Views: 1951

Preface

After the end of the USSR in 1991, Russia, at that time both weakened and isolated, was becoming a less popular area of investigation and studies compared with the period during the Cold War. However, since the year of 2004, Russia is “back” in the global political arena when Moscow rejected the European Neighboring Policy’s game with the European Union (the EU). Those who argued that Russia was already irrelevant in global politics since 2004 had to realize their error of judgment. Today, Russia is “back” as a military, economic, and political Great Power with tremendous energy resources.[1] Recovering Russia’s global power, in fact, started with a self-confidence policy by Moscow toward the EU and its bureaucratic apparatus in Brussels. Nevertheless, the EU is still one of the focal strategic partners to Russia and vice versa.

The EU’s eastern policy and Russia

The EU’s eastward enlargement in 2004 brought inside the EU eight states which had before 1991 been under the influence of the Soviet bloc during the Cold War or being the Soviet republics (the Baltic States). The planned future enlargement of the EU can increase even more this number further. These states are already ensuring that Brussels is more involved in the politics of its eastern flank bordering Russia than before, as, for instance, it was clearly demonstrated by the EU’s blatant intervention in the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election and especially in 2014 political crisis in this country.

The Russian Federation and the EU are major partners in is key spheres, including economy, energy, internal and external aspects of security. In principle, there is a strategic partnership between the EU and Russia.[2] In 2004, the relations of the EU with neighboring states were brought together under the European Neighboring Policy which formal goals were to share the potential benefits of the 2004 eastward enlargement with neighboring countries without offering formal perspective of the EU’s membership, and at such a way to prevent the emergence of stark dividing lines between the EU Member States and non-EU’s states, and to build security in the area surrounding the EU in the East by preventing significant influence of Russia in those countries. The project originally covered Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova. The European Neighborhood Policy was especially oriented toward Belarus – a country that is closely tied to the Russian Federation.[3] However, it did not cover Russia, although it has been agreed between Brussels and Moscow that their mutual relations will be developed inconsistency with the project. In other words, the EU wanted to involve Russia since 2004 into the partnership of the European Neighborhood Policy[4] but, however, Russia rejected this proposal as this policy was clearly seen as, in fact, anti-Russian and geopolitically pro-NATO/USA.[5] The EU, therefore, started to develop a strategic partnership with Russia that leads to cooperation in several important security fields like international terrorism, international crime, and the reduction and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. In other words, through the European Neighborhood Policy, one set of policies and priorities is established for non-Member States constituting West Soviet successor states, along with states in the Mediterranean basin and North Africa. In parallel, Brussels continued to develop the EU’s relations with Russia founded on the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, which was signed in 2004 and went into effect on December 1997.[6] The agreement was further augmented by the Four Common Spaces and the associated Roadmaps.

Belarus is, in fact, a very ambiguous case in the EU-Russia relationships after the end of the Cold War, but especially since the 2004 EU’s enlargement. Belarus was initially identified by Brussels to be covered by the European Neighborhood Policy, but the country soon became not eligible for participation in this program because of the EU’s formal and politically-colored objections to human rights and alleged authoritarian political practices by Belarus’ President. As a result, economic sanctions and restrictions on the travel of Belarus political leaders to the EU have been introduced and the EU’s support was primarily directed to provoke a new colored revolution in Belarus under the propaganda of the promotion of civil society and liberal democracy. However, the EU’s announcement in 2009 of the inclusion of Belarus in the Eastern Partnership followed by Brussels’ lifting of economic sanctions evoked strong objections from Moscow as Russia is seeing Belarus as a part of its sphere of influence out of those by the NATO and the EU.

On one hand, the official government position in Minsk emphasizes the country’s policy of pursuing a good political and economic relations with both the EU and Russia[7]

Placing all the European non-EU’s Soviet successor states in one basket along with a group of non-European states, the European Neighborhood Policy had several features that made it difficult for Russia to accede to when it was initiated after the May 2004 enlargement of the EU as it was suggesting that the EU may have misunderstood Russia’s agenda in proposing its inclusion in the policy for, at least, three crucial reasons:

- The initiative was formulated unilaterally by Brussels and, therefore, Russia was an object of the policy rather than coauthor of a joint strategy to stabilize the EU’s newly formed eastern frontiers.

- The bilateral nature of the European Neighborhood Policy did not suggest a regional approach that Russia would help to share in the future.

- Russia was unsatisfied about being put in the same category as states clearly having lesser power and status in the region.

Concerning the EU’s eastern policy with regard to relations with Russia, an alternative approach can be the creation of a regional and multilateral framework for the sake of stabilization and development of non-EU’s East Europe to be drafted in consultation with Russia and other regional states. However, such an approach was not seriously taken into consideration by Brussels and it likely would have been unacceptable to the majority of new Member States on the front line of the EU-Russia border especially taking into consideration the Baltic States followed by Poland. Nevertheless, such a proposal could be understood as making states like Moldova or Ukraine the objects of the joint EU-Russia machinations which are going in this case to be the dominant actors and it can be seen as sacrificing the sovereign rights of these and all other post-Soviet states to express their political destinies. However, once the European Neighborhood Policy had been announced by Brussels, it would have been difficult to retract or reframe it in the face of Russia’s rejection. In essence, both Russian and the EU’s positions looked reasonable and both are reflecting different understandings of their interests and national priorities. The result can be a policy toward perception of the so-called “Zero-Sum” game[8] between the EU and Russia in the space of Russia’s near abroad.

There are four focal points of the EU’s eastern policy in relations with Russia since 2004:

- The possibility of future EU’s membership of Russia is not taken at all into consideration as neither the European Neighborhood Policy nor the strategic partnership policy with Russia foresees future EU’s membership. There is no EU Member State advocating the EU’s membership of Russia differently to the cases of Moldova and Ukraine.

- The European Neighborhood Policy directly includes the notion of conditionality, whereas the strategic partnership with Moscow sidesteps the issue. Russia clearly rejected the conditionality policy by Brussels as non-appropriate to one Great Power as Russia is. Nevertheless, Brussels did not abandon conditionality in its relations with Russia but, contrary, imposed since 2014 non-functional sanctions against Russia because of the Ukrainian crisis and the Crimean Question supporting the anti-Russian neo-Nazi-Fascist regime in Kyiv (like in Croatia in the 1990s).

- The European Neighborhood Policy on one hand explicitly posting joint ownership of the policy with the target countries, in fact, on other hand involves a clearly asymmetrical power relationship based on the fact that the EU defines the framework for partnerships and provides at the same time funding to the states within the program of the European Neighborhood Policy. However, the relations between Russia and the EU are based on an assumption of the equality of power that is very much reinforced by energy dependence on Russia by many of the EU’s countries. For Russia, to accept convergence on some matters can be possible under certain conditions while the terms of the partnership are a matter of negotiation.

- The European Neighborhood Policy explicitly seeks to “Europeanize” the Eastern Member States and other partner countries what practically means to impose on those countries West European values, norms, regulations and interests promoted by Brussels. However, in its relations with the EU, Moscow clearly is accentuating the focal significance of Russian national interest that is a position accepted by the overwhelming majority of Russia’s population.[9]

The implications of Russia’s self-confidence in rejecting the European Neighborhood Policy in 2004 was long-lasting and profound and primarily founded on Moscow’s own preferences considering Russia’s national interest. One of the focal tasks of Russian policy toward the EU’s sponsored European Neighborhood Policy is an intention on preventing Berlin from its imperial tradition and tutoring Central and East European states from both political and economic viewpoints transforming this part of Europe into the new Mitteleuropa to be dominated by Berlin and new German (Fourth) Reich in the form of the EU.[10]

It is obvious that the EU’s strategic relationship with Russia cannot follow the practice of the European Neighborhood Policy at least for the fundamental reason because Moscow objected to those both principles and their practical implementation. Therefore, Brussels is forced to find out a new model of modus vivendi in its policy towards Russia, being unable to seek effective guidance from experience of dealing with other East European countries. That Russia is totally different case in comparison with all other cases clearly is telling the fact that Brussels has strategic partnership agreements with third countries (Brazil, Canada, China, Japan, Mexico, USA or the Republic of South Africa) but none of them is similar to the relationship with Russia which is the only strategic partner which borders the EU’s Member States.

The EU-Russia tensions

The real political tensions between the EU and Russia emerged at the time of the Georgian conflict in August 2008 as the EU as the US’ client organization followed anti-Russian policy and discourse dictated by Washington. The tensions became deeper with the Russian-Ukraine gas disputes in December 2008 and January 2009. In both cases, the EU has played an extremely important role in fueling the tensions between these states what finally opened the eyes of Moscow about the real nature of the EU in international relations.[11] This Russia’s sense of non-confidence in the EU became stronger for the reason that Brussels openly fueled growing concern of several Central and East European states about the renewed self-confidence of Russia. Poland, the Czech Republic, and Romania took part in the American sponsored and funded missile shield, which officially is designed to protect this part of Europe against potential nuclear strikes by North Korea and Iran but, in fact, the program is directed against Russia which became very furious of the US’ policy in deploying interception missiles close to the border with Russia as they can reach Russian territory easily.

Another issue of tensions between Western creations of the EU and NATO is NATO’s membership of Central and Southeast European countries or NATO’s eastward enlargement. Respective support of Washington to the intensions of Georgia and Ukraine to join NATO has created an additional set of tensions with Russia and, therefore, the Partnership for Peace arrangement as a forum to integrate Russia in the European security and cooperation framework failed. The EU exposed its concern about Kaliningrad region of Russia which became for a while a matter of controversy in Russia-EU relations but undoubtedly deteriorated them.[12] Nevertheless, the culmination of the deterioration of the bilateral relations between the EU and Russia arrived in 2014 with Brussels open support of political overthrowing of the legal President from the street by the mob of protesters in the country which is “the cradle of Russian orthodox faith and civilization”, as Russian President Vladimir Putin clearly noticed in his public speech delivered on March 18th, 2014[13] after Crimea was returned back to its homeland from Ukraine.

Up today, the gas issue is the most sensitive economic segment of the strategic partnership between the EU and Russia. The EU was deepening its links with Russia in terms of energy supply – a policy that already created certain dependency of the EU on oil and as from Russia. As Russia addressed its own issues of economic and social reforms followed by foreign policy problems, it may seek to develop its relationship with the EU as a potential alternative to the USA in the future. Russian policy on the Kyoto Protocol and on Iranian nuclear energy and weapons technology indicated the real possibilities going in this direction. When Russia cut off gas supplies in January 2009 due to Ukraine’s policy of gas-banditry, many countries in Central Europe and West Balkans were not able to get any gas in below-freezing temperatures. The EU was keen at that time to emphasize the importance of being a reliable partner and fulfilling contractual obligations as the gas dispute between Ukraine and Russia was solved by the EU’s sponsored the Gas Coordination Group that was formed in 2006 to deal with such problems. As a result, the Gas Coordination Group will monitor the transfer of gas from Russia to Europe via Ukraine.[14] Relations between the EU and Russia are going to be important for Brussels in terms of internal, near abroad (eastern), and global politics. However, the crucial question in this matter is: Will relations with the USA and/or Russia oblige the EU to deepen its foreign and security policy capacities?[15]

Ethnic Russian minority question

The position of the ethnic Russian minority in the three EU’s Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania is another problematic issue on the relations between Brussels and Moscow. As a matter of fact, the vast majority of the populations of Central, East and South East Europe are continuing the policy of assimilation of their ethnocultural minorities but in their struggle to become the EU’s Member States these countries were and are obliged to realize a required set of criteria related to the human rights and minority protection.[16] However, the biggest number of problems are still in the Baltic States, especially in Estonia and Latvia, which has the large Russian minorities and, therefore, there are periodic tensions with Russia about the Russian-speaking populations with those countries. In Latvia and Estonia in particular, the crucial problem was the sensitive issue of the official citizenship policy which is by many foreign researchers and the NGO’s observers considered as non-democratic. In the case of all three Baltic States, most parties in the coalition are right of center and are defined against the Russian minority and Russia in general (in the case of Lithuania in addition to the Polish minority as well). On the left side of political arena in the Baltic States, here are several political parties or movements which are representing the Russian speakers, but, however, they are by different technics put on the margins of political system or, in other words, they are out from mainstream politics.[17] As a crux of the matter, the EU is, in fact, protecting such minority policy that is more complicating its relations with Russia.

The exclusion of the Russian speakers who did not learn either Estonian or Latvian led to significant social and political tensions in these two Baltic countries.[18] Nevertheless, Lithuania adopted different citizenship policy only for the reason that the Russian minority in the country is not so numerous (6,3%).[19] Such tensions are for almost thirty years continuing to determine the political situation in both countries and relations with neighboring Russian Federation. A more tolerant approach was chosen by Lithuania, but in spite of that, tension with Russia has continued to shape the bilateral relations, particularly in relation to extremely high Russophobic rhetoric by Lithuanian officials. Nevertheless, Lithuanian Constitution is, in fact, blocking possibility that non-ethnic Lithuanians can be elected for the post of the President (Article 78).[20] In Latvia and Estonia the party systems are right-center, with most left-wing parties being under the domination by the large Russian-speaking groups (25% in each). Generally, it exists a sharp cleavage line between left and right political parties and movements, which coincides with ethnic division between the Russian speakers and the Latvian and Estonian populations on the opposite sides. Most Estonian and Latvian political parties support very tough language policy by their Governments towards the Russians who do not speak the official (state’s) languages (or languages in public use).[21]

The energy relationship

The pragmatic dimension of the relationship between the EU and the Russian Federation is within the framework of the energy relations which includes three focal issues. Nevertheless, both partners lack legally binding instruments to direct their pragmatic energy relationship. Negotiations between these partners appeared to be extremely difficult taking into consideration a deteriorated global geopolitical climate which is lacking constructive both ideas and tools for organizing the Post-Cold War global arena.

The three focal issues in the EU-Russia energy relationship are:

- The Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (the PCA) of 1994.

- The Energy Charter Treaty (the EChT).

- The Energy Dialogue (the ED).

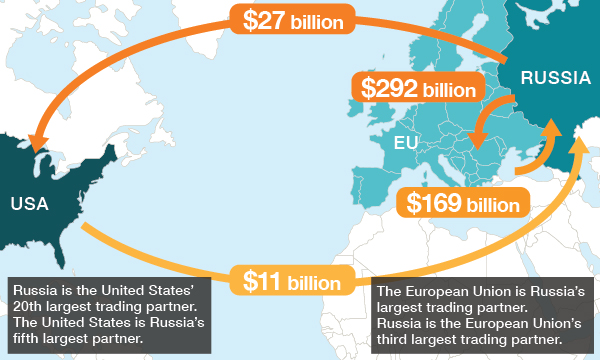

In recent years, Russia became the third trade partner of the EU after the US and China. The energy relationship between Russia and the EU is very much trade relationship in regard to oil, but particularly gas. More than half of Russian foreign trade turnover and two-thirds of cumulative foreign investments in Russian economy fall to the EU’s share. The EU is the main importer of Russian energy resources, and Russia firmly holds the position of the biggest supplier of natural gas to the EU, satisfying the overall demand for it in the EU Member States by a quarter, and remains the second most important exporter of crude oil and oil products to the EU.[22] There are many debates in the mass media as well as academic circles is Russia as an energy power misuses or might use in the future its energy weapon against the EU? As a matter of fact, both the 2004 and 2007 EU accessions of the countries coming from the ex-Soviet bloc increased sensitivity on the EU’s existing overdependence on Russian energy sources. Political conflicts between Russia and other ex-Soviet republics (especially Lithuania) are continuing, with energy being an important card in the Russian hands taking into consideration the fact that gas trade ties together Russia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and the EU.[23] However, the crux of the matter is that up to now there is no satisfying answer given to the question of how infrastructures created in the Soviet time can be reconstructed and adapted to a totally changed geopolitical arena after the Cold War.

Reciprocal investments in the energy sector are up to now limited for the very reason of the regulatory issue, but as well as due to preventive measures like the “third country clause” which Brussels included in its legal position. This clause clearly is targeting Russian biggest gas-supplier and exporter Gazprom and, therefore, it is unofficially called “Gazprom Clause”. In addition, electricity interconnection, although being under discussion, is so far nonexistent, for two reasons: technical and political. The EU’s external energy policy is only at an early stage of development and it gains importance usually at the time of energy crisis. It is put under the competence of the Member States and naturally the gigger Member State, the more it will try to organize relations with Russia on bilateral basis (like Italy, France or Germany); the smaller a state is, it will try to rely on the EU’s instruments, and force the others to act as a group as the example of newly accepted Member States from the East (since 2004) it shows clearly.

Cooperation between Russia and the EU progressively strengthens in foreign policy and security issues, in combating illegal migration, organized crime, and international terrorism. The full potential of Russia-EU interaction in these and other spheres is still to be realized, but the main achievement of recent years, which can be hardly overestimated, is the understanding increasingly gaining ground that partnership between Russia and the EU is one of the cornerstones of maintaining stability and prosperity not only in Europe but worldwide as well. Joint responsibility for finding responses to present-day challenges as well as solid and mainly positive foundations of traditional, sometimes centuries-old relations with individual EU’ Member States, common principles and ideals of European civilization, similarity of their historical destinies – all this is shaping a genuinely strategic character of the EU-Russia’s relationship.

The Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (the PCA) was ratified in 1997 with entering into force in 1999. It was originally set up to enhance the political dialogue between the EU and Russia, and soon it was followed by similar agreements with eleven other ex-Soviet Union Republics.[24] Nevertheless, the primary task of this agreement was to promote democracy, trade, and convergence: the energy issue is delt only with Article 65, and indirectly in Article 12 refers to the freedom of transit. New negotiations occurred in July 2008 but have been soon suspended by Brussels next month due to the Georgia-Russia War for several months (resumed in 2009). The main issues of the negotiations were: the amount of and terms of buying, shipping,, and marketing of natural gas, oil, and electricity. However, in reality, deteriorated diplomatic and political relations followed by the bilateral lack of trust and opposing concepts of such arrangements like the Energy Charter, continue up today to handicap the negotiations.

The Energy Charter Treaty (the EChT) is transferring energy-related questions between the EU and Russia to the legal framework of the PCA. During the last 15 years, several attempts were made in order to find a solution to the lack of the EU-Russia legal framework. The EChT was imagined as an umbrella for dialogue and cooperation on energy between the EU and Russia. It is schemed to improve investment security for the producers and supply security for the consumers. However,its weakness is in the very fact that producers countries Russia and Norway never ratified it, while the countries that ratified the Charter, like Ukraine for example, did not respect the rules of the agreement.[25] Therefore, the EChT never was functioning properly due to the fact that it was not ratified by two focal energy producers and suppliers – Russia and Norway. In essence, defining the rules of the energy game of interdependence is the crucial requirement in the EU-Russia energy relations.[26]

The EU-Russia Energy Dialogue (the ED) was adopted in the year of 2000 and it was set up to compensate for the absence of cooperation within the EChT. The EChT is not legally binding, but rather it constitutes a permanent consultive mechanism. There were four issues for discussion of common bilateral interest put forward on agenda:

- Security of supply.

- Investment in the Russian energy sector.

- Climate change.

- Nuclear energy.[27]

With regard to the EU’s and Russia’s legislation, there are two focal developments:

- For the EU: The adoption of the third package and the Lisbon Treaty, including an energy paragraph.

- For Russia: The two federal laws of the Russian Federation of April 2008 amending the foreign investment regime in the strategic sector of Russia’s economy, including energy as well.[28]

Obviously, all of these measures reflect a high degree of bilateral distrust and constitute additional obstacles to mutual investments and cooperation in the energy sector. The EU is clearly a weak actor in this field concerning the partnership with Russia.[29]

Formats of cooperation

The history of official relations between Moscow and Brussels counts 30 years. The very first document regulating the relations between at that time the Soviet Union and later Russia as its successor state and the EU was the Agreement on Trade and Commercial and Economic Cooperation between the USSR, on one hand, and the European Community (from 1993 the European Union), on another, signed on December 18th, 1989. At that time, it was only about the establishment of cooperation. The Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, signed four and a half years later, on June 24th, 1994, became a significant step forward as it provided the foundation for the development of enhanced relations in the political sphere, trade, and economy, in legal and humanitarian areas. The next milestone in Russia’s relations with the EU was the endorsement at the Summit in St. Petersburg in May 2003 of the concept of four Common Spaces: Common Economic Space, Common Space of Freedom, Security and Justice, Common Space of External Security, and Common Space of Research and Education, including Cultural Aspects. The implementation of the so-called Roadmaps for these Common spaces, adopted at the Summit in Moscow in May 2005, remains a key track of interaction between Russia and the EU.[30] At their Summit in London in October 2005 Russia and the EU stated the necessity to renew the legal foundation, which was no longer matching the ambition of creating the four Common Spaces and in general no longer reflected the level of cooperation achieved. At the following Summit in Sochi in May 2006, the parties reached a political agreement to start work on a new basic document, aimed at filling with additional specific substance the very idea of the strategic partnership and establishing effective mechanisms of its implementation. Negotiations on the future agreement started in 2008 and have been continued.

The relationship between Russia and the EU is supported by a well-established institutional architecture that enables the two sides to discuss at different levels practically all problems of today’s world. The existing formats of the Russia-EU cooperation include:

- Summits with the participation of the President of the Russian Federation, on one hand, and the Presidents of the European Council and the European Commission, on another.

- Meetings between the Russian Government and the European Commission.

- Sessions of the Permanent Partnership Council at Foreign Ministers’ level and in other specific sectoral configurations (including justice and home affairs, energy, transport, science, and technologies, etc.).

- Meetings at Political Directors’ level.

- Regular meetings between the Permanent Representative of Russia to the EU and the Chairman of the EU Political and Security Committee.

Interaction intensified in the format of sectoral dialogues (including in such fields as energy, transport, industrial policy, information society, space) and expert consultations on foreign policy issues (more than 20 meetings per year). Meetings between members of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation and the European Parliament have been taking place on a regular basis. Specific tasks for the nearest future aimed at strengthening the strategic partnership between Russia and the EU are determined by the very logic of development of relations with the EU. They include transition to a visa-free regime, the establishment of more effective and result-oriented interaction in the sphere of foreign policy, crisis management, and launch of a dialogue on the “coupling” of concepts of economic and social development in Russia and the EU until 2020.

In the context of overcoming the negative impact of the global financial and economic crisis which started in 2008, the initiative, endorsed at the 25th Russia-EU Summit in Rostov-on-Don on May 31st, −June 1st, 2010, to establish a Russia-EU Partnership for Modernization acquired special significance. This partnership was designed to serve as a flexible framework for promoting reform, enhancing growth and raising competitiveness in Russia and the EU. Its priority areas include expanding opportunities for investment in innovation, enhancing and deepening bilateral trade and economic relations, promoting alignment of technical regulations and standards, advancing sustainable low-carbon economy and energy efficiency, enhancing cooperation in innovation and research, promoting people-to-people links, and enhancing dialogue with civil society and the business community. At the 26th Russia-EU Summit in Brussels on December 7th, 2010 both sides launched a Rolling Work Plan for activities within the Partnership for Modernization.

Following the political and economic recovery presided by Putin and administrated by Medvedev, Russia has emerged in the role of norm transmitter, challenging not just the US but also the EU in their self-proclaimed mission in promoting the value of democracy and human rights worldwide. Within the framework of what has been referred to as a Greater Europe, there is unease, triggered in part by the Eurozone crisis, about the EU´s future role in global affairs and, ironically, in Europe itself. No longer is it self-evident that the EU is the moral, economic and political center of Europe; it is being increasingly challenged in this role by Russia. The norms that Russia promotes are different from those propagated by the EU such as democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The Russian standard is centered on a robust and resolute interpretation of sovereignty, national self-determination, and state’s struggle against international terrorism (in Syria, for instance). If the EU is in general decline the same may be said about the US, which is no longer uncontested global superpower. In view of its chronic economic difficulties and the conspicuous lack of political initiatives to resolve the crisis that has characterizes the administrations of Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump, the US has lost ground in relation to both Russia and China.

From what we know of the construction of Russia´s image over time, there is little doubt that perceptions of the American and the EU’s decline will diminish the centrality of images of the US and the EU in the Russian national identity construction. It seems like a conclusion, that just as Russia´s attention during the 20th century shifted from Europe to the US, in the near future China will probably replace the US as the yardstick against which Russia will measure itself. Ever since Peter the Great, Russia´s leaders have been careful to assert Russia´s belonging to Europe. On this basis alone the prospective shift in focus from Europe to Asia-Pacific represents a major challenge for the future constructions of Russia´s national interest and Russia’s role in global politics.

The EU-Russia relationship: Focal interests

Focal EU’s interests in the relationship with Russia are:

- To establish a reliable supply of gas and oil from Russia.

- To settle transit regimes of gas and oil from Russia.

- To settle the advantageous prices of the gas and oil from Russia.

- To reach independent access to the markets of Central Asia without being obliged to use the transit via Russia.

- To establish a diversification in the energy mix, particularly of the new Member States from Central Europe, for the sake to avoid supply crisis as it happened, for instance, in winter 2009.

- To fix energy efficiency in the producer countries.

Focal Russia’s interests in dealing with the EU are:

- To remain the major player in the important EU’s gas and oil market.

- To have reliable and economically beneficiary transit routs or direct infrastructure regarding the export of the gas and oil on the EU’s market.

- To have the security of demand in gas and oil in the coming decades, in order to engage in investments.

- To increase energy efficiency as flaring and transport.

- To avoid conflicts, especially with the new eastern EU’s Member States (joined the EU in 2004, 2007, and 2013), but as well as with the other former republics of the USSR.[31]

Final remarks

During the first decade after the Cold War, before Russia renewed her international and regional reputation and self-assertion under the President Vladimir Putin, many of the principles contained later in the EU’s European Neighborhood Policy have been applied in reality by Brussels to Russia at that time lead by pro-Western leadership of Boris Yeltsin and his liberal Governments. The EU-Russia relationships in the 1990s were very asymmetrical and involving the attempts of conditionality practice by Brussels followed by an effort to “Europeanize” Russia and export West European norms and values to it. However, with its rejection of the European Neighborhood Policy by the EU, Putin’s Russia demanded a turning point in the relations with Brussels in which Russia was going to be respected as an equal partner but not a subordinated client as it is the case with all Central and East European states in their relations with the EU. Nevertheless, the EU’s relationship with Russia does not have a clear trajectory, particularly taking into consideration many political irritants that have the potential to halt progress.

The gap that has emerged between Russia and the EU including particularly strong Russophobic discourse in some new Member States, has reduced the trust that may be focal for the inclusion of Russia in the space for compromise dialogue and interaction that the EU formally is trying to establish. Very much will depend primarily on domestic developments in Russia which are due to the policy of West are getting defensive patriotic tendencies since the beginning of this millennium.

As a matter of fact, Russia is since 2004 once again a major player in global politics and international affairs and her political elite will for sure not accept the treatment of Russia as a kind of subordinated or junior partner of the sort that Brussels (and Washington) envisaged in the first post-Cold War’s decade.[32]

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2019

[1] Eric Shiraev, Russian Government and Politics: Comparative Government and Politics, , 23.

[2] José M. Magone, Contemporary European Politics: A Comparative Introduction, London‒New York: Routledge, 2011, 578‒579.

[3] Michelle Cini, European Union Politics, Oxford, UK‒New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007, 438.

[4] Ian Bache, Stephen George, Politics in the European Union, Oxford‒New York, Oxford University Press, 2006, 500‒501. See more in [Ainius Lašas, European Union and NATO Expansion: Central and Eastern Europe, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010].

[5] See more in [Michael E. Smith, Europe’s Foreign and Security Policy: The Institutionalization of Cooperation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004].

[6] Roger E. Kanet (ed.), Russian Foreign Policy in the 21st Century, New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 246.

[7] Comment by Sergei Martynev, the head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Belarus in Iurii Shpakov, “Vozmozhnost otoiti ot Rossii”, Vremia novostei, No. 25, 2009-02-13.

[8] “Zero-Sum” game is a situation of pure conflict in which the gain of one political actor is equal to the loss of another [Richard W. Mansbach, Kirsten L. Taylor, Introduction to Global Politics, London, UK−New York, USA: Routledge, 2012, 586].

[9] Joan DeBardeleben (ed.), The Boundaries of EU Enlargement: Finding a Place for Neighbours, Houndmills−Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, 70−91.

[10] About the German imperial concept of Mitteleuropa, see in [Peter J. Katzenstein (ed.), Mitteleuropa Between Europe and Germany, Providence, USA−Oxford, UK: Berghahn Books, 1997]. On history of Central and East Europe, see in [Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, London−New York: Routledge, Andrew C. Janos, East Central Europe in the Modern World: The Politics of the Borderlands from Pre- to PostCommunism, Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press, 2000].

[11] On the EU in the international relations, see in [C. Piening, Global Europe: The European Union and World Affairs, Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1997; Christopher Hill, The International relations of the European Union, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005; Steve Marsh, Hans Mackenstein, The International relations of the European Union, Harlow: Pearson-Longman, 2005; Charlotte Bretherton, John Vogler, The European Union as a Global Actor, London: Routledge, 2005; Knud Erik Jørgensen, Mark A. Pollack, Ben Rosamond (eds.), Handbook of European Union Politics, London‒Thousand Oaks‒New Delhi: SAGE Publications, 2007, 505‒576].

[12] Michelle Cini, European Union Politics, Oxford, UK‒New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007, 450.

[13] Bogdan J. Góralczyk (ed.), European Union on the Global Scene: United or Irrelevant?, Warsaw: Centre for Europe, University of Warsaw, 2015, 245.

[14] European Commission, IP 09/24, 2009-01-09.

[15] Michelle Cini, European Union Politics, Oxford, UK‒New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007, 450.

[16] See more in [Yvonne Goldammer (ed.), The Long Road of Smaller Countries into the Enlarged European Union, Vilnius: Eugrimas, 2006; Peter Van Elsuwege, From Soviet Republics to EU Member States: A Legal and Political Assessment of the Baltic States’ Accession to the EU, I‒II, Leiden‒Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2008].

[17] José M. Magone, Contemporary European Politics: A Comparative Introduction, London‒New York: Routledge, 2011, 197, 468.

[18] About the question of the Russian-speaking population in Estonia, see [Jean-Jacques Subrenat (ed.), Estonia: Identity and Independence, Amsterdam‒New York, NY: Rodopi, 2004, 269‒280].

[19] Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, Lithuania. Guide, Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 2016.

[20] The Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania: https://www.lrkt.lt/en/about-the-court/legal-information/the-constitution/192

[21] See more in [Marko Lehti, David J. Smith (eds.), Post-Cold War Identity Politics: Northern and Baltic Experiences, London‒Portland, OR: Frank Cass, 2003].

[22] Roger E. Kanet (ed.), Russian Foreign Policy in the 21st Century, New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 266.

[23] See more in [Simon Pirani (ed.), Russian and CIS Gas Markets and Their Impact on Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009].

[24] See http://europa.eu on Partnership and Cooperation Agreements, 2009.

[25] Sergei Selivestov, Energy Security of Russia and the EU: Current Legal Problems, Note de l’lfri: Paris, 2009.

[26] Roger E. Kanet (ed.), Russian Foreign Policy in the 21st Century, New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 274.

[27] “EU-Russia Energy Dialogue”, EurActiv, 2006-10-22.

[28] Sergei Selivestov, Energy Security of Russia and the EU: Current Legal Problems, Note de l’lfri: Paris, 2009, 16.

[29] On the issue of Russia’s geopolitics of energy resourses, see in [Срђан Перишић, Нова геополитика Русије, Београд: Медија центар „Одбрана“, 2015, 165−182].

[30] See [Commission of the European Communities, “EU-Russia Common Space, Progress Report 2009”, 2010].

[31] Bertil Nygren, The Rebuilding of Greater Russia: Putin’s Foreign Policy Toward the CIS Countries, Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2007; Simon Pirani (ed.), Russian and CIS Gas Markets and Their Impact on Europe, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009.

[32] Timothy Garton Ash, Free World: America, Europe, and the Surprising Future of the West, New York: Random House, 2004.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]