Views: 940

“Ethnic affiliation has never been forgotten in the territories of the former Yugoslavia. It did play a certain role, and it did influence decisions even during the Tito’s era of strict ‘Brotherhood and Unity’”

[Várady T., “Minorities, Majorities, Law and Ethnicity: Reflections of the Yugoslav Case”, Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. 19, 1997, p. 42]

People, nation and state

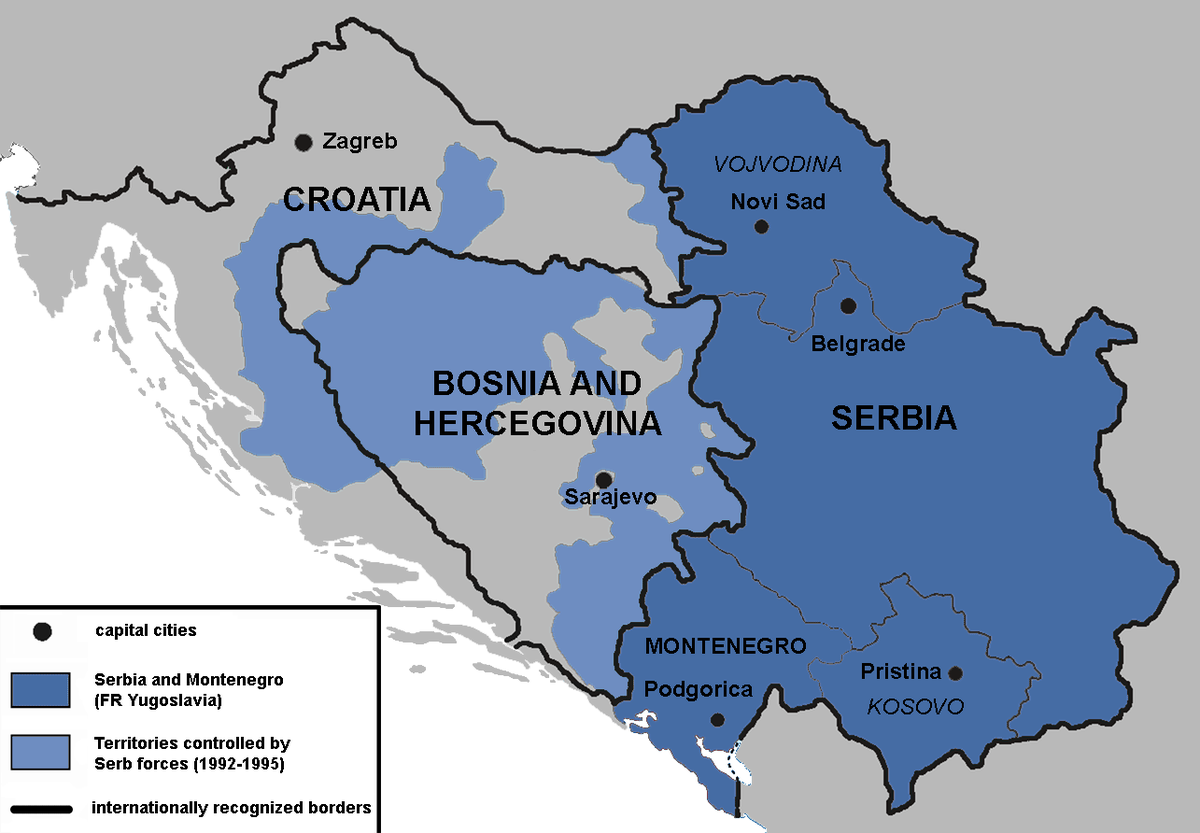

I agree that “in Yugoslavia, all political problems are intimately linked with the issue of nationalism”.[i] Indeed, the fixing of inner or administrative borders between Yugoslavia’s nations and nationalities became one of the main issues that forged nationalism after the Second World War onward and most probably in the future as well. The problem was in fact that internal borders between socialist republics and two autonomous provinces[ii] of the ex-Yugoslav federation (from 1974 to 1991 Yugoslavia was de facto confederation of eight independent political entities) were set up in 1945 and definitely delimited ten years later, but they very often did not follow historical, natural, ethnic and justice principle.[iii] The core of the puzzle became that constitutionally six federal republics and two autonomous provinces were seen as the “national” states, i.e. with the dominance of a nation or nationality, but the inner administrative borders failed in many cases to strictly separate ethnic communities. To be honest, it was impossible without exchanging the parts of national groups between republics and provinces what finally was done during the civil war of 1991−1995 and later the Kosovo War of 1998−1999 within the framework of the ethnic cleansing, i.e. the forced exchange of the population to the „proper“-side of the borders.[iv]

The first problem to be solved in this article is to define the terms of a “people”, a “nation” and a “state”. In search of definitions of terms „people“, „nation“ and „state“, it should be pointed that a “modern” state is composed by three elements: the territory, the people and the power, while older patriarchal theory of a state is based on four elements: the family, the tribe, the people, and the nation. A definition by the objective criteria of a “people” or/and a “state” in the ethnic sense takes into consideration the language, religion, history, culture, and fate: persons speaking the same language, adhering to the same religion, or with the same history, culture or fate are a people (for instance, the Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians, Albanians or Greeks). Individuals with the same characteristics form a people or a nation (the German “kulturnation”). However, according to the theory of ethnic indifference, all persons who hold the citizenship of a state, regardless of their ethnic or national origin, confessional affiliations, etc., form the people of the state (for instance, the Bosnians, Americans, Swiss people, Belgium people or Canadians).[v]

A definition through subjective criteria (favored, for instance, by Ernest Renan) points out that “a people is made up of all persons who want to live together”.[vi] Therefore, according to the theory of ethnic indifference, for example, all citizens of the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina can be one people, i.e. one nation (Bosnians), but according to subjective criteria, they can be either the Serbs, Croats or Muslims/Bosniaks.[vii] However, if we would implement in the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina the understanding of a nation in the sense of the German 19th-century Romanticist ideology (favored by Herder, Humboldt, Fichte)[viii] that the only language determines a people/nation. Therefore, we have to recognize in this case only one “ethnolinguistic” group in Bosnia-Herzegovina: the Shtokavians, i.e. the ethnolinguistic Serbs. The same case is with the so-called “Montenegrins” who are in fact the ethnolinguistic Serbs by their “ethnicity”.[ix]

The crucial question on this place is: when do a people (Greek ethnos, French ethnie) become a nation? The answer according to the nationality principle is: a nation is a people in possession of, or striving for, its own state.[x]

Yugoslav nationalism(s), state and nation

The relationship between a state and a nation is vital in the case of Yugoslav nationalism(s). At the times of Reformation, Counter-Reformation, and Baroque, the nationalism on the Yugoslav lands was shaped in accordance with the famous model of the Augsburg Religious Peace Settlement of 1555: “Cuius regio, eius religio”. However, already from the epoch of Enlightenment followed by the age of Romanticism, the nationalism among the Yugoslavs, especially among the Serbs and Croats, was modeled according to the new formula: “Cuius regio, eius lingua”.[xi] Finally, the South Slavs advocated a separation of state and ethnicity (mainly understood as ethnolinguistic people) from the mid-19th century.[xii]

The most distinguishing feature of the majority of the Yugoslav and Balkan nationalisms is that they accepted the formula: “One language–one people–one nation–one state”.[xiii] In the process of nation-state building, the Yugoslav ethnicities followed exactly the axiom created by David Miller:

“Political communities should as far as possible be organized in such a way that their members share a common national identity, which binds them together in the face of their many diverse private and group identities”.[xiv]

Like David Miller’s axiom, the saying of Ernest Gellner that nationalism is political principle according to which political unity (i.e. state) should be overlapped with national unity (i.e. nation)[xv] is quite valid for the majority of examples of the Yugoslav and Balkan nationalisms, especially for those from the 20th century – a century of ethnic cleansing, forced migrations and assimilation in the Balkans (and other parts of Europe and the world as well).[xvi]

Another significant peculiarity of Yugoslav nationalisms is that some of them (for instance, Croatian in the 19th century and Bosnian-Herzegovinian Muslim/Bosniak in the 20th century) accepted (with local modifications) the French model of ethnic indifference in state formation and nation-building. According to this state-nation model, there are three main pillars of the state-nation building process:

- Popular sovereignty: “people” = legal fiction to constitute normative principles: (individual) equality and democratic state organization.

- National sovereignty: “nation” = legal fiction to defend external independence and to discriminate internal pluralism, also in terms of ethnic difference.

- Effects: repression of pluralism through assimilation.[xvii]

In other words, all inhabitants of Croatia have to be the “Croats” and all citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina have to be the “Bosnians”. I argue that the ultimate goal of acceptance of such a model among the Yugoslavs was not to build up a kind of “civic society”, but rather to assimilate the “other” ethnonational groups for the purpose of creation of a nationally homogeneous state.[xviii]

On the other hand, instead of the French state-nation model, some of the Yugoslav nationalisms (for instance, Serbian, Albanian, Slovenian, and contemporary Croatian and Macedonian) in regard to the state creation and nation-building procedure had (has) a feature of the Central and East-European nation-state model, which had (has) the next main characteristics:[xix]

- Nationality principle: “nation” = one people + one state.

- Political function: unification for state-formation.

- The “individual” is no longer the ethnically indifferent “citoyen”, but defined by membership in a certain ethnic community.

- “Equality” relates only to members of own group.

- “Difference” of groups is translated into the majority/minority position.

- Possible effects: ethnic cleansing through expulsion from a territory, extinction.[xx]

In other words, the “nation-owner” of a state has more rights than the “nations-non-owners”. The “nations-non-owners” are in fact proclaimed, or treated, as the ethnic (national) minorities. However, it is a common Yugoslav and Balkan understanding of minorities that they are, in fact, a great source of “irredenta”, i.e. of secession.[xxi] Therefore, if one Yugoslav or Balkan country can not avoid having a minority group then the slogan “why should we be a minority in your country when you can be a minority in our” should be respected.

What concerns the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (the SFR Yugoslavia, 1945−1991), it existed the so-called “three-level system” of a national (group) rights:

- On the first level, there were six „Nations of Yugoslavia“ (the Croats, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Muslims, Serbs, and Slovenes). Each of them had their own “national” state that was one of six socialist republics in Yugoslavia.[xxii]

- On the second level, there were ten „Nationalities of Yugoslavia“ (the Albanians, Hungarians, Bulgarians, Czechs, Gypsies, Italians, Romanians, Ruthenians, Slovaks, and Turks).[xxiii]

- Finally, on the lowest, third, level there were „Other Nationalities and Ethnic Groups“ (the Austrians, Greeks, Jews, Germans, Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, Vlahs, “Yugoslavs”,[xxiv]).[xxv]

However, it has to be stressed here, that there were only three recognized constitutive nations within the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from 1918 to 1929 and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1929 to 1941: the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.[xxvi] Nevertheless, in post-war socialist Yugoslavia (Titoslavia) there were recognized six of them: the Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians, Montenegrins, and Muslims. Actually, the last three of them have been newly proclaimed nations at the expense of the Serb national corpus.

In sum, there are two types of national identity:

- Based on the “civic” criteria of grouping (France, Croatia in the 19th century, Bosnia- Herzegovina, Canada, the U.S.A., etc).

- Based on “ethnic” criteria of classifying as common blood and culture (the Serbs, Greeks, Bulgarians, Macedonians, Slovenes, Albanians, etc.).[xxvii]

In conclusion, referring to the Yugoslav case, I agree with Anthony Smith:

“By ‘nationalism’ I shall mean an ideological movement for the attainment and maintenance of autonomy, unity and identity of a human population, some of whose members conceive it to constitute an actual or potential ‘nation.’”…”A ‘nation’ in turn I shall define as a named human population sharing an historic territory, common myths[xxviii] and memories, a mass, public culture, a single economy and common rights and duties for all members”.[xxix]

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

[i] Holmes L., Politics in the Communist World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986, p. 331.

[ii] These two provinces (Vojvodina and Kosovo-Metohija) are created only within a federal unit of Serbia and had been very much politically independent from her. However, each ex-Yugoslav republics could get their autonomous provinces according to the same criteria applied in the case of Serbia which in that sense became asymmetrically federated with the rest of the country and even in the inferior position. According to the last Yugoslav Constitution of 1974, Vojvodina and Kosovo-Metohija received the same political power as all other Yugoslav republics including and the veto right in the upper house of the state Parliament (the Federal Assembly) – the Council of Republics. About the post-1945 Titoslavia and the Serbs, see in [Симић П., Тито и Срби, Књига 2 (1945−1972), Београд: Laguna, 2018].

[iii] Within such constructed (con)federal structure of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia the Republic of Serbia was the only inferior partner. An autonomous (in fact, independent) provinces have been created only on the territory of Serbia, which was politically subordinated to and economically exploited by Slovenia and Croatia – the masters of the post-Second World War Titoist Yugoslavia. The Communist political leadership of Slovenia and Croatia decided to break up with the rest of Yugoslavia only when the new Serbia’s Communist leadership started with the policy of equal partnership and cohabitation in political and economic spheres of inter-republican relationships in 1989−1990. See more in [Антић Ч., Српска историја, Четврто издање, Београд: Vukotić Media, 2019, 287−317].

[iv] Regarding the Western point of the general history of the problems of ex-Yugoslavia see [Allcock B. J., Explaining Yugoslavia, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000].

[v] Regarding the problem of ethnic identity in the contemporary world see [Guibernau M., Rex J. (eds.), The Ethnicity. Reader. Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Migration, Malden MA: Blackwell Publishers Inc., 1999].

[vi] “L’existence d’unc nation est un plébiscite de tous le jours”. E. Renan also pointed out that a nation believes to have a common origin and has to have a common enemy(ies) in order to develop a sense of group solidarity.

[vii] The “Muslims” as a distinctive ethnic group within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia were officially proclaimed by the Yugoslav authorities (i.e. by the League of Yugoslav Communists) in 1961. Official recognition of this religious group as the “Muslim nation” (predominantly living in Bosnia- Herzegovina) was done in the 1971 census. There were officially 25,69% of Muslims out of a total percentage of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s inhabitants in 1961, while according to the 1971 census there were 39,57% of them. The term “Bosniaks” (Bošnjaci) is related only to the Bosnian-Herzegovinian “Muslims”, but not to the ethnic Serbs or Croats from the same republic, while under the term “Bosnians” should be understood all citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina. However, there is a strong propaganda tendency by the local Muslims to put equality between the terms “Bosniaks” and “Bosnians”. The purpose to proclaim a “Muslim” nation in Bosnia-Herzegovina by the Yugoslav government was of pure political nature – to separate them from the ethnolinguistic Serbs. Sometime after the First World War, it was published in Vienna “Ethnographic Map of Yugoslavia” on which Bosnia-Herzegovina was described as a province populated only by the Serbs [Костић М. Л., Наука утврђује народност Б-Х муслимана, Србиње−Нови Сад: Добрица књига, 2000, p. 92]. About the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina, see [Donia R., Fine, Jr, V.A., Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed, New York: Columbia University Press, 1994; Pinson M. (ed.), The Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina: Their Historic Development from the Middle Ages to the Dissolution of Yugoslavia, Second Edition, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1996].

[viii] For instance: “weit mehr die Menschen von der Sprache gebildet werden, denn die Sprache von den Menschen” [Fichte G. J., Reden an die deutsche Nation, Berlin, 1808, p. 44]. About the ideas of the German Romanticism see [Craigi G. A., The Politics of the Unpolitical: German Writers and the Problem of Power, 1770−1871, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995; Walzel O. F., German Romanticism, New York: Capricorn Books, 1966; Beiser F., The Early Political Writings of the German Romantics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996; Beiser F, Enlightenment, Revolution, and Romanticism: The Genesis of Modern German Political Thought, 1790−1800, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992].

[ix] Carter F. W., Norris H. T. (eds.), The Changing Shape of the Balkans, London: UCL Press Limited, 1996, p. viii. The “Montenegrin” nation was officially proclaimed for the first time in history by the Yugoslav Titoist officials after the Second World War in order to separate Montenegrin Serbs from the rest of the Serbdom. By that time, the Orthodox Slavic population in Montenegro was considered as ethnic Serbs and as such, they have been declaring themselves at the censuses [Glomazić M., Etničko i nacionalno biće Crnogoraca, Beograd: TRZ „Panpublik“, 1988]. However, according to the ethnolinguistic theory of national identification, all Serbian-speaking population (the individuals whose mother speech is the Shtokavian dialect) regardless on religion are the ethnic Serbs what practically means that the Roman Catholic inhabitants around the Gulf of Boka Kotorska (south-west Montenegrin littoral close to Dalmatia) are members of the Serbian nation, likewise the Roman Catholic citizens of Dubrovnik. About the case of Dubrovnik see [Костић М. Л., Насилно присвајање дубровачке културе, Нови Сад: Добрица књига, 2000].

[x] An ethnos can be defined as a people, i.e. group of people, who have a common name, motherland, historical memory, culture and sense of solidarity. A nation can be described as ethnos that lives in its national state organization or seeks to create such an organization. See [Hroch M., “From national movement to the fully-formed nation. The nation-building process in Europe”, New Left Review, № 198, 1993, pp. 3–20; Kaplan R., “The coming anarchy: how scarcity, crime, overpopulation and disease are eroding the social fabric or our planet”, Atlantic Monthly, February, 1994, pp. 44–76; Moinyhan D. P., Pandemonium, New York: Random House, 1992].

[xi] This formula is in our days present in the cases of Switzerland, Belgium, Quebec, Montenegro or Bosnia-Herzegovina.

[xii] About the debate on the language-ethnicity link in academic and in everyday-life perspective see [Conversi D. (ed.), Ethnonationalism in the Contemporary World. Walker Connor and the study of nationalism, London−New York: Routledge, 2004, pp. 83−92].

[xiii] About connections between the language and nationalism in Europe see [Blommaert J., Verschueren J., “The role of language in European national ideologies”, Pragmatics, Vol. 2, № 3, 1992, pp. 355–375; Barbour S., Carmichael C. (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000]. The Albanian protesters in Prishtina, Kosovo-Metochia, for instance, required in October 1992 restoration of the university education system in the Albanian language, but this demand was seen by the Serbian authority as an expression of Albanian separatism. It has to be remarked that today there is no university education system in the Russian language in Lithuania, Estonia or Latvia and that today, as well as, there is no any educational system in the Serbian language in Albanian ruled “Republic of Kosova” as “independent” state (self-proclaimed on February 17th, 2008). The Albanian language education is not allowed at the university level in North Macedonia, too, likewise in the Turkish language in Bulgaria or the Kurdish language in Turkey.

[xiv] Miller D., On Nationality, Oxford: Claredon Press, 1995, p. 188.

[xv] Gellner E., Nations et nationalisme, Paris: Editions Payot, 1989, p. 13.

[xvi] The contemporary “developed and advanced West”, however, is not immune on the nationalism as well, especially on the linguistic one. For instance:

“Nationalism is the will to have a particular way of being and the possibility to build up one’s own country”…”Our [Catalan] identity as a country, our will to be, and our perspectives for the future depend on the preservation of our language”…”It is task of all those who live in Catalonia to preserve its personality and strengthen its language and culture”

[Pujol J., Construir Catalunya, Barcelona: Pórtic, 1980, pp. 22, 35, 36]

or:

“If you cannot speak Welsh, you carry the mark of the Englishman with you every day. That is the unpleasant truth”

[The Guardian, November 12, 1990, p. 1]

On this issue see [D’hondt, Sigurt, Blommaert J. i Verschueren J., “Constructing Ethnicity in Discourse: The View from Below”, Martiniello M. (ed.), Migration, Citizenship, and Ethno-National Identities in the European Union, Avebury, 1995, pp. 105−119].

[xvii] Prof. Joseph Marko’s lecture: “State Formation and Nation-Building in Europe, Summer Academy 2000: “Regions and Minorities in a Greater Europe”, European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano, September 2000, Bressanone/Brixen, Italy.

[xviii] For Croatia’s case see [Крестић Ђ. В., Геноцидом до велике Хрватске, Јагодина: Гамбит, 2002]. Regarding the issue of the historical process of creation of the national identities in the Balkans see [Bianchini S., Dogo M. (eds.), The Balkans. National Identities in a Historical Perspective, Ravenna: Longo Editore Ravenna, 1998]. Differently to the case of Croatia, in Serbia never was developed or advocated the French model of ethnic indifference in a state formation process.

[xix] This model was implemented in the 19th-century building of the Italian and German nation and state. The product was Italian (1859–1866) and German (1866–1871) national unification into the single national state. This model had a direct impact on the Central, East, and South-East European ethnic groups. About Italian unification see [Rene A. C., Italy from Napoleon to Mussolini, New York: Columbia University Press, 1962; Smith D. M., Mazzini, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994; Lucy R., The Italian Risorgimento. State, Society and National Unification, London−New York: Routledge, 1994; Lucy R., Cavour and Garibaldi, 1860: A Study in Political Conflict, Cambridge, 1985; Beales D., The Risorgimento and the Unification of Italy, London, 1981; Hearder H., Italy in the Age of the Risorgimento, 1790−1870, London, 1983; Coppa F., The Origins of the Italian Wars of Independence, London, 1992; Delzell C. F. (ed.), The Unification of Italy, 1859−1861. Cavour, Mazzini or Garibaldi?, New York, 1965]. About German unification see [Michael J., The Unification of Germany, London−New York, Routledge, 1996; Rodes J. E., The Quest for Unity. Modern Germany 1848−1970, New York−Chicago: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1971; Pflanze O., Bismark and the Development of Germany. Volume I: The Period of Unification, 1815−1871, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1962; Pflanze O. (ed.), The Unification of Germany, 1848−1871, European Problem Studies, New York−Chicago: University of Minnesota, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969; Medlicott E., Bismarck and Modern Germany, Conn.: Mystic, 1965; Darmstaedter F., Bismarck and the Creation of the Second German Reich, London, 1948].

[xx] Prof. Joseph Marko’s lecture: “State Formation and Nation-Building in Europe, Summer Academy 2000: “Regions and Minorities in a Greater Europe, European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano, September 2000, Bressanone/Brixen, Italy.

[xxi] The best example of this practice in the region is the case of Kosovo-Metochia’s Albanians who enjoyed the highest level of national-political-cultural autonomy in ex-Yugoslavia, even de facto national-territorial independence, but all the time have been fighting for separation of Kosovo-Metochia from Serbia and inclusion of this province into a Greater Albania. About Albanian renaissance in political thought see [Ypi L. L., “The Albanian Renaissance in Political Thought: Between the Enlightenment and Romanticism”, East European Politics & Societies, Vol. 21, № 4, 2007, pp. 661−680].

[xxii] However, originally, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia proclaimed in 1943 only five Yugoslav nationalities with their republics: the Muslims have been added after the Second World War.

[xxiii] Each of these ten “Nationalities of Yugoslavia”, except Gypsies (Roma) and Ruthenians, had (has) its national state outside Yugoslavia.

[xxiv] “Yugoslavism” was only unifying ideology, but it never was and real identity” [Pavlowitch S. K., “Yugoslavia: the failure of a success”, Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans, Vol. 1, № 2, 1999, pp. 163–170].

[xxv] Poulton H., The Balkans: Minorities and States in Conflict, London: Minority Rights Publications, 1994, p. 5.

[xxvi] According to the 3rd Article of the “Vidovdan” Constitution of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from June 28th, 1921, the official language in the state was Serbo-Croat-Slovenian one [Димић Љ., Културна политика Краљевине Југославије 1918−1941, Трећи део: Политика и стваралаштво, Београд: Стубови културе, 1997, p. 382]. About the process of creation of the first Yugoslav state see [Sotirović B. V., Creation of the First Yugoslavia: How the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was established in 918, Saarbrucken: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2012].

[xxvii] Smith A., “The ethnic sources of nationalism”, Survival, Vol. 35, № 1, pp. 5−26.

[xxviii] For instance, Kosovo-Metohija is always seen by the Serbs as a part of a national mythology as a cradle of Serbian nation and political and cultural center of national state. See: Шмаус А., “Из проблематике историјског развоја косовске традиције”, Зборник Филозофског факултета у Београду, VIII-2, 1969, pp. 617–624. About Kosovo-Metohija in Serbian history see: Самарџић Р. (and others), Косово и Метохија у српској историји, Београд: Српска књижевна задруга, 1989.

[xxix] Smith A., “Nations and their pasts”, Nations and Nationalism, Vol. 2, № 3, November 1996, p. 359. With the break up of the Socialist Yugoslavia the Communist ideology, as a “cement” of a common existence of different nations, nationalities and ethnic minorities, was replaces by a historical memories, which played the role of the “archive of animosity”.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS