Views: 2122

It was in 2015 hundred years anniversary of secret treaty signed between three Entente members of the U.K., France and the Russian Empire on the one hand, and Italy on the other, in London on April 26th, 1915 nine months after the break up the Great War of 1914−1918.[1]

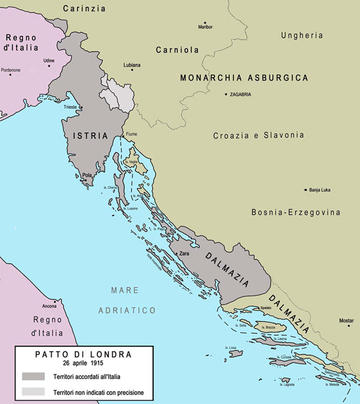

In a political-military effort to involve Italy in the war on their own side against the Central Powers members of Germany and Austria-Hungary within a month, these three Entente block members confirmed the Italian possession of the ex-Ottoman province of Libya (acquired by Italy in 1912) and the Dodecanese islands in the Mediterranean Sea and also promised the Italian occupation and annexation of Italia Irredenta territories: the South Tirol, Trentino, the Istrian Peninsula, Gorizia, Postojna, Gradisca, the North Dalmatia with the cities of Zadar and Šibenik, most of the Adriatic islands and the city of Trieste with its hinterland.[2] Italy would also gain certain Ottoman territories in Asia Minor and Albania’s city of Valona and Saseno island in the case of the victory of the Entente Powers. It is obvious that the treaty was to a full extent against the post-war territorial interests of the Central Powers, i.e., of Austria-Hungary.

Italy entered the Great War on May 24th, 1915, but the opening of a southern front on the border between Italy and Austria-Hungary failed to change the balance of the war decisively. The fact is that after the November 1917 Russian Bolshevik Revolution[3] the German supported and financed Bolsheviks refuted all treaties concluded by the previous legal Imperial Russian administration and therefore did not recognize the validity of the 1915 London Treaty under the official explanation that it as a secret agreement can not be verified by the new people’s government of the Bolshevik (anti)Russia. However, the real reason for such a policy was that a new Bolshevik government in Russia, led by a Jew V. I. Lenin,[4] was a German marionette regime (as a biggest diplomatic victory of the Central Powers during the Great War) and therefore was protecting the interests of the Central Powers member states. As a result of the German-Bolshevik collaboration, a new (anti)Russian government of Bolsheviks signs with the Central Powers a Brest-Litovsk Treaty on March 3rd, 1918 that was the first peace treaty of WWI.[5] In return for peace and the Bolshevisation of Russia, Lenin’s government ceded Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, West Belarus, Poland, Ukraine, and parts of the Caucasus. Russia thus lost almost half of its European land possessions with 75% of its heavy industries with obligations to pay 6 billion gold marks in reparations to the Central Powers but the peace gave an opportunity to the Bolsheviks to consolidate their power in the civil war against their “white” opponents.[6] That was the biggest victory of the Central Powers during the Great War – a victory which could annul the 1915 London Treaty and the 1916 treaty between the Entente and Romania. However, the 1918 Brest-Litovsk Treaty was annulled by the victorious Entente Powers on November 11th, 1918, after the German defeat. Nevertheless, by the Bolsheviks ruled Russia could only manage to reclaim Ukraine and its pre-war Asian territories after the Russian Civil War of 1917−1921 that followed the October Revolution.

As the 1917 London Treaty was a flagrant violation of the U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s designs for the re-arrangement of post-war Europe,[7] it received not full regard at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, where Italy was awarded much, though not all, of Italia Irredenta.[8] The Italian outrage against the violation of the legally valid 1915 London Treaty gave a direct stimulus to the populist irredentist groups on the Italian political scene among all the most important and powerful those led by Gabrielle D’Annunzio and Benito Mussolini. A mass Fascist movement in Italy was born in the area of Trieste on the border with a new state of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes after WWI as a patriotic protest against a brutal violation of the full implementation of the London Treaty. It is true that the main points of the treaty have been realized after 1919 but not in full as it was agreed and signed between the Entente Powers and Italy. Immediately after the Paris Peace Conference, Rome was even ready to send its military to occupy the Yugoslav lands not given to Italy according to the London Treaty but only due to the U.S. diplomacy and direct military threat to Italy by the U.S. navy located in the Adriatic Sea Rome finally left this issue unsolved till the WWII.

The main territorial gain for Rome after the war according to the 1915 London Treaty was surely the province of the South Tirol or Alto Adige, today an autonomous German-speaking region in North Italy but before 1918 a historic part of Austria and the Habsburg Monarchy (Austria-Hungary from 1867). Tirol became divided between Italy and the Republic of Austria after the WWI into the north (Austrian) and south (Italian) parts according to the final Peace Treaty of St Germain (September 10th, 1919) signed in the Parisian suburb of St Germain-en-Laye between the Entente Powers and their allied states and a new state of Austria (the German-speaking part of the former Austria-Hungary) within the framework of the Paris Peace Conferences. According to the St Germain Peace Treaty, Austria was forced to accept the break up of the Austria-Hungary Monarchy, creation of two new states of Czechoslovakia and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from January 6th, 1929) but also an enlargement of the Kingdom of Romania (a Greater Romania) and Italy at the expense of the former Habsburg state’s lands. Italy, according to the 1915 London Treaty, received Trentino, Alto Adige, Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, part of Dalmatia, Fiume (Rijeka), and a main part of the Adriatic islands. The Yugoslavs got from the Habsburg Monarchy the present-day Slovenia, Croatia, Slavonia, part of Dalmatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Vojvodina (South Hungary), Baranja, and Srem while Romania received Transylvania, Bukovina, and the East Banat. In addition, Austrian Galicia went to Poland. Austria (Österreich) thus became a landlocked Alpine country in territorial disputes with all her neighbors except with Switzerland.

The St Germain Treaty was signed with the greatest reluctance by all representatives of new Austria and the most disputed territory became the South Tirol (Alto Adige) with a German-speaking majority. The process of Italianization of Alto Adige was introduced and programmed by a new Italian fascist government after 1922 of Benito Mussolini. The purpose was to destroy the regional German distinctiveness in order to closer include the South Tirol into the Italian national state. However, the main reason why Italy required Alto Adige from Austria-Hungary and got it by the signature of the 1915 London Treaty was to control strategically extremely important Brenner Pass as a passage through the Alps. In the other words, Italy required the region of South Tirol by using the strategic claims but not ethnic or historic as was the case with Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, Fiume (Rijeka), Dalmatia, and the Adriatic islands.

Two the most important immediate consequences of the fact that the 1915 London Treaty was not implemented in full after WWI have been the D’Annunziada by Gabriele D’Annunzio and the rising of the Fascist movement led by Benito Mussolini.

Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863−1938) was a well-known Italian writer and nationalistic political adventurer – a kind of Mussolini before Mussolini.[9] He started his active political life in 1897 when entered the Chamber of Deputies where he was supporting and the extreme right and the extreme left politicians. For the reason of personal debts, he left his motherland Italy in 1910 but returned back as a nationalistic patriot in order to serve in WWI, where became a war hero with a distinguished record in the Italian army, especially in the air force. He was one of the most ardent Italian patriots to fight for the realization of all points of the 1915 London Treaty especially regarding the city of Fiume (Rijeka) on the Yugoslav littoral populated at that time by the majority of Italians. Appalled by the Italian failure to secure this disputed city between Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes he simply staged a coup and occupied the city with the Italian volunteers (a la Garibaldi) for the sake to include Fiume into a Greater Italy. After the D’Annunziada he established in Fiume a sort of authoritarian right-wing regime later followed by Mussolini in Italy. Nevertheless, D’Annunzio succeeded to defy the Italian government even for sixteen months, until he became eventually forced to leave Fiume in January 1921 but mainly due to him and his adventure Italy finally received Fiume according to the Rome Agreements signed with the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on January 27th, 1924[10] and crucially supported by the Vatican.[11]

The East Adriatic territories afforded to the Kingdom of Italy according to the London Treaty of April 26th, 1915

The East Adriatic territories afforded to the Kingdom of Italy according to the London Treaty of April 26th, 1915

Benito Mussolini (1883−1945) was a leader of the Fascist movement of Italy, son of a socialist and anticlerical blacksmith, largely self-educated, primary school teacher and journalist who organized his movement immediately after the WWI as a direct populist protest against the Entente’s policy of not respecting in full the Italian historic and nationality rights recognized by the 1915 London Treaty.[12] The first massive-protest manifestations by Mussolini’s fascists took place around the border with a new Yugoslav state which was protecting Croat and Slovenian national pretensions on the disputed territories with Italy in Dalmatia. If the 1919 Versailles Treaty was “a bone in the throat” of Adolf Hitler, then for sure the post-war incomplete realization of the 1915 London Treaty played the same irritating role in the throats of both D’Annunzio and Mussolini. Mussolini like D’Annunzio broke with the Italian socialists over WWI and went passionately to it supporting the Italian national-territorial claims which were guaranteed by the 1915 London Treaty. An idea of united ethnolinguistic Italy became one of the crucial reasons for Mussolini to establish on March 23rd, 1919 the Fascist movement that was originally under the name of the Fasci di Combattimento, which he sought to develop into an anti-socialist and anti-capitalist mass movement for the realization of the Italian ethnohistorical rights on the opposite side of the Adriatic Sea. From the mid-1920 Mussolini’s nationalism became more aggressive, with his emphasis on the Mare Nostrum policy in which the Adriatic Sea has to be converted into the Italian Lake as it was during the existence of the Republic of Venice. Here, we have to remind ourselves that Venice ruled Dalmatia, the Adriatic islands, and Istria according to the legal contracts from 1000 to 1797 that became a crucial basis for the Italian legitimate claims on this province during WWI and after as a last phase of the Italian Risorgimento.[13]

The fact is that the only reason for Rome to join the WWI on the Entente side in 1915 regardless of the fact that Italy was a member of the Central Powers from 1882 was to finish the process of the Italian national-state unification which started in 1861 with a proclamation of (not fully united) the Kingdom of Italy.[14] First Italy’s diplomatic anti-Central Powers move for the sake of realization of the Risorgimento policy at the expense of the Dual Monarchy was to reach an agreement with Russia in October 1909 after the 1908−1909 Annexation Crises when Austria-Hungary annexed the province of Bosnia-Herzegovina (on October 6−7th, 1908) breaking the 1878 Berlin Congress Treaty’s decisions.[15] According to this Italian-Russian agreement, as an introduction to the final change of the political-military side of Italy in April 1915, these two states will not tolerate any more additional territorial changes at the Balkans – an agreement directly pointed against Austria-Hungary.[16] For that reason, for instance, Italy disagreed on Vienna-Budapest intentions to attack Serbia in the spring of 1913[17] during the Balkan Wars[18] what also very much contributed to Italy’s alienation from the Central Powers.

Italy realized into practice a full implementation of the London Treaty in 1941 after the Axis Powers’ war against the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April and her occupation and territorial division by Germany, Italy, Bulgaria, and Hungary alongside with creation of a Greater Albania and (Greater) the Independent State of Croatia. However, after the capitulation of Italy on September 8th, 1943 all Italian possessions at the Yugoslav side of the Adriatic Sea (except Zarra) became included in the Independent State of Croatia, now supported only by Berlin.[19] What happened after the Italian capitulation is a real masterpiece of Croat diplomacy. The British policy of Winston Churchill, supporting both Croat nationalistic movements in Yugoslavia – a fascist creation of the Independent State of Croatia and the communist-partisan movement of Croat-Slovenian Josip Broz Tito, from the end of 1943 bombed the Italian-populated city of Zara (Zadar) which at that time had around 20,000 inhabitants, in order to transform it into the “empty space” for the sake to annex the city into the post-WWII Greater Croatia within Tito’s Yugoslavia enlarged by the Italian pre-war possessions. The destruction of Zara is comparable with the 1945 destruction of Dresden.[20]

Finally, all East Adriatic lands afforded to Italy according to the 1915 London Treaty, except the Trieste area (Zone A), became included in Croatia (except small Istrian littoral given to Slovenia) within Socialist Yugoslavia with the massive ethnic cleansing of the Italian-speaking population. Therefore, as a final result of WWII, Croatia became the only Nazi Germany ally that finished the war with an enlarged state’s territory. Present-day Croatia, alongside Albania and Kosovo, is the only almost totally ethnically cleansed and homogeneous state in Europe. Nevertheless, it is only up to Italy to decide when to start the process of reaffirmation of the 1915 London Treaty’s articles regarding its own historical and ethnic possessions at the East Adriatic.

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirovic 2016

Personal disclaimer: The author writes for this publication in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.

[1] On the WWI, see [S. F. Meaker, World War One: A Concise History. The Great War, Kindle edition, 2013; C. Falls, The First World War, Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sward Military, 2014; J. S. Levy, J. A. Vasquez (eds.), The Outbreak of the First World War: Structure, Politics, and Decision-Making, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014].

[2] М. Радојевић, Љ. Димић, Србија у Великом рату 1914−1918, Београд: СКЗ−Београдски форум за свет равноправних, 2014, 167.

[3] On the Bolshevik Revolution, see [S. Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2008; A Rabinowitch, The Bolsheviks Come to Power: The Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd, Haymarket Books, 2009; S. Engdahl, Bolshevik Revolution, Greenhaeven Press, 2013].

[4] On Lenin’s biography, see [R. Service, Lenin: A Biography, London: Pan Books, 2002; M. Black, Lenin: A Very Brief History, Kindle edition, 2013; T. Krausz, Reconstructing Lenin: An Intellectual Biography, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2015].

[5] On the 1918 Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty, see [J. W. Wheeler-Bennett, Brest-Litovsk: The Forgotten Peace. March 1918, W W North & Co Inc, 1971; Y. Felshtinsky, Lenin, Trotsky, Germany and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk: The Collapse of the World Revolution, November 1917−November 1918, Russell Enterprises, 2012].

[6] J. Anisimov, Rusijos istorija nuo Riuriko iki Putino. Žmonės. Įvykiai. Datos, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2014, 346.

[7] On this issue, see [N. G. Levin, Woodrow Wilson and the Paris Peace Conference, Health, 1972; A. Walworth, Wilson and His Peacemakers. American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, New York−London: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1986; W. Wilson, Fourteen points, Leef.com Books, 2013].

[8] On the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, see [E. M. House (ed.), What Really Happened at Paris: The Story of the Peace Conference, 1918−1919 by American Delegates, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921; M. MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World, New York: Random House, Inc., 2002].

[9] On his biography, see [L. Hughes-Hallett, Gabriele D’Annunzio: Poet, Seducer, and Preacher of War, New York: Anchor Books a Division of Random House LLC, 2013].

[10] On this issue, see more in [V. Bratulić, „Politički sporazumi Kraljevine Italije i Kraljevine SHS odnosno Jugoslavije nakon Rapala“, Jadranski zbornik, 6, 1966; B. Krizman, Vanjska politika Jugoslavenske države 1918−1941, Zagreb, 1975].

[11] The Vatican was in essence against the dissolution of the Roman Catholic Austria-Hungary and the creation of the Orthodox-dominated Yugoslavia [B. Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988. Prva knjiga. Kraljevina Jugoslavija 1914−1941, Beograd: NOLIT, 1988, 25] and for that reason supported any territorial claim of Roman Catholic Italy against all kinds of the Yugoslav states.

[12] On Benito Mussolini’s biography, see [J. Ridley, Mussolini. A Biography, New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000; R. J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini, New Edition, London: Bloomsbury, 2002; Ch. Hibbert, Mussolini. The Rise and Fall of Il Duce, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008].

[13] J. M. Roberts, The New Penguin History of the World. Fourth edition, London−New York: Allen Lane an imprint of the Penguin Press, 2002, 892

[14] On the Italian Risorgimento, see [D. Beales, E. F. Biagini, The Risorgimento and the Unification of Italy, Second edition, New York: Routledge, 2002; F. C. Schneid, The Second War of Italian Unification 1859−1861, Osprey Publishing, 2014; G. Darby, The Unification of Italy, Second Edition with Additional Documentary Material, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014].

[15] В. Ћоровић, Историја Срба, Београд: БИГЗ, 1993, 697−702.

[16] М. Радојевић, Љ. Димић, Србија у Великом рату 1914−1918, Београд: СКЗ−Београдски форум за свет равноправних, 2014, 61.

[17] Ј. М. Јовановић, Стварање заједничке државе Срба, Хрвата и Словенаца, књига 1, Београд, 14.

[18] On the Balkan Wars, 1912−1913, see [J. G. Schurman, The Balkan Wars: 1912−1913, Third Edition, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015].

[19] S. Srkulj, J. Lučić, Hrvatska povijest u dvadeset pet karata. Prošireno i dopunjeno izdanje, Zagreb: Hrvatski informativni centar, 1996, 105−107.

[20] М. Самарџић, Крвави Васкрс 1944. Савазничка бомбардовања српских градова, Београд: UNA Press, 2011, 99.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS