њихов језик: Хрестоматија, Приштина: Народна и универзитетска библиотека, 1997, 13–41, 412–426, 466–476.

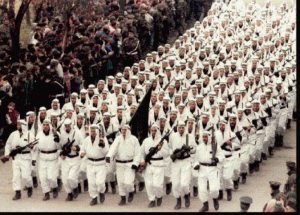

[27] It is true that the region of Dubrovnik before 1945 was given to the Province of Croatia (Banovina Hrvatska) within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in August 1939 according to the agreement reached by a leading Croat politician Vladimir Vlatko Maček and the Yugoslav PM Dragiša Cvetković (both of them have been non-Serbs) but, however, this agreement was never approved by the Yugoslav Parliament and was opposed by all Serbian leading political parties, politicians, church, intelligentsia, and public workers. Nevertheless, the agreement of August 26th, 1939 on Banovina Hrvatska was approved by the Yugoslav Royal Government and, therefore, it was created a kind of a Greater Croatia within Yugoslavia. The banovina was composed of the kajkavian Croatia, the štokavian Slavonia, West Srem, whole Dalmatia with Dubrovnik and huge territories in Bosnia-Herzegovina with a total population of 4,024,601 people (the 1931 census) [S. Srkulj, J. Lučić, Hrvatska povijest u dvadeset pet karata. Prošireno i dopunjeno izdanje, Zagreb: AGM−Hrvatski informativni centar−Trsat, 1996, 101−103]. However, the Serbs composed about 1/3 out of the banovina’s population. The borders of Banovina Hrvatska were created according to the Croat claim that all Roman Catholic štokavian speaking population in Yugoslavia have been the ethnic Croats − a viewpoint inherited from the Illyrian Movement’s ideology.

[28] A spoken language of the people from Dubrovnik was always the štokavian dialect, but their literature was written in four languages: the Latin, Italian, čakavian dialect, and štokavian dialect. The last two were “domestic languages”. The Čakavian dialect was used till the mid-15th century as the most fashionable literal language in the whole Dalmatia besides the Italian and Latin. However, from the mid-15th century, the writers from Dubrovnik mainly wrote in the štokavian dialect that became the language in which the most glorious Ragusan literature (the period of Baroque) was written. According to the most experts on the Slavic literature, probably, the štokavian Baroque literature of Dubrovnik gave the best examples of the Slavic Baroque literature.

[29] M. Решетар, Aнтологија дубровачке лирике, Београд, 1894; М. Решетар, “Најстарији дубровачки говор”, Годишњак Српске краљевске академије, 50, Београд, 1940; M. Rešetar, “Die Ragusanischen Urkunden des XIII–XV. Jahrhunderts”, Archiv für slawische Philologie, XVI Jahrgang, Wien, 1891; M. Rešetar, “Die Čakavština un deren einstige und jetzige Grenzen”, Archiv für slawische Philologie, XVI Jahrgang, Wien, 1891. However, during the time of royal Yugoslavia (1918–1941), M. Rešetar corrected his stand upon the Serbs and the Croats and their languages. Namely, under the strong influence of the official policy of “the integral Yugoslavism”, M. Rešetar became an advocate of an idea that the Serbs and the Croats were and are speaking the same language, and therefore they belong to the same people who just have two names (see more in [В. Новак, Антологија југословенске мисли и народног јединства, Београд, 1930]). Nevertheless, M. Rešetar two years before he died, returned to his original idea that the Serbs and the Croats are two different peoples who spoke two different languages and that Ragusian literal heritage belongs definitely to the Serbs, but not to the Croats.

[30] Д. Руварац, Ево, шта сте нам криви!, Земун, 1895. This book is important as the author is dealing with the ethnolinguistic division between the Serbs and the Croats.

[31] Д. Обрадовић, “Писмо Харалампију”, Живот и прикљученија, Нови Сад, 1783; P. J. Šafařik, Slowansky narodopis, Praha, 1842; P. J. Šafařik, Serbische Lesekörner, Pest, 1833; P. J. Šafařik, Geschichte der slawischen Sprache und Literatur nach allen Mundarten, Buda, 1826; J. Dobrovský, Geschichte der böhmische Sprache und Literatur, Wien, 1792/1818; J. Kopitar, Serbica, Beograd, 1984 (reprinted sellected works); J. Kopitar, “Patriotske fantazije jednog Slovena”, Vaterländische Bläter, 1810; F. Miklošič. “Serbisch und chorvatisch”, Vergleichende Gramatik der slawischen Sprachen, Wien, 1852/1879.

[32] See, for instance [A. Петровић, “Шта смо ми, шта ћемо бити, како ћемо се звати?”, Српски народни лист, № 24, 25, 26, 1839; Ђ. Николајевић, Српски споменици, Београд, 1840].

[33] On the ancient Balkan Illyrians, their culture and history, see [A. Stipčević, The Illyrians: History and Culture, Noyes Press, 1977; J. Wilkes, The Illyrians, Oxford UK−Cambridge USA: Blackwell, 1992].

[34] P. E. Ritter, Anagrammaton, sive Laurus auxiliatoribus Ungariae liber secundus, Vienna, 1689, 69–117.

[35] P. Ritter, Croatia rediviva: Regnante Leopoldo Magno Caesare, Zagreb, 1700, 10.

[36] P. Ritter, Croatia rediviva: Regnante Leopoldo Magno Caesare, Zagreb, 1700, 10.

[37] On the present-day Ukraine as a part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, see [A. Blanuca et al., Ukraina: Lietuvos epocha, 1320−1569, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2010]. On the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, see in [M. Jučas, Lietuvos Didžioji Kunigaikštzstė: Istorijos bruožai, Vilnius: Nacionalinis muziejus, 2016].

[38] P. Ritter, Croatia rediviva: Regnante Leopoldo Magno Caesare, Zagreb, 1700, 32.

[39] P. R. Vitezović, Mappa Generalis Regni Croatiae Totius. Limitibus suis Antiquis, videlicet, a Ludovici, Regis Hungariae, Diplomatibus, comprobatis, determinati, 1:550 000 (drawing in color), 69,4 x 46,4 cm., Croatian State Archives, Cartographic Collection, D I., Zagreb, 1699.

[40] P. Ritter, Croatia rediviva: Regnante Leopoldo Magno Caesare, Zagreb, 1700, 32; P. Ritter, Stemmatographia, sive Armorum Illyricorum delineatio, descriptio et restitutio, Vienna, 1701.

[41] P. Ritter, Croatia rediviva: Regnante Leopoldo Magno Caesare, Zagreb, 1700, 32; P. Ritter, Stemmatographia, sive Armorum Illyricorum delineatio, descriptio et restitutio, Vienna, 1701; I. Banac, “The Insignia of Identity: Heraldry and the Growth of National Ideologies Among the South Slavs”, Ethnic Studies, 10, 1993, 223–227.

Territory of Banovina Croatia in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1939-1941

Territory of Banovina Croatia in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1939-1941

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS