Views: 1265

Preface

The article deals with relations between on the one hand the supporters of pan-European identity, which has to take the place of the particular national ones, and on the other hand the proponents of maintaining specific national identities as the top priority within the European Union (the EU). Certainly, the European Union continues to expand its borders, individual national currencies are becoming unified into the common EU currency – Euro (€), and the political and economic climates are gravitating towards pan-continental unification. However, what does this unification process mean in terms of identity? The crucial question is: Will the success of the EU rest solely in economic and political interdependence or will a strong pan-European identity emerge in a fashion similar to what we see in the United States, Australia, France, New Zealand, etc.? This article will try to identify already existing views and models in regard to the creation of pan-European identity before addressing additional factors which have to be taken into consideration as well as.

Introduction

The EU is today a composition of 28 Member States across the European continent with a perspective to include more Member States from the East in the future within the common policy of the so-called Eastward Enlargement. Currently, the candidate states are Montenegro, Turkey, Serbia (without Kosovo), and Republic of North Macedonia (ex-the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). On May 7th, 2009 started the initiative given by Poland of closer relations and cooperation between the EU and several post-Soviet republics: Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova. The initiative became a program of the Eastern Partnership with the final task to attract those countries to finally become the Member States of the EU. It is obvious that the EU has a great chance to become more than present-day 28 member states (or with Brexit 27), but the crucial question of the Eastward Enlargement’s policy still left unsolved: the question of internal coherence, stability, functionality and above all solidarity among all so different and historically antagonistic member states and their national and ethnolinguistic groups.[1]

Nevertheless, the EU eastward enlargement with the possible inclusion of Turkey and former Socialist states of ex-Yugoslavia and ex-USSR is for sure the biggest challenge to the EU’s institutional, political and financial construction from the very beginning of the present-day EU in 1951 (the European Coal and Steel Community). But moreover, it is “a major challenge for our understanding of the meaning of Europe as a geographical, social and cultural space. It is also a question of the identity of Europe as one shaped by social or systemic integration” [18]. In other words, if the EU’s political construction is intended to survive for a longer time we strongly believe that it would be necessary to construct common pan-European identity which would be accepted by a strong majority of the EU’s citizens. Otherwise, the EU will degrade itself to the integration level of the EFTA: just a customs union and common market for the goods, labor force, and capital.[2]

European identity is more diluted than the concept of identity normally suggests, but it is nevertheless a new reality that has normative significance. An important aspect of social and political change over the past 25 years has been the Europeanization of identities. This can be seen in at least two ways:

- There is the increasing importance of European identities in the sense of identities that involve some degree of reference or orientation to Europe.

- European identity can be seen, not as an identity that is outside or anti-national, but as an internal transformation of national identities.

In its most explicit form, Europeanization is conceptualized as the process of downloading the EU’s directives, regulations, and institutional structures to the domestic level. However, this conceptualization of Europeanization has been extended in the literature in terms of uploading to the EU, shared beliefs, informal and formal rules, discourse, identities and vertical and horizontal policy transfer. Further issues regarding conceptualizations of Europeanization relate to direct and indirect impacts, diversity and uniformity and fit and misfit. There are also problems concerning the differences and similarities between Europeanization and European integration and whether the former offers anything new to the study and analysis of the EU.

It is worth to be mentioned that a governance approach to Europeanization has a lot of reasons. Definitions of governance abound. However, common in most definitions of governance is the idea that there is wide participation of public, private and voluntary actors in the policy process. The core executive approach suggests that the heart of Government should be seen not merely as the important formal institutions (government departments, the Prime Minister’s Office, the Cabinet and related committees etc.), but also the networks that surround them.

Ethnic indifference and common pan-European identity

In my strong opinion, the best model of creation of common pan-European identity is the French example-model of ethnic indifference according to which, all citizens within the state’s borders belong to the political identity of state-nation. This model presupposes the use of only one official language in the public sphere. The French model of ethnic indifference can be described as a model in which all persons who hold the citizenship of a state (regardless on ethnic or national origin, etc.) form the people of the state. Basically this model of group identity is derived from the concept of a citizenship-nation which defines the nation as its people (inhabitants) plus their citizenship. Simplified model’s formula “state-nation-language” is implied in many states across the world including, for instance, France, the United States of America, Canada, Australia, Switzerland, New Zealand, and Belgium.

The French model of ethnic indifference is built on the following five basic principles:

- It uses a state-nation model emphasizing the importance of the state over the nation.

- It creates a civic society as opposed to an ethnic society favored by the German model of ethnic difference.

- It creates a nationally-linguistic homogeneous state.

- It integrates minorities into society.

- It leads to no ethnolinguistic minorities with a consequence to assimilate them.

However, at first glance, the French model of ethnic indifference seems an ideal way to establish common pan-European identity. Nevertheless, when the model is deeply analyzed there are fundamental issues which must be ironed out. The fact is that the EU is a collaboration of (up to now) 28 historically unique parts. Thirteen of them are newly accepted members (in 2004, 2007 and 2013) from former Eastern Europe with a highly expressed ethnolinguistic nationalism for the sake to protect their particular ethnolinguistic identity.[3] We have to remind ourselves that even one-party dictatorial regimes of the former Soviet Union or Yugoslavia could not succeed to introduce widely accepted supranational identity of “homo Sovieticus”, “homo Yugoslavicus” respectively, among their citizens.[4]

Here the crucial points are that:

- It is impossible to “assimilate” the ethnolinguistic cultures in the case of the EU (or the United States of Europe – the USE), as the way of the full integration according to the French model of state-nation formation (after 1795) that is presented above.

- It is not necessary to do any kind of cultural assimilation.

In my belief, therefore, the successful common sense of solidarity can be based only on the common sense of a pan-European identity which has to be developed within the framework of a common EU’s citizenship. Additional problem is that the EU is in a unique world-wide situation as it is still multiethnic experiment and not truly unified as a “state” in real meaning of the term although in many ways it plays the role of it.[5]

The French model is, anyway, a great starting point, but modifications are necessary to make it applicable to the situation of the EU or in the future in the USE. However, contrary to the French model of ethnic indifference, the German model of ethnic difference or “Kulturnation” model based on the “language-nation-state” formula is in my opinion not practicable and applicable for the creation of common pan-European identity and a common solidarity based on it for the sake of better and stronger internal EU’s integration as it fosters ethnolinguistic differences, ethnonationalism and historical particularities.[6]

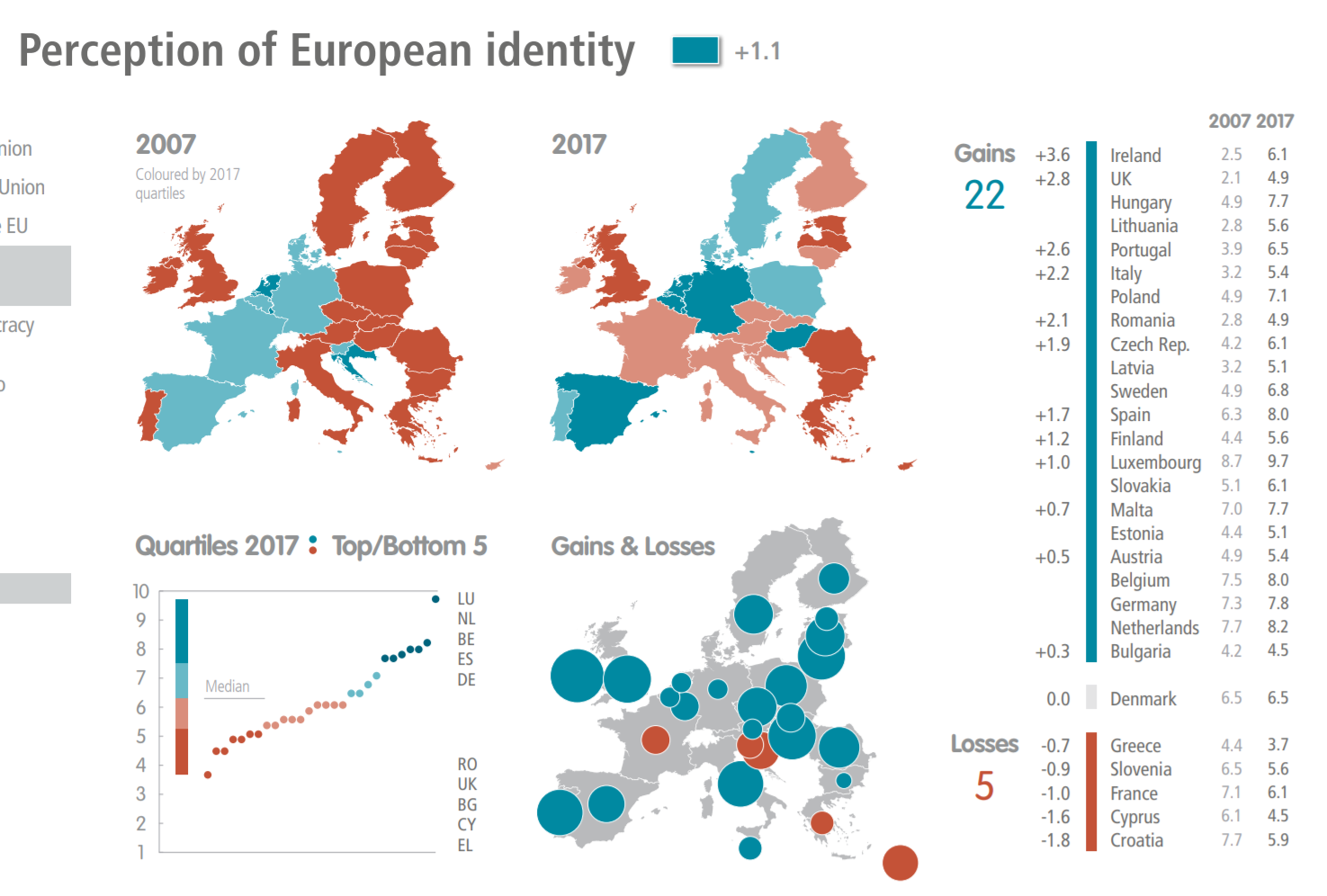

Some of the research results of the public opinion in the EU say that “according to a poll conducted by the European Commission in all 25 member states last year, more than two-thirds of respondents say they feel ‘attached’ to Europe. Fifty-seven per cent see their identity as having a ‘European dimension’ in the near future, up to five percentage points from 1999, while 41 per cent say their identity remains entirely national.”[6]. As the EU’s citizens are feeling “attached” to Europe, the question is why did it happen?

The next part of the article will try to define the concepts of common pan-European identity in order to try to give an answer to this question.

The concepts of common pan-European identity

There are many discussions on the question of how to establish common pan-European identity. I think that the starting step in this process is firstly to investigate how the EU’s citizens feel the idea of common pan-European identity. In the next paragraph, it will be present some of the relevant research results on this issue.

According to the Herald Tribune,

“most of the EU citizens who say they feel ‘European’ still rank their national identity higher than their European one, opinion polls show. But among those aged 21 to 35, almost a third says they feel more European than German, French or Italian, according to a survey by Time magazine in 2001”.

Additionally, a survey conducted by Eurobarometer found that at the end of 2004 only 47% of EU citizens saw themselves as citizens of both their country and Europe, 41% as citizens of their country only. 86 % of the interviewees felt pride in their country, while 68% were proud of being European. In general, people feel more attached to their country (92%), region (88%), city (87%) than to Europe (67%) [16]. According to Eurobarometer’s research results in 2002, for all EU15 states a fear that European integration means loss of national identity was expressed by 43% of respondents. The highest per cent was in North Ireland (62) and the lowest in Belgium (31). However, it was clear that in each of those EU15 states there were at least 31% of respondents who did not believe into a common pan-European identity [57].

The question is what causes this lack of common pan-European identity despite the expansion of the EU and a falling of the borders between the Member States? First, assuming that common pan-European identity emerges from an exchange of intercultural relations follows what it refers to as the constructivist view of Europe as space of encounters:

“as identities undergo constant change, ‘European identity’ would be encompassing multiple meanings and identifications and would be constantly redefined through relationships with others. ‘United in Diversity’ would mean the participation in collective political and cultural practices. It would be wrong and impossible to fix EU borders” [37].

The critics of this theoretical concept claim that it overestimates the ability to adapt, underestimates the need for stability and “too much diversity can eventually lead to the loss of identity, orientation and coherence, and therefore undermine democracy and established communities” [37]. Nevertheless, it is believed that any kind of successful and functional concept of common pan-European identity has to be developed within the framework of liberal democracy.[7]

With a little period gone by since the EU more than doubled in size, adding 13 new members from 2004 to 2013, it is quite difficult to claim precisely what is the future of common pan-European identity. Without any ability to conduct empirical tests the effect of Europe as space of encounters can only be discussed theoretically leading to inconclusive results. Nevertheless, I think that there is a reason for optimism. Both the EU and Europe are rapidly changing, but the question is will this change constantly redefine the multiple meanings of European identity portrayed by the view of Europe as a space of encounters?[8]

If the EU is not solely a Europe of space of encounters, then the question becomes how to define common pan-European identity? For the theory of the EU (the USE and Europe as a continent) as a space of encounters certainly has its fair share of critics allowing for alternative definitions to arise. One of the most prosperous starting points for establishing common pan-European identity is the common (unifying) culture and (positive) history throughout the Old continent.[9] The so-called “communitarians” believe in the view (concept) of Europe of culture or European family of nations. This view is defined as:

“The European identity has emerged from common movements in religion and philosophy, politics, science and the arts. Therefore, they tend to exclude Turkey from the ranks of possible future member states and argue a stronger awareness of the Christian (or Judeo-Christian) tradition. ‘United in diversity’ is taken to refer to Europe as a ‘family of nations’. On this basis, it is high time to define EU borders” [16].

There are two most important problems of this concept: 1) it excludes the inclusion of minority populations within the EU[10]; and 2) it opposes Turkey’s EU membership.[11] The fact is that such culture-nationalistic approach is usually the main source of conflict within the EU. Furthermore, defining common pan-European identity as Europe of culture will undoubtedly bring forth further tensions with the minority groups throughout the EU (or in the future the USE). For instance, in 2004, tensions flared in the Netherlands after filmmaker Theo van Gogh was brutally murdered by a citizen of Moroccan descent in response to van Gogh’s controversial film about the Islamic culture [17]. In response, the protestors took to the streets of Amsterdam banging pots and pans as an expression of freedom of speech. Several mosques were also burnt throughout the country by the Dutch extremists (or patriots?).

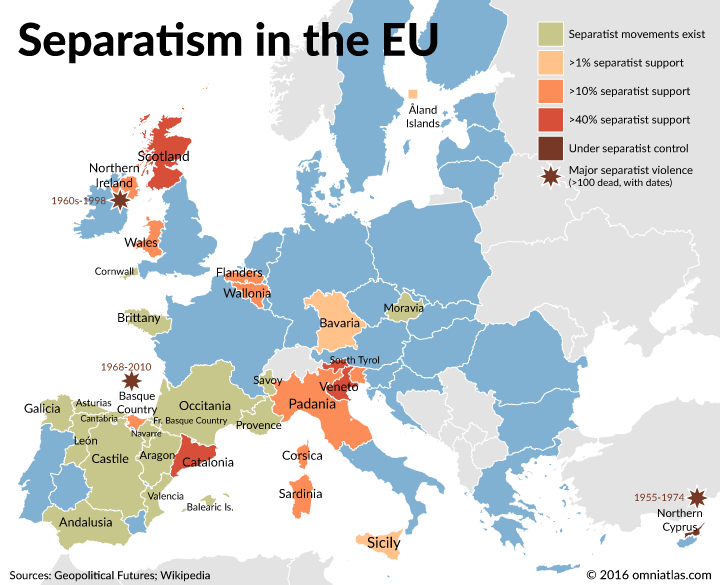

Further, in Germany, the gastarbeiter (“guest worker”) question is a highly contested issue during several last decades. The situation revolves around a large portion of people who are moving to Germany from the mid-1960’s onwards in order to fill vacant positions and help the economy to grow. However, the original idea was that they would go back to their native countries after Germany had achieved her economic success. However, most gastarbeiters decided to stay and many had children who were born and raised in Germany.[12] In general, it is essential for the European well-being to incorporate its national minorities; therefore, a view of common pan-European identity as a Europe of culture seems to be a radical and very dangerous definition, which could certainly backfire causing immense difficulties throughout the EU. In the other words, it is highly advisable to search for a definition that encompasses Europe as a whole without excluding the beliefs, customs, and history of both the national minorities (autochthonous or not) and the stateless nations in Europe.[13]

The third applicable concept can be Europe of citizens or Constitutional patriotism.[14] The main attributes of this concept are:

“[Establishing a] common political culture, or civic identity, based on universal principles of democracy, human rights, the rule of law etc. expressed in the framework of a common public sphere and political participation (or ‘constitutional patriotism’, a term coined by the German scholar Jürgen Habermas). They believe that cultural identities, religious beliefs etc. should be confined to the private sphere. For them, European identity will emerge from common political and civic practices, civil society organizations and strong EU institutions. ‘United in diversity’, according to this view, means that the citizens share the same political and civic values, while at the same time adhering to different cultural practices. The limits of the community should be a question of politics, not culture” [16].

Surely, this view calls for an assimilation of local patriotism and identities which is now reserved for the regional and private spheres, but on the general level of the whole EU only common pan-European patriotism and identity have to be on agenda. However, the critics of the concept of Europe of citizens or Constitutional patriotism state that this approach is too artificial in distinguishing the private and public, as well as subjective and universal spheres of life. These critics also claim that the national-cultural differences by this approach are ignored, but the feelings of solidarity can only occur from the cultural feelings of belonging together [25]. It means that the common solidarity feeling has to be established on the entire sum of particular national-cultural reciprocity sympathies. Otherwise, it will not function properly and for a longer period of time.

However, now the practical question is: Can common citizenship solidarity replace in the real life of the EU’s citizens historically antagonistic cultures based on different confessional denominations (Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Islam, Orthodoxy, and Judaism)? As an answer, a proposal from the EU’s Commission in Brussels came: it can if we will teach at the schools only positive historical experiences of the relations between the EU’s nations.[15] In spite of this, such approach of building solidarity effects within the EU will surely be labelled by the historians as something like “genocide against the science” or the “politics of washing brains” so experienced in all kinds of totalitarian regimes. Finally, the view of Europe of citizens or Constitutional patriotism took a major setback in late May and early June 2005, when the French and Dutch electoral bodies voted a resounding “No” on a referendum to ratify the proposed EU’s Constitution. We have to remember that according to Article IV, section 447 of the proposed EU’s Constitution, the constitutional treaty is not valid unless all countries of the EU ratify it [9].

The extreme portrayal of the concept of Europe of citizens or Constitutional patriotism is what is being labelled as the “United States of Europe”, a phrase firstly coined by Winston Churchill in his address in Zürich in 1946. This theory states that the nation-states of the EU would give into the state-nation concept of the EU thus losing their sovereignty in the process. The outcome would be a result similar to the fifty states in the United States of America. In this context, the Belgian PM Guy Verhofstadt proposed the idea to have a core of federal Europe within the EU, involving those states who wished to participate. According to his idea, five policy areas should be federalized: 1) European social-economic policy; 2) technology cooperation; 3) common justice and security policy; 4) common diplomacy; and 5) common European army.[16]

Whether to be a proponent of Europe of citizens, Europe of culture or Europe as space of encounters view, one similarity that all three concepts have to share has to be, in my opinion, a consensus on preconditions necessary for the emergence of common pan-European identity. These preconditions can be in the following spheres:

- Politics: the strengthening of democratic participation at all levels and more democracy at the EU’s level in particular.

- Education and culture: strengthening of the European dimension in certain subjects (especially history), more focus on language learning, more exchanges, etc.

- Social and economic cohesion: counteracting social and economic differences.

Additional factors on the creation of common pan-European identity

The above-presented views address possible concepts which can be applied in the practice in order to establish common pan-European identity, yet it is probably difficult to choose one view over another without encompassing a kind of mixture from all of them. The existing views also neglect very important issues of additional factors which could play a crucial role in the emergence of common pan-European identity. The next paragraphs address these additional factors.

At the heart of the creation of a strong common pan-European identity is the fact that the borders within the EU have dissipated and the citizens of the EU are able to travel freely without any visa requirements regardless the fact that many of the outsiders (“foreigners”) have to pass a certain, and even very difficult, bureaucratic procedure in order to get the EU’s visa. In the other words, at the same time of lifting the wall-borders between the EU’s Member States, especially of those who signed the Schengen Agreement (June 14th, 1985) followed by the Schengen Convention (1990) which led to creation of the Schengen Area (March 26th, 1995), the EU’s wall-borders with the outside world became even stronger.[17]

Together with the Schengen Area’s policy, there are additionally very successful factors which strongly contribute to the creation of the feeling to be a “European”. For instance, the “Erasmus/Socrates” student and teaching staff exchange (mobility) program (est. 1987) has allowed for 1.2 million Europeans to study abroad within Europe [6][18] up to 2005. This unique opportunity allows students and teachers to experience life in/of another country, participating in their understanding of a common European identity. The “Erasmus/Socrates” program (“Lifelong Learning Program” from 2007) is just one element for diversification of transcontinental experience and surely a part of the EU’s policy of the European integration.[19]

A lifting of the labor restrictions within the whole EU is a very important additional factor in creating the common European identity and feelings of solidarity as a basis for the further process of (stronger) European integration under the EU’s umbrella. In this respect, for instance, the EU has passed a law after May 2004 requiring from all old Member States (EU-15) to lift their labor restrictions on the EU-8 (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Hungary) by the year 2011. Following this requirement, Sweden, Ireland, and the United Kingdom were the first to lift their labor restrictions. Finland, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece are now completely open to the EU-8 as a result of such a policy. In the beginning, Denmark allows EU-8 citizens to stay up to 6 months to search for a job if they find one they are allowed to work legally and to arrange their residence permits. For the citizens of Bulgaria and Romania (accepted in 2007 to the EU), only Sweden and Finland have completely lifted all restrictions from the very beginning, with the other Member States implementing permit schemes. Today, travelling from place to place within the EU and working in different EU’s countries has been made both easier and cheaper.[20] Budget airlines offer extremely competitive prices to destinations across the continent, while the interconnectivity of bus and rail lines offer easy access throughout Europe often at discounted prices as well. The lack of restrictions and the access to move comfortably has created a new understanding of the European unity and subsequently of common pan-European identity within the EU’s framework.[21]

If a strong common pan-European identity has to emerge, conventional wisdom will tell us that it will certainly begin with the young generations who easily adapt to the change and novelties but as well as the young generations are mostly fitted to ideological and political manipulations and propaganda influences. The possibilities to become the “European” for the youth are numerous, with the open borders within the EU, and strong cultural and educational EU’s exchange programs, such as above mentioned “Erasmus/Socrates”, etc. The fact is that the possibilities for the young Europeans today are vast compared to the past. Technological advancements, like the internet, make cross-cultural communication both easy and effective. All of these facilities are undoubtedly contributing to the process of creation of the common pan-European solidarity and identity but only within the EU’s ideological and geopolitical premises which are in many spheres Russophobic. Moreover, the interconnectivity of the national youth councils protects and aids the voice of youth throughout the EU and beyond. Many complex networks of the youth councils have emerged, including the EU Youth Forum, the Council of Europe, and the European Youth Portal. By protecting the voices of youth today, these networks are paving the way for the (Russophobic) leaders of tomorrow. Throughout the process, the interaction between the national youth councils would help to break down cultural barriers and aid in the process of common pan-European identity formation. As one of the EU’s officials said:

“They [the European youth] are not asked to give up their national or regional identity – they are asked to go beyond it, and that it what pulls them closer together. We are creating a community in which diversity is not a problem but a characteristic. It is an integral part of feeling European” [6][22]

As the EU becomes more centralized and intercultural communication has become commonplace, an established means of communication has become essential. The English language has become a global phenomenon, serving as an auxiliary language for the citizens across the globe and more importantly throughout whole Europe as a continent. The English language emerged as a world-wide language largely as a legacy of the colonial policy of the British Empire and as well as the evolution of the United States into an economic and political superpower in the 20th century [52] taking the role of a global policeman at the time of the Cold War 2.0. For these reasons, the English language has established itself as a lingua franca in international business and subsequently as de facto auxiliary language for international communication which can significantly participate in the process of the European solidarity and identity creation.[23] Despite the rise of the English language as an auxiliary and mediator language, the EU still has almost 30 official languages and therefore spends heavily on translational services. In fact, for instance, in 2005 the total amount was “€ 1123 million, which is 1% of the annual general budget of the European Union. Divided by the population of the EU, this comes to € 2.28 per person per year” [15].

However, the EU has no plans of reducing the number of official languages anytime soon and according to the official website of the EU this is justified as follows:

“In the interests of democracy and transparency it has opted to maintain the existing system. No Member State government is willing to relinquish its own language, and candidate countries want to have theirs added to the list” [15].

The EU has decided not to switch to one official language (the English?) by now because of at least two reasons:

- “It would cut off most people in the EU from an understanding of what the EU was doing. Whichever language was chosen for such a role, most EU citizens would not understand it well enough to comply with its laws or avail themselves of their rights, or be able to express themselves in it well enough to play any part in EU affairs”.

- “Of the EU languages, English is the most widely known as either the first or second language in the EU: but recent surveys show that still, fewer than half the EU population have any usable knowledge of it” [39].

However, despite the EU’s decision to keep almost 30 official languages, having a common communicator amongst everyday citizens is the essential factor for creating a common identity. Moreover, the English language is often the preferred taught language for foreign students partaking in many different “Erasmus/Socrates” exchange locations. While the EU’s statistics claim that half of the EU’s population has no usable knowledge of the English language, naturally this statistic weighs heavily towards the older population. As addressed in the previous section, the role of the youth in establishing a pan-European identity is (very) probably crucial one. With the English language (or any other) as a lingua franca, the speaking youth brake cultural barriers and this process is going to continue for sure in the future.[24] The problem, however, can rise with the Brexit as the UK is only EU’s Member State in which the English language is an official.

The role of pop-culture supported by transnational mass media is particularly important for the creation of the common European identity as practically it has a decisive effect on it.[25] In many instances, pop-culture can help to establish a common identity particularly among the younger generations. For instance, within the music industry, each year the Eurovision Song contest encapsulates the attention of millions of viewers. Regardless of the fact that many experts stress that the context of it is of (very) low quality, there are and those who are seeing the Eurovision Song as a good promoter of the pan-European identity and reciprocity[26] (followed by the promotion of anti-Christian European LGBT’s morality and values).

Development of common European sports teams is also of extreme importance for the creation of common pan-European identity and solidarity. Such steps are already done and are going to be further built-up in the future. For instance, in professional golf, there is a European team who faces an American team in the semi-annual Ryder Cup. There has been the discussion of creating a European Union Olympic team; however, a Eurobarometer survey shows that only 5% of the EU’s citizens claim that this would make them feel more European [41]. Pan-European sport competitions such as football’s (soccer) UEFA Champions League and UEFA Cup or basketball Euro League and Euro Cup can strongly contribute to the creation of the feelings to be European. However, although such competitions might help define common pan-European identity from a pop-culture sense, the events also aid to national pride as fans often take pride in supporting the teams from their country. Thus such events both aid and hurt the establishment of common pan-European identity. Furthermore, international football competitions such as UEFA’s Euro and the FIFA’s World Cup, like similar competitions in basketball and other mass popular sports, put a strong emphasis on national pride as they see individual states competing against one another for pride and glory (aside from enormous financial compensations). Such events are not necessarily detrimental to the European identity if the Europeans are not asked to give up their national or regional identity – if they are asked to go beyond it, what would probably pull them closer together. In the other words, it is suggested to be created a community in which diversity is not a problem, but a character in order that national-regional differences would become integral parts of the feelings to be European [6].

In 2005, the internet domain .eu was launched under the title Your European Identity. In order to register a .eu domain, one must be located in the EU [41]. This step indicates common gravitation towards switching to a European mentality. The success of the .eu domain system has been extremely positive. The same is expecting and from the policy of labelling the EU products as Made in European Union.

Finally, the common EU’s currency known as the Euro (€) has to play one of the real factors in making the EU’s citizens feel as the Europeans.[27] The existence of a common EU’s currency and monetary union (the EMU) means above all an acceptance to live in a common state (the USE) what is and the final political purpose of the whole process of the so-called “Europeanization” from 1951 onwards. In the other words, to accept to live in a common political unity in a form of a state with the others above all means acceptance of common reciprocity and solidarity based on a common (pan-European) identity.[28]

Identity, pan-Europa and civilizational Europe

The identities are extremely important for people. Many people use a group identity and protectiveness to bolster their self-esteem while others use a collective identity to help them in the understanding of the world.

The meaning of Europe and, therefore, of European identity is very problematic and contested but a specific pattern of historical evolution gave the continent a distinctive identity, although this common pan-European identity is in practice divided between West and East Europe. Someone can say that at the base of European civilizational identity is the notion of modernity and progress, whereby society is turned to the future development of improvements.

What is official Europe? In the Western academic literature, it is clearly pointed out that West European integration after WWII is central to the concept of Europe which can be called as “official Europe” [60]. The EU is one of the most successful (up today) supra-national institutions in European history. However, the EU’s eastward enlargement remains quite problematic or many reasons f which a common pan-European identity is only one of them. For official Europe, the definition of something to be labelled as European-ness is founded on the so-called Copenhagen criteria: democracy of Western liberal type, the rule of law, human rights, full citizenship rights for national minorities, and functioning liberal market economy. All of those criteria are, however, the product of Western liberal thought aiming to impose a Western cultural and ideological supremacy across the continent backed by the military forces of the NATO. As the geopolitical answer, Russia sought after 1991 to make the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) as a kind of counterbalance to such Western hegemonic and neocolonial designs. In practice, the eastward enlargement of both the EU and NATO is threatening to isolate Russia, although both organizations are trying to sweeten their Russophobic policies. The attempt of Brussels to create a common pan-European identity based on Western values is only one of many applied techniques to turn Central and East European nations against Russia as “non-European” and rather “Asiatic” state which is allegedly not fitting to the standards of being European.

Nevertheless, the programs for both EU’s and NATO’s eastward enlargements are the powerful geopolitical catalyst of change in Central and East Europe during the last three decades but in turn, forced an agenda of reforms and adaptation on both the enlarging institutions and concepts of identity. The EU’s eastward enlargement, in other words, challenged the Old continent to rethink what it meant to be European leaving the most East Europeans in the lurch. The eastward enlargement is very much criticized by the Western thinkers too (for instance, Garton Ash) as it changed an already well-functioning peaceful and prosperous West European community of nations [61]. For sure, the new Member States from the East (up to today 13) will take decades to be fully integrated into “Europe” and already there are clear signs that such situation reduced the appetite for further enlargement and, therefore, searching for new types of European identity.

Europe was and is divided politically but the new sources of division came into force. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that Russia, for instance, is part of at least broader concept of European civilization. Russian literature and art have surely embellished European cultural space, its music and philosophy are an indivisible part of European thinking, and the Russians are firmly part of the European history, customs, and tradition. Consequently, such cultural unity is overcoming political divisions, geographical borders, and geopolitical designs. Of all concepts of Europe and European identity, civilizational Europe is probably the weakest one measured by Brussels’ standards of European-ness. Politically speaking, after the Cold War 1.0 division of world and Old continent, the people of Europe can freely argue that all inhabitants of Europe and Europeans now. However, the political practice of Cold War 2.0 made clear that there is no unanimity over the question: Who is distinctively European in Europe? In practice, West Europe, and particularly the EU, became kind of ideal to which the biggest part of the Old continent aspires.

European integration under the umbrella of the EU is perceived by many Europeans as a potential threat to their basic (national, regional or local) identity or identities. The degree to which the EU’s citizens worry that the European integration project can bring about a loss of national identity and culture is quite high. In fact, according to many research results of the public opinion, exclusively national identity seems to vary widely across the EU. While some of those who see themselves exclusively in national terms and those who fear the loss of national identity are openly hostile to the EU, it is more generally the case that such fears translate into ambivalence toward the EU rather than outright hostility. Nevertheless, European integration is seen by many EU’s citizens as a threat to one of the key identities of the Europeans – their national identities as the final task of the European integration within the framework of the EU is, in fact, political rather than economic. Finally, the exclusiveness of identity may be more important in explaining hostility to the EU and its project of the European unification.

Final remarks

The European identity seems fit to take on a new life given the EU’s continuous expansion. The workable concept of common pan-European identity should fall within the framework set by the theory of ethnic indifference which allows citizens not to give up their national identity but to expand their identity into a pan-European one. Different proponents support different views of the European identity, be it Europe as space of encounters, Europe of culture or Europe of citizens. It is particularly important not to ostracize national minorities in the process of defining common pan-European identity.

Technically, it is suggested that for a definite common pan-European identity to emerge one must focus on the young generations. These are the generations which are willing to adapt to change and these are the generations which will carry forth the European identity followed by the EU’s (and of the NATO) ideological and geopolitical aims especially regarding Russia. Through free mobility of labor, the lack of visas, and intercultural exchange programs, the opportunities to experience another nation are immense. Communication is easier than ever with technological advancements, such as the internet, and the emergence of English as an auxiliary language has allowed citizens to clearly communicate with one another. These are the advancements which can enable common pan-European identity in the future. Shared values and common pop-culture surely help link the continent. Probably, if in the future the Europeans (of the EU) would further unite in their diversity it could be expected that clear common pan-European identity will emerge.

It is true that the EU always needed a political purpose beyond just trade. Without political purpose, the EU construction will start to fall apart [29]. To create and to maintain common pan-European identity (alongside with particular national and regional identities) is a crucial project of keeping the whole political construction of the EU (or some kind of the United States of Europe in the future) together for the very reason that without common identity there is no common solidarity and common wish to live together within the same political framework (state).

It has to be noticed that there are four existing types of states in the world in relation to the nature of their subjects:

- 1) “People-nation state” – organized on the ethnic basis of the state’s inhabitants.

- 2) “Cultural-nation state” – organized on the basis of commonly shared culture by its subjects.

- 3) “Class-nation state” – organized on the ground of the class belonging of its subjects.

- 4) “Nation of the state’s citizens” – organized politically on the normative basis of legally interpreted individual rights [38].

In this context, many researchers strongly believe that the only successful, long-standing and democratic type of the state building applied in the case of the United States of Europe is the last fourth type for the reason that only a Constitutional patriotism can be a functional framework for the creation of common pan-European identity which has to be followed by the change of the political system of the EU in order to be more compatible with the common pan-European identity.[29]

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2019

References:

- Wiener and Th. Diez, European Integration Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Akçay and B. Yilmaz, Eds., Turkey’s Accession to the European Union. Political and Economic Challenges, Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2013.

- Denitch, Ethnic Nationalism: The Tragic Death of Yugoslavia, Minneapolis-London, p. 29, 1994.

- F. Nelsen and A. Stubb, Eds., The European Union: Readings on the Theory and Practice of European Integration, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003.

- Seidlhofer, Understanding English as a Lingua Franca, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Katrin, “Quietly Sprouting: a European Identity,” in Herald Tribune, April 26th, 2005 (http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/04/26/news/enlarge2.php).

- Klopp, German Multiculturalism: Immigrant Integration and the Transformation of Citizenship, Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2002

- Barnard, EU Employment Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Christopher, “Why Did the French and Dutch Vote No?,” in The Weekly Standard, June 13th, 2005 (http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/005/690ciqgw.asp).

- MacMillan, Discourse, Identity and the Question of Turkish Accession to the EU: Through the Looking Glass, Burlington, UT: Ashgate Publishing Group, 2013.

- Hobson, „Liberal democracy and beyond: extending the sequencing debate,“ in International Political Science Review, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 441-454, 2012.

- Marsa, The Euro: The Battle for the New Global Currency, New Haven-London: Yale University Press, 2011.

- Tragaki, Empire of Song: Europe and Nation in the Eurovision Song Contest, Lanham Maryland: Rowman, 2013.

- É. Balibar, We, The People of Europe? Reflections on Transnational Citizenship, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- “Europa: Languages and Europe,” in Europa: Gateway to the European Union, January 1st, 2007 (http://europa.eu/languages/en/document/59).

- “European Values and Identity”, Com., April 19th, 2006 (http://www.euractiv.com/en/constitution/european-values-identity/article-154441).

- “Gunman Kills Dutch Film Director,” in BBC News, November 2nd, 2004 (http://news.bbc.co .uk/2/hi/europe/3974179.stm).

- Delanty, „The Making of a Post-Western Europe: A Civilizational Analysis,“ in Thesis Eleven, no. 72, pp. 8-25, 2003.

- Gürdag, Revisiting Constitutional Patriotism Beyond Constitutionalism, Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2014.

- Merdjanova, „In Search of Identity: Nationalism and Religion in Eastern Europe,“ in Religion, State & Society, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 233-262, 2000.

- Jenkins, English as a Lingua Franca in the International University. The Politics of Academic English Language Policy, London-New York: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

- McCormick and J. Olsen, The European Union: Politics and Policies, Westernview Press, 2014.

- O. Karlsson and L. Pelling, Eds., Moving Beyond Demographics: Perspectives for a Common European Migration Policy, Stockholm: FWD Reklambyrå, 2011.

- T. Checkel and P. J. Katzenstein, Eds., European Identity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 132-166, 2009.

- W. Müller, Constitutional Patriotism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- W. Unger, M. Krzyżanowski and R. Wodak, Multilingual Encounters in Europe’s Institutional Spaces, Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

- Eitel, Cultural Globalization and the Exchange Program ‚Erasmus‘: An Institutional and Cultural Homogenization?, Grin-Verlag für academische texte, 2010.

- Fricker and M. Gluhovic, Eds., Performing the ‚New‘ Europe: Identities, Feelings, and Politics in the Eurovision Song Contest, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Bialasiewicz, „The Uncertain State(s) of Europe?,“ in European Urban and Regional Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 71-82, 2008.

- Cole and Ph. Ther, „Introduction: Current Challenges of Writing European History,“ in European History Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 4, 2010.

- Berezin and M. Schain, Eds., Europe Without Borders: Remapping Territory, Citizenship, and Identity in a Transnational Age, John Hopkins University Press, 2003.

- Bodlore-Penlaez, Atlas of Stateless Nations in Europe, Y. Lolfa Cyf., 2011.

- Bogdani, Turkey and Dilema of EU Accession: When Religion Meets Politics, Library of European Studies, I. B. Tauris, 2010.

- Brüggemann and H. Schultz-Forberg, „Becoming Pan-European? Transnational Media and the European Public Sphere,“ in International Communication Gazette, vol. 71, no. 8, pp. 693-712, 2009.

- Cini and N. Pérez-Solórzano Borragan, European Union Politics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Gilbert, European Integration: A Concise History, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2012.

- Guibernau and J. Rex, Eds., The Ethnicity Reader: Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Migration, Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 43-79, 1997.

- R. Lepsius, “Nation und Nationalismus in Deutshland,” Heinrich Winkler, Ed., in Nationalismus in der Welt von Heute, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1982.

- Mauranen and E. Ranta, Eds., English as a Lingua Franca. Studies and Findings, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010.

- Fligstein, Euro-Clash: The EU, European Identity, and the Future of Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- “Pan-European Identity,” in Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pan-European_identity).

- Chin, The Guest Worker Question in Postwar Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Phillipson, English-Only Europe? Challenging Language Policy, New York: Taylor & Frances, 2004.

- Zaiotti, Cultures of Border Control: Schengen and the Evolution of European Frontiers, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2011.

- Barbour and C. Carmichael, Eds., Language and Nationalism in Europe, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- G. Ellis and L. Klusáková, Imagining Frontiers, Contesting Identities, Pisa: Plus−Pisa University Press, 2007.

- Hardy and M. Butler, European Employment Laws: A Comparative Guide, Spiramus Press, 2011.

- Hix and B. Høyland, The Political System of the European Union, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011.

- Serfaty, “Europe 2007: From Nation-States to Member States,” in The Washington Quarterly, pp. 15-29, Autumn 2000.

- Risse, A Community of Europeans? Transnational Identities and Public Spheres, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010.

- Transatlantic Summer Academy “Euro-Atlantic Relations in the 21st Century: The Challenges Ahead” (June 5−30th, 2001), organized by the University of Bonn.

- “Universal Language,” in Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_language).

- Kymlicka, Ed., The Rights of Minority Cultures, Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Arzoz, Ed., Respecting Linguistic Diversity in the European Union, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2008.

- Heywood, Politics, Third Edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, 458.

- M. Magone, Contemporary European Politics: A Comparative Introduction, London‒New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2011, 63.

- Cini, European Union Politics, Second Edition, Oxford‒New York: Oxford University Press, 2007, 384.

- Bache, S. George, Politics in the European Union, Second Edition, Oxford‒New York: Oxford University Press, 2006, 175.

- Piattoni, Ed., The European Union: Democratic Principles and Institutional Architectures in Times of Crisis, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Sakwa, A. Stevens, Contemporary Europe, Second Edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, 22.

- Prospect, July 1999, 24.

- Dinan, Ed., Encyclopedia of the European Union, London: Macmillan, 1998, 427.

- Bernard, The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms, Fifth Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, 203‒289.

[1] On the very important issue of who are the Europeans and how does this matter for politics, see in [24].

[2] The European Free Trade Area (the EFTA) was established in the early 1960s as a competing organization to the European Economic Community led by the United Kingdom, which was less ambitious than the European Economic Community that is today the EU [56]. We have to remember that the 1992 Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty) marked in practice a major step in the process of European integration within the framework of the EU. In committed most of the Member States to adopt a single currency, extent competences in a range of areas of the European Community, strengthened the real powers of the European Parliament, created a Committee of the Regions, and introduced the concept of European citizenship. The Maastricht Treaty created a three-pillar structure of the EU, consisting of the European Community’s pillar and the intergovernmental pillars of the Common Foreign and Security Policy and Justice and Home Affairs [58].

[3] The issue of the connection between nationalism and identity in East Europe, and particularly at the Balkans, is more complex if we know that the „national churches frequently sustained and protected the national identity. In international conflicts, religious differences played an important role in defence mechanisms, especially of weaker nationalities, as in the cases of Catholicism in Ireland and in Prussian Poland“ [20].

[4] For instance, according to the 1981-census in Yugoslavia, it was only 5,4% „Yugoslavs“ (1,219,000) out of 22,428,000 inhabitants of the country [3].

[5] On this problem, see in [1, 4, 22, 35]. By academic definition, “state is a political association that establishes sovereign jurisdiction within defined territorial borders, characterized by its monopoly of legitimate violence” [55].

[6] The German model makes a clear difference between ethnic majority on one hand and ethnic minorities on the other. On the question of ethnicity and nationalism, see in [37].

[7] On debates on the concept of liberal democracy, see in [11]. On the question of borders and identities, see in [46]. About democratic principles and the EU’s institutional framework, see in [59].

[8] See, for instance, on multilingual encounters in Europe in [26].

[9] On the problem of current challenges of writing European history, see in [30].

[10] On the question of forms of cultural pluralism, see in [53].

[11] On the question of Turkey’s accession to the EU and the question of identity challenge, see in [2, 10, 33].

[12] On gasterbaiter question in Germany, see in [7, 42].

[13] On Europe’s stateless nations, see in [32]. This unique atlas takes us on a panoramic tour of the stateless nations in Europe today. It maps their physical and linguistic characteristics, and graphically summarises their history, politics and present position. The Alsatians, Basques, Corsicans, Frisians, the Scots and the Welsh are all peoples who are not sovereign and are fighting for their cultural and political identity. This atlas depicts the marvellous mosaic that is Europe today and paints a picture of a future Europe of flourishing small nations.

[14] Among many concepts on the definition of the European identity, Jürgen Habermas’s understanding of the term through the concept of Constitutional patriotism is one of the most attractive. This concept was especially relevant during the drafting and discussing the possible implications of the EU’s Constitution in 2004. However, the “No” votes in referendums in France and the Netherlands in 2005 abolished for some time the possibility of a Constitution for the EU, thus changing the nature and the focus of discussions on common pan-European identity. However, the concept of Constitutional patriotism has still plenty to offer to contribute to those debates on common pan-European identity. On the post-constitutional debates, the possibility of the evolution of the concept, the new forms of interpretation of the term and its relevance to common pan-European identity, see in [19, 25].

[15] It was told during the workshop conversation in Brussels [51].

[16] More about this issue, see in [49].

[17] On this problem, see in [44].

[18] “Erasmus” (European Community Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students) program was proposed by the European Community’s (the EC) Commission in 1985 and was accepted by the EC’s Council in 1987. The European Free Trade Association’s (the EFTA) member countries became part of this program in 1991. “Socrates” program of the EU works from 1995. The task of this program is to make better EU’s policy of enlightenment. “Erasmus” program became the most important branch out of six breaches of “Socrates” program to which it is given 55% out of total “Socrates” program budget.

[19] On this issue, see in [27, 36]. “Socrates” is a program designed formally to encourage innovation and improve the quality of education through closer cooperation between educational institutions in the EU [62].

[20] On the evolution of the labor law within the EU, the distinct national and regional approaches to the question of employment and welfare, and the pressures for change within a further enlarged EU, see in [8, 47].

[21] About free movement of persons and workers in the EU, see in [63].

[22] On the European transnational identity and citizenship, see in [14, 31, 50].

[23] On the question of the English language as a modern lingua franca, see in [5, 21, 39].

[24] On the question of language and language policy of the EU and within the European continent, see in [43, 45, 54].

[25] On the role of transnational mass media for creation of the pan-European identity, see in [34].

[26] On Eurovision Song contest and European identity, see in [13, 28].

[27] On the Euro currency, see in [12].

[28] On this problem, see in [40].

[29] On the EU’s political system, see in [48]. However, the politics and policies of creation of the common pan-European identity have to take into consideration and the question of immigrants’ integration within the political framework of the EU and the USE. On perspectives for a common European migration policy, see in [23].

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS