Views: 2038

On May 14, 1948, Israel declared its independence. Each May 15, Palestinians solemnly commemorate Nakba Day. Nakba means catastrophe, and that’s precisely what Israel’s independence has been for the more than 700,000 Arabs and their five million refugee descendants forced from their homes and into exile, often by horrific violence, to make way for the Jewish state.

Land Without a People?

In the late 19th century, Zionism emerged as a movement for the reestablishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Although Jews ruled over kingdoms there more than 2,000 years ago, they never numbered more than around 10 percent of the population from antiquity through the early 1900s. A key premise of Zionism is what literary theorist Edward Said called the “excluded presence” of Palestine’s indigenous population; a central myth of early Zionists was that Palestine was a “land without a people for a people without a land.”

In the late 19th century, Zionism emerged as a movement for the reestablishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Although Jews ruled over kingdoms there more than 2,000 years ago, they never numbered more than around 10 percent of the population from antiquity through the early 1900s. A key premise of Zionism is what literary theorist Edward Said called the “excluded presence” of Palestine’s indigenous population; a central myth of early Zionists was that Palestine was a “land without a people for a people without a land.”

At its core, Zionism is a settler-colonial movement of white, European usurpers supplanting Arabs they often viewed as inferior or backwards. Theodore Herzl, father of modern political Zionism, envisioned a Jewish state in Palestine as “an outpost of civilization opposed to barbarism.” Other early Zionists warned against this sort of thinking. The great Hebrew essayist Ahad Ha’am wrote:

We… are accustomed to believing that Arabs are all wild desert people who, like donkeys, neither see nor understand what is happening around them. But this is a grave mistake. The Arabs… see and understand what we are doing and what we wish to do on the land. If the time comes that [we] develop to a point where we are taking their place… the natives are not going to just step aside so easily.

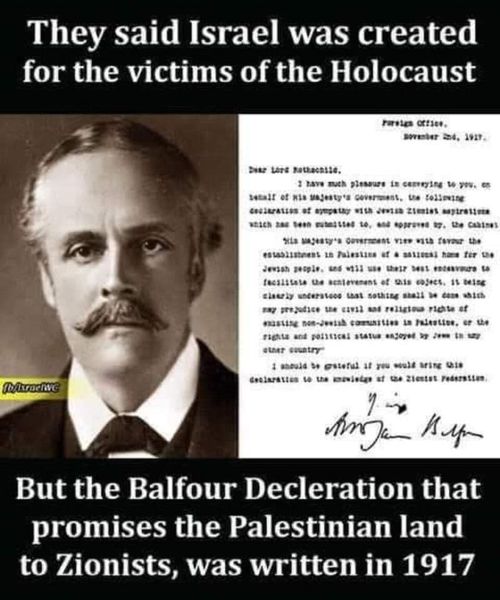

Jewish migration to Palestine increased significantly amid the pogroms and often rabid antisemitism afflicting much of Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century. As control of Palestine passed from the defeated Ottoman Turks to Britain toward the end of World War I, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour declared “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” Israelis and their supporters often cite the Balfour Declaration when defending Israel’s legitimacy. What they never mention is that it goes on to state that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.”

Those “existing non-Jewish communities” still made up more than 85 percent of Palestine’s population at the time. As Zionist immigration swelled in the interwar years, conflict between the Jewish newcomers and the Arabs who had lived in Palestine for centuries was inevitable.

The Palestine Problem

Some Arabs reacted to the massive influx by rioting and attacking Jews, who responded by forming militias. Hundreds of Jews and Arabs were murdered in a series of clashes and massacres throughout the 1920s, and as yet another wave of Jewish migration surged into Palestine following the rise of Hitler, Britain formed the Peel Commissionto examine the “Palestine problem.” The commission proposed a “two-state solution” — one for Jews, another for Arabs, with Jerusalem remaining under British control to protect Jewish, Christian and Muslim holy sites.

As Arab attacks and Jewish retaliation escalated, an exasperated Britain issued the 1939 MacDonald White Paper, which limited Jewish immigration to Palestine. It emphatically stated that the “Balfour Declaration… could not have intended that Palestine should be converted into a Jewish state against the will of the Arab population of the country.” From then on, Jewish militias, who by now had gone on the offensive and were initiating often unprovoked attacks on Arabs, targeted British occupiers as well.

The two most infamous Jewish terror militias were Irgun and Lehi, led respectively by Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir, both future Israeli prime ministers. Irgun was by far the most prolific of the two terror groups, carrying out a string of assassinations and attacks meant to drive out the British. On July 22, 1946, Irgun fighters bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 people, including 17 Jews, an attack still celebrated in Israel today. They bombed and shot up crowded markets, trains, cinemas and British police and army posts, killing hundreds of men, women and children. Meanwhile, Lehi assassinated British minister of state Lord Moyne in Cairo in 1944, while planning to kill Winston Churchill as well.

“No Room for Both”

With it soldiers, police, officials and, increasingly, its reputation constantly under attack and its resources strained to the breaking point after World War II, Britain withdrew from Palestine in frustration in 1947. The “Palestine problem” was handed off to the fledgling United Nations, which, under intense United States pressure, voted to partition the territory. The Arabs were not consulted. Jews, who comprised just over one-third of Palestine’s population, would get 55 percent of its land. Arabs were enraged.

Jews rejoiced. There was, however, a huge problem with the UN partition plan. If the state of Israel was to be both Jewish and democratic, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians would have to leave. Forever. Years earlier, Jewish National Land Fund director Joseph Weitz said:

Among ourselves it must be clear that there is no room for both people in this country… and there is no way besides transferring the Arabs from here to neighboring countries… We must not leave a single village, a single tribe.

“A Bit Like A Pogrom”

To that end, David Ben-Gurion, who would soon become Israel’s first prime minister, and his inner circle drafted Plan Dalet, the “principle objectiveof the operation [being] the destruction of Arab villages,” according to official orders. At times the mere threat of violence was enough to coerce Arabs from their homes. Sometimes appalling slaughter was required to get the job done. In the most notorious of what Israeli historian Benny Morris has identified as Nakba 24 massacres, more than 100 Arab men, women and children were killed by Jewish militias at Deir Yassinon April 9, 1948. One 11-year-old survivor later recalled:

“They blew down the door, entered and started searching the place… They shot the son-in -law and when one of his daughters screamed, they shot her too. They then called my brother and shot him in our presence and when my mother screamed and bent over my brother, carrying my little sister, who was still being breast-fed, they shot my mother too.”

“To me it looked a bit like a pogrom,” confessed Mordechai Gichon, an intelligence officer in the Haganah, which would soon become the core of the Israel Defense Forces. “When the Cossacks burst into Jewish neighborhoods, then that should have looked something like this.” Widespread looting and brutal and often deadly rapes were also reminiscent of antisemitic pogroms, with Jews now the aggressors instead of the victims.

News of Deir Yassin spread like wildfire through Palestine, prompting many Arabs to flee for their lives. This is exactly what Jewish commanders — who would play self-described “horror recordings” of shrieking women and children on loudspeakers when approaching Arab villages — wanted. Attacking Jewish militias typically gave most of their victims room to escape; commanders generally preferred a fright-to-flight strategy over wanton slaughter.

“Like Nazis”

Jewish ethnic cleansing of Palestine accelerated when Arab armies from Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Iraq invaded with the intent of smothering the nascent state of Israel in its cradle. On July 11, 1948, future Israeli foreign and defense minister Moshe Dayan led a raid on Lydda in which over 250 Arab men, women, children and old people were killed with automatic weapons, grenades and cannon. What followed, on future prime minister Yitzhak Rabin’s orders, was the wholesale expulsion of Lydda and Ramle. Tens of thousands of Arabs fled in what became known as the Lydda Death March. Israeli reporter Ari Shavit wrote:

Children shouted, women screamed, men wept. There was no water. Every so often, a family… stopped by the side of the road to bury a baby who had not withstood the heat; to say farewell to a grandmother who had collapsed from fatigue. After a while, it got even worse. A mother abandoned her howling baby under a tree. [Another] abandoned her week-old boy.

The international community was horrified and outraged by the Jewish atrocities of 1948-49. In the United States, a prominent group of Jews including Albert Einstein blasted the “terrorists” who attacked Deir Yassin. Others compared the Jewish militias to their would-be German destroyers, including Aharon Cizling, Israel’s first agriculture minister, who lamented that “now Jews have behaved like Nazis and my entire being is shaken.”

The international community was horrified and outraged by the Jewish atrocities of 1948-49. In the United States, a prominent group of Jews including Albert Einstein blasted the “terrorists” who attacked Deir Yassin. Others compared the Jewish militias to their would-be German destroyers, including Aharon Cizling, Israel’s first agriculture minister, who lamented that “now Jews have behaved like Nazis and my entire being is shaken.”

Jews indeed behaved something like Nazis as they expelled or exterminated Arabs for their own lebensraumin Palestine. By the time it was all over, over 400 Arab villages were destroyed or abandoned, their residents — some of whom still hold the keys to their stolen homes — never to return. Moshe Dayan, one of Israel’s most exalted heroes, confessed in all but name to Israel’s ethnic cleansing in a 1969 speech:

“We came to this country, which was already populated by Arabs, and we are establishing… a Jewish state here. Jewish villages were built in place of Arab villages. You do not even know the names of these Arab villages, and I do not blame you, because those geography books no longer exist. Not only do the books not exist, the Arab villages are not there either… There is not one place built in this country that did not have a former Arab population.”

War on Truth & Memory

Today such honesty is sorely lacking, both among most Israeli Jews and their US coreligionists and supporters. In addition to efforts to silence and even outlaw peaceful protest movements like the growing worldwide Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) effort, Zionists and their apologist allies — some with their own competing religious agenda — have aggressively sought to erase the Nakba from memory. This is accomplished by denying Israeli crimes and by tarring critics with allegations of antisemitism.

Special vitriol is reserved for the “self-hating”Jews who dare shine light on Israeli atrocities. Teddy Katz, a graduate student at Haifa University and ardent Zionist who uncovered the mass slaughter of 230 surrendering Arabs at Tantura on May 22, 1948, was sued, publicly humiliated, forced to apologize and stripped of his degree for the “offense” of telling the ugly, uncomfortable truth. The Israeli government even went as far as banning diaspora Jews who are too critical from making the “birthright return” to Israel granted to every other Jew in the world.

No Return, No Retreat

Speaking of the right to return, as Nakba refugees fled Palestine, often to settle in squalid camps in neighboring countries, the United Nations passed Resolution 194, which guaranteed that every Palestinian refugee could return to their home and receive compensation for damages. None ever did. Israel ignored this and dozens of other UN resolutions over the coming decades, its impunity ensured by massive and unwavering US support.

Enabled and emboldened, Israel now marks 70 years of statehood and over half a century of illegal occupation in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Today, Israel’s illegal Jewish settler colonies are the spear-tip of what critics call its slow-motion ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Its Jews-only settlements and roads, separation wall and ubiquitous military checkpoints are, according to Jimmy Carter, Desmond Tutu and others, the foundation of an apartheid state. Its periodic invasions of Gaza, with their 100-1 death toll disparities, their slaughter of entire families and enduring economic privation, are globally condemned as war crimes.

Enabled and emboldened, Israel now marks 70 years of statehood and over half a century of illegal occupation in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Today, Israel’s illegal Jewish settler colonies are the spear-tip of what critics call its slow-motion ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Its Jews-only settlements and roads, separation wall and ubiquitous military checkpoints are, according to Jimmy Carter, Desmond Tutu and others, the foundation of an apartheid state. Its periodic invasions of Gaza, with their 100-1 death toll disparities, their slaughter of entire families and enduring economic privation, are globally condemned as war crimes.

Yet through it all, the Palestinian people endure, despite the overwhelming odds against them. The more honest voices among earlier generations of Zionists foresaw this. Echoing Ahad Ha’am’s 1891 warning that “the natives are not going to just step aside so easily,” Ben-Gurion later acknowledgedthat “a people which fights against the usurpation of its land will not tire so easily.” Seventy years later, neither Palestinians nor Jews have tired so easily, and the world is no closer to solving the “Palestine problem.” Meanwhile, Jews, Arabs and the wider world brace for the next inevitable explosion. This is colonialism’s deadly legacy.

Originally published on 2018-05-11

About the author: Brett Wilkins is editor-at-large for US news at Digital Journal. Based in San Francisco, his work covers issues of social justice, human rights, and war and peace.

Source: Counter Punch

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.