Views: 2058

The Yugoslav Youth Movements

The idea of the Yugoslav unification became a leading ideological force of several youth movements among all Yugoslavs either of those living in an independent Serbia and Montenegro or of those living in Austria-Hungary. Their political-ideological inspiration was a pan-Italian unification movement – Young Italy (La Giovane Italia), established by Giuseppe Mazzini in 1831 in France.

The Yugoslav youth movements flourished between 1903 and 1914 by having different regional or other names but not exclusively ethnic ones in various Yugoslav lands like Omladina (Youth), Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia), Mlada Dalmacija (Young Dalmatia), etc.[1] The Austrian general of the Slovenian ethnic origin, Oscar Potjorek, introduced a term “Jungslawen” as a common title for all of those Yugoslav youth movements. His notification was that the most significant political wish of these pro-Yugoslav movements was to establish a single South Slavic/Yugoslav state.[2]

The Yugoslav youth movements flourished between 1903 and 1914 by having different regional or other names but not exclusively ethnic ones in various Yugoslav lands like Omladina (Youth), Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia), Mlada Dalmacija (Young Dalmatia), etc.[1] The Austrian general of the Slovenian ethnic origin, Oscar Potjorek, introduced a term “Jungslawen” as a common title for all of those Yugoslav youth movements. His notification was that the most significant political wish of these pro-Yugoslav movements was to establish a single South Slavic/Yugoslav state.[2]

An appearance of Slovenski jug (Slavic South) magazine in 1903 in Belgrade marked a turning point in the process of ripening of the Yugoslav youth movements. This magazine became, in fact, in the course of time a focal meeting point of the supporters of the Yugoslav idea and the South Slavic unification. Together with a separate cultural organization under the same name, the magazine propagated an idea of a cultural integration of all Yugoslavs with the respect of their ethnic, confessional and historical differences. Actually, the movements desired a Yugoslav spiritual unification within the Yugoslav political federation as the final goal and their greatest national-political ideal.[3] The most important slogans of the magazine were: the “Union of the South Slavs” and the “Revolution at occupied lands”. The first pan-Yugoslav Youth Congress was organized in Belgrade in 1904. Three years later, also in Belgrade, the Yugoslav Revolutionary Organization was founded, which fought, according to its Statute, for the Yugoslav federal state with the autonomous provinces. Further, it was organized in Prague in 1910 the Association of the Yugoslav Clubs with the focal national aim to create a Yugoslav cultural union.[4] The Serbian and Croatian students from Vienna and Prague founded a new organization in December 1911 under the name – Serbian-Croatian National Youth. Their national idea was a Croato-Serbian; their nationality was a Serbo-Croatian.[5]

A final union of different Yugoslav youth movements into a single organization was done in the house of the Croatian writer Oscar Tartalja in Split (Dalmatia) on March 16th, 1913. In May of the same year, a pro-Yugoslav propaganda magazine of the idea of the Yugoslav unification – Ujedinjenje (Union) started to be published by the same pan-Yugoslav organization. A prime political goal of the organization was to prepare a national Yugoslav revolution that was scheduled for the year of 1917 for the very reason, in order to spoil the 50th years anniversary celebration of the Austro–Hungarian political-national settlement – Aussgleich (1867).[6]

As a matter of fact, an idea of the Yugoslav unification was accepted by the much wider South Slavic audience, especially by those pro-Yugoslavs living in Austria-Hungary, after the liberation of the South Slavic lands in the Ottoman Empire by Serbia and Montenegro in 1913 during the Balkan Wars.[7]

The Croatian Anti-Serbian National-Chauvinism and Yugoslavophobia

It is necessary to review the attitudes towards the question of the Yugoslav unification by the most influential Croatian opposition political parties represented in the Croatian-Slavonian parliament (Sabor) in Zagreb. A focal element of their national-political programs and propaganda was an extreme anti-Serbian chauvinism followed by a Yugoslavophobia for the sake of the creation of a Greater and ethnically cleaned Croatia.

The most national-chauvinistic Croatian party was the Croatian Party of Rights (Hrvatska Stranka Prava), led by an extreme Serbophobic Croatophile Ante Starčević. The main original political aim of this party was to create an independent, free, united and ethnically cleaned Greater Croatia based on self-understood ethnolinguistic and historical rights of the Croats and, therefore, including Croatia, Slavonia, Dalmatia Bosnia-Herzegovina, parts of Serbia, Montenegro, and Slovenia. This political task was radicalized when Josip Frank took over the party’s leadership. J. Frank’s political demands were to create a separate united Croatian national-administrative province within Austria-Hungary by including all South Slavic lands of Austria-Hungary into a Greater Croatia. Therefore, J. Frank’s policy of Austro-Yugoslavism was in direct service of the Austrian-Hungarian geopolitical designs in the Balkans.

Nevertheless, for the Croatian ultraright ideologists at the turn of the 20th century, Croatia should annex and incorporate into the united and single Croatian administrative province within Austria-Hungary primarily all Croatian “historical” lands (Croatia, Dalmatia, Rijeka, Istria, Dubrovnik, Slavonia, Montenegro, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Međumurje, Srem, and Bačka) followed by the rest of the lands settled by the South Slavs in the Dual Monarchy.

However, the initial slogan of the Croatian Party of Rights was “neither under Vienna or Pest, but for the free and independent Croatian state”. Any compromise with Austria-Hungary was impossible for the founder of the party (1861) – Ante Starčević, who was fighting for the creation of a Greater Croatia but outside of the Dual Monarchy or to have only the personal union with it. For him, such Greater Croatia would annex Slovenia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Međumurje, the Military Border, Rijeka, Dalmatia, Slavonia, and Istria. He was also the creator of the concept that the purest Croats live in Bosnia-Herzegovina.[8] With regard to the problem of a national identity of the Croats, in the early period of his activity A. Starčević wrote in 1867 the booklet Bi-li k Slavstvu ili ka Hrvatstvu (To the Slavdom or the Croatdom) in which he presented the opinion that the Slavic name was an artificial fabrication. According to him, the Croats could be only Croats but not either the Slavs or the Yugoslavs.[9] For him, the Yugoslav idea was only a mask for (the Orthodox) Russian Pan-Slavic policy, which was very dangerous for the (Roman Catholic) Croatian national interest. A. Starčević was not only “a father of the Croatian nation”[10] but as well and an ideological founder of an extreme Serbophobic policy, openly advocating a genocide on the Serbs within the territories of “ethnohistorical” Croatia that in reality was done during the WWII within the territory of the Independent State of Croatia.[11]

Nevertheless, in 1895 A. Starčević resigned from a party’s membership due to the internal disagreements between the party’s leaders and formed a new party – the Pure Croatian Party of Rights (Čista hrvatska stranka prava). After his death in 1896, Josip Frank took the leadership of the (new) party becoming a new champion in the spreading of Serbophobic ideology among Croats. However, in contrast to A. Starčević and being politically and financially sponsored by the Austrian authorities, J. Frank was advocating the creation of a “Greater Croatia within a Greater Austria”[12] but not as a real independent state outside the borders of Austria–Hungary, as originally Ante Starčević wanted. Therefore, any kind of the Yugoslav ideology not sponsored by the authorities of Austria-Hungary (like Austro-Yugoslavism) was unacceptable for J. Frank and his party.

It is the fact that while A. Starčević worked on the dissolution of Austria–Hungary, as the main external enemy to the realization of the Croatian national interest (the Serbs have been, according to him, the crucial internal enemy to Croatia)[13], J. Frank worked on the preservation and even strengthening of Austria-Hungary as the best protector of the Croatian national interest. The leadership of the Pure Croatian Party of Rights never adopted any positive attitude towards the South Slavic unification into the form of an independent state. Moreover, J. Frank (who was not of the Slavic origin) had strong anti-Slavic (and especially anti-Serb) attitude, and openly worked in the favour of the Rauch regime in Croatia-Slavonia (1908–1910) against the Serbs within Austria-Hungary, having his own armed paramilitary legions (the so-called “Frank’s Legions”)[14] for the terrorizing the Serbs.

J. Frank’s Pure Croatian Party of Rights became after the Sarajevo assassination (June 28th, 1914) a strongest Croatia’s Serbophobic political and paramilitary organization, calling for the war against Serbia, with the expectation to create a Greater Croatia within Austria-Hungary after the war.[15] The war against Serbia had a very practical political aim: to thwart a creation of Serbia-led Yugoslavia. In general, J. Frank’s anti-Yugoslav ideology was framed within the propaganda that the Yugoslavism was a Serbian conspiracy against Croatia and Austria-Hungary for the sake to create a Greater Serbia with the Austrian-Hungarian lands of Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina.[16]

However, on the other hand, a renewed A. Starčević’s Croatian Party of Rights, which became separated from J. Frank’s Pure Croatian Party of Rights just before the WWI, adopted during the time of the Great War of 1914–1918 a political attitude in favour of a dissolution of the Dual Monarchy and, therefore, preferred a creation of the common South Slavic state as the optimal solution to realize the Croatian national interest. During the anti-Serbian campaign in Zagreb in 1914 the Hrvat, a journal of A. Starčević’s Croatian Party of Rights, was openly on the Serbian side and interceded in the favor of the Yugoslav unification. For example, the Hrvat published several articles in which the socialists, anarchists, Hungarians, and freemasonry were accused as the organizers of the assassination in Sarajevo in 1914, but not Serbia. What concerns the Yugoslav unification, the most important article of this journal was published on July 4th, 1914 under the title “National Principle” in which the idea of the South Slavic ethnopolitical unification was supported.

Conclusions

The Serbs and the Croats have been the focal pillar of a common Yugoslav state created in 1918 and being reborn in 1945. The central part of the ideology of Yugoslavism was all the time an idea that these two nations possessed much more similarities than dissimilarities. It is true that the ethnic foundations from which the Serbs and the Croats were developed have been very similar. There were many areas of ex-Yugoslavia in which these two nations were living mixed together, and the similarity was expressed in the Serbian and Croatian standardized languages from the first half of the 19th century.

However, despite the fact that the ordinary Serbs and Croats intermarried and had many other contacts, ethnocultural differences among them all the time existed primarily due to their different confessional orientation. In essence, the Serbs and the Croats became delimited according to their religious affiliation: the Roman Catholics became the Croats and the Orthodox became the Serbs (Bosnian-Herzegovinian Muslims will today become Bosniaks). As a minority in Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia, the Orthodox Serbs felt threatened by assimilation into the Roman Catholic Croatian majority as the Roman Catholic church exactly was working on it. Therefore, the Serbs outside Serbia very much preferred a kind of Yugoslavia in which the Serbs will have a simple majority as a guarantee for the protection of the Serbian ethnic identity. The Croats, on the other hand, required from the Serbs in Dalmatia, Croatia, and Slavonia to feel united Croatia as their homeland instead to feel Serbia as mother-state.[17] For the Croats, a post-WWI Yugoslavia was just a temporal political option in order to protect their self-proclaimed historical and ethnic territories from the Italian and Hungarian policy of irredentism. Subsequently, either Serbs or Croats needed Yugoslavia just for very practical reasons but not as a consequence of some deeper ideological convictions into a common Serbo-Croat ethnic origin, reciprocity, and solidarity.

However, despite the fact that the ordinary Serbs and Croats intermarried and had many other contacts, ethnocultural differences among them all the time existed primarily due to their different confessional orientation. In essence, the Serbs and the Croats became delimited according to their religious affiliation: the Roman Catholics became the Croats and the Orthodox became the Serbs (Bosnian-Herzegovinian Muslims will today become Bosniaks). As a minority in Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia, the Orthodox Serbs felt threatened by assimilation into the Roman Catholic Croatian majority as the Roman Catholic church exactly was working on it. Therefore, the Serbs outside Serbia very much preferred a kind of Yugoslavia in which the Serbs will have a simple majority as a guarantee for the protection of the Serbian ethnic identity. The Croats, on the other hand, required from the Serbs in Dalmatia, Croatia, and Slavonia to feel united Croatia as their homeland instead to feel Serbia as mother-state.[17] For the Croats, a post-WWI Yugoslavia was just a temporal political option in order to protect their self-proclaimed historical and ethnic territories from the Italian and Hungarian policy of irredentism. Subsequently, either Serbs or Croats needed Yugoslavia just for very practical reasons but not as a consequence of some deeper ideological convictions into a common Serbo-Croat ethnic origin, reciprocity, and solidarity.

The “Idea of Union” of the South Slavs or only the Yugoslavs (the South Slavs without the Bulgarians) in a single national state had relatively deep roots in the historical development of political ideas among the South Slavs as it dates back in 1794. This idea had several stages of development and the features of expression but, basically, the supporters of the “Idea of Union” primarily understood the Serbo-Croatian cultural, national and political cooperation, reciprocity, solidarity and finally (political) unification as a “backbone” of any kind of a South Slavic state’s organization (with the Bulgarians or not). The idea was imagined to be realized in two phases:

1) The Yugoslav unification (the Serbs, Slovenes, and Croats).

2) The South Slavic unification (the Yugoslavs and Bulgarians).

However, historically, there were two ideas of the Yugoslavism: the Austrian and the South Slavic. The first advocated the solution of the Yugoslav Question within Austria (Austria-Hungary from 1867) while the second outside of the Dual Monarchy. Which idea will finally win depended primarily on the result of the military conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. Finally, the second option was realized due to the results of the Great War in which Austria-Hungary disappeared as a state.

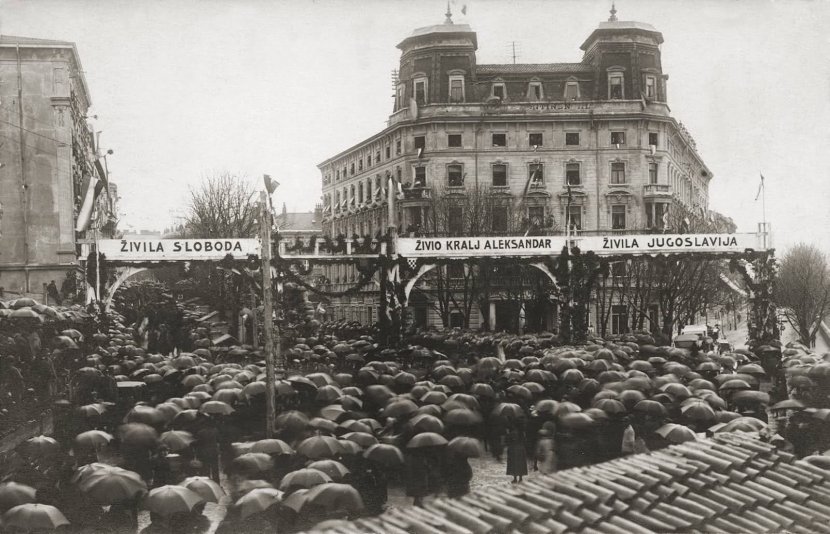

Undoubtedly, Serbia and the Serbs in general, mostly suffered during the WWI among all South Slavs and Serbia as a country paid the highest price for the post-war Yugoslav unification even sacrificing her statehood and internationally recognized independence for a newly established state which became in practice only a patchwork of many unbridgeable historical, cultural, regional, ethnic, and ideological differences. It became clear from the very beginning of the existence of a new state (the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, from 1929 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) that it is going to be impossible mission to organize a functional state due to its many differences just by the imposition of the ideology of an “integral Yugoslavism”.[18]

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2018

[1] Milorad Ekmečić, Stvaranje Jugoslavije 1790–1914, vol. II, Beograd, 1989, p. 523.

[2] “General Potjorek to Bilinsky”, Sarajevo, July 1st, 1914, Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, Fond ZMF, 778; Đuro Šurmin, “Jugoslovenska omladina posle aneksije BiH 1908”, Kalendar “Sv. Sava”, Zagreb, 1934, p. 4; Tin Ujević, Borba nacionalističke omladine, Beograd, 1930, p. 88.

[3] Milorad Ekmečić, Stvaranje Jugoslavije 1790–1918, vol. II, Beograd, 1989, pp. 537–538.

[4] Ivan Janez Kolar, Preporodovci 1912–1914, 1914–1918, Kamnik, 1930, p. 167.

[5] Dr. Jaroslav Šidak, Dr. Mirjana Gross, Dr. Igor Karaman, Dragovan Šepić, Povjest hrvatskog naroda 1860–1914, Zagreb, 1968, “Hrvatski narod u razdoblju od g. 1903 do 1914”, p. 106.

[6] Pero Slijepčević, Mlada Bosna, “Napor Bosne i Hercegovine za oslobođenje i ujedinjenje”, Sarajevo, 1929, p. 192.

[7] On the role of Serbia and Montenegro in the Balkan Wars of 1912−1913 see in [Борислав Ратковић, Митар Ђуришић, Саво Скоко, Србија и Црна Гора у Балканским ратовима 1912−1913, Друго издање, Београд, 1972].

[8] Trpimir Macan, Povijest hrvatskoga naroda, II. izdanje, Zagreb, 1992, p. 300.

[9] Franjo Tuđman, Hrvatska u monarhističkoj Jugoslaviji, Knjiga I, Zagreb, 1993, p. 31.

[10] One of the most important Croatian poets of that time, Silvije Strahimir Kranjčević, devoted his poem about Moses exactly to Ante Starčević who was seen in his eyes as a Saviour of the Croatian nation [Ivo Goldstein, Croatia: A History, London, 1999, pp. 98−99].

[11] ibid., pp. 135−140.

[12] Riječki Novi list, V/1911, No. 301, December 19th, 1911.

[13] Mirjana Gross, Agneza Szabo, Prema hrvatskome građanskom društvu: Društveni razvoj u civilnoj Hrvatskoj i Slavoniji šezdesetih i sedamdesetih godina 19. stoljeća, Zagreb, 1992, 157−170.

[14] Frano Supilo, Politika u Hrvatskoj, Zagreb, 1953, pp. 206–208; Antun Radić, Sabrana djela,vol. XVIII, Zagreb, 1938, pp. 187, 335–336.

[15] More information about it in [Većeslav Wilder, Dva smjera u hrvatskoj politici, Zagreb, 1918].

[16] Josip Horvat, Politička povijest Hrvatske, Prvi dio, Zagreb, 1990, p. 282.

[17] Ivo Goldstein, Croatia: A History, London, 1999, pp. 93−94.

[18] Andrej Mitrović, Prvi svetski rat, Prekretnice novije srpske istorije, Kragujevac, 1995, p. 89.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Personal disclaimer: The author writes for this publication in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS