Views: 1272

May 12 to 14 marks the 90th anniversary of the coup by Józef Piłsudski in Poland with which the Polish bourgeoisie tried to save its rule from the threat of socialist revolution. Today, he is being idealized by large sections of the Polish bourgeoisie and the US imperialist elite.

In large measure, this is bound up with the increasing popularity of his conception of the Intermarium, a pro-imperialist alliance of right-wing nationalist regimes throughout Eastern Europe that was primarily directed against the Soviet Union. The resurgent interest in the Intermarium has been bound up with the increasing drive toward a new world war, which, as the ICFI stated in its resolution “Socialism and the Fight Against War,” has been accompanied by a revival of geopolitics among the ideologists of imperialism.

This series reviews the history of the Intermarium, the main basis of which emerged in the period leading up to World War I, as a bourgeois nationalist antipode to the United Socialist States of Europe that were proposed by Leon Trotsky.

Piłsudski and the Intermarium before the October Revolution

The Latin term Intermarium signifies “land between the seas” and is used to refer to an anti-Russian alliance of the states between the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea. Historically, this region largely coincides with the territory once controlled by the Polish nobility in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which existed from 1569 to 1791, before those territories were partitioned between the Russian Empire, the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Polish-Lithuanian Two Nations Republic

The Polish-Lithuanian Two Nations Republic

The main conception of the Intermarium was formulated by the Polish general and dictator Józef Piłsudski. Throughout the 20th century, its fate has been closely bound up with the development of the Russian Revolution.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the late 18th century before the three partitions that divided these territories between the Russian Empire, the German Empire and Austro-Hungary

The main basis for the Intermarium was formulated as early as 1904 within the context of the Russo-Japanese War and on the eve of the First Russian Revolution of 1905 by Piłsudski, who was at that point a leading member of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS).

The PPS had been founded in 1892 on the basis of a platform blending elements of Marxism with Polish nationalism. The main goal of the PPS was the achievement of national independence from the Russian Empire. In this struggle, the party regarded the non-Russian nationalities in the Tsarist Empire as its main allies. Rejecting any closer association with Russian social democracy and dismissing the possibility of a working class revolution against the tsarist regime, the PPS maintained its closest ties in Russia with the Social Revolutionaries (SRs). Like the SRs, the PPS was oriented toward layers of petty bourgeoisie and supported terrorism, rather than the mobilization of the working class. Above all, the PPS had a strong nationalist orientation and was ferociously anti-Russian.

In 1893, the Social Democratic Party of Poland (SDKP) was formed by Rosa Luxemburg, Leon Jogiches and Julian Marchlewski, largely in opposition to the “social patriotic” platform of the PPS. In 1897, the SDKP merged with the Lithuanian Workers’ Union to form the Social Democratic Party of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL). Engaged in an uninterrupted ideological struggle against the PPS, the SDKPiL sought the closest possible relations with the Russian Social Democrats, although the leadership of the SDKPiL differed sharply with the position of the Bolsheviks on the national question, rejecting the slogan of national self-determination.

When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, the two largest socialist parties of Poland were deeply divided over what policy to pursue. While the SDKPiL organized, together with the Jewish Labour Bund, anti-war demonstrations on May 1, 1904 in opposition to the imperialist war, the PPS pursued a fervently pro-Japanese line. In the hope of winning the support of the Japanese government for the creation of a Polish nation-state and the destruction of the Tsarist Empire, the PPS sent Józef Piłsudski to Tokyo. In his memorandum to the Japanese Foreign Ministry, he suggested utilizing the national tensions within Russia to destroy the Tsarist Empire. He wrote:

“This strength of Poland and its importance for a part of the nations in the Russian state give us the courage to set the political goal of destroying the Russian state into its component parts and [granting] independence to the countries that were placed by force in the [Russian] Empire. We consider this to be not only the fulfilment of our Fatherland’s cultural aspirations for an independent existence, but also a guarantee of this existence, since Russia, deprived of its conquests, will be weakened to such an extent that it will cease to be a threatening and dangerous neighbour.”[1]

The Japanese government rejected the proposal in favor of another war strategy, but Piłsudski stuck to his conception and developed it further in several publications after the defeat of the revolution of 1905. During the revolution of 1905, Piłsudski led the Military Organization, which he had formed on behalf of the PPS, in order to prepare the armed insurrection against Russian rule that the PPS was planning.

The outbreak of a general strike in Russia in January 1905 and the subsequent violent confrontations between the Russian working class and the tsarist autocracy took the PPS leadership wholly by surprise and prompted a shift to the left within its rank and file and sections of the leadership. While Piłsudski’s Military Organization was engaged in bloody battles with the tsarist troops, much of the PPS supported the general strikes in support of the Russian workers that the SDKPiL and the Bund had called for.

During the Russian Revolution, a significant amount of the strike action took place in Poland and the country was brought to the brink of a civil war. After the bloody defeat of the revolution, the PPS split into a left and right wing. After the formal expulsion of the Military Organization from the PPS, Piłsudski himself soon left the organization. In 1908, he founded the Union of Active Resistance. It incorporated the Military Organization and was designed to prepare the cadres for a future bourgeois government and the armed forces of a Polish nation-state.

The First World War found the Polish elites, the landlords, remnants of the aristocracy and the still relatively weak bourgeoisie, divided. Almost 100 years after the last partition of the country in 1815, the local elites of the partitioning zones of Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Tsarist Empire supported their respective partitioning power in the war. Piłsudski, who had maintained relations with the Austro-Hungarian General Staff for several years, quickly started to form the so-called Legions in Galicia.

While Piłsudski and his co-fighters had pinned all their hopes on Austro-Hungary and its relatively liberal nationality policy in fighting for a Polish nation state, neither Germany, Austro-Hungary’s ally in the war, nor the Habsburg monarchy itself had any intention of supporting an independent Polish nation state. For months, Vienna and Berlin engaged in vicious quarrels over who was to get what part of the territories.

The October Revolution, in which the Russian proletariat seized political power under the leadership of the Bolshevik Party under Lenin and Trotsky, radically changed the entire situation in Europe and was the single most significant event for the further development of Poland in the 20th century. The Bolshevik government soon declared that the Polish people had the right to decide about their future and the Russian troops were withdrawn from the formerly Russian parts of Poland.

While the Prussian and Austro-Hungarian governments increasingly descended into bitter infighting about who would get what part of the remaining Polish territories, German soldiers began to desert and withdraw from Poland. Inspired by the events in Russia, revolution broke out in Germany in November 1918, forcing the government to end the war and withdraw its remaining troops from what are now Poland and the Baltic States. It is under these conditions that the Entente powers, the United States, Britain and France, decided that a Polish nation state was in the best interest of European capitalism and the struggle against Soviet Russia.

Józef Piłsudski with his staff in front of the Governor’s Palace in Kielce, August 1914

Józef Piłsudski with his staff in front of the Governor’s Palace in Kielce, August 1914

The western borders of the Second Polish Republic were sealed by the Entente powers with the Treaty of Versailles of June 28, 1919, which ended the state of war between the Allies (France, Great Britain and the United States) and the defeated Germany. While not all demands of the Polish delegation were fulfilled, the Warsaw government was given control over much of Silesia and gained access, although not exclusive, to the harbour of Gdańsk. The settlement of the western borders was motivated to a large extent by the desire to curb the economic might of the defeated Germany and thus prevent a quick recovery of the German economy. The eastern borders, by contrast, were to be fought out only in the war the Piłsudski regime was soon to wage against Soviet Russia.

The Polish-Soviet War

Historically, the Intermarium federation emerged as the counter-project of the Polish bourgeoisie to Trotsky’s United Socialist States of Europe. In opposition to the federation of socialist workers’ states to unify the continent on a socialist basis, Piłsudski formulated a federative framework for the unification of bourgeois nationalist forces in East Central Europe. For the Polish bourgeoisie, which presided over one of the oldest and largest capitalist economies in the region, it was also to provide the framework for satisfying its aspirations as the leading regional power in Eastern Europe and achieve territorial expansion at the expense of Ukraine, Lithuania and what is now the Czech Republic.

However, the social and economic impotence of the Eastern European bourgeoisie, which had proven itself incapable of completing the bourgeois revolution and was faced with the socialist threat of the working class almost as soon as it was born, made this project completely reliant on the benevolence of the imperialist powers, above all the United States.

Indeed, as the coming decades would show, the prospects of the Intermarium, an idea that never left the minds of Poland’s leading bourgeois politicians and strategists, rose and fell with the strategy of world imperialism against the Soviet Union and, since 1991, the Russian Federation.

The first time the Polish bourgeoisie attempted, unsuccessfully, to create a federation along the lines Piłsudski envisioned was in the Polish-Soviet war of 1920. It is also in this period that the reactionary content of the Intermarium conception, which had been propagated as a vehicle for the achievement of the national and emancipation aspirations of the peoples oppressed by the tsarist regime, was revealed. In his attempt to realize it, Piłsudski based himself on extreme anti-communism and the mobilization of right-wing, nationalist forces in Ukraine that were as hostile to their native working class and peasant population as they were toward Soviet Russia.

Despite repeated attempts by the Bolshevik leadership to end the military conflict, the Polish-Soviet war, which had been dragging on during 1919 with numerous skirmishes and battles over individual cities, eventually escalated with Poland’s invasion of the Ukraine in the spring of 1920.

Throughout the war, Piłsudski tried to pursue his aim of establishing an anti-communist federation of nationalist governments in Eastern Europe that were to be united by their common hostility toward Soviet Russia. However, this effort largely failed. The Lithuanian bourgeoisie was hostile to a project in which it had to subordinate itself to the Polish elites and agree to a Polish-controlled Wilno (Vilnius in Lithuanian; the city, now the capital of Lithuania, was contested for centuries and during the Civil War itself between the Polish and the Lithuanian elites). The Estonian bourgeoisie was equally unenthusiastic. The only real backing Piłsudski received in the region was from the Finnish government. Poland’s most important imperialist allies, France and Great Britain, did not support Piłsudski’s plans either at that point.

After having knocked on literally every door in Eastern Europe, including that of the former tsarist general and Russian chauvinist Denikin, for whom hardly any political thought was more alien than an independent Poland, Piłsudski eventually ended up with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura, who, in the words of one historian, “could boast the least vigor and the weakest following” of all the factions active in the civil war in Ukraine. [2] Petliura’s army, which had largely been recruited on an anti-Polish platform from nationalists in western Ukraine, now passed into Polish service.

While the Warsaw Agreement with Petliura of April 21, 1920, was in part the outcome of the lack of any alternative for either side in their struggle against the Bolsheviks, the territories now comprising the Ukraine occupied a strategic position in Piłsudski’s plans for a federation. As one historian pointed out:

“With Ukraine, Piłsudski’s Border Federation had a real chance of prosperity and survival. Poland, as chief sponsor, could command a network of trade and commerce stretching from Finland to the Near East. Poland might recover the glory of her medieval past when, or so the story goes, as arbiter of a realm vaster than the Holy Roman Empire, she ruled over Cossacks and Tartars and drove the cringing princes of Muscovy to their lair. Without the Ukraine, the Border States would be so many barbs on an Allied fence.”[3]

However, the Red Army succeeded relatively quickly in reconquering Ukraine due in no small part to the anti-Semitic pogroms committed by Petliura’s armies and a general lack of support for his “People’s Republic” within the Ukrainian population. The subsequent decision, supported by Lenin but taken against the advice of many Polish Bolsheviks and Leon Trotsky, to not wait for further developments but proceed with an advance of the Red Army into Poland in order to foster the outbreak of social revolution resulted in a military and political disaster for Soviet Russia. In August 1920, Piłsudski’s armed forces successfully defended Warsaw. A few weeks later, the Red army was defeated by Piłsudski’s army. In April 1921, the Bolshevik government signed the Peace Treaty of Riga that defined the eastern borders of inter-war Poland.

Although the victory against the Red Army constitutes something of a founding myth of the Second Polish Republic and is glorified by the Polish bourgeoisie to this day, in reality, the country found itself in a deep political crisis with vicious infighting within the ruling elites, which eventually forced Józef Piłsudski to formally leave the political scene in 1922. For the next few years, which were a period of uninterrupted political and economic crisis, he remained politically active “behind the scenes.” In particular, he continued to maintain ties to numerous nationalists and military leaders from the mostly exiled, former elites of the countries that now formed part of the Soviet Union, and formed the basis of the so-called Promethean League.

American Professor Timothy Snyder (Yale University), who devoted an entire book to one of Piłsudski’s closest associates, Henryk Józewfski, described the Promethean League as follows:

“The Promethean Movement was an anticommunist international, designed to destroy the Soviet Union and to create independent states from its republics. … It brought together grand strategists of Warsaw and exiled patriots whose attempts to found independent states had been thwarted by the Bolsheviks. Symon Petliura and his exiled Ukrainian People’s Republic joined forces with other defeated patriots from the Caucasus and Central Asia. … Prometheanism was supported by European powers hostile to the Soviet Union, morally by Britain and France, politically and financially by Poland.” [4]

Eastern Europe after the formation of the Soviet Union in 1922

Eastern Europe after the formation of the Soviet Union in 1922

These policies were institutionalized and intensified after Piłsudski’s seizure of political power in the May Coup of 1926. In domestic affairs, the promotion of this anti-communist, right-wing nationalist alliance was compounded by a brutal crackdown on the communist and socialist parties in Poland and the establishment of an authoritarian regime with fascist elements.

From both a political, economic and a geographical standpoint, Piłsudski continued to regard the Ukraine, now a Soviet Republic, as the main springboard for an assault on the Soviet Union and its dismemberment.

The Polish secret service, whose upper echelons were to a significant extent recruited from military leaders who had fought alongside Piłsudski in the Legions and the Polish-Soviet War, developed extensive activities in the Soviet Union, above all Soviet Ukraine. Adherents of Symon Petliura, who himself was murdered in 1926 in Paris, and numerous Ukrainian nationalist military leaders were given political asylum.

In 1927, the army of Petliura’s wartime “Ukrainian People’s Republic” was re-founded in secret on Polish territory. Its general staff developed plans for an invasion of the Soviet Union. In 1930, when Soviet Ukraine was on the brink of a civil war because of the mass famine caused by the criminally adventurous policies of the Stalinist bureaucracy, the Ukrainian army was ready to exploit the crisis and invade the USSR. However, the Polish government ultimately rejected the proposal, most likely because of the military superiority of the Red Army, which had developed rapidly in the 1920s. [5]

Then as now, the plans for the Intermarium were developed and pursued entirely behind the backs of the Polish people. It was never proclaimed official state policy and never discussed among the parties in the open. In the words of Timothy Snyder, “Poland was too important to be entrusted to the Poles.” [6]

The Polish government built up an entire infrastructure with military and educational training for actual or prospective adherents of the Promethean network and numerous publications. This included the Institute of the East in Warsaw, dedicated to studies of the Near and Far East; scholarship programs for Promethean students in Warsaw, Vilnius, Poznan, Kraków, Paris, Berlin and Cairo; four Promethean clubs in Warsaw, Paris, Helsinki and Kharbin, and numerous journals, including Promethée (in Paris) and Prometheus (in Helsinki) that propagated and discussed ideas surrounding the Promethean movement. In addition, separate Institutes and publications were founded to discuss and promote the Promethean project in Ukraine, in relation to the Tartars, the Caucasian peoples and the Cossacks. [7]

However, during the 1930s, Piłsudski gradually lost support for his Intermarium policy in the Polish elites and military. For much of the 1930s, he tried to manoeuvre between Hitler’s Third Reich and the Soviet Union. On July 25, 1932, Poland and the USSR signed a non-aggression pact. As a consequence of this, the Polish government somewhat slowed down its activities with regard to the Promethean movement, without shutting them down, however. The centre of planning and directing was now transferred from various ministries, who had divided the work among themselves, to the Second Department of the Second General Staff. [8] In 1934, Piłsudski’s Poland concluded a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany.

Five years later, in August 1939, in a desperate attempt to prevent a war against Nazi Germany and having already murdered most of the communists in Poland, Russia and throughout Eastern Europe, Stalin struck a pact with Hitler to divide up Europe into spheres of influence in case of a Nazi assault on Poland, which then followed a few weeks later on September 1, 1939. The Intermarium during World War II

Following the invasion of Nazi Germany on September 1, 1939, the Polish government fled the country. Sections of the Intermarium network were integrated in the Reichsabwehr of the Third Reich. They were employed in the war effort against the Soviet Union, which Nazi Germany invaded on June 22, 1941. During the war against the USSR, the Nazis systematically mobilized local far-right forces, particularly in the Baltics and Ukraine, to help in annihilating European Jewry and fight the Red Army. According to one author:

“The Abwehr (German military intelligence service) used Intermarium contacts as pre-war ‘agents of influence’ abroad as well as reasonably reliable sources of information on the large émigré communities of Europe. By the time the Nazis marched across the Continent, Intermarium had become, in the words of a US Army intelligence report, ‘an instrument of German intelligence’.” [9]

Meanwhile, the bourgeois government-in-exile, which was based in London since 1940, again took up the conception of the Intermarium federation in a somewhat altered form. General Władysław Sikorski, who had been a former bourgeois opponent of Piłsudski, now picked up his ideas for a federation as the head of the government-in-exile. In a memorandum he submitted to US President Franklin Roosevelt in December 1942, he proposed the formation of a Central European Federation. This federation, according to Sikorski, was necessary in order to provide for the

“ … economic existence and, therefore, also of the security of the states along the Belgrade-Warsaw axis. A federation based on strong foundations will be a guarantee likewise of the security of the United States, both in relation to Germany and also to any other forces which might again bring Europe to a state of chaos and, consequently, of war. According to our conception, the basic elements of the federation include: Poland (with Lithuania), Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Greece (and Hungary).” [10]

However, Sikorski’s proposal was rejected. In light of the danger of a socialist revolution in Europe, which by 1943 saw growing working class struggles against the Nazi occupation, the United States, France and Great Britain agreed upon a division of Europe into spheres of influence with the Soviet Union. The Stalinist bureaucracy, in exchange, was to play the key role in blocking the emergence of a revolutionary movement by the working class.

Following the end of the Second World War, the Stalinist bureaucracy extended the property relations of the October revolution in a military and bureaucratic way to Eastern Europe. Although the Allies had agreed upon this division of spheres of influence in order to safeguard bourgeois rule on a world scale, the deformed workers’ states that emerged in the post-war period never ceased to be a thorn in the side of imperialism. In the covert warfare against the Soviet Union, the imperialist powers based themselves to a significant degree on the mobilization of those very right-wing and fascist forces that had been part first of the Intermarium and then of the Nazi war network against the Soviet Union during World War II.

Former members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) were recruited en masse by the CIA and channelled out of the Soviet-controlled zone of Europe. The same programs covered Nazi collaborators and fascists from the Baltic States (Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia), Croatia, Slovakia and other countries as well as other countries. (See: “Nationalism and fascism in Ukraine: A historical overview”)

The single most important channel was the Vatican with its close historic ties to the far-right in Eastern Europe. Sections of the Catholic elite basically merged with the Intermarium. This included figures such as Monsignor Krunoslov Draganovic, who ran escape routes for Ustashi (Croatian Fascist) fugitives, and served as the chief Croatian representative on the self-appointed Intermarium ruling council. The senior Ukrainian Intermarium representative was Archbishop Ivan Buchko, who helped free a Ukrainian Waffen SS legion by intervening with Pope Pius XII; Gustav Celmins, the former führer of the Nazi Latvian Perkonkrusts, became the secretary of the headquarters branch in Rome. [11]

The single most important channel was the Vatican with its close historic ties to the far-right in Eastern Europe. Sections of the Catholic elite basically merged with the Intermarium. This included figures such as Monsignor Krunoslov Draganovic, who ran escape routes for Ustashi (Croatian Fascist) fugitives, and served as the chief Croatian representative on the self-appointed Intermarium ruling council. The senior Ukrainian Intermarium representative was Archbishop Ivan Buchko, who helped free a Ukrainian Waffen SS legion by intervening with Pope Pius XII; Gustav Celmins, the former führer of the Nazi Latvian Perkonkrusts, became the secretary of the headquarters branch in Rome. [11]

The glue that kept together all the different alliances that the nationalists from the Promethean League underwent over the 20th century was their militant anti-communism. The Intermarium thus became one of the mainstays of Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberation from Bolshevism and many other CIA-sponsored operations during the Cold War. [12]

Most of the Polish elites and nationalist intelligentsia had left the country by 1948, when the Polish People’s Republic was proclaimed. Sections of these layers continued to promote the Promethean project. In Paris, the most significant Polish émigreé journal, Kultura, edited by Jerzy Giedroyc, openly advocated Piłsudski’s Intermarium strategy.

Giedroyc had been an official in the Piłsudski government in the years 1929-35 and in the words of the American professor Timothy Snyder, who celebrates his contribution to a revival of the Intermarium, was “a central if discreet figure of the Prometheanism of the early 1930s.” [13] Several other figures from the early Promethean movement also gathered around Kultura. A central idea of Giedroyc’s journal was that Poland could only be an independent nation state if Lithuania, Belarus, and in particular Ukraine, were also independent nation states. The journal therefore closely monitored and supported the nationalist movements in these Soviet republics. Its ideas and policy advise were to exert significant influence on sections of the Polish dissidents in the trade union movement Solidarity who later actively participated in the restoration of capitalism in Poland and its first bourgeois governments after 1989.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union by the Stalinist bureaucracy in 1991 and the destruction of the Stalinist states in Eastern Europe, the Polish state again came to play a strategic role in the calculations of imperialist strategy vis-à-vis Russia and in Eastern Europe more generally. Now, the central imperialist power to which the majority of the Polish bourgeoisie oriented itself, whatever political divisions existed over foreign policy, was the United States. Just as in the interwar period against the Soviet Union, Poland has become a central bulwark against Russia in Eastern Europe for world imperialism.

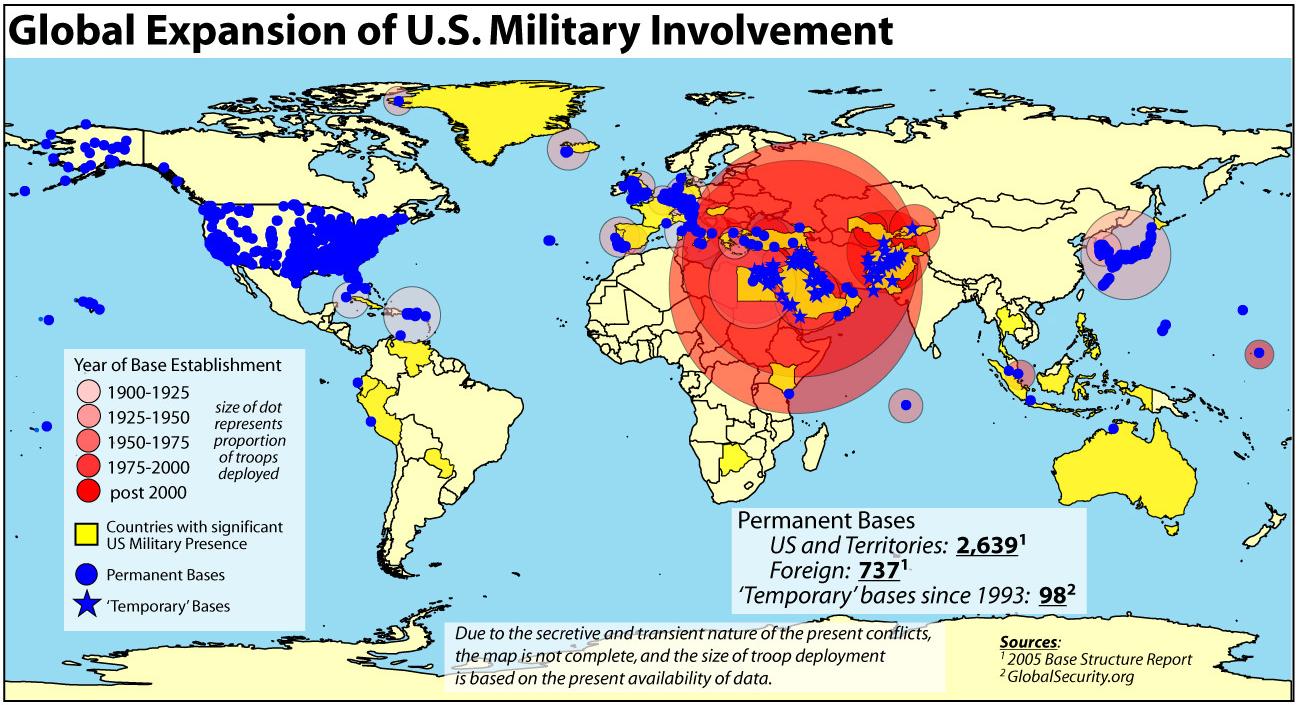

While the restoration of capitalism in the USSR and Eastern Europe opened up vast resources of labor power and raw materials to world imperialism, it has not yet brought them under its full control. Over the past quarter century, the United States has tried systematically to further encircle Russia, militarily and politically. The aim is to install a puppet regime completely obedient to Washington by a forced regime change or, if necessary, war.

As the World Socialist Web Site explained in 2004 during the unfolding “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine:

The first Iraq war in 1991 already undermined to a large extent the influence of Moscow in the Middle East. The same process took place in the Balkans following the war on Serbia in 1999. In 2001, in the context of the Afghanistan invasion, the US established military bases for the first time in former Soviet republics and emerged as a presence in Central Asia. Since then, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and to some extent Azerbaijan have allied themselves to the US. One year ago, they helped lift a rabidly pro-Western regime to power in Georgia. In Europe, most members of the former Warsaw Pact, including the former Baltic Soviet republics, have now joined NATO and the European Union. Should Ukraine now switch to the Western camp, Russia would be largely isolated.[14]

These policies were to a significant extent influenced by the conceptions of the Intermarium. Within the United States, a section of the ruling class has long advocated a revival of the Intermarium. A crucial role has been played by Polish-American policy makers, chief among them Zbigniew Brzezinski, one of the most influential figures in the American foreign policy establishment. As he himself stressed in a keynote address opening of the Center of Eastern Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in 2003, his geopolitical thinking owed much to the conceptions of the Promethean League. [15]

According to Brzezinski, the central goal of the Center at the CSIS was to reestablish ties with Poland and make use of Warsaw’s historic connections with elites throughout Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Brzezinski also maintained a correspondence with Jerzy Giedroyc from the 1960s to the 1990s and financially supported his publication, Kultura. As foreign policy adviser to the Carter administration in the 1970s, Brzezinski was one of the chief architects of the US policy to support nationalist movements in the USSR to foster its disintegration.

The work most strongly reflecting the influence of Promethean ideas is Brzezinski’s The Grand Chessboard from 1997. Echoing Piłsudski’s considerations when invading Ukraine in 1920, Brzezinski wrote:

Ukraine, a new and important space on the Eurasian chessboard, is a geopolitical pivot because its very existence as an independent country helps to transform Russia. Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire.

Further, Brzezinski formulated his strategic vision for US policy:

In the short run, it is in America’s interest to consolidate and perpetuate the prevailing geopolitical pluralism on the map of Eurasia. That puts a premium on maneuver and manipulation in order to prevent the emergence of a hostile coalition that could eventually seek to challenge America’s primacy, not to mention the remote possibility of any one particular state seeking to do so. By the middle term, the foregoing should gradually yield to a greater emphasis on the emergence of increasingly important but strategically compatible partners who, prompted by American leadership, might help to shape a more cooperative trans-Eurasian security system. Eventually, in the much longer run still, the foregoing could phase into a global core of genuinely shared political responsibility.[16]

While often fighting against significant opposition, Brzezinski has been far from alone with his ideas. According to ex-US secretary of state Robert Gates, Dick Cheney, one of the chief criminals behind the Iraq war, had intended to break up the Soviet Union along ethnic lines in 1991. Gates wrote:

When the Soviet Union was collapsing in late 1991, Dick wanted to see the dismantlement not only of the Soviet Union and the Russian empire but of Russia itself, so it could never again be a threat to the rest of the world.[17]

One scholar wrote in a recent study that just as the Intermarium was never an official policy in Poland, it has never been an official policy in the US. However, sections of the ruling establishment have been supporting it for many years. In addition to Brzezinski, this includes Madeleine Albright, secretary of state in 1997-2001, and Alexander Haig, who was secretary of state under Ronald Reagan and supreme allied commander Europe, in charge of US and NATO troops in Europe. While the US ruling class has been divided over whether or not to pursue the “Promethean project,” it has clearly helped shape US foreign policy over the past decades.

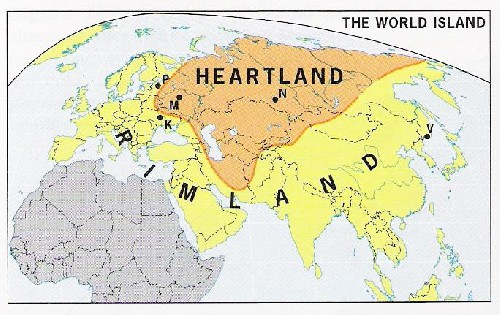

As the World Socialist Web Site has explained, the encirclement of Russia is an integral part of the US strategy for world domination, in which the territories that used to be part of the Soviet Union and the deformed workers’ state play a central role. In the language of geopolitics, they constitute largely what is termed “Eurasia,” a concept shaped by the British imperial strategist Halford Mackinder in the early 20th century. As Mackinder argued, control of Eurasia was central to control of the world. Within this framework, the states constituting the suggested Intermarium-alliance occupy a strategic role.

For US imperialism, the fate of Eastern Europe and Russia and the strategy of the “Intermarium” are subordinate to the broader goal of world domination. In order to achieve this, the so-called Eurasian landmass is considered crucial. As Brzezinski put it:

Ever since the continents started interacting politically, some five hundred years ago, Eurasia has been the center of world power. … [I]t is imperative that no Eurasian challenger emerges, capable of dominating Eurasia and thus also of challenging America.

In Brzezinski’s words,

Eurasia is the chessboard on which the struggle for global primacy continues to be played.[18]

Throughout the past quarter of a century, Poland has played a key role in implementing these policies. The US was the key driving force behind the admission of Poland and the Baltic States into NATO. It enthusiastically supported their accession to the European Union (EU), hoping, not without reason, that they would form an important pillar of US foreign policy in Europe, particularly as a counterweight to the EU’s dominant imperialist powers, Germany and France. In return, Poland has been the main pillar of NATO military expansion to Russian borders. Warsaw has supported the build-up of the nuclear missile shield that is directed against Russia and has sent troops supporting the US imperialist invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

Poland has spent more on its military than all other countries that joined NATO since 1989 combined. Poland’s drastic militarization was made possible not least of all thanks to the United States. Since 1996, the year before Poland joined NATO, the total US government military sales to the Polish government have been worth some $4.7 billion, according to a report by the Congressional Research Service from March 2016.

Moreover, Poland has been a central hub for the networks associated with the “color revolutions” in Ukraine and Georgia and for the support of the pro-Western opposition movement in Belarus. All of these movements for “democracy” are infiltrated not only by various secret services but are also closely intertwined with the local far-right movements, many of which have historic ties to the “Promethean project.”

Jerzy Giedroyc, who remained politically active throughout the 1990s and died only in 2000, has become one of the greatest influences on Polish foreign policy. In 2005, the Polish Sejm declared 2006 the “Year of Jerzy Giedroyc” and celebrated his ideas by referring to the recent US-backed “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine in 2004, which received substantial support from the Polish government. In its official resolution, the Sejm stated:

The breakthrough achieved in Polish-Ukrainian relations during the “Orange Revolution” in Kiev and the reactions of Poles to the Ukrainian struggle for the right to self-determination and democratic elections number among the Editor’s [Giedroyc’s] real and most resounding victories.[19]

When it was in government for the first time, from 2005 to 2010, the right-wing nationalist Party of Law and Justice (PiS) undertook numerous initiatives to build up military and political networks and cooperate with Ukraine, Georgia, Belarus, and the states of the Visegrad group (Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic). President Lech Kaczyński (PiS), who died in a plane crash in 2010, was well known for his aspirations to revive the Intermarium. In this, he had an ally in the Georgian president, Mikhail Saakashvili, who was brought to power by the US-backed color revolution in 2003. To underline their commitment to Prometheanism, on November 22, 2007, both presidents dedicated a statue of Prometheus in Tiflis.

Paul Globe from the Institute of World Politics hailed Warsaw’s policies in an article, entitled “Prometheanism Reborn,” writing:

First, Warsaw continues to promote democratic change and a Western rather than Moscow orientation in the other countries around the periphery of Russia. …

Second, it has become the leader of what might for want of a better term be called “the Baltic-Nordic caucus” within the West, a grouping of countries led by Poland and Estonia who want to ensure that the northeastern portion of Europe is more closely tied to the West.

And third, Poland has become even more important as a center for the study of the peoples and politics of Eurasia, not only by attracting scholars and journalists from east and west as the pre-war Promethean League did but also, again recapitulating the earlier experience, conducting research and issuing publications that are helping to define how each side views the other.

With the new right-wing government in Poland under the Law and Justice Party (PiS), the incorporation of Poland into US war plans against Russia and the realization of the Intermarium plans has reached a new level. While promoting vitriolic nationalism, Catholic bigotry and racism, the PiS government has been transforming the country into a military fulcrum that would stand at the very center of any military confrontation between NATO powers and Russia.

More so than any previous government, the current PiS government and President Andrzej Duda have put the revival of the Intermarium at the heart of their foreign policy efforts. In his inauguration address in August 2015, Duda, who maintains close ties to the head of PiS, Jarosław Kaczyński, announced that he would make the creation of an alliance among the states between the Baltic, Black and Adriatic Seas the central axis of his foreign policy. This regional bloc should eventually lead to deeper economic, political and military integration.

As has been explained above, these plans are not entirely new. However, under the government of the liberal Civic Platform (PO), these plans were put to the sidelines. While supporting a fervently anti-Russian policy, the PO government was oriented more toward an alliance with Germany. The turning point came with the coup in Ukraine in February 2014 and the simultaneous resurgence of German militarism.

After the coup in Ukraine in February 2014, the PO government increased military spending in 2015 to reach 2 percent of the total GDP in 2016. The NATO military build-up in Eastern Europe since 2014 has turned the entire region into a dangerous hotspot and possible platform for war with Russia.

A central element of the build-up has been the Obama administration’s European Reassurance Initiative (ERI) and the Readiness Action Plan, which were both announced at the NATO summit in Wales in September 2014. In 2015, US funding for the ERI totaled $985 million. An additional $789.3 million are requested for 2016. For 2017, the Obama administration has requested a quadrupling of ERI spending to $3.4 billion so as to allow for a constant presence of an army brigade in Central and Eastern Europe, as well as additional exercises and positioning of combat equipment.

In a conscious provocation against Russia, the US started Operation Atlantic Resolve in 2014 with enhanced training and security cooperation with Poland, the Baltic States, Romania and Bulgaria. Since then, numerous US military units, among them the Army’s 173 Airborne Brigade, 1 Cavalry Division and 3 Infantry Division, have participated in rotating deployments in Poland where they conducted joint military training and exercises with the Polish armed forces. The US is also planning to pre-position military equipment, including Abrams tanks and infantry, in Baltic and Central European countries, among them Poland.

However, the NATO build-up has fallen far short of the expectations of the Polish bourgeoisie. More significantly still, the Ukraine crisis brought to light increasing divisions within the NATO alliance, above all between the United States and Germany, which has become the dominating imperialist power in the EU. The latter, maintaining close economic and political ties with Russia, agreed to the economic sanctions against Russia in 2014, which amounted to economic warfare, but has consistently opposed the permanent stationing of NATO troops in Eastern Europe.

The German bourgeoisie remains divided over the policy toward Russia. Important sections, particularly the Social Democratic Party (SPD), have insisted, much to the dismay of Warsaw, that a “dialogue” with the Kremlin must be upheld. Moreover, some of the largest German companies have increased, rather than decreased, their cooperation with Russia. Most significantly, the German chemical company BASF has struck a multibillion-dollar deal with the Russian gas monopolist Gazprom in 2015. Its subsidiary, Wintershall, is participating in the preparation for the pipeline Nord Stream 2, which is vehemently opposed by both the United States and Poland. Leading politicians from the PiS have described the pipeline as a “threat to the national security” of Poland and a starting point for an anti-Polish, German-Russian alliance.

Just how much concern Germany’s continuing ties with Russia have provoked in Warsaw was revealed in a report that was jointly published by the Polish Defence Ministry and the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in 2015, entitled “Transatlantic Relations in a Changing European Security Environment.” In one of the essays, Andrew A. Michta pointed to the increasing divisions within the alliance over the policy toward Russia:

“Germany, the United Kingdom, and Italy won’t commit to anything beyond economic sanctions; France is vacillating; and the medium-sized and small states along NATO’s frontier like Poland and the Balts lack the punching power to move Europe to action.”

Further, he suggests that the Polish-German axis, with which the government of the Civic Platform (PO) has been mainly associated with, was in danger of disintegrating over these differences:

“The dream was that with Germany’s full backing Central Europe would finally escape its middle-periphery dilemma by simply being no one’s periphery. The Central European hedge rested on the assumption that Germany’s intra-regional relationships, especially its relationship with Poland, would offset its Russian Ostpolitik as a historically dominant policy vector.”

Behind the concerns over Germany’s relationship with Russia stands the more fundamental geopolitical competition between US and German imperialism. Historically, German imperialism has sought to bring Eastern Europe and the territories of the former Soviet Union under its complete control in two world wars, while fighting the United States. This fundamental conflict has been covered up since the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II, which significantly weakened the German bourgeoisie and made it dependent for a long historical period upon the support of US imperialism, not least of all in fighting the Soviet Union. However, with the re-emergence of German militarism these differences are again beginning to emerge with increasing sharpness.

This is a major reason why leading US think tanks and political analysts saw the Ukraine crisis as a confirmation of the need for a revival of the Intermarium, which has been increasingly discussed over the past five years.

Thus, Polish-American political analyst Jan Marek Chodakiewicz, who works for the Institute of World Politics, a pro-Republican graduate school for diplomats and secret service agents in Washington, argued in 2012 that the US had to focus on the Intermarium in its strategy for several reasons. The Intermarium, he argues, forms “the regional pivot and gateway to both East and West” and, in addition, is “the most stable part of the post-Soviet area (and most free and democratic).”

Therefore, Chodakiewicz advises,

“the United States should focus on solidifying its influence there to use it as a springboard to handling the rest of the successor states, including the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Russian Federation itself.”[20]

Warning of an alliance between Berlin and Moscow, he writes:

“In essence, promoting a pro-American bloc in the middle of Europe, either to complement or counterbalance the increasingly anti-American western Europe, would be indispensable to return the US influence to the old continent.”[21]

Around the same time, the late Alexandros Petersen published a book titled World Island: Eurasian Geopolitics and the Fate of the West, in which he made the case for a return to the geopolitical thinking of the British imperial strategist Halford Mackinder and the integration of Piłsudski’s Intermarium policy into US strategy for the domination of Eurasia.

These conceptions have been pushed more aggressively since the US-backed coup in Ukraine in February 2014. George Friedman, the founder and former head of the private intelligence agency Stratfor, which maintains close ties to the US military and intelligence apparatus, has repeatedly underlined the need for such a strategy. In a piece entitled “From Estonia to Azerbaijan: American Strategy After Ukraine,” he outlined his strategy for US imperialism with the following words:

“Similar to the containment policy of 1945-1989, again in principle if not in detail, it would combine economy of force and finance and limit the development of Russia as a hegemonic power while exposing the United States to limited and controlled risk. The coalescence of this strategy is a development I forecast in two books, The Next Decade and The Next 100 Years, as a concept I called the Intermarium. The Intermarium was a plan pursued after World War I by Polish leader Józef Piłsudski for a federation, under Poland’s aegis, of Central and Eastern European countries. What is now emerging is not the Intermarium, but it is close. And it is now transforming from an abstract forecast to a concrete, if still emergent, reality.”

Hinting that such an alliance would be formed in addition to NATO and perhaps eventually as a substitute, he complained that NATO was not “a functional alliance” and was divided over Russia policy. Therefore, the United States should advance the military build-up of the regimes in Eastern Europe and work for them to form a military alliance:

“The Poles, Romanians, Azerbaijanis and certainly the Turks can defend themselves. They need weapons and training, and that will keep Russia contained within its cauldron as it plays out a last hand as a great power.”

Two years earlier, at the Forum for New Ideas in 2012, Friedman had already aggressively argued for a return to Piłsudski’s Intermarium strategy before a select audience of the Polish elites. Arguing that Europe was again confronted with a resurgent Germany and a possible alliance between Moscow and Berlin, he called upon Poland to take on a leadership role in Europe. Stressing that the EU lacked the capacity to protect Poland in case of a military conflict, Friedman said:

“Poland must now depend on itself. … I will put before you a more radical idea, one that comes from General Piłsudski, the Intermarium. The Intermarium basically says: We are caught between Germany and Russia, and that stinks. … So, we must become a very difficult morsel to swallow and we can’t become that ourselves. And he proposed the Intermarium. … There are nations in Europe that survived simply because they were too much trouble to fight with. Poland must become too much trouble. But Poland must also form a free trade zone with countries who need Polish exports, need to be aligned with Poland, need to be led by Poland—Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, even Turkey. …There is a moment of leadership here that Poland can undertake—in working with the United States to create a stable environment” (emphasis in the original).

Friedman’s long-time collaborator at Stratfor, Robert D. Kaplan, stressed in a piece from August 2014 titled “Piłsudski’s Europe” that

“it is Poland and Romania, the two largest NATO states in northeastern and southeastern Europe respectively, that are crucial to the emergence of an effective Intermarium to counter Russia. Together they practically link the Baltic with the Black Sea.”

While the Intermarium was still far from being realized, Kaplan enthused,

“a trend is discernible. High-level meetings between the Intermarium countries have intensified, as the Pentagon and State Department act as hubs for all these countries’ militaries, intelligence services and diplomatic corps to interact. Stronger US support to Eastern and Central Europe must be matched by stronger bilateral ties between the countries themselves—to say nothing of increased defence expenditures in the region.”

These discussions over foreign policy within the Polish and also the US elites preceded the ascendance to power of the government of the Law and Justice Party, which is much more closely oriented toward the US and aims to revive the Promethean project. There have been three central elements of the government’s policy over the past few months that are aimed at ensuring close integration into US war plans.

First, the PiS government has dramatically stepped up the build-up of the country’s armed forces. It has lent enthusiastic support to all NATO plans for military expansion in Eastern Europe, appearing as one of the driving forces for the most hawkish proposals. Thus, Duda has long been demanding the permanent stationing of NATO troops in Poland, a proposal that is set to be discussed at the NATO summit in Warsaw in July 2016.

It also dramatically increased military spending, following the advice of George Friedman that Poland had to become “too much trouble.” The amount of military spending was increased to 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), which is well above the threshold of 2 percent of GDP demanded by NATO. Simultaneously, PiS stepped up efforts to build up a large army of paramilitary formations. The number of such paramilitary troops tripled between spring 2014 and the fall of 2015 to now approximately 80,000.

This compares to the total number of 120,000 soldiers active in the regular Polish Armed Forces. The PiS government is now integrating these paramilitary formations, which maintain close ties to the country’s virulently racist and violent far-right, into the state (see “Polish government intensifies military build-up”). Much like the guerrilla troops employed by the right-wing government in Ukraine in the civil war since 2014, these troops are aimed not only to help in case of war against Russia, but also to be deployed against the working class in case of mass demonstrations or a civil war.

Second, the PiS-government has significantly stepped up its efforts to coordinate policies with the Visegrad group (Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic), increasingly forming a political bloc of opposition toward the policies of Germany within the EU. Politically, one of the main unifying elements has been the opposition to the refugee policy of Berlin.

On a military level, discussions are underway about a possible joint military brigade between Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine, named LITPOLUKRBRIG, which, according to some analysts, could become the prototype for a joint military unit. In addition, Poland plans to form a Baltic Sea and Black Sea association, allowing countries that are not yet NATO members, like Ukraine and Moldova, to take part.

It is against this background that the third element of the PiS’s policies, the build-up of a police state, has to be understood. The massive militarization of Polish society and the military build-up are incompatible with the maintenance of basic democratic rights. Immediately following its inauguration, the PiS government has staged a constitutional coup, bringing the security services under its control. The Constitutional Court has been blocked ever since and the country’s public broadcasting services were brought under government control. With a new anti-terrorism bill and a surveillance law, the government has built up the structures of a police state. With this, the PiS government tries to secure itself against impending social and political opposition to its war policies and extreme social inequality.

However, to what extent the Intermarium alliance can and will be realized is still an open question for several reasons. First, the project is fundamentally dependent upon the support of imperialism, above all US imperialism, but there is no consensus in ruling circles in the US over this project. Second, the Eastern European bourgeoisie itself is divided over what policy to pursue vis-à-vis Russia. This goes in particular for Hungary and the Czech Republic, neither of which supports Poland’s aggressive course relating to Russia. Third, the Polish bourgeoisie itself is, as it has always been, bitterly divided over its foreign policy. While fiercely anti-Russian, supporters of the former government party Civic Platform (PO) still support a policy that is oriented toward both Germany and the United States, arguing that the Intermarium project is doomed to fail.

Nevertheless, the militarization and war strategy of the Polish government, which is working on behalf of US imperialism, must be seen as a major danger. The bourgeoisies that emerged out of the Stalinist bureaucracies and their restoration of capitalism 25 years ago are turning the region into a military fulcrum which might develop into a nuclear confrontation between US imperialism and Russia.

As in the 20th century, the Intermarium project is the geopolitical component of a policy that is aimed at mobilizing far-right forces and building up the military against the threat of a socialist revolution by the working class. The working class of Poland and Europe must oppose the bourgeoisie’s strategy of militarism and war by building a socialist anti-war movement and fighting for the unification of the continent on a socialist basis in the form of the United Socialist States of Europe.

Concluded

Notes:

| [1] | Edmund Charaszkiewicz: Referat o zagadnieniu prometejskim (12 luty, 1940) [Paper on the Promethean Question], in: Charaszkiewicz, Edmund, Andrzej Grzywacz, Marcin Kwiecień, and Grzegorz Mazur: Zbiór Dokumentów Ppłk. Edmunda Charaszkiewicza [Collection of Documents of Lieutenant Colonel Edmund Charaszkiewicz], Fundacja CDCN, 2000, p. 56. Translation by this author. |

| [2] | Norman Davies: White Eagle, Red Star. The Polish-Soviet War 1919-1920 and the “Miracle on the Vistula,”Pimlico 2003, p. 101. |

| [3] | Ibid., p. 102. |

| [4] | Timothy Snyder: Sketches from a Secret War. A Polish Artist’s Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine, Yale University Press 2005, pp. 40-41. |

| [5] | Ibid., p. 102. |

| [6] | Ibid., p. 26. |

| [7] | Edmund Charaszkiewicz: “Referat o zagadnieniu prometejskim” (12 luty, 1940) [Report on the Promethean Question, February 12, 1940], in: Charaszkiewicz, Edmund, Andrzej Grzywacz, Marcin Kwiecień, and Grzegorz Mazur: Zbiór Dokumentów Ppłk. Edmunda Charaszkiewicza [Collection of Documents of Lieutenant Colonel Edmund Charaszkiewicz], Fundacja CDCN, 2000, pp. 64-67. For many years, Edmund Charaszkiewicz was the main coordinator of the Promethean movement. |

| [8] | Ibid., p. 77. |

| [9] | Christopher Simpson: Blowback. America’s Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War, Grove Press 1988, pp. 180-81. |

| [10] | Quoted in: Sarah Meiklejohn Terry: “Sikorski and Poland’s Western Borders”, in: Keith Sword (ed.): Sikorski: Soldier and Statesman. A Collection of Essays, Orbis Books 1990, p. 139. |

| [11] | Christopher Simpson: Blowback. America’s Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War, Grove Press 1988, p. 180. |

| [12] | See Ibid., p. 89. |

| [13] | Timothy Snyder: Sketches from a Secret War. A Polish Artist’s Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine, Yale University Press 2005, p. 250. |

| [14] | Peter Schwarz, “The power struggle in Ukraine and America’s strategy for global supremacy”, 23 December 2004, https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2004/12/ukra-23d.html |

| [15] | Zbigniew Brzezinski, Inaugural Forum of the Brzezinski Chair “Strategic Issues in the New Central and Eastern Europe”, October 03, 2003, http://csis.org/files/attachments/031003_brzezinski.pdf |

| [16] | Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, 1998. |

| [17] | Robert Gates, Duty, 2014. |

| [18] | Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard. |

| [19] | “The Year of Jerzy Giedroyc – Resolution of the Sejm”, 29 July 2005, http://culture.pl/en/article/the-year-of-jerzy-giedroyc-resolution-of-the-sejm |

| [20] | Jan Marek Chodakiewicz: Intermarium. The Land Between the Baltic and the Black Seas, 2013: Transaction Publishers, p. 2. |

| [21] | Ibid., p. 391. |

Author: Clara Weiss, 2016

Source: Oriental Review

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS