Views: 468

On May 28, 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law. The United States government had always used treaties as a ruse to expel Native nations from their ancestral lands, but this major federal legislation was the first that, on its face, soundly rejected tribal sovereignty and Native rights.

The Indian Removal Act stated that the president could force tribes to relocate in exchange for a “grant” of western territory where white settlers did not yet live. (No matter that the western land might already be occupied by other tribes.) This became carte blanche for the U.S. government to commit ethnic cleansing.

Prior to the act’s passage, Jackson championed the idea of not only relocating Native nations, but utterly exterminating them. Nicknamed “the Indian Fighter,” Jackson led some of the bloodiest slaughters of Indigenous people in the Americas before he became president. At the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, he and his men massacred between 850-1,000 Red Sticks, insurgent Creek (Muscogee) tribesmen who carried red ceremonial war clubs. Jackson’s soldiers tallied the dead by cutting off their noses. It was also reported that they flayed flesh from the dead and used it to make bridle reins for their horses. And some 300 Creek women and children were taken prisoner. Due to Jackson’s grisly campaign, only four months later the Creeks signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson, a document that forced them to relinquish 23 million acres of their territory and waterways. But that still wasn’t enough to satisfy Jackson.

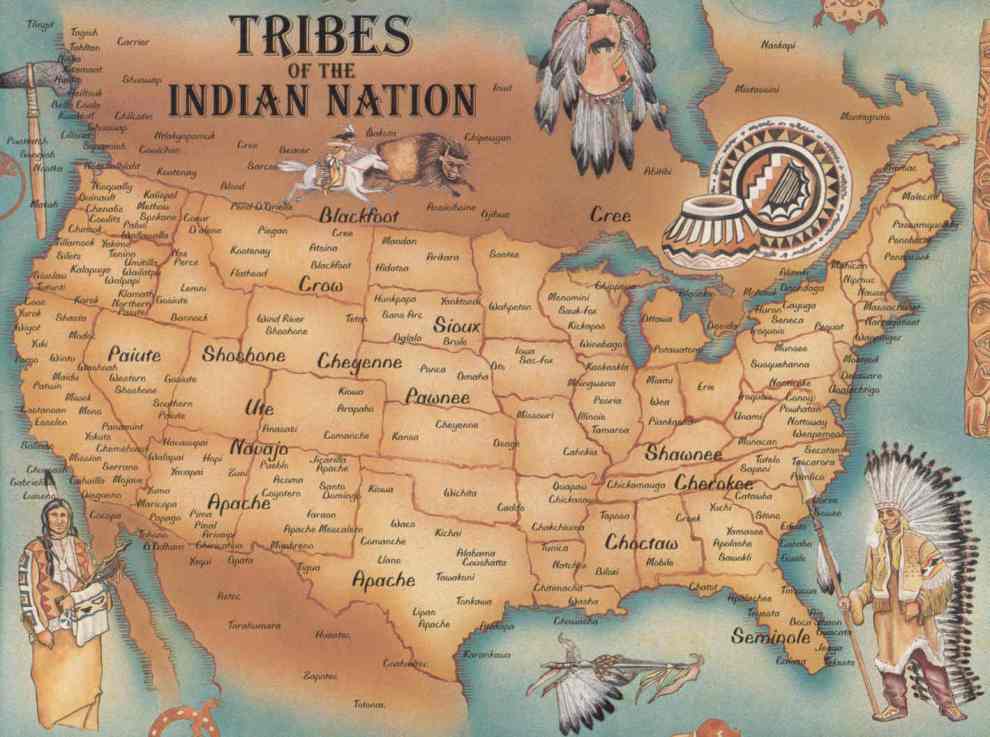

The Indian Removal Act promised that the government would negotiate with Native nations for land exchanges and that some tribes would receive payment. There was one big problem with this law, however; “the Five Civilized Tribes” that lived in the southeast — the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Cherokee, and Creek — did not want to leave. Why would they? The land that came to be called Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Tennessee had been tended and cared for by their ancestors for millennia. It was their home.

But President Jackson wasn’t concerned with respecting Native sovereignty. If tribes wouldn’t bargain with his administration and leave “the Cotton Kingdom” peacefully, he would relocate them by force.

Jackson had public support too. States were passing their own laws to steal Native lands. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the U.S. Supreme Court went so far as to uphold treaty law, affirmed tribal sovereignty, and objected to Georgia’s attempt to redraw tribal boundaries. But after the ruling, Jackson mocked the authority of the highest court in the land and let it be known that the the decision would not be enforced. The president, whose oath of office was to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States, set out to do the opposite.

Upon the signing of the Indian Removal Act, there were approximately 125,000 Indigenous people living in the southeastern United States. Over 46,000 of them were forced to abandon everything they knew and walk to Oklahoma, at times under the point of a gun.

The Choctaw (Chahta) were the first to be taken, after the U.S. Army threatened to invade their lands. In the winter of 1831, some were bound in chains and marched double file to Oklahoma “Indian Territory.” They had no food or supplies, and thousands of Choctaw men, women, and children died along the way.

In 1836, the Creeks who had survived the Red Stick slaughter were driven out of their homelands. About 15,000 Creeks began the journey; some 3,500 of them did not live to see Oklahoma.

In 1837, the Chickasaw signed the Treaty of Doaksville, but were forcibly removed thereafter, told they must resettle with the Choctaw.

A few self-appointed leaders of the Cherokee (Tsalagi) Nation said they would leave their land east of the Mississippi for $5 million, in an agreement called the Treaty of New Echota — but all Cherokee did not agree with it. Thousands of tribe members signed a petition stating that the treaty was not an act of the Cherokee Nation, including the nation’s principal chief, John Ross. Congress ignored them.

In 1838, President Martin Van Buren sent 7,000 soldiers to forcibly remove the Cherokee people from their ancestral lands. Cherokee men, women, and children were imprisoned in stockades as local white settlers looted their homes and stole their personal belongings. More than 5,000 Cherokee people died of disease, exhaustion, exposure, and starvation on the march west. This act of genocide is known as the Trail of Tears.

For seven years, the Seminole fought against their removal from present-day Florida, in the Second Seminole War. The First Seminole War had been waged between the Seminole and colonial forces led by — you guessed it — Andrew Jackson.

The federal government promised Native nations that Oklahoma Indian Territory would remain theirs forever. They broke that promise too.

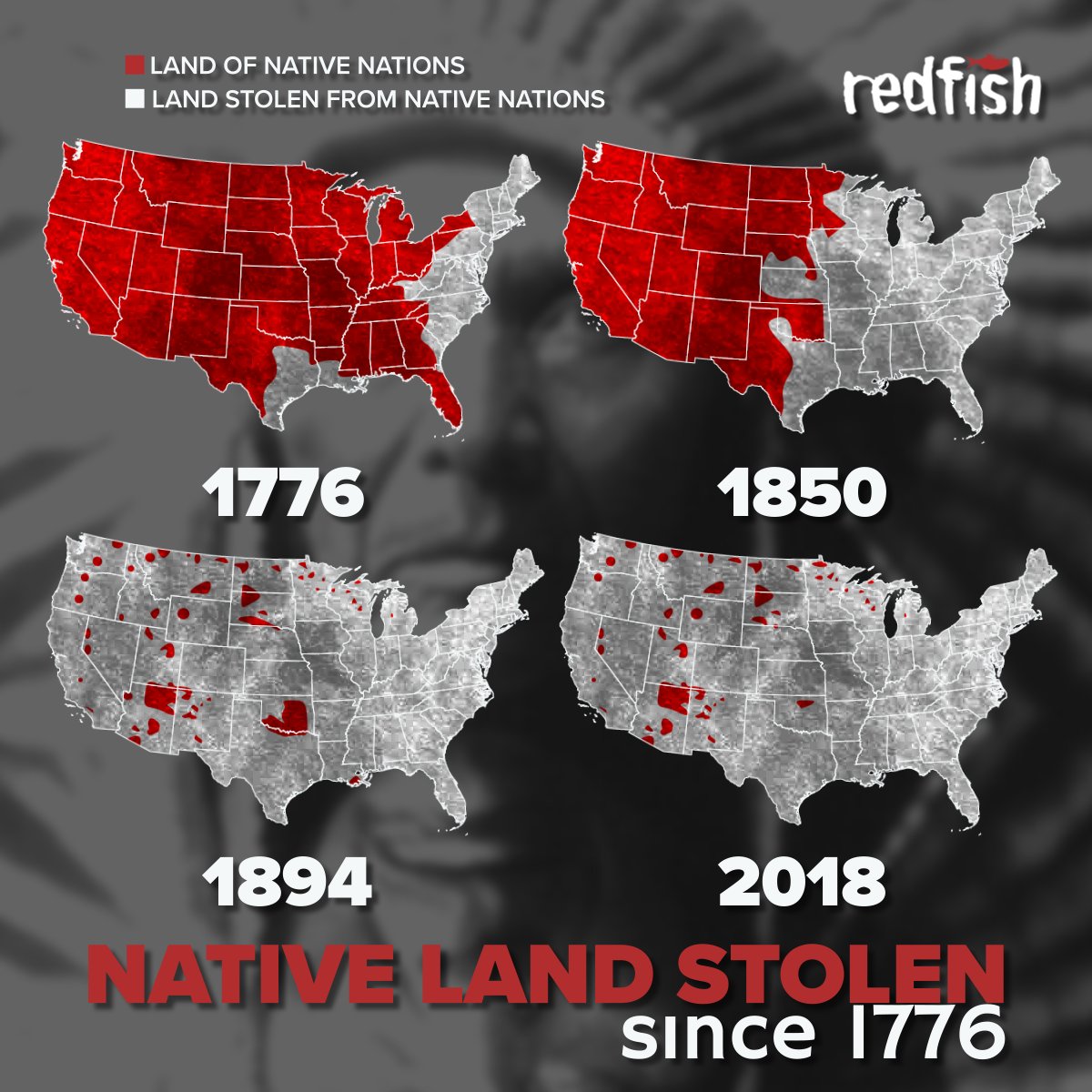

The Trail of Tears may be the best known example of the U.S. government forcibly removing Native nations from their homelands, but this pattern continued through the 19th century. In 1864, more than 8,500 Navajo (Diné) were forced to march between 250-450 miles to the Bosque Redondo Reservation, where they were held prisoner. About 200 perished from starvation and exposure on the way. In 1877, the Ponca were pushed out of their homelands and forced to relocate more than 500 miles away to Oklahoma. The Tribe had never warred with the United States, and about a third of its small population died.

The Northern Cheyenne were also forced to move from their ancestral territory in Montana to present-day Oklahoma. Conditions on the reservation were reportedly unbearable, so about 350 of them, following chiefs Little Wolf and Dull Knife, decided to leave; 149 were captured and taken to Fort Robinson in Nebraska. They were eventually taken prisoner, where they were refused food, water, and fuel for warmth. On January 9, 1879, they escaped, but 80 women and children were quickly recaptured; others ran for weeks in the bitter cold, malnourished and bone-weary. On January 22, soldiers caught up to them. Altogether, 64 Northern Cheyenne were murdered. They were just trying to go home.

My own ancestors, the Oceti Sakowin Dakota of the Great Sioux Nation, were exiled from their homelands after the Dakota War of 1862. Unilaterally, the government broke the treaties it had forged with us, stole our land, withheld our rations, and was starving us to death. When we defended our rights, the government hanged 38 of our warriors in the largest mass execution in U.S. history, imprisoned us, put a bounty on our scalps, and banished us from the state of Minnesota. In fact, there is still a law on the books that technically keeps us from owning land in that state.

These stories are horrific, and there are many more throughout history just like them, in the United States and abroad. Such is the scourge of settler colonialism — when “large numbers of settlers claim land and become the majority,” attempting “to engineer the disappearance of the original inhabitants everywhere except in nostalgia,” as historian Nancy Shoemaker put it.

The spirit of the Indian Removal Act is still alive, but now it takes the form of environmental racism, where Indigenous peoples and people of color are forced to go without potable water and to endure pollution and fossil fuel projects that encroach on their territory without their consent. Its essence is embodied in voter suppression laws that take our voices away at the ballot box, and by the government’s refusal to fulfill its treaty and trust obligations, keeping Native nations perpetually impoverished.

Settler colonialism is the opposite of democracy. Forcibly displacing Native people from their land will always be wrong, in the U.S. and all over the world.

Originally published on 2021-05-28

About the author: Ruth Hopkins, a Dakota/Lakota Sioux writer, biologist, attorney, and former tribal judge, on the legacy of the Indian Removal Act.

Source: Teen Vogue

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS