Views: 3263

Editor’s note: Originally posted on 2016-01-11

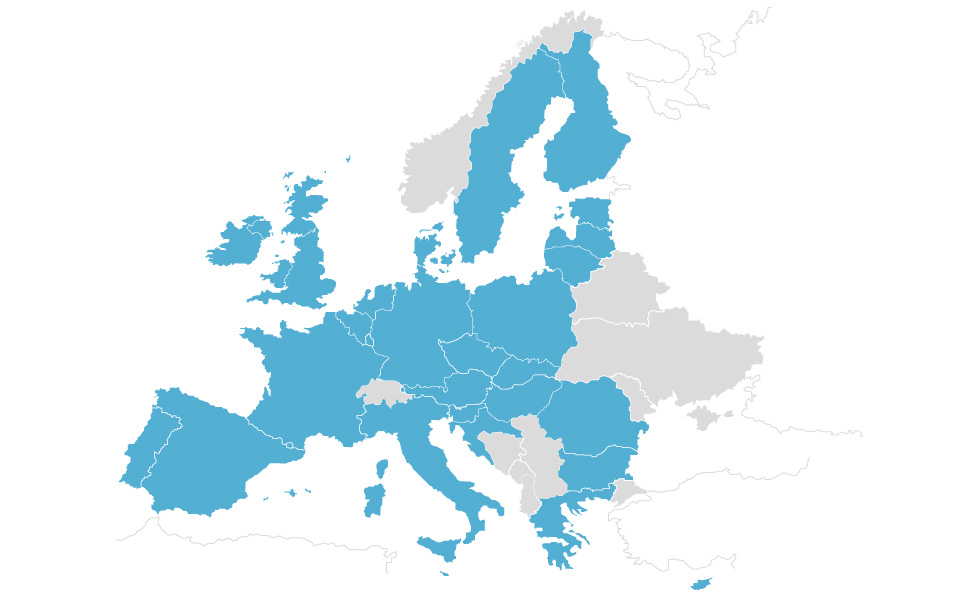

Serbia entered on December 14th, 2015 a final stage of negotiations with Brussels on the EU’s membership. It is known, however, that the EU gave an informal ultimatum to Serbia to recognize Kosovo’s independence for the exchange of becoming a full Member State of the EU. The western (the USA/EU) client Serbia’s Government is currently under the direct pressure from Brussels to recognize an independence of the narco-mafia Kosovo’s quasi state or to give up an idea to join the EU. It is only a question when a western colony of Serbia has to finally declare its official recognition of Kosovo’s independence. The President of Serbian Academy of Science and Arts, like all other western bots in Serbia, already publicaly announced his official position in regard to this question: Serbia’s Government has to finally inform the Serbian nation that Kosovo-Metochia is not any more an integral part of Serbia and therefore the recognition of Kosovo’s independence by Belgrade is only way towards a prosperous future of the country that is within the EU (and the NATO’s pact as well).

Serbia entered on December 14th, 2015 a final stage of negotiations with Brussels on the EU’s membership. It is known, however, that the EU gave an informal ultimatum to Serbia to recognize Kosovo’s independence for the exchange of becoming a full Member State of the EU. The western (the USA/EU) client Serbia’s Government is currently under the direct pressure from Brussels to recognize an independence of the narco-mafia Kosovo’s quasi state or to give up an idea to join the EU. It is only a question when a western colony of Serbia has to finally declare its official recognition of Kosovo’s independence. The President of Serbian Academy of Science and Arts, like all other western bots in Serbia, already publicaly announced his official position in regard to this question: Serbia’s Government has to finally inform the Serbian nation that Kosovo-Metochia is not any more an integral part of Serbia and therefore the recognition of Kosovo’s independence by Belgrade is only way towards a prosperous future of the country that is within the EU (and the NATO’s pact as well).

In the following paragraphs we would like to present the most important features of the “Kosovo Question” for the better understanding of the present political situation in which the Serb nation is questioned by the western “democracies” upon both its own national identity and national pride.

Prelude

The south-eastern province of the Republic of Serbia – under the administrative title of Kosovo-Metochia (in the English only Kosovo), was at the very end of the 20th century in the center of international relations and global politics too due to the NATO’s 78 days of the “humanitarian” military intervention against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (The FRY which was composed by Serbia and Montenegro)[1] in 1999 (March 24th–June 10th). As it was not approved and verified by the General Assembly or the Security Council of the United Nations, the US-led operation “Merciful Angel” opened among the academicians a fundamental question of the purpose and nature of the “humanitarian” interventions in the world like it was previously in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1995, Rwanda in 1994 or Somalia in 1991−1995.[2] More precisely, it provoked dilemmas of the misusing ethical, legal and political aspects of armed “humanitarian” interventions as the responsibility to protect for the very reason that it became finally obvious in 2008 that the NATO’s “humanitarian” military intervention in 1999 was primarily aimed to lay the foundation for Kosovo’s independence and its separation from Serbia with transformation of the province into the US−EU’s political-economic colony.[3]

The Balkan Peninsula

Kosovo as contested land between the Serbs and the Albanians

The province of Kosovo-Metochia (Kosova in the Albanian), as historically contested land between the Serbs and the Albanians, did not, does not and will not have an equal significance for those two nations. For the Albanians, Kosovo was all the time just a provincial land populated by them without any cultural or historical importance except for the single historical event that the first Albanian nationalistic political league was proclaimed in the town of Prizren in Metochia (the western part of Kosovo) in 1878 and existed only till 1881. However, both Kosovo as a province and the town of Prizren were chosen to host the First (pan-Albanian) Prizren League[4] only for the very propaganda reason – to emphasize allegedly predominantly the “Albanian” character of both Kosovo and Prizren regardless to the very fact that at that time the Serbs were a majority of population either in Kosovo or in Prizren.[5] Kosovo was never part of Albania and the Albanians from Albania had no important cultural, political or economic links with Kosovo’s Albanians regardless the fact that the overwhelming majority of Kosovo Albanians originally came from the North Albania after the First Great Serbian Migration from Kosovo in 1690.[6]

However, quite contrary to the Albanian case, Kosovo-Metochia is the focal point of the Serbian nationhood, statehood, traditions, customs, history, culture, church and above all of the ethno-national identity. It was exactly Kosovo-Metochia to be the central administrative-cultural part of the medieval Serbia with the capital in Prizren. The administrative center of the medieval and later Ottoman-time Serbian Orthodox Church was also in Kosovo-Metochia in the town of Peć (Ipek in the Turkish; Pejë in the Albanian). Before the Muslim Kosovo’s Albanians started to demolish the Serbian Christian Orthodox churches and monasteries after June 1999, there were around 1.500 Serbian Christian shrines in this province.[7] Kosovo-Metochia is even today called by the Serbs as the “Serbian Holy Land” while the town of Prizren is known for the Serbs as the “Serbian Jerusalem” and the “Imperial town” (Tsarigrad) in which there was an imperial court of the Emperor Stefan Dushan of Serbia (1346−1355). The Serbs, differently to the Albanians, have a plenty of national folk songs and legends about Kosovo-Metochia, especially in regard to the Kosovo Battle of 1389 in which they lost state independence to the Ottoman Turks.[8]

Nevertheless, there is nothing similar in the Albanian case with regard to Kosovo. For instance, there is no single Albanian church or monastery in this province from the medieval time or any important monument as the witness of the Albanian ethnic presence in the province before the time of the rule by the Ottoman Sultanate. Even the Muslim mosques from the Ottoman time (1455−1912) claimed by the Albanians to belong to the Albanian national heritage, were in fact built by the Ottoman authorities but not by the ethnic Albanians. The Albanian national folk songs are not mentioning the medieval Kosovo that is one of the crucial evidences that they simply have nothing in common with the pre-Ottoman Kosovo. All Kosovo’s place-names are of the Slavic (Serb) origin but not of the Albanian. The Albanians during the last 50 years are just renaming or adapting the original place-names according to their vocabulary what is making a wrong impression that the province is authentically the Albanian. We have not to forget the very fact that the word Kosovo is of the Slavic (the Serb) origin meaning a kind of eagle (kos) while the same word means simply nothing in the Albanian language. Finally, in the Serbian tradition Kosovo-Metochia was always a part of the “Old Serbia”[9] while in the Albanian tradition Kosovo was never called as any kind of Albania.

The province became contested between the Serbs and the Albanians when the later started to migrate from the North Albania to Kosovo-Metochia after 1690 with getting a privileged status as the Muslims by the Ottoman authorities. A Muslim Albanian terror against the Christian Serbs at the Ottoman time[10] resulted in the Abanization of the province to such extent that the ethnic structure of Kosovo-Metochia became drastically changed in the 20th century. A very high Muslim Albanian birthrate played an important role in the process of Kosovo’s Albanization too. Therefore, after the WWII the ethnic breakdown of the Albanians in the province was around 67 percent. The new and primarily anti-Serb Communist authorities of the Socialist Yugoslavia legally forbade to some 100.000 WWII Serb refugees from Kosovo-Metochia to return to their homes after the collapse of the Greater Albania in 1945 of which Kosovo was an integral part. A Croat-Slovenian Communist dictator of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito (1892−1980), granted to the province of Kosovo-Metochia a considerable political autonomous status in 1974 with a separate Government, Provincial Assembly, President, Academy of Science, security forces, independent university in Prishtina and even military defense system for the fundamental political reason to prepare Kosovo’s independence after the death of his Titoslavia.[11] Therefore, Kosovo-Metochia in the Socialist Yugoslavia was just formally part of Serbia as the province was from political-administrative point of view an independent as all Yugoslav republics. A fully Albanian-governed Kosovo from 1974 to 1989 resulted in both destruction of the Christian (Serb) cultural monuments[12] and continuation of mass expulsion of the ethnic Serbs and Montenegrins from the province to such extent that according to some estimations there were around 200.000 Serbs and Montenegrins expelled from the province after the WWII up to the abolition of political autonomy of the province (i.e. independence) by Serbia’s authority in 1989 with the legal and legitimate verification by the Provincial Assembly of Kosovo-Metochia and the reintegration of Kosovo-Metochia into Serbia.[13] At the same period of time, there were around 300.000 Albanians who illegally came to live in Kosovo-Metochia from Albania. Consequently, in 1991 there were only 10 percent of the Serbs and Montenegrins who left to live in Kosovo-Metochia out of a total number of the inhabitants of the province.[14]

A member of the KLA in 1998

Fighting Kosovo’s Albanian political terrorism and territorial secession

The revocation of Kosovo’s political autonomy in 1989 by Serbia’s central Government was aimed primarily to stop further ethnic Albanian terror against the Serbs and Montenegrins and to prevent secession of the province from Serbia that will result in the recreation of the WWII Greater Albania with the legalization of the policy of Albanian ethnic cleansing of all non-Albanian population what practically happened in Kosovo after June 1999 when the NATO’s troops occupied the province and brought to the power a classical terrorist political-military organization – the Kosovo’s Liberation Army (the KLA). Nevertheless, the Western mainstream media as well academia presented Serbia’s fighting Kosovo’s Albanian political terrorism and territorial secession after 1989 as Belgrade policy of discrimination against the Albanian population which became deprived of political and economic rights and opportunities.[15] The fact was that such “discrimination” was primarily a result of the Albanian policy of boycotting Serbia’s state institutions and even job places offered to them in order to present their living conditions in Kosovo as the governmental-sponsored minority rights oppression.

In the Western mainstream mass media and even in academic writings, Dr. Ibrahim Rugova, a political leader of Kosovo’s Albanians in the 1990s, was described as a person who led a non-violent resistance movement against Miloshevic’s policy of ethnic discrimination of Kosovo’s Albanians. I. Rugova was even called as a “Balkan Gandhi”.[16] In the 1990s there were established in Kosovo the Albanian parallel and illegal social, educational and political structures and institutions as a state within the state. The Albanians under the leadership of Rugova even three times proclaimed the independence of Kosovo. However, these proclamations of independence were at that time totally ignored by the West and the rest of the world. Therefore, Rugova-led Kosovo’s Albanian national-political movement failed to promote and advance the Kosovo’s Albanian struggle for secession from Serbia and independence of the province with a very possibility to incorporate it into a Greater Albania. I. Rugova himself, coming from the Muslim Albanian Kosovo’s clan that originally migrated to Kosovo from Albania, was active in political writings on the “Kosovo Question” as a way to present the Albanian viewpoint on the problem to the Western audience and therefore, as a former French student, he published his crucial political writing in the French language in 1994.[17]

One of the crucial questions in regard to the Kosovo problem in the 1990s is why the Western “democracies” did not recognize self-proclaimed Kosovo’s independence? The fact was that the “Kosovo Question” was absolutely ignored by the US-designed Dayton Accords of 1995 which were dealing only with the independence of Bosnia-Herzegovina.[18] A part to the answer is probably laying in the fact that Rugova-led Albanian secession movement was in essence illegal and even terroristic. It is known that Rugova himself was a sponsor of a terroristic party’s militia which was responsible for violent actions against Serbia’s authorities and non-Albanian ethnic groups in Kosovo.[19] For instance, in July 1988, from the graves of the village of Grace graveyard (between Prishtina and Vuchitrn) were excavated and taken to pieces the bodies of two Serbian babies of the Petrovic’s family.[20] Nevertheless, as a response to Rugova’s unsuccessful independence policy, it was established the notorious KLA which by 1997 openly advocated a full-scale of terror against everything what was Serbian in Kosovo.

The KLA had two main open political aims:

- To get an independence for Kosovo from Serbia with possibility to include the province into a Greater Albania.

- To ethnically clean the province from all non-Albanians especially from the Serbs and Montenegrins.

However, the hidden task of the KLA was to wage an Islamic Holy War (the Jihad) against the Christianity in Kosovo by committing the Islamic terror similarly to the case of the present-day Islamic State (the ISIS/ISIL) in the Middle East. Surely, the KLA was and is a part of the policy of radicalization of the Islam at the Balkans after 1991 following the pattern of the governmental (Islamic) Party of Democratic Action (the PDA) in Bosnia-Herzegovina.[21]

That the KLA was established as a terrorist organization is even confirmed by the Western scholars[22] and the US administration too. On the focal point of the Kosovo’s War in 1998−1999 we can read in the following sentence:

“Aware that it lacked popular support, and was weak compared to the Serbian authorities, the KLA deliberately provoked Serbian police and Interior Ministry attacks on Albanian civilians, with the aim of garnering international support, specifically military intervention”.[23]

Conclusions

It was true that the KLA realized very well that the more Albanian civilians were killed as a matter of the KLA’s “hit-and-run” guerrilla warfare strategy, the Western (the NATO’s) military intervention against the FRY was becoming a reality. In the other words, the KLA with his Commander-In-Chief Hashim Thaci were quite aware that any armed action against Serbia’s authorities and Serbian civilians would bring retaliation against the Kosovo Albanian civilians as the KLA was using them in fact as a “human shield”. That was in fact the price which the ethnic Albanians in Kosovo had to pay for their “independence” under the KLA’s governance after the war. That was the same strategy used by Croatia’s Government and Bosnian-Herzegovinian Muslim authorities in the process of divorce from Yugoslavia in the 1990s. However, as violence in Kosovo escalated in 1998 the EU’s authorities and the US’s Government began to support diplomatically an Albanian course – a policy which brought Serbia’s Government and the leadership of the KLA to the ceasefire and withdrawal of certain Serbian police detachments and the Yugoslav military troops from Kosovo followed by the deployment of the “international” (the Western) monitors (the Kosovo Verification Mission, the KVM) under the formal authority of the OSCE. However, it was in fact informal deployment of the NATO’s troops in Kosovo. The KVM was authorized by the UN’s Security Council Resolution 1199 on September 23rd, 1998. That was the beginning of a real territorial-administrative secession of Kosovo-Metochia from Serbia sponsored by the West for the only and very reason that Serbia did not want to join the NATO and to sell her economic infrastructure to the Western companies according to the pattern of “transition” of the Central and South-East European countries after the Cold War. The punishment came in the face of the Western-sponsored KLA.

Prof. Dr Vladislav B. Sotirovic

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirovic 2016

Join the debate on our Twitter Timeline!

__________________________

Endnotes:

[1] The FRY became renamed in February 2003 into the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro (the SCG) and finally the federation ended in June 2006 when both Serbia and Montenegro became independent states.

[2] On the “humanitarian” military interventions, see [J. L. Holzgrefe, R. O. Keohane (eds.), Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas, Cambridge−New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003; T. B. Seybolt, Humanitarian Military Intervention: The Conditions for Success and Failure, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2007; D. Fassin, M. Pandolfi, Contemporary States of Emergency: The Politics of Military and Humanitarian Interventions, New York: Zone Books, 2010; A. Hehir, The Responsibility to Protect: Rhetoric, Reality and the Future of Humanitarian Intervention, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; G. Th. Weiss, Humanitarian Intervention, Cambridge, UK−Malden, MA, USA: 2012; A. Hehir, Humanitarian Intervention: An Introduction, London−New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013; B. Simms, D. J. B. Trim (eds.), Humanitarian Intervention: A History, Cambridge−New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013; D. E. Scheid (ed.), The Ethics of Armed Humanitarian Intervention, Cambridge−New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014].

[3] H. Hofbauer, Eksperiment Kosovo: Povratak kolonijalizma, Beograd: Albatros Plus, 2009.

[4] On the First Prizren League, from the Albanian viewpoint, see [S. Pollo, S. Pulaha, (eds.), The Albanian League of Prizren, 1878−1881. Documents, Vol. I−II, Tirana, 1878].

[5] In 1878 the Serbs were about 60 percent of Kosovo population and 70 percent of Prizren inhabitants.

[6] On the First Great Serbian Migration from Kosovo in 1690, see [С. Чакић, Велика сеоба Срба 1689/90 и патријарх Арсеније III Црнојевић, Нови Сад: Добра вест, 1990].

[7] On the Serbian Christian heritage of Kosovo-Metochia, see [M. Vasiljvec, The Christian Heritage of Kosovo and Metohija: The Historical and Spiritual Heartland of the Serbian People, Sebastian Press, 2015].

[8] On the Kosovo Battle of 1389 in the Serbian popular tradition, see [Р. Пековић (уредник), Косовска битка: Мит, легенда и стварност, Београд: Литера, 1987; R. Mihaljčić, The Battle of Kosovo in History and in Popular Tradition, Belgrade: BIGZ, 1989; Р. Михаљчић, Јунаци косовске легенде, Београд: БИГЗ, 1989]. The President of Serbia – Slobodan Miloshevic, started his patriotic policy of unification of the Republic of Serbia and promulgation of the human rights for the Kosovo Serbs exactly on the 600 years anniversary of the Kosovo Battle that was celebrated on June 28th, 1989 in Gazimestan near Prishtina as the place of the battle in 1389. However, this event was commonly seen by the Western academia and policy-makers as an expression of the Serb nationalism [R. W. Mansbach, K. L. Taylor, Introduction to Global Politics, London−New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012, 429] and even as the Serb proclamation of the war to the rest of Yugoslavia.

[9] Р. Самарџић et al, Косово и Метохија у српској историји, Београд: Друштво за чување споменика и неговање традиција ослободилачких ратова Србије до 1918. године у Београду−Српска књижевна задруга, 1989, 5; Д. Т. Батаковић, Косово и Метохија: Историја и идеологија, Београд: Чигоја штампа, 2007, 17−29.

[10] See, for instance, a Memorandum by Kosovo and Macedonian Serbs to the international peace conference in The Hague in 1899 [Д. Т. Батаковић, Косово и Метохија у српско-арбанашким односима, Београд: Чигоја штампа, 2006, 118−123].

[11] From Josip Broz Tito, however, the Serbs in Croatia or Bosnia-Herzegovina did not receive any kind of political-territorial autonomy as Kosovo Albanians or Vojvodina Hungarians enjoyed in Serbia. Nevertheless, for the matter of comparison with Kosovo Albanians in Serbia, the Kurds in Turkey are not even recognized as a separate ethno-linguistic group.

[12] For instance, the Muslim Albanians tried to set arson on the Serbian Patriarchate of Pec’s church in the West Kosovo (Metochia) in 1981, but just accidentally only the dormitory was burnt.

[13] J. Palmowski (ed.), A Dictionary of Contemporary World History From 1900 to the Present Day, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 428.

[14] On the history of Kosovo from the Western perspective, see [N. Malcolm, Kosovo: A Short History, New York: New York University, 1999; T. Judah, Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2008].

[15] T. B. Seybolt, Humanitarian Military Intervention: The Conditions for Success and Failure, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2007, 79.

[16] Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869−1948) was an Indian national leader against the British colonial occupation of India. He became well-known as a leader who organized an Indian civil disobedience movement against the British colonial authorities which finally led to the independence of India. On his biography, see [J. Lelyveld, Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and his Struggle with India, New York: Knopf Borzoi Books, 2011].

[17] I. Rugova, La Question du Kosovo, Fayard, 1994. It has to be noticed that Rugova’s father and grandfather were shot to death by the Yugoslav Communist authorities at the very end of the WWII as the Nazi collaborators during the war.

[18] On the Dayton Accords, see [D. Chollet, The Road to the Dayton Accords: A Study of American Statecraft, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005].

[19] On this issue, see more in [В. Б. Сотировић, Огледи из Југославологије, Виљнус: приватно издање, 2013, 190−196].

[20] We can not forget as well that the KLA-led “March Pogrom” of Serbs in Kosovo (March 17−19th, 2004) was executed when I. Rugova was a “President” of Kosovo. The pogrom was in fact “…a systematic ethnic cleansing of the remaining Serbs…together with destruction of houses, other property, cultural monuments and Orthodox Christian religious sites” [D. Kojadinović (ed.), The March Pogrom, Belgrade: Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Serbia−Museum in Priština (displaced), 2004, 8].

[21] On the threat of radical Islam to the Balkans and Europe after 1991, see [Sh. Shay, Islamic Terror and the Balkans, Transaction Publishers, 2006; Ch. Deliso, The Coming Balkan Caliphate: The Threat of Radical Islam to Europe and the West, Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2007].

[22] T. B. Seybolt, Humanitarian Military Intervention: The Conditions for Success and Failure, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2007, 79.

[23] Ibid.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS