Views: 884

There are many talks about nationalism among the peoples from the former Yugoslavia during the last three decades what is quite understandable taking into consideration the post-Cold War conflicts and atrocities, as a continuation of WWII crimes based on certain political ideologies,[i] committed on the territory of ex-Yugoslavia.

Historia est magistra vitae

I want to argue that there is a direct link between contemporary nationalism(s) among the Yugoslavs and their national ideologies, which are developed in the previous decades and even centuries. What happened with the Yugoslavs from 1991 to 1999 and probably to be repeated in the 21st century once again, it cannot be explained and understood without proper knowledge of their national histories, interethnic relations, and above all without familiarity with historical developments of the Yugoslav, South Slavic, and Balkan nationalism(s) in the European context.[ii] Whoever wants fairly to resolve any contemporary problem in the Balkans has to have a profound knowledge of Balkan history. If somewhere the motto Historia est magistra vitae is useful for the settlement of the current problems, it is exactly the Balkans and especially ex-Yugoslavia. Therefore, it should be known that among the Balkan peoples, national history is understood as a long-standing continuation of efforts that are leading to transform the ethnolinguistic group from the status of ethnos into the status (or level) of the nation.[iii] It practically means that the final historical and natural “task” of every Balkan ethnic group is to live in the united nation-state.[iv] This “national sacral task” is to be realized by any means.

Clearly, territory and a common will to live together are the crucial elements in the definition of nation in the case of the Yugoslav and the Balkan peoples (and many others as well).[v] There is no nation without definitely marked borders of the territory where the nation is living. The members of a nation have a consciousness of the exact borders of the territorial distribution of their ethnic compatriots.[vi] Consequently, ethnographic borders should be transformed into nation-state borders; i.e. state’s borders should follow current ethnolinguistic dispersion of people, but as well as to the great extent and historical borders of the “national” state. No more – no less! Historical consequence, however, was (and is) that there was more blood than available land for satisfaction of every single national claim in the ex-Yugoslavia and the Balkans.[vii]

Migrations and the national rights

The Yugoslav nationalism(s) is composed of seven main elements: I) territory; II) state; III) language and alphabet; IV) history and collective memory; V) religion; VI) people; and VII) tradition and customs. The essence is that according to the national(istic) perceptions, a single culturally and linguistically homogenous ethnic group (people) had been living in the past on its own ethnographic space. However, due to historical circumstances like foreign occupations, wars, famines, etc. (for example, the Ottoman occupation, German conquest, Hungarian and Italian rule, permanent shortage of food in Montenegro and Herzegovina), one bigger or smaller part of the national community left its own genuine (national) soil and went to diaspora settling itself on the territories of the “others” (for instance, Serbs from Kosovo-Metohija, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbia proper to South Hungary, Slavonia, Srem, Croatia, and Dalmatia in 1690 and 1737).[viii]

However, in the meantime, the “abandoned” national soil was resettled with “newcomers” of different ethnolinguistic background in comparison with the “genuine owners” of this soil, for instance, Albanian migrants to Kosovo’s plain from North Albania’s mountains after the First Serbian Great Migration from that region in 1690. Nevertheless, according to the “historical rights”, the nation of the “genuine ownership” of the soil in question has a legitimate right to resettle itself once again to the disputed territory and, even more, to include this territory, which historically belongs to the “genuine ownership-nation”, into a united national state like, for instance, the territory of “Srpska Krajina” in Croatia, Kosovo, “Turkish Croatia”[ix] in Bosnia, West Macedonia, etc.).

Furthermore, according to the “ethnic rights” of a nation, certain territories where the nation is in majority and living there for a long period (regardless that these territories are not belonging to the nation according to the “historic rights”) had to be included into the nation-state, too. For instance, Serbs claim the territory of “Srpska Krajina” in the Republic of Croatia according to Serbian “ethnic rights” (and morality because of the genocide, i.e. ethnocide, that was committed on Serbs in this region by the Nazi Ustashi Government of Croatia during WWII), but at the same time, the Serbian demand upon Kosovo-Metochia is mainly based on their “historic rights” regarding this particular region. A totally complicated situation emerged when the Croats claim the territory of “Srpska Krajina” according to the Croatian “historic rights”, and the Albanians are demanding Kosovo-Metochia according to their “ethnic rights”.[x] Unfortunately, the way out from such stalemate situation of overlapping of different rights of several nations over the same territories is found in forced deportations, expulsions, ethnic cleansing and genocide/ethnocide committed at the moment by politically and military stronger ethnolinguistic community over the weaker one(s) with help by some of the international Great Powers (like the present-day ethnic cleansing of the Serbs and other non-Albanians by local Albanians in South Serbia’s autonomous province of Kosovo-Metochia with direct support by the US, NATO, and EU administrations).[xi]

The “ethnic” society is usually preferred instead of “civil” society among the Yugoslavs.[xii] Probably, the main reason for this preference is the fact that a person is usually identifying himself with a nation, i.e. with national belonging; but a nation can be “realized” only in its own national state. I agree with the opinion that the strongest and the best loyalty is loyalty towards a nation-state. National culture can be as well as better preserved and further developed within the nation-state borders. Surely, one of the crucial preconditions for freedom all over the globe (or at least in the Balkans) is a strengthening of the nation-states.[xiii] However, there are no real nation-states without clearly fixed national borders.

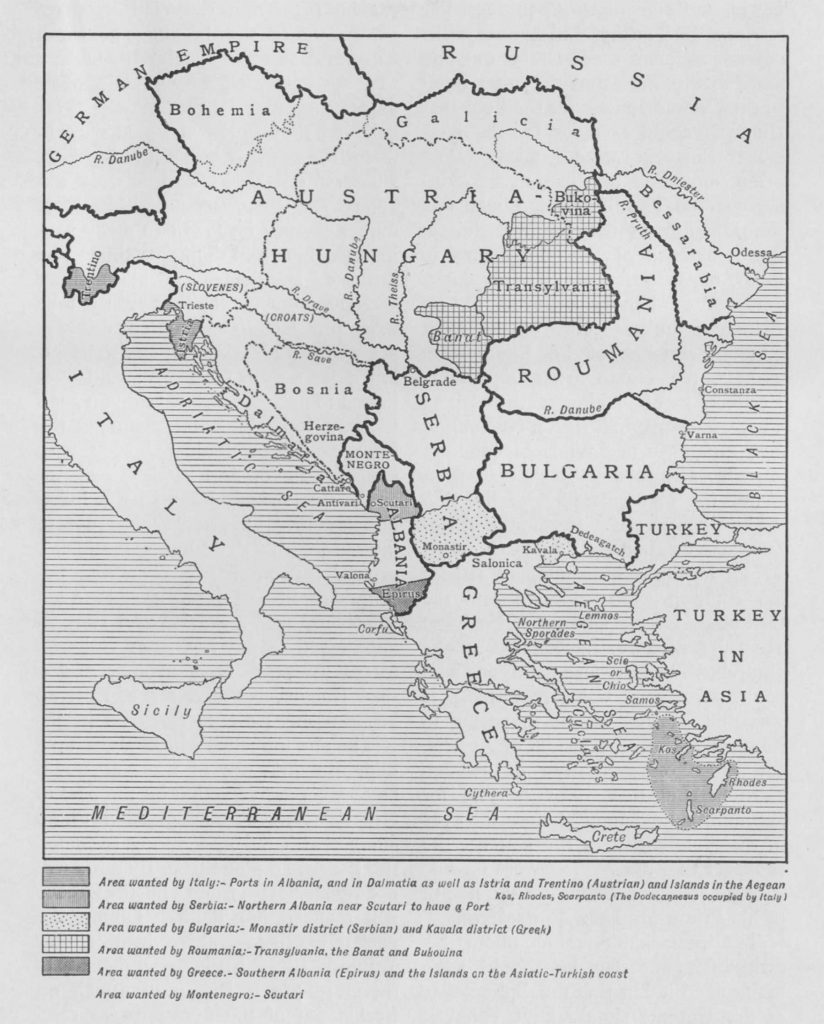

If one would compare the size of present-day independent states in the Balkans with their size from the previous centuries when they first became autonomous and later independent (Montenegro in 1516/1878; Serbia in 1829/1878; Greece in 1829/1830; Bulgaria in 1878/1908; Romania in 1859/1878) she/he will notice that these states in the time of achieving autonomous status and independence included no more than a half of the territory ruled by them nowadays. All of them obtained their autonomy and independence by the secession from the declining Ottoman Empire (the “Sick Man on the Bosporus”) and later enlarged their national territories by the irredentist policy of conquering still “non-liberated” national soil. The purpose of such a policy of irredentism was to overlap nation-state borders with the ethnographic borders of their national ethnic dispersion. This process is not finished until today. This irredentist attitude led all Balkan countries to the serious ethnic conflicts during the last two centuries because of the mixed population on many territories (for instance, “Srpska Krajina” in Croatia, Kosovo-Metochia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Vojvodina, West Thrace, Epirus, etc.) and the lack of clear national awareness in these lands (for instance, the Slavic population in the 19th-century Macedonia).

According to Robert Hislope, there are four factors of ethnic conflicts, either among the Yugoslavs or elsewhere: 1) the primary source of contention; 2) cleavage lines; 3) the role of culture; and 4) the role of elite.[xiv]

The results of ethnic conflicts between the Yugoslavs are:

- Two hundred years of animosities and warfare.

- Assimilation of the minorities.

- Repression of the minorities.

- Ethnic cleansing.

- Promotion of historical revisionism.

Greater nation-states

The national dreams of the creation of united, enlarged, and greater national states, however, are only partially realized by the Yugoslavs and other South-East European peoples in several historical occasions (as results of either struggle against the foreign rule or inter-ethnic conflicts). It can be seen from the list below:

List № 1. Realization of the greater (partly or almost united) national-states in South-East Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries:

A Greater Bulgaria in 1878 (“San Stefano Bulgaria”)

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Bulgaria proper (from Danube River to the Balkan Range and from Timok River to the Black Sea), East Rumelia (from the Balkan Range to Adrianople/Edirne including upper and middle stream of Maritza River with Philippopel/Plovdiv and Burgas on the littoral of the Black Sea), the whole portion of Vardar Macedonia (present-day independent state of North Macedonia including Bitola and Ohrid), part of Aegean Macedonia including Kastoria, Kavala, and Seres in present-day Greece to Thessaloniki and Chalkidiki Peninsula, south-east part of present-day Albania including Koritza, parts of present-day South-East Serbia including Vranje, Pirot, Caribrod, and Bosiljgrad, South Dobrodgea (Dobrudscha) including Mangalia, and part of present-day European Turkey up to Midia on the Black Sea littoral.

A Greater Romania in 1918−1940

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Romania proper (Wallachia and Moldavia-from the Danube, the Carpathian Mountains, Transylvanian Alps to the River of Prut), the whole portion of Dobrodgea (including South Dobrodgea with Silistria), Bessarabia, Bucovina, Transylvania, Eastern Banat, Crisana, and Maramures.

A Greater Serbia in 1913−1915

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Serbia proper (from the River of Danube to the lower stream of the River of South Morava and the River of Ibar and from the River of Drina to the River of Timok), South-East Serbia (with the cities of Vranje, Nish, Leskovac, and Pirot and the region of Toplica), North Sanjak (with the cities of Novi Pazar, Sjenica, Prijepolje, Nova Varosh, and Priboj), East Kosovo, and Vardar Macedonia (present-day the Republic of North Macedonia).

A Greater Croatia in 1943−1945 (an “Independent State of Croatia”)

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Croatia proper (from the River of Drava to Senj and from the River of Sutla to the River of Korana including the cities of Zagreb, Karlovac, Varazdin, Sisak, and Petrinja), Slavonia (from the River of Drava to the River of Sava), the whole portion of Srem (between the Rivers of Danube and Sava), whole Dalmatia, the region of Dubrovnik, the Adriatic Islands, the whole portion of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and whole Istrian Peninsula.

A Greater Slovenia since 1945

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Slovenia proper (Carniola or Krain or Kranjska), South Styria or Steiermark or Shtajerska, South Karinthia or Kärnten or Korushka, Slovenian littoral with the cities of Koper, Portoroz, Izola, and Piran, Prekomurije with the city of Murska Sobota, and West Medjumurje.

A Greater Albania in 1941−1944

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Albania proper (from the city of Scodra or Skutari or Skadar and the Prokletije Range to the Devoll and the upper stream of the River of Vjosë, and from the River of Drim and Ohrid Lake to the Adriatic littoral), Kosovo with Metochia including Prishtina, Pec/Peja, Gusinje, and Gnjilane (but without the town of Mitrovica), East Montenegro including Ulcinj (but without Bar) and North-West Macedonia including Struga, Kichevo, Debar, Tetovo, Gostivar (but without Ohrid).

A Greater Hungary in 1938−1944

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Hungary proper (present-day Hungary, i.e. Hungary around the Alföld Plain), South Slovakia, Ruthenia, North Transylvania, Prekomurje, Medjumurje, South Baranja, and Bachka.

A Greater Montenegro 1913−1916

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Montenegro proper or “Ancient Montenegro” (from Mt. Lovcen to the River of Zeta and from Pusti lisac to Sutorman including Cetinje, Rijeka Crnojevica, Virpazar and Kchevo), Rudine, Vasojevici, Shavnik, Podgorica region, the littoral from Skadar Lake to Bar, Ulcinj and the River of Bojana, Nikshic, Durmitor, Kolashin, Sinjajevina, the land around the River of Piva, South Sanjak with Pljevlja, Shahovici, Bijelo Polje, Mojkovac, Berane, Rozaje, Gusinje, Plav and the River of Ceotina, West Kosovo, which is called Metochia including Djakovica, Pec, and Istok and the area around the central portion of Skadar Lake.

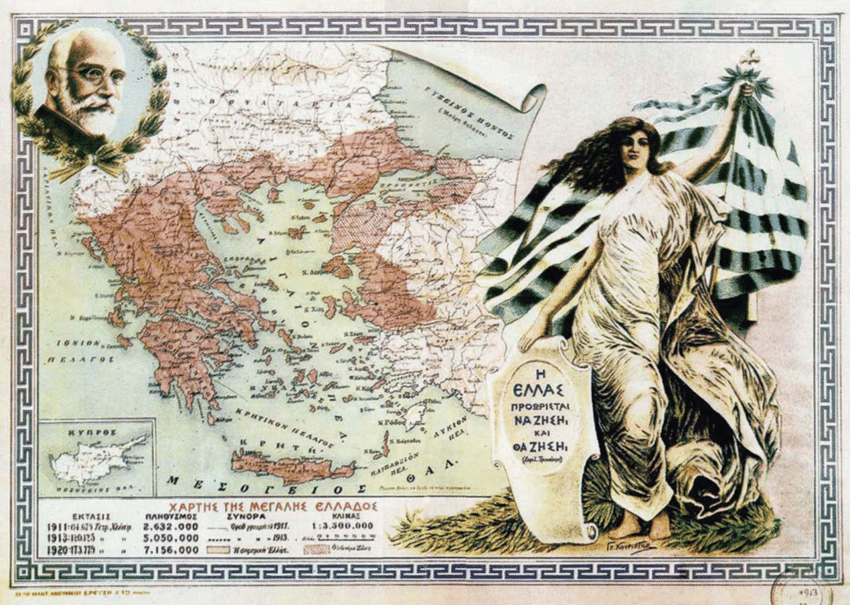

A Greater Greece 1919−1922

Territories included into the national-state borders:

Greece proper (Morea, Livadia, and Attica), the Ionian Islands, western part of the Aegean Islands (the Cyclades and the Sporades), Thessaly with Larissa and Gulf of Volos, South Epirus with Ioannina, Aegean Macedonia with Thessaloniki, the Chalkidiki Peninsula and Kavala, the Island of Crete, the rest of the Aegean Islands, West Thrace with the littoral and Smyrna region in Asia Minor.

Nevertheless, the national-territorial aspirations would be totally realized only when the entire ethnic and historical lands are included into the borders of nation-states. Therefore, a final national aim is to achieve a total national unification by the creation of a “united” nation-state. The list below shows the “ideal solutions of national questions” at the Balkans from a territorial point of view:

List № 2. The territorial realization of totally united nation-states in South-East Europe in the future:[xv]

United Bulgaria

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Bulgaria, Vardar Macedonia (present-day independent North Macedonia), whole Dobrodgea, Aegean Macedonia with Thessaloniki, Kavala and the Chalkidiki Peninsula, a south-east portion of present-day Albania (around the Lakes of Ohrid and Prespa including the city of Koritza), the eastern part of present-day Serbia (from the River of Grand Morava to the Bulgarian border), and the European part of present-day Turkey (East Thrace).

United Romania

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Romania, historical Bessarabia (present-day independent Moldova and the Black Sea littoral from the River of the Dniester to the River of Prut), whole Banat, Crisana (eastern part of present-day Hungary from the River of Tisa to Transylvania), Maramures, whole Bucovina, and whole Dobrodgea.

United Serbia

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Serbia and Montenegro (including Serbia’s autonomous provinces of Kosovo-Metochia and Vojvodina), the territory of present-day North Macedonia (or Vardar Serbia), whole Bosnia-Herzegovina, Dubrovnik, South and Central Dalmatia, the territory of former “Republika Srpska Krajina” (1991−1995), and North Albania with Durres.

United Croatia

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Croatia, whole Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro (or “Red Croatia”), Slovenia (or “Alpine Croatia”), East Srem, and Bachka.

United Slovenia

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Slovenia, the city and region of Trieste, part of Italy to the west from the River of Socha, North Carniola with Villach (or in Slovenian Beljak) and Klagenfurt (or in Slovenian Celovec), and part of Austrian Styria.

United Albania

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Albania, whole Kosovo-Metochia, whole West Macedonia including Ohrid, Prespa, Veles, Kumanovo, and Skopje (up to the River of Vardar), East Montenegro including Podgorica, Bar, and Ulcinj, South-East Serbia including Medvedja, Bujanovac, Vranje, and Preshevo, and South Epirus with Ioannina (today North-West Greece).

United Hungary

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Hungary, whole Transylvania, South Slovakia, Medjumurje, Prekomurje, South Baranja, Srem, whole Banat, and Bachka.

United Montenegro

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Montenegro, Metochia (Western Kosovo), North Sanjak, South Dalmatia with Dubrovnik (from Kotor to the River of Neretva), whole Herzegovina, and part of North Albania with Scutari.

United Greece

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day Greece, North Epirus (or South Albania), Smyrna region in Asia Minor, part of Vardar Macedonia, whole Cyprus, and European portion of Turkey with Constantinople/Istanbul.

United Bosnia-Herzegovina

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

The territory of present-day (“Dayton”) Bosnia-Herzegovina (“Republika Srpska” and “Federation of B-H”), whole Sanjak, part of West Serbia (districts of Jadar and Radjevina), and part of Dalmatia.

United Macedonia

Territories which should be included to united nation-state:

Territories of present-day North Macedonia (Vardar Macedonia), Aegean Macedonia (the Greek Macedonia) and Pirin Macedonia (the Bulgarian Macedonia) – from Mt. Olympus to Mt. Shara and from Mt. Pindus to Mt. Rhodopes.

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

Endnotes:

[i] That the war of dissolution and destruction of ex-Yugoslavia in 1991−1999 was understood by many Yugoslavs as a direct continuation of, or retaliation for, the mass atrocities committed during WWII, especially against the Serbs on the territory of the Independent State of Croatia, confirm many interviews with the local inhabitants (see, for instance [BBC documentary movie: Death of Yugoslavia; Guskova J., Istorija jugoslovenske krize, I, Beograd: IGA “M”, 2003, 311]). Regarding a Nazi Croat-run ethnocide committed on the local Serb civilians within the territory of the Independent State of Croatia, which included Bosnia-Herzegovina as well as West Serbia’s province of Srem, from 1941 to 1945 see in [Bulajić M., The Role of the Vatican in the Break-up of the Yugoslav State, Belgrade: The Ministry of Information of the Republic of Serbia, 1993; Ривели М. А., Надбискуп геноцида. Монсињор Степинац, Ватикан и усташка диктатура у Хрватској, 1941−1945, Никшић: Јасен, 1999; НД Хрватска. Држава геноцида, Двери српске. Часопис за националну културу и друштвена питања, год. XIII, бр. 47−50, Београд, 2011; Novak V., Magnum Crimen: Pola vijeka klerikalizma u Hrvatskoj, Zagreb, 1948 (reprint Beograd: BIGZ, 1986); Сотировић Б. В., Огледи из Југославологије, Виљнус: Штампарија Литванског едуколошког универзитета „Едукологија“, 2013, 201−207].

The Independent State of Croatia had totally free and independent policy regarding its own internal affairs what finally resulted in the killings on the most brutal way around at least 700.000 of the Serbs. Regarding the Croat claims on the question of population losses during WWII on the territory of ex-Yugoslavia, see [Žerjavić V., Population Losses in Yugoslavia 1941−1945, Zagreb: Hrvatski institut za povijest, 1997]. The German experts and military institutions were estimating that around 750,000 men have been killed by the Croats and Muslims on the territory of the Independent State of Croatia, while the Government of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina found the number of around 700,000 killed (mainly Serbs) only in the death-camp of Jasenovac on the River of Sava [Екмечић М., Дуго кретање између клања и орања. Историја Срба у новом веку (1492−1992), Београд: Evro−Giunti, 2010, 451].

[ii] Regarding genesis and development of European nationalism(s) see in [Wilson T. M., Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontiers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998; Silvert K. H., Exceptant Peoples: Nationalism and Development, New York: Random House, 1963; Nationalism, London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, Frank Cass, 1963; Diamond L. J., Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Democracy, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994; Hobsbawm E. J., Nations and Nationalism since 1780. Programme, Myth, Reality, Cambridge: Canto, Cambridge University Press, 1992]. Regarding genesis and development of Serbian and Croatian nationalism(s) in the 19th century see in Bukowski J., “Yugoslavism and the Croatian National Party in 1867”, Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism, Vol. 3, № 1, 1975, 70−88; Đorđević M., Srpska nacija u građanskom društvu, Beograd: Narodna knjiga, 1979; MacKenzie D., “Serbian Nationalist and Military Organizations, 1844−1914”, East European Quarterly, 16, 1982, 323−344; MacKenzie D., The Serbs and Russian Pan-Slavism 1875−1878, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967; Meriage L. P., “The First Serbian Uprising (1804−1813): National Revival or a Search for Regional Security”, Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism, Vol 4, № 1, 1977, 87−205; Mirković M., Janjić D. (eds.), Postanak i razvoj srpske nacije, Beograd: Narodna knjiga, 1979; Perović R., “Oko Načertanija iz 1844 godine”, Istorijski glasnik, № 1, 1963, 71−94; Gale S., “The Absence of Nationalism in Serbian Politics Before 1844”, Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism, Vol. 4, № 2, 1976, 77−90; Boban Lj., “Misija Jancikovića u inozemstvo”, Časopis za suvremenu povijest, XII, № 1, 1980, 27−74; Bogdanov V., Historija političkih stranaka u Hrvatskoj od prvih stranačkih grupiranja do 1918, Zagreb: Novinarsko izdavačko poduzeće, 1958; Ciliga V., Slom politike Narodne stranke (1865−1880), Zagreb: Matica Hrvatska, 1970; Despalatović E. M., Ljudevit Gaj and the Illyrian Movement, New York−London: Boulder, East European Monographs, 1975; Dizdar Z., “Ljubljanski ‘Jugoslavenski kongres’ 1870 u najnovijoj literaturi”, Historijski zbornik, 27−28, 1974−75, 331−341; Gross M., “Einfluss der sozialen Struktur auf den Charakter der Nationalbewegung in den Kroatischen Ländern im 19. Jahrhundert”, Schieder Th. (ed.), Sozialstruktur und Organisation Europäischer Nationalbewegungen, Münich−Oldenbourg, 1971, 67−92; Gross M., Povijest pravaške ideologije, Zagreb: Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Institut za Hrvatsku povjest, 1973; Hrvatski narodni preporod u Dalmaciji i Istri, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1969; Jelavich Ch., “The Croatian Problem in the Habsburg Empire in the 19th Century”, Austrian History Yearbook, 3, 1967, 83−115; Pavličević D., Narodni pokret 1883 u Hrvatskoj, Zagreb: Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Institut za hrvatsku povjest, 1980; Petrović R., Nacionalno pitanje u Dalmaciji u XIX stoljeću: Narodna stranka i nacionalno pitanje 1860−1880, Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1968; Pribić B., “Srpsko pitanje pred Hrvatskim saborom godine 1861”, Časopis za suvremenu povjest, Vol. 12, № 1, 1980, 75−96; Stančić N., Hrvatska nacionalna ideologija preporodnog pokreta u Dalmacuji: Mihovil Pavlinović i njegov krug do 1869, Zagreb: Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Centar za povjesne znanosti, Odjel za hrvatsku povjest, 1980; Vuchinich W., “Croatian Illyrism: Its Background and Genesis”, Winters S. B., Held J. (eds.), Intelectual and Social Developments in the Habsbourg Empire from Maria Theresa to World War I: Essays Dedicated to Robert Kann, Boulder−New York: East European Monographs, 1975, 55–113.

[iii] Regarding the politics of history education in the Balkan societies at the beginning of the 21st century, see in [Koulouri Ch. (ed.), Clio in the Balkans. The Politics of History Education, Center for Democracy and Reconciliation in Southeast Europe, Thessaloniki: Petros Th. Ballidis & Co., 2002].

[iv] Anthony Smith claims that this national historical “task” is accepted by every nation. See [Smith A., The Ethnic Origins of Nations, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1986].

[v] Dumont L., Religion, Politics and History in India, Paris: Mouton, 1970, 70.

[vi] Mauss M., “La nation”, L’ Annèe Sociologique, 3e sèrie, 16–17. See [Smith A., National Identity, Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1991; Smith A., The Ethnic Origins of Nations, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986; Weber E., Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1976; Edwards J., Language, Society, and Identity, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1985; Connor W., “A Nation Is a Nation, Is a State, Is an Ethnic Group, Is a…”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 1, №. 4, 1978, 377–400.

[vii] See [Köksal Y., “Rethinking Nationalism: State Projects and Community Networks in 19th-Century Ottoman Empire”, American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 51, № 10, 2008, 1498−1515].

[viii] See [Cvijić J., Metanastazička kretanja, njihovi uzroci i posledice, Beograd: Srpska kraljevska akademija, 1922; Чакић С., Велика сеоба Срба 1689/90 и патријарх Арсеније III Црнојевић, Нови Сад: Добра вест, 1990]. About immigration and emigration from a historical perspective, see in more details in [Isaacs K. A. (ed.), Immigration and Emigration in Historical Perspective, Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2007].

[ix] From the time when the Ottomans transformed Bosnia-Herzegovina into Bosnian pashalik in 1580, “Croatia Turcica” became the term to mark the last conquered part of historic Croatia by the Ottomans that was, according to the Croat historiography, the land between the Rivers of Vrbas and Una. The rest of the historic Croatia, known as Reliquiae reliquiarum became part of the Habsburg Monarchy on January 1st, 1527. The Croatian “Reconquista” started in 1699, by Karlowitz (Sremski Karlovci) Peace Treaty, followed by the Treaty of Passarowitz (Požarevac) in 1718 and by the Treaty of Svishtov in 1791. Subsequently, present-day borders of the Republic of Croatia are mainly products of these treaties. Finally, in 1954, when the Trieste crisis became resolved between Italy and Yugoslavia the main part of the Istrian Peninsula (which never was part of the Croatian state before) became part of the Socialist Republic of Croatia. Borders between Hungary and Croatia on the River of Drava and Croatia and Slovenia nearby Zagreb are ones of the oldest in Europe.

[x] A similar situation was with the “Macedonian Question” from 1870 to 1912 as disputed land between Serbian, Bulgarian, Albanian, and Greek nationalistic and territorial claims. See [Sotirović B. V., “Macedonia between Greek, Bulgarian, Albanian and Serbian national aspirations”, Serbian Studies: Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies, Vol. 23, № 1, 2009 (2011), 12−40].

[xi] See the Canadian documentary movie Kosovo, Can You Imagine? directed by Boris Malagurski in 2009 on YouTube.

[xii] While the French Revolution of 1789–1794 declared the “Right of Man”, the German philosophy of Romanticist nationalism declared the “Right of Nation”. The Yugoslavs like many others followed the latter option.

[xiii] Smith A., Theories of Nationalism, London: Duckworth, 1983, 21.

[xiv] Hislope R., “Can evolutionary theory explain nationalist violence?”, Nations and Nationalism, ASEN, Vol. 4, 1998, 474−477.

[xv] The most extreme territorial claims are not represented in the list.

Originally published at OrientalReview.org website.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]