Views: 901

It is not yet clear what will replace the post-Cold War order in Europe. The major political and security institutions of this order – NATO, the EU, and the OSCE – remain, but their future roles and direction are unclear and in the process of redefinition, both from outside and from within. Major questions arise: what place do these institutions have in the emerging order, how will they relate to one another, and especially how will Russia and its neighbors, former republics of the Soviet Union, fit in the emerging order?

Thirty years have passed since the end of the Cold War. The fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of the armed standoff between East and West in Europe, and the collapse of the Soviet Union brought high hopes. The new post-Cold War political and security order envisioned a Euro-Atlantic community whole and free, from Vancouver to Vladivostok. Russia, the United States, and the major European powers would all be part of an integrated order with shared values.

Alas, this vision of an undivided Europe was never fully realized. Competing views of the architecture of the post-Cold War European security order were never reconciled. Russia was never fully integrated into western security institutions, and Moscow’s aspirations for a new pan-European security institution were never realized.

With Ukrainian President Yanukovych’s fall and flight, Russia’s seizure and annexation of Crimea, and the outbreak of war in eastern Ukraine, the post-Cold War order came to an abrupt and violent end. Although strains had been building and evident for some time, the dramatic events of 2014 marked a real break, with deep bitterness, sharp vituperation, and a new dividing line across Europe, only much farther to the East.

It is not yet clear what will replace the post-Cold War order in Europe. The major political and security institutions of this order – NATO, the EU, and the OSCE – remain, but their future roles and direction are unclear and in the process of redefinition, both from outside and from within. Major questions arise: what place do these institutions have in the emerging order, how will they relate to one another, and especially how will Russia and its neighbors, former republics of the Soviet Union, fit in the emerging order?

There are many many explanations why the post-Cold War order in Europe “did not work.” Most of these have been offered after the fact, and have the advantage of hindsight. The majority of these analyses, at least in my view, offer partial and partisan narratives, designed chiefly to assign blame on rivals or critics for the collapse of the old order. There are debates over the reason for the collapse of the post-Cold War order not only between Russian and Western leaders, but also within western political and expert circles.

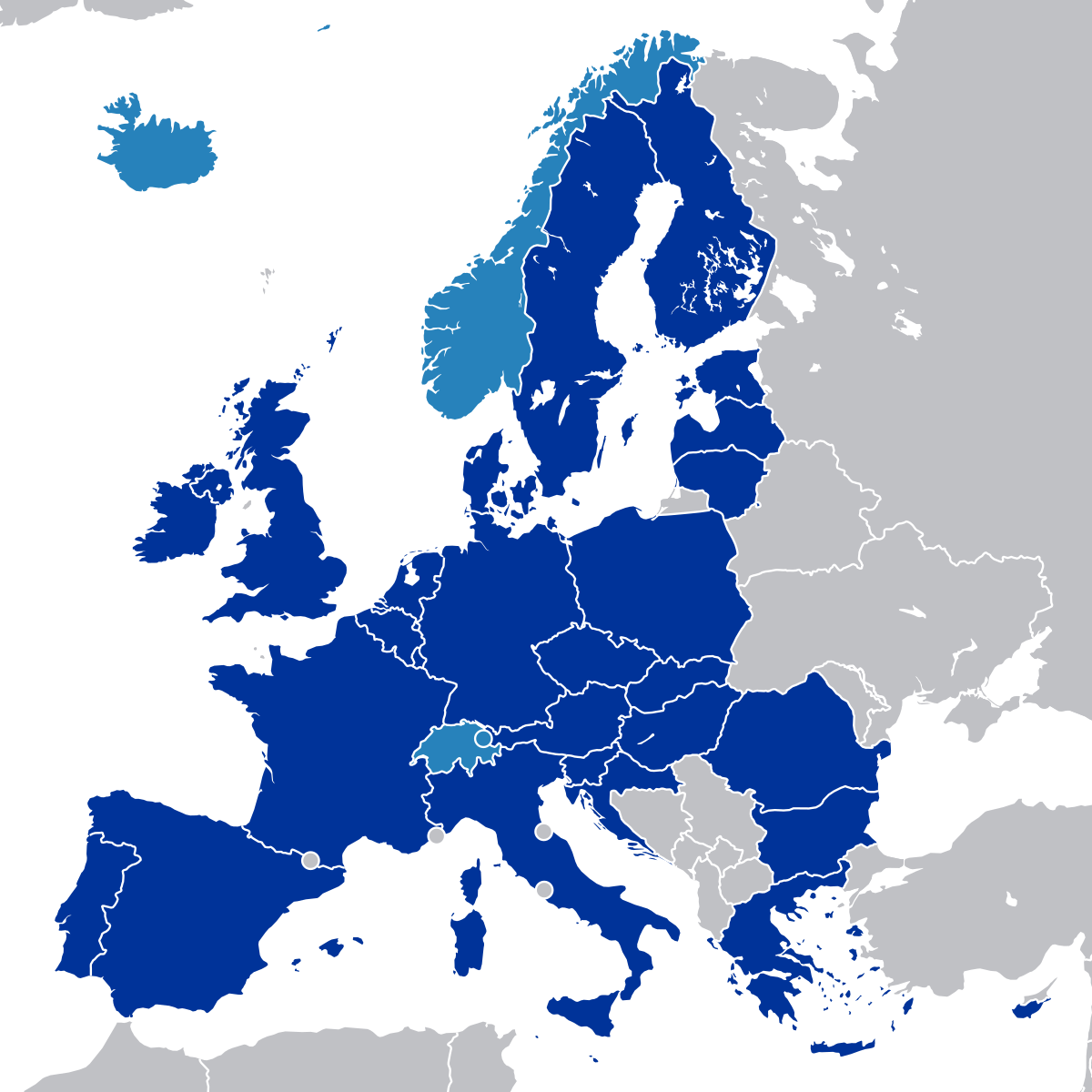

One explanation argues that the post-Cold War security architecture in Europe was quickly dominated by NATO and the EU, institutions which expanded to include most European states except Russia. In the case of the EU, membership for Russia was explicitly excluded. As for NATO, possible Russian membership was discussed at various times, both by NATO members and by Russia, but never really pursued. Many Russian politicians and analysts today complain that NATO, including NATO military facilities, has moved right up to Russia’s borders, contrary to assurances given by NATO in the early 1990s. Western leaders and analysts respond that NATO states, in particular Norway and Turkey, have always been on Russian/Soviet borders, and that military assets have been moved forward only in response to Russian military actions in Ukraine.

However, expansion to Russia’s borders and the lack of Russian membership in each institution was not the only, and arguably most important problem with EU and NATO enlargement. Moscow found it frustrating, and eventually unacceptable, that NATO and the EU took decisions on important issues which Russia considered vital for its own interests over Russia’s explicit objections. The most egregious cases of this sort are probably NATO’s decision to go to war in March 1999 against Serbia-Montenegro, and the joint NATO-EU decision in February 2008 to recognize Kosovo’s independence. In each instance Moscow complained bitterly about the NATO and EU decisions, but was unable to do anything to change them, short of war. NATO representatives maintain that Russia should have a voice but not a veto over Alliance decisions. Russians respond that without the ability to say no, their voice is muffled, if not suppressed.

Another possible, related explanation for the failure of the post-Cold War European order is that Russia, NATO, and the EU failed to use the channels and contacts they developed to conduct a real dialogue and to manage their relations successfully. The EU and Russia early on, in the 1990s, developed a four-part framework for managing their relationship. The EU-Russia dialogue dealt successfully with issues such as Russian access to the Kaliningrad exclave after accession of Poland and the Baltic states to the EU. However, after Russia’s 2008 war with Georgia, the Eastern Partnership effectively precluded Russia from multilateral discussions with the EU and involved states over regional issues. The NATO-Russia Council, established in the early 2000s, gave Russia earlier access on a more equal basis to discussion of issues with NATO member states, but no vote in actual decision-making. Nonetheless, Russian cooperation with NATO on Afghanistan and the NATO-Russia program of contacts and exercises remained quite robust well into 2013.

Yet another possible key to the collapse of the post-Cold War European order was the failure of the OSCE to develop as a true pan-European umbrella security organization. During the 1990s the OSCE deployed a large number of field missions, dealing with conflict prevention and post-conflict rehabilitation in the Balkans and the former Soviet space. The Organization also became a leader in election observation, institution building, and the rights of national minorities. However, after 2000 Moscow increasingly complained that the OSCE dealt primarily with problems in the East, that is the former Soviet area, and that western participating states refused to discuss issues of interest to Russia. Prime illustrations of such complaints might be the failure of western signatories to ratify the Adapted CFE Treaty and the increasingly moribund discussion of military security and confidence building measures, once a highlight of the OSCE’s basket one agenda.

The most severe challenges to the post-Cold War order in Europe, however, have come from disagreements over the geopolitical orientation and political-security affiliation of the states from the former Soviet Union now bordering Russia. From the time of the Soviet collapse Russia has asserted a special security interest in these states. This self-professed “sphere of privileged interest” has proved increasingly at odds with western treatment of these states as fully sovereign. As western states and institutions, such as the EU and NATO, have increased their presence and activity in these states, Russia has seen this as a challenge to its own position and interests. The collision of these conflicting views has produced war in Georgia and Ukraine.

Since 2014 the ongoing war in Donbas and resultant US and EU sanctions against Russia have deepened mutual hostility and further eroded the post-Cold War order. Russian cyber operations, such as those in the 2016 US election, and high-profile attacks on critics abroad have further damaged relations. Self-inflicted western actions such as Brexit have further shaken the post-Cold War order. Even though the Biden Administration has stressed the US dedication to European security, President Trump’s open questioning and criticism of NATO has left a significant reservoir of doubt as to the durability of this American commitment, a cornerstone of the European security order since the late 1940s.

So where does the European security order stand now? The major institutions of the post-Cold War order – NATO, the EU, and the OSCE – are still alive, but their future strength and effectiveness are quite cloudy. Russia professes an increasing turn toward Eurasia; the most recent Russian national security strategy barely mentions Europe. The US has identified China as its major rival and security challenge in the foreseeable future, and seeks to enlist Europe in this effort. The EU is still adjusting to the loss of a major member state and contributing economy, while also deliberating its future security and defense capabilities and posture, given a possible reduction in American involvement in Europe.

So, what will the emerging European security order look like? First of all, it will reflect changes in the global order, especially the rise of China. In 1989-1991 China was still a recently awakening power; it is now a global power with global reach. Second, it does not appear that new institutions or groupings are likely to emerge in Europe in the near future. In particular, no new universal European security institution or forum seems on the horizon.

Therefore, existing European institutions, groupings, platforms, and fora will need to find ways to do new things and to accomplish old tasks better. Western countries will need to conduct substantive dialogues with Russia without unduly great expectations, prioritizing goals which are truly vital and mutually achievable. Russia must find less disruptive and less coercive ways to conduct relations with its neighbors. Russia clearly has a legitimate interest in the security orientation and actions of these neighbors, but it needs to pursue these interests in less destructive, counterproductive fashion. In some cases third parties may facilitate dialogue, but they cannot impose choices on those neighbors.

A bilateral dialogue on strategic stability has begun this year between the US and Russia. This process is still very new but may hold promise of easing some tension. A renewed EU-Russia dialogue, perhaps on energy security, could also be helpful in shaping a new order. For Europe as a whole, a multilateral forum is needed to identify and begin discussion of a broad range of security issues that have emerged and accumulated as East-West relations have deteriorated over the last decade. Devoting the OSCE’s structured dialogue to deliberation on some of the more acute problems of conventional military security might be a good place to start. Actions such as these may or may not pay off, but they at least have the advantage of actively contemplating and fashioning a new, mutually acceptable, and one hopes more stable order. The alternative is to leave European security at the mercy of events, which since 2014 have led nowhere good.

Originally published on 2021-12-17

About the author: William H. Hill is Global Fellow, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Source: Russia in Global Affairs

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS