Views: 888

Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, is a host of The 20th Annual Conference of Central European Political Science Association: “Security Architecture in CEE: Present Threats and Prospects for Cooperation”. The conference place is at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University, from September 25 to 26, 2015. It is organized by the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University, and the Lithuanian Political Science Association. The conference sponsors are the Lithuanian Research Council, the Ministry of National Defence of the Republic of Lithuania, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania, and the Lithuanian Political Science Association. The number of participants with their own research papers is more than 30.

Unfortunately, our research paper proposal (abstract), submitted to the conference organizers before the deadline was rejected without a specific explanation of the reasons. Nevertheless, we are using this opportunity to participate in the conference online presenting both the abstract and the text of the research paper below:

The Post-Cold War NATO’s World Order and The Russian National Security

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

Institute of Political Sciences, Mykolas Romeris University, Vilnius, Lithuania

Email: vsotirovic@mruni.eu

Abstract

This presentation investigates the Russian foreign politics after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the time of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) World Order as a new global hegemonic power. The particular stress is put on relations between pro-Western and pro-Orthodox approaches of the Russian national interests among the Russian domestic political scene and their attitudes towards the West. The research results are based on critical analyzes of the scientific literature and prime historical sources available for the author at the moment on the topic of the paper. Special stress is put on internal Russia’s debates on the national policy after the Cold War between the pro-western and pro-traditional forces. However, the main research part of the presentation is on Russia’s relations with the West at the time of the post-Cold War NATO’s World Order in regard to the Russian national security and the foreign policy interest.

Keywords – NATO, World Order, Russia, foreign policy, international relations, global politics, Pax Americana, Atlantic Empire

The Post-Cold War NATO’s World Order and The Russian National Security

Research paper

It is a purely historical fact that “in a sharp reversal of its withdrawal from Europe after 1918, after the end of World War II Washington employed all available tools of public and cultural diplomacy to influence the hearts and minds of Europeans”[1] as a strategy of the US-led Cold War policy against the USSR,[2] and after 1991 against Russia up today. Undoubtedly, the US succeeded after 1990 to transform herself into a sole global military-political hegemonic power – an unprecedented case in world history.[3]

A Post-Cold War Global Politics

By the NATO’s globally aggressive policy and its eastward enlargement after the official end of the Cold War (1949−1989), the Russian state’s security question, reemerged as one of the major concerns in Russia.[4] However, in fact, for NATO and its motor-head in the face of the USA, the Cold War is still on the agenda of the global arena as after 1990 the NATO’s expansion and politics are directly directed primarily against Russia[5] but in perspective against China as well. Nevertheless, a fact that NATO was not dissolved after the end of the Soviet Union (regardless of all official explanations why) is the crucial argument for the opinion that the Cold War is still a reality in world politics and international relations.

It has to be noticed that the USSR was simply dissolved by one man-decision – a General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, who, concerning this matter, made a crucial deal in October 1986 with the US administration at two days bilateral meeting with the US President Ronald Reagan in Reykjavik in Iceland.[6] It is a matter of fact that the USSR was the only empire in world history that became simply dissolved by its own government as the rest of the world empires were destroyed either from the outside after the lost wars or from the inside after the bloody civil wars or revolutions.[7]

There are in our opinion three main hypothetical reasons for Gorbachev’s decision to simply dissolve the Soviet Union:

- Personal bribing of Gorbachev by the western governments (the USA and the EC).

- Gorbachev’s wish, as the first and the only ethnic Russian ruler of the USSR to prevent further economic exploitation of the Russian federal unit by the rest of the Soviet republics that was a common practice since the very beginning of the USSR after the Bolshevik (anti-Russian) Revolution and the Civil War of 1917−1921.

- Gorbachev’s determination to transform the Russian Federation, which will first get rid of the rest of the Soviet tapeworm republics, into an economically prosperous and well-to-do country by selling its own Siberia’s natural resources (gas and oil) to the West according to the global market prices.

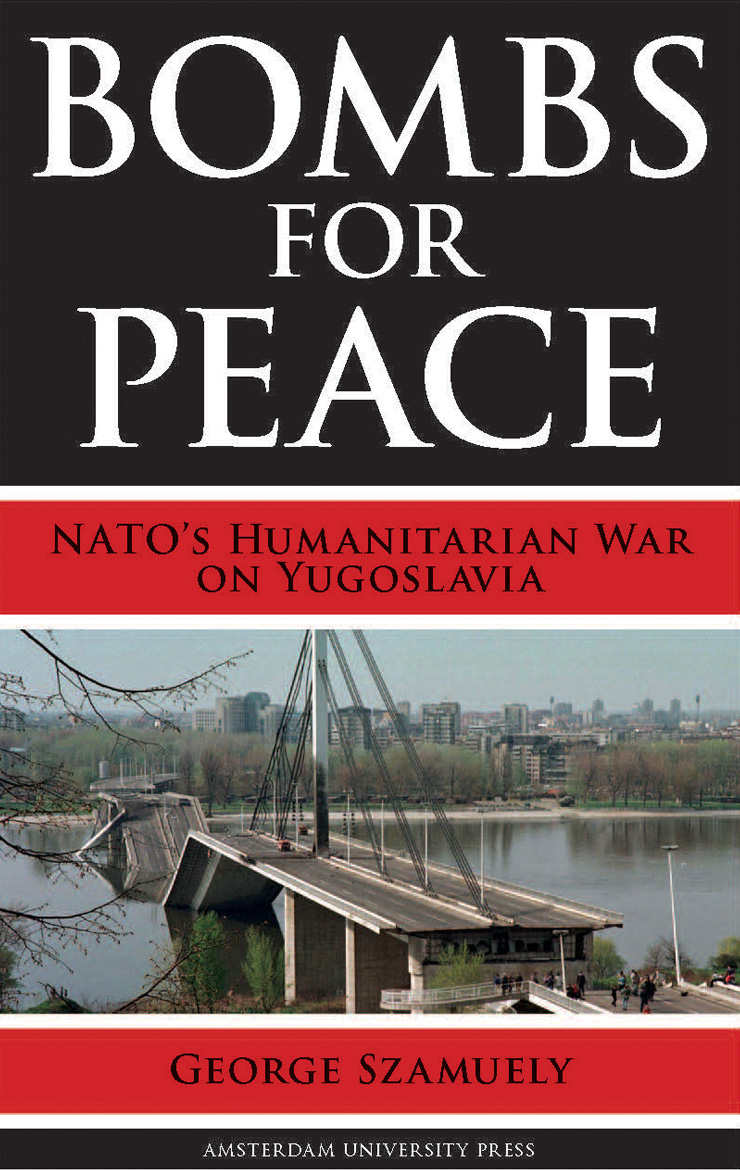

In order not to spoil very good business relations with the West the Russian foreign policy during the last 23 years, up to the 2014 Ukrainian Crisis, was totally soft and even subservient to the West to whose mercy Moscow left the rest of the world including and the ex-Soviet republics with at least 25 million of the ethnic Russian population outside the motherland. For the matter of comparison, Belgrade in 1991 also left all other Yugoslav republics to leave the federation free of charge, at least for the second hypothetical Gorbachev’s reason to dissolve the USSR, but with one crucial difference in comparison with the Russian case in the same year: the ethnic Serbs outside Serbia were not left at mercy, at least not as free of charge, to the governments of the newly (anti-Serb and neo-Nazi) proclaimed independent states emerged on the wreck of (anti-Serb and dominated by Croatia and Slovenia) ex-Yugoslavia.[8] That was the main sin by Serbia in the 1990s and for that reason, she was and still is sternly fined by the West.[9]

Russia’s Post-Cold War National Identity and State’s Security

Russia’s security and foreign policy after the dissolution of the USSR is a part of a larger debate over Russia’s “national interest” and even over the Russian new identity.[10] Since 1991, when her independence was formalized and internationally recognized, Russia has been searching for her national identity, state security, and foreign policy.

The intellectual circles in Russia have debated very much over the content of the Russian national self-identity for centuries:

- On the one hand, there were/are those who believe that the Russian culture is a part of the European culture, and as such, the Russian culture can accept some crucial (West) European values in its development, especially from the time of the emperor Peter the Great (1672−1725).[11] This group, we could call them the “Westernizers”, have never negated the existence of Russia’s specific characteristics as a Eurasian country, but have always believed that staying within the framework of the “Russian spectrum” is equivalent to national suicide (a “fear of isolation” effect).

- However, on the other hand, there are those who have tried to preserve all traditional Russian forms of living and organizing, including both political and cultural features of the Russian civilization, not denying at the same time that Russia is a European country too. This, we can name them as the “patriotic” group, or the “Patriots”, of the Slavic orientation, partly nationalistically oriented, have believed and still believes that the (West) European civilizational and cultural values can never be adjusted to the Russian national character and that it is not necessary at all for the Russian national interest (a “fear of self-destruction” effect).

A confrontation of these two groups characterizes both Russian history and present-day political and cultural development. A very similar situation is, for instance, in Serbia today as the society is sharply divided into the so-called “First” (“patriotic”) and the “Second” (“western”) Serbia supporters.

At the moment, the basic elements of the Russian national identity and state’s policy are:

- The preservation of Russia’s territorial unity.

- The protection of Russia’s interior integrity and her external (state’s) borders.

- The strengthening of Russia’s statehood particularly against the post-Cold War NATO’s Drang nach Osten policy.

- The protection of the Russian diaspora at the territory of ex-USSR in order not to experience a destiny of the Serbs outside Serbia after the violent destruction of ex-Yugoslavia by the West and their inner clients.

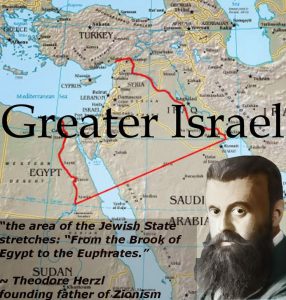

The post-Soviet Russia (the Gazprom Republic of the “Power of Siberia”) rejected, at least for the time of the 2014 Ukrainian Crisis, the most significant element in her foreign policy that has historically been from the time of the emperor Ivan the Terrible (1530−1584) the (universal) imperial code – constant expansion of its territory or, at least, the position of a power that cannot be overlooked in the settlement of strategic global matters.[12] Therefore, after the Cold War Russia accepted the US’ global role of the new world Third Rome[13], and the US as the only global hegemonic power.[14] For the matter of illustration, the US has today 900 military bases in 153 countries around the world. A (Yeltsin’s) Russian servant position to the West was clearly proved during NATO’s barbaric destruction of Serbia in 1999 – a fact which simply legitimized NATO’s policy of the US global imperialism.

The post-Soviet Russia (the Gazprom Republic of the “Power of Siberia”) rejected, at least for the time of the 2014 Ukrainian Crisis, the most significant element in her foreign policy that has historically been from the time of the emperor Ivan the Terrible (1530−1584) the (universal) imperial code – constant expansion of its territory or, at least, the position of a power that cannot be overlooked in the settlement of strategic global matters.[12] Therefore, after the Cold War Russia accepted the US’ global role of the new world Third Rome[13], and the US as the only global hegemonic power.[14] For the matter of illustration, the US has today 900 military bases in 153 countries around the world. A (Yeltsin’s) Russian servant position to the West was clearly proved during NATO’s barbaric destruction of Serbia in 1999 – a fact which simply legitimized NATO’s policy of the US global imperialism.

From a historical point of view, it can be said that the US’ imperialism started in 1812 when the US’ administration proclaimed the war on Great Britain in order to annex the British colony of Canada.[15] However, the protagonists of a “Hegemonic stability theory” argue that “a dominant military and economic power is necessary to ensure the stability and prosperity in a liberal world economy. The two key examples of such liberal hegemons are the UK during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the USA since 1945”. [16]

At the post-Cold War’s stage of Russia’s history, characterized by very harmonious (symphonic) economic and political relations with the West, at least up to the 2014 Ukrainian Crisis, especially with Germany, Russia in fact became a political colony of the West which is seen in Moscow’s eyes only as a good source for making money. The results of such kind of Russia-West relations from 1991 to 2014 were the Russian tourists all over the world, an impressive Russian state’s gold reserves (500 billion €), buying real estate properties all over the Mediterranean littoral by the Russians, huge Russian financial investments in Europe and finally, the Russian authorization of the NATO’s and the EU’s aggressive foreign policy at the Balkans, the Middle East and Central Asia.

Russia’s Post-Cold War’s Foreign Policy

Russia’s foreign policy is surely a part of her national and cultural identity as for any other state in history. From 1991 up to 2014, Moscow accepted the western academic and political propaganda as a sort of the “new facts” that:

- Russia is reportedly no longer a global super or even military power, although its considerable military potential is undeniable and very visible.

- Russia allegedly has no economic power, although it has by the very fact an enormous economic potential.

- Russia, as a consequence, cannot have any significant political influence which could affect the new international relations established after 1991, i.e. the NWO (the NATO’s World Order), or better to say – the Pax Americana.[17]

It made Russia a western well-paid client state as in essence no strategic questions can be solved without Russian permission, however for a certain sum of money or another way of compensation. For instance, the Kosovo status was solved in 2008 between Russia and the NATO/EU in exactly this way as Russia de facto agreed to Kosovo self-proclaimed independence (as the US’s client territory or colony) for in turn the western also de facto agreement to South Ossetia’s and Abkhazia’s self-proclaimed independence as in fact the Russian protected territories.[18]

It made Russia a western well-paid client state as in essence no strategic questions can be solved without Russian permission, however for a certain sum of money or another way of compensation. For instance, the Kosovo status was solved in 2008 between Russia and the NATO/EU in exactly this way as Russia de facto agreed to Kosovo self-proclaimed independence (as the US’s client territory or colony) for in turn the western also de facto agreement to South Ossetia’s and Abkhazia’s self-proclaimed independence as in fact the Russian protected territories.[18]

Since Russia formally has lost all the attributes of a super power after the dissolution of the Soviet Union (up to 2014), her political elite has in the early 1990s become oriented towards closer association with the institutional structures of the West – in accordance with her officially general drift towards liberal-democratic reform (in fact towards the tycoonization of the whole society and politics, like in all East European transitional countries). Till 1995 Russia had become a member of almost all structures of the NATO, even of the “Partnership for Peace Programme” what is telling the best about the real aims of the Gazprom Russia’s foreign policy up to 2014 when Russia finally decided to defend her own national interest, at least at the doorstep (i.e., in the Eastern Ukraine) of her own home. In May 1997 Russia signed the “NATO’s−Russia Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security”, which meant de facto that she accepted NATO as the core of the Euro-Atlantic system of security.

For the matter of comparison with the USA, in October 1962, at the height of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union came to the brink of a real nuclear war over the placement of the USSR’s missiles in the island of Cuba – a courtyard (not even a doorstep) of the USA. It was the closest moment the world ever came to unleashing WWIII.[19] In the other words, during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis the US’ Kennedy’s administration was ready to invade the independent state of Cuba (with already the US’ military base on the island) and even to go to WWIII against the USSR if necessary as Washington understood Cuba as a courtyard of the USA.

Whether or not the ruling structures in Russia had expected a more important role for their country in its relations with the new partners, since 1995 there has been certain stagnation in the relations with the West, accompanied by the insistence on the national interests of Russia. In practice, this was manifested in the attempts to strengthen the connections with the Commonwealth of the Independent States (the CIS) with which Russia had more stable and secure relations. However, the state of relations within the CIS, accompanied by a very difficult economic and politically unstable situation in some of the countries in the region, prevented any organizational or other progress in this direction. Still, the CIS has remained the primary strategic focus for Russia, especially when it comes to the insolent expansion of the NATO towards these countries (the NATO’s Drang nach Osten).

Conclusions

In the end, we will express several basic conclusions in relations to the topic of contemporary Russian relations with NATO, or better to say, to the debate of the main issue of the present-day Russian foreign policy – between the West and herself:

- The post-Soviet Russia was at least until 2014 Ukrainian Crisis politically very deeply involved in the western system of international relations and cultural values that was basically giving to Moscow a status of the western client partner on the international scene of the NATO’s World Order.

- A full victory of the Russian “Westernizers” up to 2014 allow them to further westernize Russia according to the pattern of the Emperor Peter the Great with the price of Russia’s inferiority and even servility in the international relations. For that reason, the West already succeeded (at least up to 2014) to encircle Russia with three rings of Russia’s enemies: the NATO at the West, the Muslim Central Asian states at the South, and China at the South-East.

- The West was buying Russia’s inferiority at the international scene by keeping perfect economic relations with Moscow that was allowing Russia, especially Russia’s tycoons, to become enormously reach. These harmonious West-Russia political-economic relations are going to be broken in the future only under two circumstances: I. If the Russian “Patriots” with take political power in Kremlin (after the military putsch or new revolution?), or II. If the West will introduce any kind of serious (real) economic-political sanctions against Russia (i.e. to restrict importing Russian gas and oil or to limit business operations of the Russian oil and gas companies outside Russia).

- Up to now, concerning Europe, the South-East Europe experienced a full degree of the Washington-led NATO’s World Order policy as it is totally left to the western hands by Moscow and the region is already incorporated into the NATO’s World Order as a part of the western (the NATO & the EU) post-Cold War concept of the Central and East Europe as a buffer zone against Russia.[20] Nowadays, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia is on agenda of the US’s punishment for any closer relations with Russia (the “Turkish Stream”). As it was in the case of Serbia in 1999, the US-sponsored regional Albanians (exactly from Kosovo) are the instrument of destabilization, in this case, of Macedonia as an overture to the territorial secession of the Albanian-populated West Macedonia which is going to be put, like Kosovo, under the NATO’s total occupation.

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirovic 2015

Personal disclaimer: The author writes for this publication in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.

____________________

Notes:

[1] A. Stephan (ed.), The Americanization of Europe. Culture, Diplomacy, and Anti-Americanism after 1945, New York−Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2006, 1.

[2] D. Junker (ed.), The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945−1990: A Handbook, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

[3] D. P. Forsythe, P. C. McMahon, A. Wedeman (eds.), American Foreign Policy in a Globalized World, New York−London: Routledge, 2006, 1.

[4] About history of the Cold War, see in [J. Lewis, The Cold War: A New History, New York: Penguin Books, 2005; M. V. Zubok, A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev, The University of North Carolina Press, 2007].

[5] K. W. Thompson, NATO Expansion, University Press of America, 1998.

[6] J. G. Wilson, The Triumph of Improvisation: Gorbachev’s Adaptability, Reagan’s Engagement, and the End of the Cold War, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014; K. Adelman, Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended The Cold War, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2014.

[7] About the end of the USSR, see in [S. Plokhy, The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union, New York: Basic Books, 2014].

[8] About different opinions on the nature of Yugoslavia, see in [J. B. Allcock, Explaining Yugoslavia, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000; R. Sabrina, The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918−2005, Indiana University Press, 2006].

[9] About the wars of Yugoslavia’s succession in the 1990s, see in [S. Trifunovska (ed.), Yugoslavia Through Documents: From its creation to its dissolution, Dordrecht-Boston-London: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1994; S. L. Woodward, Balkan Tragedy: Chaos and Dissolution after the Cold War, Washington, D. C.: The Brookings Institution, 1995; R. H. Ullman, (ed.), The World and Yugoslavia’s Wars, New York: A Council on Foreign Relations, 1996; D. Oven, Balkan Odyssey, London: Indigo, 1996; B. Marković, Yugoslav Crisis and the World: Chronology of Events: January 1990−October 1995, Beograd, 1996; J. Guskova, Istorija jugoslovenske krize, I−II. Beograd: Izdavački grafički atelje „M“, 2003; V. B. Sotirović, Emigration, Refugees and Ethnic Cleansing: The Death of Yugoslavia, 1991−1999, Saarbrücken: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2013].

[10] M. Laruelle (ed.), Russian Nationalism, Foreign Policy, and Identity Debates in Putin’s Russia: New Ideological Patterns After the Orange Revolution, Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag, 2012.

[11] About Peter the Great and his reforms in Russia, see in [L. Hughes, Russia in the Age of Peter the Great, New Haven−London: Yale University Press, 2000; J. Cracraft, The Revolution of Peter the Great, Cambridge, Mass.−London, England: Harvard University Press, 2003; J. Anisimov, Rusijos istorija nuo Riuriko iki Putino. Žmonės. Įvykiai. Datos, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2014, 203−229].

[12] About the idea of Holy Russia as a Third Rome, see in [M. R. Johnson, The Third Rome: Holy Russia, Tsarism and Orthodoxy, The Foundation for Economic Liberty, Inc., 2004].

[13] About the US’ post-Cold War imperialism and global hegemony, see in [G. V. Kiernan, America, The New Imperialism: From White Settlement to World Hegemony. London: Verso, 2005; J. Baron, Great Power Peace and American Primacy: The Origins and Future of a New International Order, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

[14] N. Chomsky, Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance, New York: Penguin, 2004.

[15] H. B. Parks, Istorija Sjedinjenih Američkih Država, Beograd: Izdavačka radna organizacija „Rad“, 1986, 182−202.

[16] A. Heywood, Global Politics, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 229.

[17] About the Pax Americana, see in [G. Dorrien, Imperial Designs: Neo Conservatism and The New Pax Americana, London−New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2004; A. Parchami, “The Pax Americana Debate”, Hegemonic Peace and Empire: The Pax Romana, Britanica and Americana, London−New York: Routledge, 2009; A. Roncallo, The Political Economy of Space in The Americas: The New Pax Americana, London−New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014. On the remaking of the World Order, see [S. P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilization and The Remaking of World Order, London: The Free Press, 2002; H. Kissinger, World Order, Penguin Press HC, 2014]. On the post-Cold War’s US-Russia’s relations up to the 2014 Ukrainian Crisis, see in [A. E. Stent, U.S.−Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014].

[18] About the “Kosovo precedent” and the ethnopolitical conflicts in the Caucasus, see in [A. Hehir (ed.), Kosovo, Intervention and Statebuilding: The International Community and the Transition to Independence, London-New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2010; V. B. Sotirović, “Kosovo and the Caucasus: A Domino Effect”, Српска политичка мисао (Serbian Political Thought), 41 (3), Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies, 2013, 231−241.

[19] R. F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of The Cuban Missile Crisis, W. W. Norton & Company, 1999; D. Munton, D. A. Welch, The Cuban Missile Crisis: A Concise History, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2006; M. Dobbs, One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on The Brink of Nuclear War, Borzoi Book, 2008; B. L. Pardoe, Fires of October: The Planned US Invasion of Cuba During The Missile Crisis of 1962, Fonthill Media Limited−Fonthill Media LLC, 2013.

[20] About the post-Cold War western supremacy in the global politics and international relations, see in [S. Mayer, NATO’s Post-Cold War Politics: The Changing Provision of Security, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014; K. Pijl, The Discipline of Western Supremacy: Modes of Foreign Relations and Political Economy, III, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014]. About a typical example of the western (the US’) colony in the region, Kosovo-Metohija as a part of the Pax Americana, see in [H. Hofbauer, Eksperiment Kosovo: Povratak kolonijalizma, Beograd: Albatros Plus, 2009]. On the relations between the NATO and the European Union, see in [L. Simon, Geopolitical Change, Grand Strategy and European Security: The EU−NATO Conundrum, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013]. About the history of a greater concept of the East Europe between the Germans and the Russians, see in [R. Bideleux, I. Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe. Crisis and Change, London−New York: Routledge, 1999; A. C. Janos, East Central Europe in the Modern World. The Politics of the Borderlands from Pre- to PostCommunism, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000].

Note:

Complete article published as: “The NATO’s World Order, the Balkans and the Russian National Interest”, International Journal of Politics & Law Research, Sciknow Publications Ltd., Vol. 3, № 1, 2015, New York, NY, USA, ISSN 2329-2253 (print), ISSN 2329-2245 (online), pp. 10−19 (www.sciknow.org)

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS