Views: 1064

With respect to Greece’s role in the Mediterranean security system, the multilateralist formula applied to the region including the Balkans as well as is the orienting principle for the Greek foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. Since 1994, the opportunities for NATO’s and EU’s initiatives were more than apparent for Athens when Greece (wrongly) understood the Euro-Atlantic community as a fundamental security player for the extending the values of security and co-operation into this structurally unbalanced region. During the Cold War, the Greek policy-makers also found (wrongly) since 1952 that the US-led NATO offered allegedly excellent opportunities for the protection of basic national aims but the real disappointment came after Turkey’s military invasion of Cyprus in 1974 as the punishment did not come either from the US or the NATO (both Greece and Turkey are NATO’s member-states since 1952).

The Main Problematic Issues

The end of the Iron Curtain in 1989 concerning the European and Mediterranean security system was not so profitable for Greece as it was in the case, for instance, for Turkey. In fact, the dissolution of the USSR and the Warsaw Pact for Greece were not of big importance as from 1974 Greece have constant and crucial friction with Turkey, one of the members of the NATO. Relations with Turkey are aggravating constantly from 1974 taking into consideration alongside the Cyprus crisis and the questions of the border issue at the Balkans, the 1913−1923 Greek genocide’s recognition by Ankara that was committed in Anatolia by the Ottoman government,[1] and the question of the investigation and exploitation of the natural gas and oil in the Aegean Sea. We also have to consider that the Greek minority in Istanbul suffered heavily from the imposition of discriminatory taxation during the WWII. The anti-Greek policy of the Turkish Government continued even after 1952 when both countries due to shared perception of the Soviet treat joined the NATO but the riots inspired by the Turkish authorities against the Greek community of Istanbul erupted resulting in a number of deaths and the damage to property was on a massive scale as over 4.000 Greek shops, 100 hotels and restaurants and 70 churches were damaged or destroyed.[2] As a matter of good illustration of the diplomatic Greek-Turkish war since 1974 it can be the case when during the First Gulf War in 1990, Greece’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs compared Iraq’s military invasion of Kuwait with Turkey’s occupation of North Cyprus in 1974.[3]

We have to keep in mind that Greece is a member state of both the NATO and the EU. However, due to the open diplomatic-political conflict with another NATO’s member state Turkey over Cyprus, Greece is basically trying since its membership to the EU in 1981 (at that time it was the European Community) up today to solve this issue outside the NATO but within the EU as Turkey is still on EU’s membership waiting list (candidate state since 1999). Nevertheless, the Greek attitude toward the NATO since 1974, and to US’s administration as well as, is mainly in the direct relations to the Cyprus problem. The fact that Greece did not resolve this problem within the NATO was one of the focal political reasons for Athens to turn diplomatic efforts toward the EU where the Greek position was better than in the NATO where the Americans are dictating their own rules of the game according to which, Greece’s geopolitical and geostrategic position is incomparable with the Turkish one and, therefore, Washington apparently supported Ankara during the 1974 Cyprus crisis. However, even within the EU, or Western European countries, the Greek position was radically reduced with a re-creation of the Western European Union (the WEU) in which Greece was not accepted for the first time alongside with Denmark and Ireland. It is important to stress that the Greek standpoint toward a re-emergence of the WEU was that this organization was re-established primarily with the purpose to marginalize the Greek position within the EU, but also and within the NATO. Anyway, the Greek feelings were that the WEU was carrying out an anti-Greek and pro-Turkish policy.[4]

The WEU/EU And Greece

We have to keep in mind that the WEU was a military alliance for the purpose to effect collective security for its member states which emerged from the Treaties of Dunkirk (1947) and Brussels (1948). It was founded in 1954 with its effectiveness from May 6th, 1955 in conjunction with the admission of West Germany into the NATO. The WEU was, in fact, an added forum of security and cooperation in the face of German rearmament. Nevertheless, its existence was overshadowed by US’s led NATO and through the American military involvement in West Europe. Its members were Belgium, West Germany, France, Greece (since 1994), the UK, Italy, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, Spain (since 1989), and Portugal (since 1989). Since the end of the Cold War, there were ideas to transform the WEU into the military forces of the EU. However, this idea was not realized as five EU’s member states remained outside the WEU. In 1999 and 2000, its member states decided to transfer its operative functions into the EU for the sake to make stronger its European Security and Defence Policy.

A decision that Greece can be accepted into the WEU was done in Maastricht in December 1991. This decision was realized in March 1995. However, according to the Article 5 of the founding act of the WEU (the “Brussels Contract”), the members of the WEU are not obliged to intervene in the case of a conflict between two or more members of the NATO. The value of the article was confirmed in Petersberg in June 1992, by the Ministerial Council of the WEU. The Greeks explained this decision as “non-solidarity” with Athens and moreover as “giving support to Ankara for military action” against Greece. Probably, because of the pro-Turkish policy by the NATO as well as because of non-support of Greece in conflict with Turkey by the WEU and the EU, Athens decisively supported the territorial integrity of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (the SFRY) from the very beginning of the Yugoslav conflict and civil war (1991−1995). Actually, Greek support of the Yugoslav integrity was pointed against a German pressure in December 1991 that the EU should recognize Slovenia and Croatia as the independent states. Differently from Berlin, Athens was evaluating Slovenia’s and Croatia’s self-proclamation of independence (June 25th, 1991) as a secession from the purely legal point of view. However, the Greek attitude had and very practical viewpoint as Athens was scared that the conflict in former Yugoslavia can embrace the whole region, particularly concerning the problem of the Albanians, who had territorial pretensions on Greece in order to create a Greater Albania, and the question of state name of Yugoslav Macedonia and its independence. Actually, the Macedonian Question was the crucial problem for the Greek diplomacy dealing with the regional affairs of the Balkans after 1991. Athens was since 1993 in a strict opinion that a state with the name of (the Republic of) “Macedonia” is a permanent source of conflicts and instability on the Balkan Peninsula. A current compromise (reached in fall of 2018) between Athens and Skopje about the state-name of ex-Yugoslav Macedonia (the Republic of North Macedonia) is more satisfying Macedonian than Greek side and it is a big question if the Greeks are going finally to accept it (after the plebiscite which are going to be accompanied by massive anti-governmental demonstrations like those in Athens on January 20th, 2019) what practically means that the Macedonian agony can be prolonged for a longer period of time followed by the renewing of the inter-ethnic conflicts in Macedonia between the Slavs and the secessionist Albanians (a Kosovo syndrome).

Nevertheless, on the other hand, Turkey qualified the civil war in former Yugoslavia as Serbia’s aggression on Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia, respectively.[5] In other words, the Yugoslav conflict 1991−1995 in the Turkish eyes was a policy of the Serbian aggressive nationalism against the (Slavic) Muslim population of Bosnia-Herzegovina and (Muslim) Albanians in Kosovo.[6] According to Sabri Sayari, the final goal of this Serbian aggressive nationalism was a creation of a Greater Serbia.[7] During the war, a Turkish President Turgut Özal (1989−1993) had a great deal to create an anti-Serbian coalition either on the Balkans (a Muslim Green Corridor) or out of it. It was one of the reasons for a Turkish strengthening of political and economic relations with Bulgaria, Albania, and Macedonia but alongside with these bilateral relations, Ankara wanted to marginalize a political role of Athens in the Balkans.

A former Yugoslav (Socialist Republic) of Macedonia became a new source of deterioration of relations between Turkey and Greece since 1991. Turkey recognized Macedonia as an independent state in February 1992, only several hours later after the Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs applied to his Turkish colleague to wait for the final decision by the EU about the Macedonian case of independence.[8] A great victory of Turkey in the Balkan policy in the 1990s was a UN’s decision that, among other international peace-keeping forces, in Bosnia-Herzegovina can participate as well as the Turkish soldiers. This decision was characterized by Greece as Turkey was playing a role of the puppet of the American supervision on the Balkans. In essence, Greece even after the end of the Gulf War in 1990 felt that a strengthening of the Turkish role in the Balkan affairs can be a great threat for the peace process and political stability on the Balkans as well. In general, both of them, either Turkey or Greece, are in the opinion that alone they cannot solve their regional problems and that they should find crucial support from aside. The Cypriot case of 1974 approved such opinion clearly to be true. For sure, that was the most serious crisis by far in both Greece’s and Turkey’s foreign relations after the WWII.

The 1974 Cyprus Crisis

In Greece in the 1960s, sharp disagreement about the power of the monarchy in the military affairs, and impending army’s reforms designed to reduce the military’s role as supreme actor on the political scene, led to an army coup in 1967 followed by the establishment of the new government composed by the so-called “Black Colonels” or “Greek Colonels”. That was a military regime from 1967 to 1974 which was brought about by a military coup on April 21st, 1967, ostensibly in order to secure Greece against a Communist takeover and, therefore, the new regime enjoyed silent but full support by the US’ administration. The colonels occupied the crucial posts in the Government, administration, and military with their own political supporters, who were in majority of cases ill-qualified to govern the country but have been politically loyal. As a consequence, there were administrative chaos, repression, censorship, and violation of human rights. The Colonels’ regime, for sure, was even more inefficient than that of their predecessors and their flagrant violation of human rights, with silent support by Washington, tremendously increased international opposition followed by increased internal senses of anti-Americanism.

The national policy was one of the most important issues by the Colonels’ junta as it was exposed in 1973 when due to the divisions within the military dictatorship the leader of the military junta regime, Georgios Papadopoulos, was deposed in a coup by Brigadier General Dimitrios Ioannides who strongly supported the unification of Cyprus with Greece.[9] The Cyprus crisis, which died down in 1964, flared up again in 1967 when the new colonels’ junta Government in Athens encouraged the Greek patriots in Cyprus to enforce the political agitation for the union (enosis) of the island with Greece. The junta in Athens engineered a coup d’état against the President of Cyprus Makarios III by the Cypriot national guard, which went on to proclaim enosis. Ankara demanded diplomatic intervention by the powers who had guaranteed both Cypriot Constitution and state’s independence in 1960 (the UK, Greece, and Turkey) but when other two states refused to act Turkish armed forces acted alone.[10]

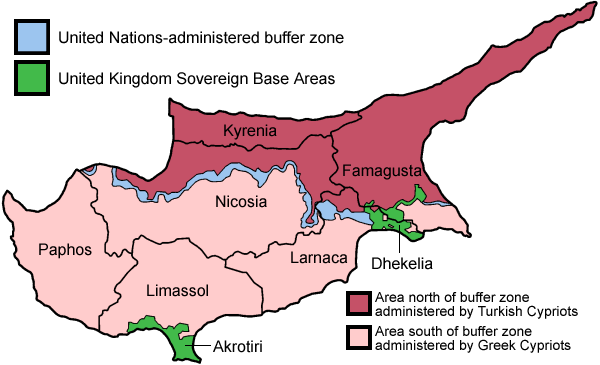

Harassed by international pressure and internal demonstrations, which were at the same time and anti-American, Ioannides’ attempt in 1974 to get nationalist support in his attempt to overthrow Archbishop Makarios III of Cyprus backfired, as this finally led directly to the Turkish military invasion of the northern part of the island and Turkish occupation of 40% of Cyprus that violates all kind of international laws but the US’ administration kept silent. After this case, the military regime in Greece became untenable, forcing Brigadier Dimitrios Ioannides to ask Konstantinos Karamanlis to supervise a return to democratic rule. In retaliation against King Constantine’s initial support for the “Black Colonels”, 69.2% voted in a plebiscite of December 8th, 1974 for the abolition of the monarchy which lost the US’s crucial support which was, in fact, transferred to Ankara during the Cyprus crisis of 1974. Washington, therefore, did not use any pressure to the Turkish Government to stop ethnic cleansing of North Cyprus (after the invasion on July 20th, 1974) which was, in fact, a continuation of the 1913−1923 Greek genocide and the 1974 ethnoterritorial division of Cyprus is, basically, the American design how to solve the Cyprus crisis – the same principle was later in 1995 applied by Clinton’s administration in the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina (the Dayton Accords). Subsequently, over 200.000 ethnic Greeks were expelled from the Turkish army and were replaced by new settlers from Anatolia. In 1983 a formally independent Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus was proclaimed and up today recognized only by Turkey. Nevertheless, the 1974 Cyprus crisis clearly demonstrated that without crucial support by some great (super) power is not possible to realize the national goals in foreign policy.

Greece’s Priorities in Foreign Policy After 1974

After the Cyprus debacle in July 1974, the focal priorities of Athens concerning the Greek foreign policy became pointed towards the relations with post-Communist Balkan neighbors and with the non-EU’s and non-NATO’s member states of the region of the Mediterranean Sea.[11] Therefore, the Balkans became one of the most important crucial points of the Greek foreign policy since the end of the Cold War primarily due to the new geopolitical environment that was created by the destruction of ex-Yugoslavia. In the case of the Balkans, after a painful interlude in 1992−1994 of close diplomatic involvement in a regional conflicts, Greece has opted for a multilateral foreign policy together with its EU’s, WEU’s, NATO’s, and OSCE’s partners designed to contribute to successful politics of transition towards democracy and liberal market economy in each of the states north of its borders but in practice it meant that Athens surrendered to Washington’s dictated a new post-Cold War’s order in the region. The consequences of such reality are today quite visible as Greek’s role in the regional affairs is quite marginalized, especially in comparison with the role and influence of Turkey at the Balkans. The last diplomatic regional defeat of Greece is an agreed name changing of Macedonia in the fall of 2018 (the Republic of North Macedonia) that was imposed by Washington and Brussels at the expense of the Greek national interest.

Protest in Athens against the name of the “Republic of North Macedonia”

Protest in Athens against the name of the “Republic of North Macedonia”

Nevertheless, the Greek-Turkish relations since 1973 are of the crucial importance for Athens up today as Greece finally in that year received extremely painful slam by Ankara. Namely, in 1973, Turkey initiated a policy contesting Greek sovereign rights and in order to realize her foreign policy’s objectives, Ankara “ignores fundamental provisions of International Law and existing international treaties”.[12] Such policy, in fact, founded bilateral affairs of Greece and Turkey on a very dangerous course for the next several decades. Year after year, since 1973, Ankara’s claims over the sovereignty of Greece were constantly increasing. Up today, Turkey disputes the width of the Greek territorial waters, the delimitation of the continental shelf in the eastern portion of the Aegean Sea, the Greek National Airspace, the Athens Flight Information Region, the Greek sovereignty over a number of islands and islets in the Aegean Sea close to Turkey’s border, and, finally, the island of Gavdos that is close to the island of Crete. Furthermore, Turkey demands from Greece to demilitarize the islands of Limnos and Samothrace in the northern section of the Aegean Sea, as well as the four largest islands in the eastern section of the same sea: Lesbos, Ikaria, Chios, and Samos. The same requirements are put over the Dodecanese Islands which Greece received after the WWII from Italy. Finally, Ankara is charging Athens with blocking its membership to the EU and for denying her dialogue to resolve all pending bilateral problems.

The Fatal Mistake

From the present-day perspective, the fatal mistake of the Greek Cold War’s foreign policy’s priorities was a decision to keep as better as relationships with the USA. One can properly argue that the profile of this position and the relationships from 1947 (the Truman Doctrine) to 1974 (the collapse of Greece’s policy over Cyprus) was of the classic patron-client variety. The USA, a dominant superpower, and Greece, a strategically located but internally divided small state, could not have avoided the center-periphery dependence of the bilateral relationship. It was decisive American intervention during the Greek Civil War of 1946−1949 which prevented a Communist take-over. The victorious side was indeed grateful, and Harry Truman’s statue was erected overlooking a busy central avenue in Athens.[13] However, at the same time, the vanquished but sizeable minority viewed the USA as an “evil empire” responsible for their final defeat in 1949. The rest of Greece’s society is going to accept such attitude toward Washington too late: only after July 1974.

From 1949 till 1974 the Greek-USA relations were crucially affected by a constantly escalating Greek-Turkish conflict over the fate of the island of Cyprus. Perceptions in Greece were that Washington is systematically tilting in favor of Ankara for the reason that Turkey’s geostrategic value was heavily exaggerated by the American strategic thinkers (and warmongers). Anti-Americanism in Greece assumed greater dimensions as a result of Washington’s support of the military junta in Athens during the 1967−1974 period when Greece was placed under the oppressive regime of the “Black Colonels” who became the main political force accused of the Cyprus catastrophe in July 1974. Therefore, it is not surprising that in the years following the restoration of democracy in Greece after 1974 the anti-American rhetoric is accepted and promulgated by a majority of the politicians who too late understood what was behind the US’s crucial intervention in the 1946−1949 Greek Civil War followed by the Greek-American post-war friendship.

Ex-University Professor

Vilnius, Lithuania

Research Fellow at the Center for Geostrategic Studies

Belgrade, Serbia

www.geostrategy.rs

sotirovic1967@gmail.com

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2024

Personal disclaimer: The author writes for this publication in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.

[1] On the Greek genocide, see in [Theodora Ioannidou, The Holocaust of the Pontian Greeks: Still an Open Wound, Meditera Books, 2016; Eric Sjöberg, The Making of the Greek Genocide: Contested Memories of the Ottoman Greek Catastrophe, New York−Oxford, Berghahn Books, 2017].

[2] Richard Clogg, A Concise History of Greece, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992, 153.

[3] On the Cyprus conflict, see in [Jan Asmussen, Cyprus at War: Diplomacy and Conflict During the 1974 Crisis, London: I.B.Tauris, 2008; Michális Staurou Michael, Resolving the Cyprus Conflict: Negotiating History, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009].

[4] Yannis G. Valinakis, “Southern Europe Between Détente and New Threats: The View from Greece”, Roberto Aliboni (ed.), Southern European Security in the 1990s, London: Pinter Publishers, 1992, 62−63.

[5] About the Turkish politics concerning the Yugoslav case in the 1990s, see in [Albert Bininašvili, „Turkey and the Balkans in the 1990s“, Stefano Bianchini, Paul Shoup (eds.), The Yugoslav War, Europe and the Balkans: How to Achieve Security?, Ravenna: Longo Editore Ravenna, 1995, 157−164].

[6] About the politics of Serbia during the time of the destruction of ex-Yugoslavia in the 1990s from the Western academic perspective, see in [Robert Thomas, The Politics of Serbia in the 1990s, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999].

[7] Sabri Sayari, “La Turque et la crise Yugoslave”, Politique Etrangere, 2, 1992, 315.

[8] Ekavi Athanassopoulou, Turkey and the Balkans, “The International Spectator”, 4, Roma 1994, 57.

[9] This idea of unification with the “motherland” Greece was ideologically based on the concept of “nationality” developed in West Europe in the 19th century. To be more precise, this concept and term were introduced into the language of European nationalism by the Italian Giuseppe Mazzini who claimed that the existence of a collective nationality required that all those identified it should gain their own political sovereignty within a united national state [Alexander Kitroeff, “Greek Nationhood and Modernity in the 19th c.”, Balkan Studies, 40 (1), 1999, 29−31].

[10] Erik J. Zürcher, Turkey: A Modern History, London−New York: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, 1994, 289.

[11] Theodore Couloumbis, “Strategic Consensus in Greek Domestic and Foreign Policy since 1974”, Eurobalkans, Spring 1998, 38.

[12] “Greek-Turkish Relations”, Eurobalkans, Spring 1998, 43.

[13] Similarly, Kosovo’s Albanian terrorists erected after the Kosovo War in 1998−1999 a statue devoted to Bill Clinton and renamed the main avenue in Priština by his name.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.