An Albanian family around 1910

Views: 796

Preface

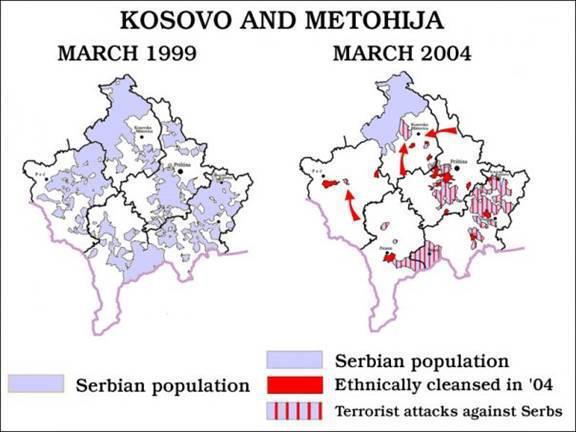

Kosovo (Serb. Kosovo-Metochia, Alb. Kosova) is a square-shaped province of the Republic of Serbia of 10,877 sq. kilometres that is approximately the size of the USA state of Connecticut. The province is situated in the southern interior of the Balkan Peninsula in South-East Europe.[1] For most of the 20th century-history, this province was part of Serbia like in the Middle Ages but from 1455 to 1912 it was occupied by the Ottoman Empire. After the 1998‒1999 Kosovo War the province is an autonomous territory under the formal administration of the UNO but, in fact, USA’s colony. Officially, the province has a population of some two million people, roughly equivalent to that of neighboring North Macedonia and ex-Yugoslav republic Slovenia. After the ethnic cleansing of the Christian Orthodox Serbs after June 1999, Kosovo-Metochia in inhabited primarily by the Muslim Albanians (up to 96%) followed by the ethnic minorities as the Serbs, the Bosniak, the Roma, and the Turks.

However, the real historical anomaly of the ethnographic breakdown of the province is a fact that in 1455 there were only up to several per cents of the ethnic Albanians in comparison to the rest of the inhabitants – the Serbs, who played a crucial cultural, ethnographic, and political role in the history of Kosovo-Metochia – the region that was „the birthplace of the first independent Serbian state“.[2] This province is one of the best-known examples in Europe as on one hand disputed land of highest inter-ethnic tensions and conflicts but on another hand as the territory of intermixed and cohabited areas of oppositely different cultural, confessional, mental and customary ethnic groups – the Christian Orthodox Serbs and the Muslim Albanians.

The purpose of my personal research presented below is to highlight some of the focal characteristics of Kosovo’s ethnically intermixed ethnography for the sake to as better as understand ethnic, cultural, confessional, ideological, political, historical, and all other important relations between the Serbs and the Albanians in this Serbia’s province and the region of South-East Europe.

The Customary Law: Leka Dukagjini’s Codex

The Customary Law: Leka Dukagjini’s Codex

Since North Albania was practically beyond any kind of the reach of the state’s law, even the state itself, the traditional ethos had to be subjected to a number of regulations, so that the society retains some political and social stability for the sake to survive and function. The serious crime cases, like murders, had to be somehow sanctioned, in particular in view of the ensuing blood feud – vendetta.[3] This finally has resulted in in the case of North Albania in the so-called Leka Dukagjini’s Codex which regulated the legal basis of the relations within and between tribes.[4] The origin of this collection of rules and regulations remains for the researchers so far obscure. The Albanians tend to ascribe it to a local ruler Leka Dukagjini, a contemporary of a national hero Skanderbeg.[5] The Albanians ascribe to him the codex known in the Albanian language as Kanuni i Lek Dukagjinit[6] (or simply Canun). Another interpretation has been that in all probability the Italian rulers in the late Middle Age composed the codex, Lex Ducagin,[7] which has been subsequently corrupted and converted into the name adopted today.[8]

The principal aim of the Codex has been to interrupt the endless chain of blood feud revenge. It proscribed the procedures for settling the disputes and for preventing further murders. Financial or natural compensations for killed or wounded were determined and the besa (oath) was required from the latest victim’s family that the blood feud is terminated.[9] Among the Albanians, the besa (Alb. besë) was and still is a very popular custom that is one’s word of honor, a sworn oath, a pledge or a cease-fire. In general, in the Albanian culture, the besa is regarded as something that is sacred and its violation was, in principle, quite unthinkable. However, the besa was not only a moral virtue but as well as the especially significant institution and instrument in the customary law among the Albanian population in North Albania and later in Kosovo-Metochia when the North Albania’s tribes occupied it. Among the feuding tribes of North Albania’s regions of the Accursed Mountains the besa, in fact, offered the only successful form of real protection and security and could be given between either individuals or feuding families for a very specific period of time for the sake to give them the opportunity to settle some urgent affairs. It could be as well as concluded between whole tribes as a cease-fire between periods of fighting.[10]

In modern times, blood feud was tackled by forming the so-called village councils, where old men with a good reputation and high credibility were engaged in the long procedure of reconciliation disputed families. It is claimed by the Albanian politicians from Kosovo-Metochia (KosMet) that these councils have succeeded in eliminating blood feud in this region after WWII, but, however, it has more a political propaganda background than actual facts from the ground.[11] It is worth mentioning that the same claim was made by Enver Hoxha’s regime in Albania, although with probably more justification.

A Yugoslav jurisdiction, in practice, had to cope with an Albanian ethos in both Kosovo-Metochia and Macedonia and to adjust its punishment system to the ruling ethics practiced on the ground. Even when the murderer is punished and imprisoned, the blood feud remains as a real threat. The prisoner has a leave of absence from the prison when he is allowed to spend some short period at his place of living. However, the authorities must first make inquiries at the local village authorities as to the opportunity for letting the prisoner go to his place. If the local authorities conclude that it would be risky for the prisoner, he would be retained in prison. Of course, the problem remains what to do after the punishment is over and the convict finally must leave the prison. The point is that the Codex does not care about justice and social order. Blood feud rests on the wounded pride of people, individual or collective. The state punishment is of no concern of these proud and pathologically sensitive people, it does not relieve them from their feelings of being humiliated and their self-respect fatally damaged. In fact, the local surrounding blames the victim’s relatives for not taking steps for avenging the murdered member of the family, tribe, etc. They experience it as a common humiliation and encourage the relevant relatives “to take the blood for blood”.

It is known that the blood feud has been present for centuries at Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica, as another sign that these islands parallel the Yugoslav highlanders from Dinaric regions in many respects. Mafia avenges have been notorious for that matter, even in the USA, transferring thus the ethos of traditional societies to the modern states.

Here it is dwelled on the blood feud in some detail not because it appears to the modern mind as a curious remnant of the ancient ethos from the traditional society[12] but rather as it has the most profound effect on the present-day society in this part of the Balkans, and has given rise to the most serious conflicts and atrocities in the region in the last century. In a sense that the whole conflict between the Albanians and the Serbs in Kosovo-Metochia, and generally between the ethnic Albanians and the neighboring peoples for that matter, it may be regarded as the phenomenon of the collective blood feud. The vanity pathologically developed within a Dinaric region in Yugoslavia, coupled with an extreme sense of proudness, appear common both to Slavenophonic Herzegovians and the Montenegrins as well as an Albanophonic population of North Albania, but in the case of the ethnic Albanians, it takes the form out of all proportions. It is for this reason that the Albanians do not mix with other nations.

The Albanians brought with themselves to KosMet the blood feud when they started in mass to settle this region from North Albania after the First Great Serbian Migration from KosMet in 1690 led by a Serb Patriarch Arsenije III Crnojević[13] by crossing the Accursed Mountains (Prokletije in the Serbian language) – a range of peaks extending along the present-day Albanian border with Montenegro and South Serbia’s region of KosMet. The range is called in Albania as the Albanian Alps. The highest peak of the Accursed Mountains is in KosMet – Mt. Djeravica (2,656 m.), which is at the same time the highest mountain peak in KosMet. In other words, the Accursed Mountains for centuries protected the region of KosMet from the Albanian invasion up to the turn of the 18th century when the Ottoman authorities invited neighboring Muslim Albanians from North Albania to settle depopulated and extremely fertile region due to the Serbian mass emigration.[14] However, historical sources clearly claim that up to the end of the 17th century the ethnic Albanian population in KosMet was very tiny – several per cents. For instance, even the Albanian historiographers recognize the very fact that according to the first Ottoman census in the region in 1455 there were only 4 to 5% of ethnic Albanians in KosMet.[15] However, one of the most significant outcomes of the Albanian massif occupation of KosMet since around 1700, alongside with the extensive Islamization of the region, was a new practice of the social relations among the Albanian highlanders and newcomers – the blood feud, which, actually, soon became transformed into the collective instrument of the settling interethnic relations with the Serb lowlanders.[16]

Although the blood feud is substantially restricted in Albania during the Socialism times, it has remained a prominent feature of the Albanian society in North Albania but in KosMet too as a result of a revival of the practice of vendetta since the fall of the Socialist regimes. In both Albania and KosMet, during the last three decades, there were many anti-vendetta campaigns which included several prominent figures who propagated in the favor of the extermination of the blood feud practice. For instance, one of them was Anton Chetta (Çetta, 1920‒1995) born in KosMet’s Djakovica and spending the youth in Prizren. He made his name in KosMet with the collection and codification of the Albanian oral literature in particular from the most nationalistic region of Drenica. He as well as became well-known as the participant in a widespread anti-vendetta campaign at the Priština University and in the mass media. Anton Chetta was in the 1990s, in fact, the aging scholar who led a committee of prominent Albanians from KosMet with the purpose to solve many blood feud cases that were ravaging the Albanian society in this province of South Serbia. In the course of many public rallies he and his committee succeeded to pacify over 900 vendetta cases, and, therefore, saved the lives of many of the men from around 4,000 Albanian families involved into the blood feud.

The Conversion: The Crypto-Christianity

Another historical feature of the region of Kosovo-Metochia is the so-called Crypto-Christianity which started to exist after the Muslim-Albanian invasion of the region from North Albania since the turn of the 18th century. This phenomenon is known across the Ottoman Balkans and it is a form of popular belief.[17] In essence, the Crypto-Christians have been those ex-Christians who because of different reasons accepted Islam. They were adhering to their old Christian belief in the private domain but officially on public places professed newly accepted Islam. Many of them had two names: a Christian name for private use and a Muslim one for public use. In KosMet, the Crypto-Christianity was particularly common in the region of the town of Peć, where the headquarters of the Serbian Orthodox Church was and on the Plain of Kosovo where historical Battle of Kosovo occurred in 1389. In Albania, the Crypto-Christianity (Alb. laramane or mixed) was widespread at least in the first generation after the conversion to Islam and especially in those regions in which the Ottoman authorities were weak or did not exist.[18] The practice of the Crypto-Christianity in many cases often resulted in a syncretism of folk beliefs and rituals.

What concerns Serbia’s province of Kosovo-Metochia, a phenomenon of the Crypto-Christianity was in direct connection with both Islamization and Albanization of the local Christian Orthodox Serbs.[19] In other words, newly Islamized and Albanized Christian Orthodox Serbs – the Arnauts, have been for a while, in fact, the Crypto-Christians who secretly in their homes professed the Christian faith. They and their children often had double names – one official Muslim and another private Christian. The Arnauts, at least in the first and second generation after the Islamization and Albanization, used to speak both languages – the Serbian and the Albanian.[20] However, those converts later became according to the 19th century-reports by Serbia’s consuls in Priština, the most fervent persecutors of the Christian Orthodox Serbs in KosMet but as well as well-known Muslim bandits and even the „Albanian“ national heroes and leaders.[21] Some of those leaders even did not properly speak the Albanian language but only the Serbian one.[22] The Arnauts, in fact, did not have a proper national identity as they have been between the Serbs and the Albanians. They could not be the Serbs as they, in this case, had to be the Christian Orthodox but on other hands, they also could not be the Turks or the Albanians as they did not speak either the Turkish language at all or the Albanian language properly.[23]

Ethos, Guns, and Demography

In remote mountainous Balkan areas, far away from law and state’s control, wealth and security of a family rest on the number of guns it possesses or better to say on the number of people they are capable of shooting and fighting in general. Guns are needed for many purposes, in fact, but the following three are the most important in the Balkan case but primarily concerning Albania, Montenegro, and Herzegovina:

- It secures the house from the neighbors, from plunders, like highwaymen, from wild beasts like wolfs, jackals, bears, mountain lions, etc.

- It enables the family to plunder its neighbors, plane people, to execute blood feud, etc.

- In the case of a common threat from the outside, like a foreign invasion, join efforts of many families, tribes, etc., secure the successful defense.

However, in the case of ethnic Albanians, in addition to all three mentioned purposes, the principal rationale for keeping the house well-armed is the imposition of a blood feud (vendetta) and protection from the same. Strong family secures its authority and hierarchical position within the tribe (Alb. fis) and many guns deter eventual aggression from other tribes. Therefore, it is imperative to have as many sons as possible and also as many guns as the family can afford. This condition sine qua non has imposed a particular social ethos among the Albanian highlanders which they brought to Kosovo-Metochia (KosMet), both with respect to the outside and inside of the family.[24] The response to this requirement has been simple: the women are supposed to give as many births as possible but particularly to the sons. As a consequence of such ethos, the highlanders’ women spend the best years of their life by giving births and raising the children. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced among the Muslims, due to the already subordinate position of women in the Islamic society in general.[25] And when this anthropological affair is combined with political aims, as the case with the Albanians in KosMet, in fact, is, then the high birthrate passes into the demographic explosion. And here we come to the crux of the Albanian Question in general and the KosMet issue in particular.

Under primitive, poor conditions and lack of proper medical care, the majority of births are either abortive or the babies fall victims of improper care. As testified by Edith Durham,[26] she was shocked by the treatment of the Albanian babies, who were held in their cradles covered by blankets, so that babies could hardly breathe. All this resulted in a very high proportion of baby mortality. If we recall that hundred years ago only three or four of 8 children would have survived, we can understand the origin of the demographic explosion going on with ethnic Albanians. However, for even under modern medical and other conditions the Albanian couple would not stop at three children if they are daughters, and it is only males that matter in the rural traditional society. Nevertheless, another peculiar feature of the ethnic Albanians’ breeding attributes is that the first children are usually females, so that males appear minority in the Albanian society, at least in KosMet. This has given rise to a peculiar custom, known particularly among Albania’s Albanians.

If the wife does not stop giving birth to daughters, all siblings consist of female offspring. The farther feels humiliated, with grim prospects for his family. In that case, one daughter, usually the eldest or boy-like one,[27] takes over the role of (an unborn) son (in Dalmatia, the so-called Virdžina).[28] She (Virdžina) dresses as male, carries a gun, smoking tobacco, getting more food, and gradually becomes indistinguishable from males. It is her/his duty to protect the family as well as to exercise blood feud, if necessary. She/he is accepted by the whole community as male, never marries and dies as a man.

It is fair to say that the whole Dinaric region of ex-Yugoslavia and North and Central present-day Albania have been notorious for high fertility. These mountainous areas appear to be a traditional source of surplus population, which moves down to fertile planes and assimilates gradually into the indigenous people. All regions of West Balkans are populated by a mixture of the autochthonous and incoming populations. If the migration is reasonably gradual, the process takes on acceptable socio-demographic forms. However, in practice, the problem arises in two cases:

- If the migration (in fact, occupation) is massive and relatively within a short period of time as, for instance, it was the case of the First Serbian Migration in 1689−1690 from KosMet to the Habsburg Monarchy.[29]

- If the newcomers are ethnically different, speaking a distinctly different language as, for instance, in the KosMet case (the Albanian newcomers of highlanders vs. the Serb autochthonous lowlanders).[30]

Marriage and Family

The physical geography conditions surely have shaped the mental and physical structures of these two distinct populations – the Serbs and the Albanians. In the fertile plane, which provides easily living goods, people tend to be mild, industrious, and not very cute. Their social motto is “take it easy” and tensions between the members of kuća − the traditional counterpart of a Dinaric zadruga (in the Serbian) and fis (in the Albanian) regions − are rare and resolved in a reasonable manner. Although this kind of old society has been largely disintegrated in modern times, the tame features of these rural people can still be recognized. However, on the contrary, harsh and strict rules which were governing internal and external relationships among the highlanders are still present in the Dinaric regions, especially the Albanophonic. The severe living conditions, on the soil largely devastated by cutting woods, sheep and goats grazing, etc., have shaped a tough and violent mental structure of these inhabitants in the mountainous areas. The ethos of these people might well be summarized by Hobbs’ homo homini lupus.[31]

Unlike the lowland regions where the division on male and female is very weak and where the head of the (extended) family, elected regularly yearly, might be a woman, a separation between male and female members of highlanders’ zadruga (fis) appears strong and strict. Generally, women constitute a subordinated part of the highlanders’ community, both within family and tribe. This is particularly pronounced among the Muslim Albanians, where a female member of fis is regarded almost as domestic cattle. They live in separate parts of the house, never appear before a stranger, and go out only on exceptional occasions and even in this case under attentive supervision of a male member (usually with the gun). Before WWII, women used to wear feredža, a kind of chador of the contemporary fundamentalist Muslim (Arab) women. The Communist Governments, both in ex-Yugoslavia (Titoslavia)[32] and neighboring Enver Hoxha’s Albania,[33] managed with great difficulties to remove feredžas from Muslim women faces. Generally, in the urban areas, the situation is much more favorable concerning this issue, but in rural regions, the old customs and conservative traditions still prevail. Girls are married at an early age, for the boy they sometimes never met before, all arranged by the older male members of the family. If a woman has to go to the doctor, she is escorted by a male member of family, husband and like. The latter ensures that she will be treated by a female doctor and even then the male supervises the examination. Marriage appears as a business affair rather than a social event.[34] Father of the girl to be married gives to groom’s family a substantial amount of money and goods (usually in the form of cattle, eventually land). If marriage is to be broken for the husband’s “guilt”, this money must be given back to the girl’s family, together with the girl herself.

However, what makes the life of the Muslim women in general and ethnic Albanian in particular, often unbearable, is the pathological jealousy of husbands.[35] It is sufficient to look at somebody’s woman to provoke a nervous reaction. Such sensitivity to women attraction provokes troubles, including murder. Almost all disputes and murders among ethnic Albanians are caused by “women affairs”, which usually triggers crime and the curse of blood revenge. The same sensitivity prevents the disputed parties even to mention women at court and the disputes are regularly disguised as innocent quarrels over borders, trespassing and like that. It should be stressed here that women themselves are never direct victims in these disputes. The common law (Leka Dukagjini’s Codex) strictly forbids killing female members of the society and if it does happen it is strongly condemned.[36]

This situation is further strongly aggravated by the institution of Gastarbeit, going to West Europe, particularly to Germany, for work. While some other nations, like the Turks, for instance, take along their family, the ethnic Albanians never do that. They live in a foreign country and send home part of their earnings, visiting the family twice a year, on average. Upon arriving home, the first thing to do is to make another child, leaving then the wife pregnant behind. Besides gaining another member of the family, hopefully male, he secures that his wife will remain faithful during his absence. From her side, she is satisfied by the course of events, for a new child means her bigger security in the family.

Contrary to what is described above, the lowlanders suppress maximally their fertility. In order to preserve the family estate intact, the institution “one family, one child” has been practiced in modern time in ex-Yugoslavia in Vojvodina, Slavonija, Šumadija,[37] Zagorje,[38] etc. The outcome of this suicidal practice has been the decrease of populations, at least of the autochthonous one, in these areas. The phenomenon has been dubbed “white plague”, for good reasons, for the rural regions of the non-Dinaric Balkans have been in the process of biological dying for the last century. The process has been slowed down to some extent by the influx from Dinaric regions. The relations in this matter between the highlanders and lowlanders are like ”predator–pray” correlation, for good reasons. The highlanders have always looked down to the lowlanders as the “fertile soil” for robbing and plundering. It is this outlook that has prompted Hannibal and Bonaparte, to mention just two examples, to urge their soldiers, while looking at the reach Lombardy from the high Alps, to descend and “collect the harvest”. In the Balkan western Dinaric region, during the Ottoman occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Herzegovinians regularly made guerrilla invasions to the lowlanders and robbed them. These plunders were called uskoks,[39] and used to be highly valued by the local epic poets. The reason for the latter was that it was mainly the Turks that were attacked and these exploits were painted by patriotic colors.

A “Patriotic” Banditry

Here, two more phenomena of our interest have to be mentioned. Both belong to the highwaymen movements and were common to the Balkan history of the highlanders generally. In the Slavonic-speaking Balkan regions these highwaymen were called as the hayduks and in the Albanian-speaking areas as the katchacks (from the Turkish language kaçak, highwayman or simply bandit).[40] Their common practice was to make an ambush and rob the trade caravans, usually killing the tradesmen and escorts. Since these banditry movements were very prominent during the time of the Ottoman Empire, the hayduks were considered national heroes and freedom fighters for the national liberation. The best illustration of the last point is the epic poem Gorski vijenac,[41] written by a Montenegrin theocratic ruler Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (1813−1851) in 1847. The political motivation for the writing this poetic drama was the acute threat of bishop’s subjects converting into Muslims, under the pressure of economic poverty and famine.[42] The subject of the poem was “the extermination of poturice[43]”, a sort of “religious cleansing”. In fact, the event the poet referred is consisted of five families killing their Muslim neighbors (and relatives at the same time). However, this historical event was hardly noticed at the time when it occurred. This point, nevertheless, illustrated well another important feature of a Balkan highlanders’ mentality – they are prone to the exaggerations out of all proportions. But, in essence, it was the silent message of the legalized highwaymen’s banditry (more precisely of uskoks’ practice).[44] This aspect has never been exposed in the Serb/Montenegrin exegesis of this poetic drama, though the latter is extensively worked out at the grammar schools in Serbia and Montenegro.[45] Njegoš’s Gorski vijenac (The Mountain Wreath) has, by the way, the reputation among the Serbs as the Serbian Iliad.[46]

However, in fact, the Ottoman Turks themselves used to use this practice in a well-organized manner as a means to extend their state’s territory and authority. Their infamous bashi-bazouks, cavalry bandits, who used to plunder areas across the borders by brutal and sudden assaults are well-known in the history of the Ottoman Empire.[47] This practice resulted in emptying the ranger territories from the indigenous inhabitants, which enabled the Ottoman forces to occupy these areas easily when an official war was initiated. It is important to mention this practice here because it was exactly the same tactics which KosMet’s Albanians exercised after the UNMIK (the United Nations Mission in Kosovo) occupied KosMet in June 1999 and when the local army control was handed over to the ethnic Albanians who did ethnic cleansing of the Serbs.[48] Here has to be mentioned as well as banditry raids made by the Albanians from the newly founded state of Albania, after WWI. These raids into KosMet become so annoying that the regular army of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes[49] was forced to enter Albania’s territory for the sake to pacify the region from the aggressive bandits of North Albania’s highlanders. The Albanian Government then addressed the newly founded League of Nations for the protection and the latter ordered Yugoslav armed forces to withdraw from North Albania. However, the Yugoslav Government did not take it seriously and newspapers in Serbia commented on the requirements by “Let us see who is stronger – the Serbian army or the League of Nation?” In fact, it was the first intervention of newly established international organization founded to ensure the world’s peace and it was important that the intervention succeed. The Yugoslav Government in Belgrade had to comply and withdraw its military forces from North Albania.[50]

The practice of the hayduk banditry remained in the Balkans even after the rule of the Ottoman Empire and was uprooted, for instance, in Serbia only in the very late 19th century. However, in KosMet this tradition has been alive even up today among Muslim Albanians. One of the permanent testimonies of the practice of robbery is the gorge Kačanik (Kaçanik), between Serbia’s southern province of KosMet and the Republic of North Macedonia. The name of this unavoidable passage for those traveling between these regions has been derived exactly from the term katchak or the highwayman (bandit, robber) in the Albanian language. Only under a heavily armed escort, it was possible and advisable for caravans to go through the gorge. The Serbian epic poetry has recorded this usage of Kačanik, albeit in an allegorical form, in the poem on duel (megdan) between Marko Kraljević (a Serbian epic hero, otherwise historic ruler of the feudal possessions in Vardar Macedonia around the town of Prilep) and Musa[51] Kesedžija (his ethnic-Albanian counterpart).[52] The duel resembles that one between Achilles and Hector and the (anonymous) poet showed equal sympathy for both adversaries, just as its famous Greek counterpart did the same regarding the Greek and Trojan heroes.

A very undesirable consequence of the hayduk banditry was that state allowed civilians to keep and carry guns, as protection from the highwaymen’s banditry. Even the Ottoman Turks tolerated this in the Christian provinces. However, a state with armed civilians is not a real state at all like the USA (Wild West) is not, for example. It is well illustrated by uprisings within the Ottoman Empire, which were successful, at least temporarily, just owing to the armed rebellious populations, as the case of the First and Second Serbian Uprisings in1804−1813 and 1815 shows well.[53] When king of Serbia Milan Obrenović in the newly independent after the 1878 Berlin Congress tried in 1883 to collect weaponry from the peasants in East Serbia on the border with Bulgaria (Timok region), since he established the regular army, it resulted in an armed rebellion (the 1883 Timok Rebellion from November 2nd to 13th), which the Government suppressed only with great efforts.[54] Тhis phenomenon will be the cause of many troubles with the ethnic Albanian population, both in Serbia and Albania. If one realizes that it is the highlanders who are troublemakers in West Balkans, with their cult of weaponry, he/she can appreciate this devastating effect on the weakly civilized societies in the region.

How much the guerrilla-banditry tradition is esteemed in modern Yugoslavia testifies the number of soccer clubs with the name Hajduk (highwayman), including the most popular one in Croatian Dalmatia from Split (est. in 1911 as the Serb one). At Sinj in Croatia, every year there is the festival called Sinjska alka, with competitors in the traditional military uniforms, trying to pick up a ring by their spears, riding horses, which commemorates the times of the Uskoks and their raids across the Ottoman border in Bosnia-Herzegovina and part of Dalmatia (from the territories at that time of the Habsburg Monarchy and the Republic of Venice). An overwhelming majority of military leaders in the Serb uprisings in the 19th century have been actual or former hayduks,[55] including the supreme commander Karađorđe (1762−1808).[56]

Nevertheless, such guerrilla-banditry tradition was revived in Yugoslavia, first in Vardar Macedonia just before the Balkan Wars (1912−1913), during the WWII (the Partisans of Josip Broz Tito and the Chetniks of the General Dragoljub Draža Mihailović), then in the period of the civil wars (1991−1995) and finally during the 1998−1999 Kosovo War (the US-sponsored Albanian Kosovo Liberation Army).

Lebensraum

One of the most interesting, focal, and surprising features of the culture and ethnography of the ethnic (Muslim) Albanians in Kosovo-Metochia (KosMet) is their extremely high level of natality compared with both Albania and Europe. However, for the sake to properly analyze this phenomenon, it has to be taken into account two parallel processes:

- The spontaneous breeding in the population still tied by the traditional and conservative way of life.

- The attitude of the political leaders in view of their political ideologies and national aims.

The first phenomenon cannot be, in fact, separated from the later, but, nevertheless, the link between them is not of direct nature. In other words, the Albanians, in general, found themselves, at the time of their national revival (Rilindja, 1878‒1912), surrounded by more numerous nations, like the Greeks and the Serbs.[57] They felt that a more balanced equilibrium will ensure the existence and growth of projected exclusively ethnic Albanian state in the future. However, this idea could be achieved by two processes: rapid increase of the ethnic-Albanian population, and by collecting all Albanian-populated regions into a single state ‒ a Greater Albania. While these aims were a more conceptual long-term project in Albania proper, the ethnic Albanians outside homeland (Albania) experienced this goal as an acute affair, to be achieved as soon as possible and, most important, by all means including ethnic cleansing of non-Albanians.[58]

In general, the feeling of ethnic endangering may provoke two opposite responses of the population (nation):

- A pessimistic outlook – natality drops and the population diminish in number. This case, for instance, was with North-American Indians, confined in reservations.[59]

- An optimistic attitude – natality rises so as to compensate for the feeling of national minority and/or inferiority. It has to be noticed that for the Dinaric highlanders (or many other highlanders) the word “minority” sounds humiliating indeed.[60]

A historical fact is that the Albanians, both in Albania and surrounding countries, opted for the second alternative, but the essence is that giving birth to children has become an obsession and national task. However, this choice bears much risk, considering the non-Albanian environment as such policy has to ensure an expansion space (Lebensraum), both physical and political and those non-Albanians who raise the issue are proclaimed to be nationalists and even racist chauvinists, obsessed by the Albanian birthrate.

The principal targets of the latter point are the Serbs and the Macedonians, whose populations in their countries are “losing ground” before the “biological tsunami” of the fast-breeding ethnic Albanians. Both the above points have made the demographic explosion taboo. Anybody who wants to check what it means can do it but at his/her own risk. One should be aware, however, that there is an essential difference between urban and rural areas in this context. Those living in towns are much better educated and practice family planning, whereas the peasants appear immune to any medical and social education. Since the urban population shares approximately 20% of the overall population at KosMet and considering that an outsider is very improbable to meet a peasant (and if he/she does meet him/her to be able to talk to him/her), the natality syndrome appears well concealed for the “outside world”.

Regardless of the fact that probably a phenomenon of the Albanian “abnormal” natality to someone might sound like a kind of an act of consolation, but, in fact, it was and still it is a political tool for appropriating the land they have found themselves to live on. That this is not a unique instance of the use of biological means for achieving political aims is perhaps the best illustrated by the famous sentence by Yasser Arafat: “Our atomic bomb is the womb of Arabic woman!”[61]

Nevertheless, it does it mean that if a population resort to higher fertility that its collective existence is really endangered. In the case of North America’s Indians, such an attitude would surely gain support in South America’s Europe’s population. On the other hand, the Nazi politics of Arian-race fast breeding was motivated by an aggressive attitude towards “lower-race” nations and had nothing to do with real national or/and political needs. It was obviously the product of a sick mind, a collective paranoia, initiated by the paranoid mind of a genius of evil, Adolph Hitler.[62] One cannot help recalling how he started with slogans of humiliated, endangered, etc., a German nation. The present-day Albanian-supported and propagated quasi thesis about the Albanian Illyrian origins and ethnogenesis perfectly matches a Nazi neo-Paganism. It begs no great imagination as for the Jewish counterpart in the KosMet issue, as far as the concept of “evil” is concerned.

The common case of the Albanian family life in KosMet since the mid-1960s is the following:[63] The father (pater familias) works as the gastarbeiter (guest worker) in Germany or elsewhere in West Europe, sends money home, visits home twice a year or so, counts the children and then returns to job abroad. The children are raised by his wife, frequently illiterate woman and children grow practically “in the lane”.

It has become obvious since long time ago, both to the domestic political leaders and politicians abroad that such a demographic explosion of ethnic Albanians in KosMet and the Yugoslav Macedonia will give rise to an unstable situation, politically, educationally, and economically. Within Yugoslavia, those republics who used to provide the contributions to the federal fund became less and less willing to feed the Albanian demographic explosion in KosMet. Although KosMet’s population shared less than 7% of the overall Yugoslav one, 33% of the federal fund went to KosMet. It has become clear since a long time ago that it was family planning which could stop this demographic explosion only and balance the rate of growth and the economic welfare. However, the focal question became: Why it has not been undertaken?

In essence, it has been tried something to do as, for instance, in the 1970s a UN fund donated 100.000 $ to KosMet for organizing family planning education. It has to be noted that at that time it was a large sum, equivalent to the present-day sum of several million dollars. But what happened to this money? Simply nothing as nobody took a dollar from this fund. Was this an outcome of a political decision to deliberate keep the natural-birth rate as high as possible? Nevertheless, instead, to answer this crucial question, it has to be mentioned another instance of “channeled biology”. During the campaign in Serbia before the 1998−1999 Kosovo War for preventing the AIDS proliferation among youth, first of all, students, the latter complained that although they had the opportunity to make use of automats for condoms, the latter turned out often inadequate, since those to be used in KosMet were “too small”. How one can interpret this? As a chauvinistic boasting of non-Albanian Serbs? Or somebody’s deliberate supplying ineffective condoms to the Albanian youth?

Whatever interpretation of the demographic explosion on KosMet may be, it appears compatible with the political aims of the Albanian leaders there. However, the crucial point of the phenomenon already became that it is the common mantra of any international institution, individual or otherwise, when the KosMet issue is invoked, to stress from the outset that the ethnic Albanians are an overwhelming majority there. All other matters are then automatically subordinated to this point[64] or another side of the complete truth is simply “forgotten”.[65]

Guns and Power

Besides the natality, the weaponry is another obsession of the Albanians likewise of all Yugoslav Dinaric highlanders, in particular, the Montenegrins and the Herzegovinians. A weaponry smuggling practice appears to be one of three principal economic activities at KosMet. Another two are drug and people smuggling. However, the main amount of weaponry remains at KosMet. The principal route of weapon traffic goes from High Albania.[66] Since the border with Albania is very difficult to control, going along mountain crests, it is very easy to transfer a large number of weapons, from rifles, guns, bombs, machine guns, personal rockets, etc. (i.e., all kind of weapons except the tanks and the airplanes). During the peak of fighting at KosMet at the summer of 1998, caravans of horses used to carry weapons for the Albanian terrorist organization Kosovo Liberation Army (the KLA)[67] across the mountainous border with the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (the FRY). From one hand, the Yugoslav army succeeded to intercept many of those caravans, but from another many of them managed to get through and deliver the arms to the KLA. Which kind of activity it was is the best illustrated by the fact that many of those caravans were without man escort as the horses knew the rout “by heart”.

As it is well-known, a vast majority of the Dinaric highlanders’ households are well equipped with guns and KosMet has been no exception in this regard. This time, however, the situation attains an additional dimension, apart from the weakening of the state’s control of individuals. If those individuals belong to a particular, distinct subpopulation, like a hostile ethnicity, the sociological disaster becomes, in fact, a political one. It was for this reason that the Yugoslav authorities tried many times to collect the weaponry at KosMet from the Albanians, but, unfortunately, with a little effect. Contrary, in fact, all of those attempts provoked even stronger hostility towards Serbia, her authorities, and the Serbs as the nation. For that reason, for instance, the Ministry of Interior during J. B. Tito’s rule was in the hands of Alexandar Ranković (till 1966), Tito’s close crony even since WWII, who was the most hated man in Yugoslavia among KosMet’s Albanians as he intended to establish the order in this Serbia’s province.[68] Nevertheless, it is quite ironic to note here that the nickname of this minister was Leka, which coincided with the name of the Albanian Leka Dukagjini who was presumably the “legislator” of the Leka Dukagjini’s Codex, which dealt with the blood feud affairs among the Albanians. The Codex was a part of the general common law, the so-called Canun, which provided a rationale for the private possession of the weapons, as a substitute for juristic rule.[69]

As a matter of fact, hundreds of thousands of weaponry (700.000?) looted from the military magazines in Albania in 1997 we transported to KosMet. When in 2005 the KFOR ordered all weapons in private possession to be delivered to the authorities, out of wrongly estimated about just 300.000 pieces only 1.700 were delivered mainly old and obsolete arms. Today, it is a belief, there are still at least 400.000 weapons in KosMet in the possession of the ethnic Albanians. Here it has to be noted that historically (unsuccessful) arms collections were frequent at KosMet from the Ottoman times (for instance in 1910) to the present day (in 2005).

Now the crucial question in the matter is: How can a state-run if her subjects are fully armed (like in the USA)? In the following paragraph, it is going to be presented one incident at KosMet from the mid-1980s. It has to be noted, however, that at that time KosMet had practically a status of a republic within the Yugoslav federation, having all other prerogatives like all six Yugoslav republics except for the right to secede. Among other things, police patrols were of mixed type, with an equal share of the ethnic Albanians and non-Albanians (usually the Serbs).

A certain Albanian from the village of Gornji Prekaz committed a crime,[70] but the police forces were unable to bring him to the court. His house was close to the forest and whenever a police patrol came, he was warned in advance, run into the forest and after the patrol left the village, would return to his house and continued to enjoy the freedom. One day, however, he failed to run away in time and the police surrounded his house. As it is known, the Albanian houses in rural areas resemble small fortresses rather than the dwelling places. Police did not dare to enter the house, surrounded by a high wall and called the outlaw to surrender. After some negotiations, the latter agreed, with the proviso that they bring another police inspector, who happened to be a Serb. This inspector came and when all seemed arranged a policeman shot a bullet and a fierce shooting started. The fire from the neighboring houses joined that from the surrounded house and the scene looked more from a war movie than standard police intervention. Finally, one policeman was killed, the outlaw too, and his father and daughter (who played an active role in the shooting, too) were wounded. In other words, the battlefield was left with two corps, and two stretches.[71]

Education and Culture

The period from 1981 (the Albanian mass demonstrations and riot in KosMet) to 1999 (NATO’s aggression on the FRY) was characterized by a gradual and permanent alienation of KosMet from the rest of Serbia and parallel making ever stronger bonds with neighboring Albania. However, these bilateral bonds were prominent even earlier, particularly in the educational domain. The reason for this particular kind of links is a radical disproportion in the economic sphere between KosMet and undeveloped (post) Enver Hoxha’s Albania when, as a consequence, the Albanians from High Albania were emigrating to KosMet and the Yugoslav Macedonia as Yugoslavia for them was like West Europe.

The books, textbooks, and the literature generally used to be imported from Albania extensively. With them came well designed political and national Albanization of KosMet’s Albanians, in particular of the youth. In practice, it meant that Albania was propagated as a motherland of KosMet’s Albanians and, therefore, the political unification of KosMet with Albania was understood as something to be natural and democratic. On the other hand, Serbia and Yugoslavia were propagated to be hostile toward the Albanian national aims. The university professors from Tirana became the frequent visiting staff at the University of Priština while the university staff from Serbia was gradually removed from KosMet. The very main building of the University of Priština was built by the money from the federal fund, which was practically Serbia’s donation.

The political tension and mistrust were used to abuse the educational system. The lecturers from other universities engaged at the University of Priština had to exam the students, who pretended not to understand the Serbo-Croat, in the Albanian language. They would ask a question in the Serbo-Croat language, then the Albanian assistant would translate it to the student. The latter then is talking something in the Albanian, the assistant turns to the examiner and says “he knew” and the student passes the exam. Nevertheless, all this made the educational level at KosMet very low, making the university diplomas useless, even at KosMet itself. By implication, secondary and primary education was lowering down too, and the entire educational system practically collapsed. However, this truth passed unnoticed by external factors, but the most indicative sign of the state of art in this context is a practically total absence of KosMet science on the international scene, except for the Albanology. It has to be noticed that in the Yugoslav Macedonia (today the Republic of North Macedonia), where the Albanian population was even stronger in comparison to Serbia, there was no single Albanian-language university but in KosMet it was.

The local authorities resisted the educational curriculum prescribed by Serbia’s institutions, as an attempt to deAlbanize KosMet’s Albanians. In the literature subject, they complained that too many Yugoslav writers were present in the textbooks at the expense of the ethnic Albanian ones. Since those programs were conceived by the federal boards and since the Albanian literature appears to be poor as compared with the Croat, Serb or Slovenian, for example, this misbalance was simply a reflection of the actual situation. Besides, literature appears the best means to homogenize ethnically and culturally diverse population and to provide a feeling of the common state. To be honest, the vice versa is true too, a greater presence of the Albanian writers (particularly from KosMet) would do the same service to the idea of the common Yugoslav state.

Already in the 1970s, the Albanian students used to prefer the Universities of Zagreb and Sarajevo instead of the University of Belgrade.[72] On the other hand, Belgrade used to host tens of thousands of KosMet’s Albanians who became employed in the city public service. When the open hostilities between Belgrade and Priština started in 1998, those Albanian gastarbeiters silently disappeared from the Belgrade streets.

It is true that some graduates from Priština did come to Belgrade for doing their Ph.D. studies and the Serbian university lecturers (out of KosMet) were employed at the University of Priština but gradually as the links with Tirana gained in strength. Serbia practically became absent from her southern province. Students from KosMet were very rare indeed in the rest of Serbia, in particular in Belgrade. Part of this absence should be explained by the low standard of the knowledge which KosMet’s students acquired at the local schools and university and were, therefore, not enough qualified to be enrolled to Serbia’s universities out of KosMet. However, this absence of “youth intersection” broadened as a consequence further the gap between the Albanian and all other Serbia’s population. If the mixing of Central Serbia’s students with their colleagues from the University of Priština was stronger such animosity towards non-Albanians would have probably been less pronounced. At least the rest of Serbia’s population would have been aware of the hatred Albanian felt toward the rest of the citizens of Serbia.

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2019

[1] See [Moseley Ch., Asher E. R. (eds.), Atlas of the World’s Languages, New York‒London: Routledge, 1994, map 64].

[2] Palmowski J., Oxford Dictionary of Twentieth Century World History, Oxford‒New York: Oxford University Press, 1998, 339.

[3] The blood feud in the Albanian language is gjakmarrje.

[4] Бартл, П., Албанци од средњег века до данас, Београд: CLIO, 2001, 58.

[5] Giorgio Castriotto Scanderbech (according to one Italian drawing from the 18th century), 1405−1468 was, in fact, of the Serb ethnic origin from the father side. He came from a family of landowners from the Debar region in North-East Albania who were no doubt of mixed the Serbian-Albanian ancestry. Today, he is the focal symbol of the Albanian nationalism and, therefore, his equestrian statue after the 1998‒1999 Kosovo War stands in a very downtown of Priština regardless of the very fact that he personally has nothing to do with KosMet. The Germans during WWII created the Skanderbeg Waffen-SS Division, approved by Adolf Hitler in February 1944 as a volunteer force of KosMet’s Albanian nationalists who were terrorizing the Serb population. The Division participated in the rounding up of 281 Jews, who were deported to Bergen-Belsen death camp. The final activity of the Division was to assist the German troops in their withdrawal through and from KosMet in November 1944 [Elsie R., Historical Dictionary of Kosova, Lanham, Maryland‒Toronto‒Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2004, 169].

[6] Бартл, П., Албанци од средњег века до данас, Београд: CLIO, 2001, 55.

[7] This term comes from the Latin dux (Duke) for a local leader and from Gjin (John), i.e., Duke John. The Albanians are calling West KosMet as Dukagjin (in the Serbian language Metochia) just to avoid both the Christian Orthodox and the Serbian historical, political, and ethnographic roots of it. This is, in fact, the populated plateau running from the city of Peć to the city of Prizren (the latter is known as the “Serbian Constantinople” or the “Serbian Jerusalem”).

[8] It is one of the best examples how local mythology becomes “historical fact”.

[9] Бартл, П., Албанци од средњег века до данас, Београд: CLIO, 2001, 58.

[10] Elsie R., Historical Dictionary of Kosova, Lanham, Maryland‒Toronto‒Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2004, 25.

[11] About this issue, see in [Slađana Đurić, Osveta i kazna: Sociološko istraživanje krvne osvete na Kosovu i Metohiji, Niš: Prosveta, 1998].

[12] As recorded, inter alia, in the Bible, as dictum “eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth”.

[13] Arsenije III Crnojević (ca. 1633‒1706) of the Montenegrin origin became a Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Peć (West KosMet) in 1672 and, therefore, was both spiritual and political leader of the Serbs. During the 1683‒1699 Austrian-Ottoman War, which affected KosMet very much, in January 1689, when the Austrian army, defeated by the Ottomans, began withdrawing from North Macedonia (Skopje) and KosMet, they were accompanied by a large number of the Serb refugees who wanted to escape from the harsh Turkish revenge. The refugees were headed by the Patriarch, who fled northward with his people of around 100,000 to the safety of the southern parts of the Habsburg Monarchy. In June 1690 the Patriarch asked the Habsburg Emperor for the permission to settle his people in South Hungary (present-day Vojvodina in Serbia), and was granted land. This historical event is known as the First Great Serbian Migration from Kosovo-Metochia and is regarded as a turning point in the history of the region [Elsie R., Historical Dictionary of Kosova, Lanham, Maryland‒Toronto‒Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2004]. About history of KosMet, see more in [Самарџић Р., и други, Косово и Метохија у српској историји, Београд: Српска књижевна задруга, 1989; Krestić V., Lekić Đ., Kosovo i Metohija tokom vekova, Priština: Grigorije Božović, 1995].

[14] On the First Great Serbian Migration from KosMet, see in [Чакић С., Велика Сеоба Срба 1689/90 и патријарх Арсеније III Црнојевић, Нови Сад: Добра вест, 1990].

[15] Бартл, П., Албанци од средњег века до данас, Београд: CLIO, 2001, 59.

[16] About an ethnic history of the Albanians, see more in [Jacques E., The Albanians: An Ethnic History from Prehistoric Times to the Present, Jefferson, N.C.‒McFarland, 1995]. About the relations between the Serbs and the Albanians in the Middle Ages, see in [Šuflaj M., Srbi i Arbanasi: Njihova simbioza u srednjem vjeku, Beograd: Izdanje seminara za Arbanašku filologiju, 1925].

[17] Dawkins M. R., „The Crypto-Christians of Turkey“, Byzantion, Vol. VIII, Paris, 1933.

[18] Бартл, П., Албанци од средњег века до данас, Београд: CLIO, 2001, 52−53.

[19] On this issue, see more in [Хаџи-Васиљевић Ј., „Муслимани наше крви у Јужној Србији“, Браство, књ. XIX, Београд, 1925, 21−94; Урошевић А., Етнички процеси на Косову и Метохији током турске владавине, Београд: САНУ, 1987].

[20] Станковић П. Т., Путне белешке по Старој Србији 1871−1898, Београд, 1910, 105.

[21] See, for instance [Бован В., Јастребов у Призрену, Приштина, 1983; Батаковић Т. Д., Косово и Метохија: Историја и идеологија, Друго допуњено издање, Београд: Чигоја штампа, 2007, 49].

[22] One of such populated micro-regions in the 19th century is, for instance, Drenica Valley. Drenica is the geographical name of a hilly and mountainous micro-region in North-Central KosMet located between the Kosovo Field and the Metochia Plateau situated within the triangle formed by the cities of Priština, Kosovska Mitrovica, and Peć. The Drenica Valley is divided into two sub micro-regions: the Upper Drenica or the Red Drenica, to the North, and the Lower Drenica or the Paša Drenica, to the South. The highest mountains are 1,177 m. and 1,091 m., respectively. The main settlement of this micro-region is Srbica (Albanized as Skenderaj). The Albanian speaking Drenica Valley’s population today is to a great extent of the Serb origin but extremely pro-Albanian nationalistic. The 1998‒1999 Kosovo War started exactly in this valley as an anti-terroristic operation against the Albanian terrorists led by Adem Jashari from the village of Prekaz. Warlord Adem Jashari was pacified on March 7th, 1998 after a three-day shootout with regular security forces of Serbia that surrounded his home in Prekaz in the Drenica Valley as a part of an anti-terroristic action. During this war, for the first time in history, the Albanian nationalists and terrorists coined a new term – East Kosovo (Alb. Kosova Lindore) referring to Serbia’s region of the Preševo Valley [Elsie R., Historical Dictionary of Kosova, Lanham, Maryland‒Toronto‒Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2004] which became gradually populated by the Albanians after WWII. The Drenica Valley is a birthplace (the village of Buroja) of a former Crypto-Christian of the Serb origin – Hashim Taçi (born on April 24th, 1968) who was during the 1998‒1999 Kosovo War a commander of a terrorist organization the Kosovo Liberation Army (the KLA or in the Albanian language the UÇK).

[23] Цвијић Ј., Основе за географију и геологију Македоније и Старе Србије, књ. III, Београд: 1911, 1162−1166.

[24] According to the report from the very end of the 19th century, in the Drenica Valley in KosMet every male from 15 years of age had a rifle with himself wherever he was going. The guns were the most valuable things in society [Станковић П. Т., Путне белешке по Старој Србији 1871−1898, Beograd, 1910, 126−128].

[25] About the position of women in the Islamic societies, see in [Mohanty T. Ch., Russo A., Torres L., Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism, Bloomington−Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991, 237−270].

[26] Durham M. E., High Albania, London, 1909.

[27] In a Muslim society, term tomboy would be inappropriate.

[28] See, for instance, a Yugoslav feature movie Virdžina made in 1991 by Centar film and directed by Srđan Karanović. The movie was awarded in Berlin and Valencia.

[29] As a matter of historical fact, during the Habsburg-Ottoman peace negotiations in 1699 for the coming the Treaty of Karlowitz (today Sremski Karlovci in North Serbia) which ended the 1683−1699 Great Vienna War, the Serbian Patriarch Arsenije Crnojević sent a request to the Ottoman Sultan to be allowed to return to KosMet with his people but the request was rejected [Malcolm N. Kosovo: A Short History, New York: HarperPerennial, 1999, 163−164].

[30] Самарџић Р. и други, Косово и Метохија у српској историји, Београд: Српска књижевна задруга, 1989, 143−169

[31] Hobbes Th., Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, Wisehouse Classics – Sweden, 2016; Cooper W. K., Thomas Hobbes and the Natural Law, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018.

[32] On Tito’s Yugoslavia up to 1954, see in [Драгнић Н. А., Титова обећана земља Југославија, Београд: Задужбина Студеница−Чигоја штампа, 2004].

[33] On the Communist Albania, see in [Prifti R. P., Socialist Albania since 1944. Domestic and Foreign Developments, Cambridge, Mass., 1978].

[34] On marriage, see in [Russel B., Marriage and Morals, New York: Liveright, 1970].

[35] On this issue, see in [Pines M. A., Romantic Jealousy: Causes, Symptoms, Cures, New York−London: Routledge, 1998].

[36] Бартл, П., Албанци од средњег века до данас, Београд: CLIO, 2001, 58.

[37] The central part of Serbia, the core of the modern state, geographically, historically and ethnically.

[38] The Croatian counterpart of Šumadija.

[39] Raiders, those, who jump in.

[40] It has to be mentioned that the Greeks had their armatolies, as the counterpart of the Slavic hayduks, who had a national reputation of freedom fighters too. In the Bulgarian case, they were called the comits.

[41] The official translation into the English language is The Mountain Wreath. Gorski vijenac was written in the Serb language and published in Vienna in 1847. See [Петровић-Његош П., Горски вијенац, Беч: 1847; Костић М. Л., Сабрана дела. Четврти том: Његош и Српство, Београд: ЗИПС, 2000].

[42] A common phenomenon in all Dinaric regions populated by the highlanders but practically absent among the lowlanders.

[43] The common (pejorative) name of all Slavonic-speaking people who accepted Islam but in particular those who did it for the very opportunistic reasons.

[44] About the uskoks, see more in [Bracewell W. C., The Uskoks of Senj: Piracy, Banditry, and Holy War in the Sixteenth-Century Adriatic, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 2010].

[45] Some people even know the poem by heart, as the case with the most famous of all Dinaroids, Nikola Tesla, was.

[46] We note here that in all probability Troy was a pirate city and that this piracy was the cause of all-Greek massive assault on Priam’s town, with Hellene as an allegorical substitute of robbed goods and money, possibly as a tax. See [Lattimore R. (translator), The Iliad of Homer, London−The University of Chicago Press, 2011].

[47] See, for instance, a general history of the Ottoman Empire [Hammer von J., Historija Turskog/Osmanskog Carstva, I−III, Zagreb: Nerkez Smailagić, 1979].

[48] See, for instance [Чупић М., Отета земља: Косово и Метохија (злочини, прогони, отпори…), Београд: Нолит, 2006].

[49] This kingdom was renamed in 1929 into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. About history of the interwar Yugoslavia, see in [Petranović B., Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988. Prva knjiga: Kraljevina Jugoslavija 1914−1941, Beograd: Nolit, 1988].

[50] See: Гаћиновић Ђ. Р., Насиље у Југославији, Београд: ЕВРО, 2002, 111−133.

[51] A Turkish transliteration of Moses, commonly used in Serbia for naming bulls.

[52] Kesedžija in the Serbian language means purse (bag) cutter or simply highwayman (robber, bandit).

[53] On the First Serbian Uprising against the Ottoman authority, see in [Ђорђевић Р. М., Србија у устанку 1804−1813., Београд: Рад, 1979].

[54] Ћоровић В., Историја Срба, Београд: БИГЗ, 1993, 661.

[55] The Arabic for outlaw (pron. hidouc). The Turkish haydud, haydut (highwayman). The Hungarian hayduk, plural of haydu (soldier).

[56] “Black George” in the English language. The nickname speaks about his character for himself. Contrary to popular belief, there were Serbs who gave him this epithet, but not the Turks. See his biography in the context of historical events of the First Serbian Uprising (1804−1813): Љушић Р., Вожд Карађорђе, 1, Смедеревска Паланка: ИнвестЕкспорт, 1993; Љушић Р., Вожд Карађорђе, 2, Београд−Горњи Милановац: Војна књига, 1995.

[57] The term Rilindja means in the Albanian language “Renaissance” or “rebirth”. It historically refers to the Albanian movement from 1878 to 1912 of national awakening and revival. It covered the period from the First Albanian League of Prizren to the proclamation of the first national state of the Albanians on November 28th, 1912 during the First Balkan War (1912‒1913) [Elsie R., Historical Dictionary of Kosova, Lanham, Maryland‒Toronto‒Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2004, 154]. The movement was struggling for the creation of a Greater Albania. In 1913, at the conference of European Great Powers (the UK, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, France, and Italy) Albania’s formal independence was recognized. On this occasion, historical Serbia’s region of Kosovo-Metochia returned to Serbia, and North Epirus was given to Greece [Waldman C., Mason C., Encyclopedia of European Peoples, Volume I (A to K), New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2006, 15]. Albania’s total area is 11,100 square miles. About 70% of its territory is mountainous, and the fertile Adriatic coast comprises the other 30%. In the extremely mountainous terrain of the north lie the Dinaric Alps. In essence, Albania’s rugged terrain has isolated the country from the neighbors which enabled the preservation of its traditional and conservative culture. About 70% of the population are the Muslims, 20% are the Christian Orthodox, and 10% are the Roman Catholics. As a matter of historical fact, Albania was from 1967 to 1990 the first officially atheist country in the world as the Communist Government banned all religions. On Albania, see more in [Hall D., Albania and Albanians: Albania into the 21st Century, London: Pinter, 1994]. On the modern history of the Albanians, see in [Vickers M., The Albanians: A Modern History, New York: St. Martin’s 1995]. On the Albanian religion and culture, see in [Elsie R., A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture, New York: New York University Press, 2000].

[58] Ethnic cleansing means “the forcible expulsion or extermination of ‘alien’ peoples; often used as a euphemism for genocide” [Heywood A., Politics, Third Edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, 118]. On the theoretical background of ethnic cleansing, see in [Tesser M. L., Ethnic Cleansing and the European Union: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Security, Memory and Ethnography, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, 3‒51].

[59] To a much lesser extent, there is a similar effect with Vojvodina’s Hungarians just in different historical circumstances.

[60] From the legal point of view, the term “minority” means “the state of being an infant (or minor)” [Law J., Martin A. E., A Dictionary of Law, Seventh Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 353].

[61] Note that this is not a value judgment with regard to the Palestinian cause and Israeli-Palestinian relations. On the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, see in [Caplan N., The Israel-Palestine Conflict, Chichester, West Sussex, the UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010; Gelvin L. J., The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War, Third Edition, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Harms G., Ferry M. T., The Palestine-Israel Conflict: A Basic Introduction, Fourth Edition, London: Pluto Press, 2017].

[62] Hitler, in fact, derived his antisemitism from the Christianity [Weikart R., Hitler’s Religion: The Twisted Beliefs that Drove the Third Reich, Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, 2016, 147‒172].

[63] It was since 1965 that the Yugoslavs got the right to possess the passports and could travel abroad.

[64] In this matter, Noel Malcolm is probably the best example. But who is he? Noel Malcolm (born in 1956) is a British scholar and historian. After the success in the West of his pro-Muslim and pro-Croat book Bosnia: A Short History (London, 1995), he published next piece of shameful propaganda work ‒ pro-Albanian and enormously anti-Serbian Kosovo: A Short History (New York, 1998). This not academic, not objective and highly politically motivated book, however, was very much praised in the West and had a great impact among the Western readers during the 1998‒1999 Kosovo War. He became active pro-Albanian propagator as the president of the Anglo-Albanian Association in London.

[65] About another side of the truth upon the KosMet issue from the Western perspective, see in [Pean P., Fontenelle S., Kosovo une guerre “juste” pour créer un etat mafieux, Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2013].

[66] About ethnography and geography of High Albania see traveling records by Edit Durham. Mary Edit Durham (1863‒1944) was a British traveler and writer from a large and prosperous middle-class family from the northern region of London. She started to travel at the age of 37, set off in 1900 with a female companion on a cruise down the Adriatic seacoast, where, after spending some time in present-day Montenegro, she became fascinated with the Balkans. After returning home, Edit Durham started to study a Serb language, history of the Serbs, Serbia, and the Balkans. She traveled through Serbia for the sake to collect material for her first book, Through the Lands of the Serbs (London, 1904). At that time, she briefly visited and the Ottoman region of Kosovo-Metochia becoming acquainted with both the Serbs and the Albanians, their culture, traditions, and customs. She soon became most interested in the Albanian history, culture, and language and, therefore, she traveled in 1908 through Albania’s Highlands – a famous journey which she described in her most delightful and widely read the book, High Albania (London, 1909). This book is probably the best English-language book ever written on Albania. The book contains among other fascinating descriptions her first visiting of Kosovo-Metochia (at that time part of the Ottoman Empire). Edith Durham visited Albania for the last time in 1921 as after that she was not able to travel any more for the health reasons. However, she for the next twenty years continued to propagate on the Albanian behalf being the founding member of the Anglo-Albanian Association and writing many press articles and “letters to the editor”. Her home in London became a meeting point for friends of Albania and the Albanians in exile. In both Kosovo-Metochia and Albania today many towns have a Miss Durham Street.

[67] About the KLA from a very Western pro-Albanian perspective, see, for instance, in [Perrit H. H. Jr., Kosovo Liberation Army: The Inside Story of an Insurgency, Champaigh: University of Illinois Press, 2008; Pettifer J., The Kosova Liberation Army: Underground War to Balkan Insurgency, 1948−2001, London: C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 2012].

[68] On A. Ranković’s biography, see in [Kesar J., Somić P., Oproštaj bez milosti – Leka Aleksandar Ranković, Beograd: Akvarijus, 1990]. See his autobiography [Александар Ранковић, Дневничке забелешке, Београд: Југословенска књига, 2001].

[69] Бартл, П., Албанци од средњег века до данас, Београд: CLIO, 2001, 58.

[70] Gornji means upper in the Serbian language. There is another adjacent village, Donji (lower) Prekaz.

[71] About the real life in KosMet in Tito’s Yugoslavia, see in [Дамњановић Ј., Косовска голгота, Политика Intervju, специјално издање, Београд, 1988-10-22].

[72] The University of Ljubljana was excluded for the language barrier, although not totally.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.