Views: 1432

Preface

The European Union (the EU) is characterized by a purposeful diffusion of political authority between supranational and intergovernmental institutions. Based on the idea of shared leadership, it relies on a delicate institutional balance guarding declared equality between its ever more diverse members and managing potential and real tensions between the more and less populated states. Such tensions are present in any federal construct and have been a key concern since the ‘original six’ founded the (West) European Coal and Steel Community (the ECSC) in 1951 (the Benelux, West Germany, France, and Italy).

The formal facts and official EU’s propaganda about itself is something that we all know and we agree that is an admirable and amazing concept, that all these different people (27 Member States today) from such colorful nations decided to live together with the main purpose of having a big and united community with trying to live in peace and comfort and to enjoy the developed medical and educational systems. It is all we always read in the press and see on TV, but there were no public releases about a single wrong or questionable decision or action taken by the EU.

So, what is more, interesting now: let is have a look at some different opinions. I do not want to write about a “reality” because reality is such a subjective and questionable field, but I would like to draw the attention of a critical approach to the studies on the EU and European integration within the economic-political umbrella of the EU.

What is the EU?

All theoreticians of the European unification within the umbrella of post-WWII (West)European Communities (today the EU) will stress four crucial points of the importance of this process:

- It will bring to an end the millennial war-making between major European powers.

- A unified Europe will anchor the world power system in a polycentric structure with its economic and technological might and its cultural and political influence (probably together with the rise of the Pacific states).

- It will preclude the existence of any hegemonic superpower, in spite of the continuing military and technological pre-eminence of the USA.

- The European unification is significant as a source of institutional innovation that may yield some answers to the crisis of the nation-state.[1]

As a matter of very fact, the European unification after WWII grew from the convergence of alternative visions, conflicting interests between nation-states, and between different economic and social actors. The very notion of Europe, as based on a common identity, as highly, however, questionable. Nevertheless, the European identity, historically, was racially constructed against “the others”, the “barbarians” of different kinds and different origins (Arabs, Muslims, Turks, and today Russians) and the current process of unification is not different in this sense. The unification was made from a succession of defensive political projects around some believed common interest (for instance, the Russian “threat” after the Cold War 1.0 and especially the 2014 Crimean Crisis) among participating nation-states. The process of unification, therefore, was aimed at defending the participating countries against perceived “threats” and in all of these cases, however, the final goal was primarily political but the means to reach this goal were, mainly, economic measures. As another matter of fact, from the very start of the process of the European Unification after WWII, NATO provided the necessary military umbrella.

The European debate about competing visions of the integration process was three-folded:

- The technocrats who originated the blueprint of a united Europe (particularly the French Jean Monnet) dreamed of a federal state what practically meant the accumulation of considerable influence and power in the hands of the European central bureaucracy in Brussels, Strasburg, and Luxemburg.

- The President Ch. De Gaulle (1958−1969) emphasized the opinion concerning the transfer of sovereignty to be known as intergovernmental and, therefore, it was placing the European wide-decisions in the hands of the Council of heads of executive powers from each Member State. De Gaulle tried to assert the European independence vis-à-vis the USA and this is why France vetoed twice in 1963 and 1967 the British application to join the EEC as considering that the UK’s close ties to the USA would jeopardize the European autonomous initiatives.

- Indeed, the UK represented the third vision of European integration focusing on the development of a free trade area without conceding any significant political sovereignty. When Great Britain joined the EC (together with Ireland and Denmark) in 1973, after de Gaulle’s departure, this economic vision of the European integration (in fact, the EFTA) became predominant for about a decade.

Nevertheless, the original winning plan of Jean Monnet was from the very beginning to create a federal European supranational state – the United States of Europe into with will be merged the majority of the European nations including all the time extremely Eurosceptic Great Britain which finally left the EU (the Brexit). This new superstate popularly called United Europe will have one Parliament, one Court of Justice, single currency (the Euro), single Government (today is known as the European Council with its “Politbureau” the European Commission), single citizenship and one flag as the external attribute of the statehood. That has been the plan all along. However, those who favor it knew well that the overwhelming majority of people from Europe would never sincerely accept the European Unification in such a form. They would never willingly surrender their freedoms and national identities in order to become just a province of the European superstate as, in fact, a geopolitical project originally designed against the Soviet Union and its East European satellite states during the Cold War 1.0. So, what did the pro-European politicians in order to realize their geopolitical plan? They simply conspired to keep the truth from the people.

Now, the focal question became: What is the real truth behind the European Union?

The need to unite Europe grew understandably out of the devastation left behind after two catastrophic world wars. There is clear evidence, both in the successive European treaties themselves and in pronouncements by the would-be designers of Europe, that the European Union was intended from the outset as a gigantic confidence-trick which would eventually hurtle the nations of Europe into economic, social, political, and religious union whether they liked it or not. The real nature of the final goal – a federal superstate as the United States of Europe – was deliberately concealed and distorted. It was to be released in small doses, to condition those who would never have accepted it until it would be too late for the whole process to be reversed or crucially changed.

Brief historical background

In 1946, ex-British war PM, Sir Winston Churchill delivered his famous Zurich speech calling for the establishment of the United States of Europe but, however, his idea of united (Western) Europe excluded his native country – the UK. At that time, he envisaged West Europe of independent, free, and sovereign states that would rise from the ashes of WWII and reach for a destiny of unprecedented harmony and democracy. Neutral Switzerland, with its centuries-old harmonious co-existence of four languages and cultures (and international money laundering banks), was to be the blueprint for a multilingual and multicultural Europe which would never again see maniac dictators and supra-national demagogues bent on imposing their will on member nations.

Initially, W. Churchill’s vision seemed to be advancing according to the plan. Former Nazi Germany and fascist Italy decentralized political power and became parliamentary democracies. Nazism and fascism became discredited throughout Europe like Communism in its western part.

However, soon, the events took a different turn. The Schuman plan of 1950 proposed the supra-national pooling of the French and German coal and steel industries as a means of forging the European economic unity (the 1951 ECSC by the Treaty of Paris). The two economies were interwoven to such an extent that a new war between these traditional enemies became virtually impossible.

The European Economic Union (the EEC), established in 1957 by the Treaty of Rome, brought Italy and the three Benelux countries into the closer union with France and Germany but represented a further step towards a pan-European economy by tying economic development to the city of Rome.[2] Significantly, the Treaty of Rome also gave Europe a sense of supranational religious unity and the Roman Catholic Church the protection against the existent threat of the spreading of Communism outside of East-Central Europe.

1962 was the year of the Common Agricultural Policy resulting in the creation of a common market (transformed in 1993 into the European Single Market – the ESM) with price-fixing – a further step towards economic uniformity and, basically towards the command economy which was at the same time so heavily criticized by the Western liberal democracies in the cases of the economies of the so-called real socialism. Nevertheless, in the same 1962, year, some Western technocrats recognized the EEC as a project that is already much behind simply and economically united Europe with the comments that fascism in Europe is about to be reborn in respectable business attire, and the 1957 Treaty of Rome will finally be implemented to its fullest extent. Some of them shared the opinion that the dream of a medieval Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (962−1806) is returning to power to dominate and direct the so-called forces of the Christian mankind of the Western world. Simply, such an idea was not dead yet but still stalks through the antechambers of every national capital of continental Western Europe, in the determination of the leaders in the common market to restore the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation with all what that means.[3] Surely, West Germany, constrained in its international role and influence after 1945, saw the European unification as a very convenient international platform to pursue its own foreign policy.

Nevertheless, the word “economic” was ominously dropped from the official title of the community in 1967 in favor of the description of it just as the European Community (the EC) meaning that the integration process is now directed toward political direction what was clearly seen in 1979 when the first direct elections to the European Parliament in Strasbourg have been organized. Even the former European Assembly was renamed into the European Parliament in order to stress a clear direction toward the creation of a supranational political entity – state.

The policy of enlargement continued with Greece joined in 1981, and Spain and Portugal in 1986, when in the same year the Single European Act was signed to prepare the EC for the transformation into the EU – a higher level of economic, financial, social, legal, legislative, and above all political integration. In other words, the Single European Act meant the gradual transfer of executive, legislative, and judicial powers from the Member States to the central authorities of the EC and since 1993 of the EU. Consequently, the EU could make ever-increasing political inroads into the national sovereignty of the Member States and the London-Dublin conspiracy attempted to force the British people of Northern Ireland by stealth and terror towards a united Ireland under the European rule, while arrogant and spineless politicians in Westminster continued politely to play the enemy’s game, or, as Dr. Paisley once put it metaphorically, to “feed the brute instead of slaughtering it”.

When the (in)famous Maastricht Treaty on the European (political) Union was signed in February 1992 (to come into force in November 1993) with the ultimate aim of transforming the EC into a federal superstate – now significantly redesigned as the European Union (EU) – many of the politicians elected to Brussels, including those from Great Britain, fell for the confidence trick.

How Great Britain fell for a confidence trick

Two decades earlier, in the 1960s, when Great Britain twice sought entry into then the EEC/EC, the historian Sir Arthur Bryant had issued an unheeded warning:

“Once in the common market, we shall be a minority in an organization in which the decisions of the majority will have the power to bind the minority, not only for a few years but theoretically for all time.”

Sir Arthur Bryant could not have chosen a more apt word than “bind”. Although Great Britain was twice saved from her own folly by the French President Ch. de Gaulle in the 1960s, however, in 1973 she not so much joined as bound herself to the common market, and agreed to be bound by the 1957 Treaty of Rome.[4] Even at that time, the founders of the common market knew – but apparently Great Britain did not – that the common market (today the European Single Market) was not a club to join or a free trade area (the EFTA) with which to associate, but a superstate in the making. Its founders were in no doubt about this, even if the British politicians were unaware of – or unwilling to face up to – the ultimate goal of the founders. Robert Schuman, while preparing the European Coal and Steel Community in 1950, had said:

“These proposals will build the first concrete foundation of the European Federation”.

Article 189 of the 1957 Treaty of Rome is quite clear about what was involved:

“Regulations […] shall be binding in every respect and directly applicable […].” “Directives shall bind any Member State […].” “Decisions shall be binding in every respect […].”[5]

Unfortunately, no more people read the 1957 Treaty of Rome than had read Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf before WWII (after the war it was too late), and many who should have known better-accepted assurances that no loss of sovereignty was involved in acceding to the EEC. Looking back, we can just regret that they did not know better about the issue. After a quarter of a century, during which the EEC became transformed firstly into the EC and then the EU, experience ought to have taught us what the anti-marketers failed to teach.[6]

We can read, for instance:

“Initially I thought like everybody else, that we had joined a common market, and what could be nicer and more friendly and sensible and economically wised to do, but since then in 1975 when we had the vote to remain in that, so we were told, it has become something more than a common market, it than became, a few years later, a European Economic Community than a European Community, it’s now the European Union, with all kinds of controls and restrictions, regulations and we are faster approaching by this new Constitution, something that the French have already named potentially the United States of Europe and I am not at all sure that that’s what I and many others voted to join back in 1975”

[Delphine Gray-Fisk, retired airline pilot, a British citizen].

“We have lost one hundred percent control over our environment including health and safety regulations, we have lost near enough hundred percent control over our fishing, we have lost hundred percent control over our farming and we have lost hundred percent control over our trade policy and that last is of particular significance when you consider that Britain is the 4th largest economy in the world and we do more trade than any other country in the world, by far”

[Linsday Jenkins, author].

“So, what are the MEPs [Member of the European Parliament] for? Well, I will tell you, the MEP’s are here to vote and to vote often and to vote regularly, sometimes we vote up to 450 times in the space of 80 minutes. Now I have to confess, I do not know what is going on half of the time, I have not either read all of the documents, so massive, are they. Now it can be, that my fellow MEP’s down there are all Albert Einsteins and all absolutely understand what is going on, but I suspect that is not the case, in fact, it is rather like paying monkeys – because what happens is the civil servants draw up the lists and if it is vote No. 58 and the piece of paper say VOTE, YES you VOTE YES and if it is No. 59 and it says to VOTE NO you VOTE NO, it is an absolute false, it is a complete masquerade democracy”

[Nigel Farage, the MEP, the UK Independence Party, later the leader of the Brexit].

“We are now living under a legal order. The 1972 European Communities Act was a one-off, not an ordinary treaty, but a new way of life. These are new constitutional powers. The British Parliament surrendered its sovereignty in 1972. European laws have overriding force with priority over our British laws… The articles on the supremacy of the British parliament are now only historical perspective – they are non-binding”

[Judge Morgan.]

The plot to destroy the sovereignty of the Member States

What is the real nature and purpose of such kind of united Europe? It can be easily claimed that behind the respectable European mask is, in fact, a plot with the ultimate aim to destroy the real sovereignty (independence) of its Member States and to re-align the whole balance of power worldwide.[7] It should be remembered that, strategically, Europe’s unification drive began at a time when the entire Atlantic Alliance was coming to grips with the relative decline of the United States both as a world economic power and as leader of the West. The European Union (the EU, est. 1992/1993) with its central motor, the French-German axis, became a new GP in global politics. Therefore, the USA is not anymore in a position to dictate and implement global policies like at the time of the Cold War. After the creation of the EU, the US administration seeks a multilateral action with the EU in several hot-spot areas of the conflicts in Europe as, for instance, ex-Yugoslavia or Ukraine.

America’s generosity to the world has reduced her riches and necessitated a serious reassessment of her global strategic commitment. Trade frictions between the US and West Europe have long been a reality and have moved from the agricultural sector into advanced technological areas. Doubts also grew about the reliability of the US “nuclear umbrella” protecting West Europe, and a subsequent reduction of the American forces and the withdrawal of the Russian forces on the Continent followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union has been paralleled by increasing calls for a solely European self-defense capability. The European army and the European police force already exist in more than embryonic form.

It has to be noted that for centuries it has been the British most basic right to vote in one hundred percent of the members of Parliament who govern their country or vote them all out if they do not perform.

“For instance, the basic principle that you can elect a new parliament and then you can have a new law, that is the call of the democracy and this call does not exist in the EU and it does not exist in the Constitution we are building now”

[Jense Peter Bonde, Danish MEP].

The European unification as an umbrella for recovering of Germany as a Great Power

The Germans have had the idea that they are the inheritors of the medieval Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and as such, they should try to rule Europe, it has going on from centuries and it still exists today right up to WWI, after Otto von Bismarck and WWII, from the Kaiser of WWI to Adolf Hitler in WWII. The same idea has dominated all through German history, that they are entitled to the right of full power over Europe and all Europe should be under their sway and they still think in the same direction today, especially being vehement power in the European Union. Here, it has to be clearly stressed: unified Germany after 1989 became once again a Great Power (GP) in global politics under the mask of the European Union!

Meaning of the term Great Power(s) (GP) in global politics from the beginning of the 16th century onward refers to the most power and therefore top influential states within the system of the international relations (IR). In other words, the GP are those and only those states who are modeling global politics like Portugal, Spain, Sweden, France, the United Kingdom, united Germany, the USA, the USSR, Russia, or China. During the time of the Cold War (1949−1989), there were superpowers[8] as the American and the Soviet administrations referred to their own countries and even a hyperpower state – the USA, after the Cold War as it is called in the academic literature.[9] A focal characteristic of any GP is to promulgate its own national (state’s) interest within a global (up to the 20th century European) scope by applying a „forward“ policy.

A term global politics (or world politics) is related to the IR which are of the worldwide nature or to the politics of one or more actors who are having a global impact, influence, and importance. Therefore, global politics can be understood as political relations between all kinds of actors in politics, either nonstate actors or sovereign states, that are of global interest. In the broadest sense, global politics is a synonym for a global political system that is „global universe of actors such as nation-states, international organizations, and transnational corporations and the sum of their relationships and interactions“.[10]

After Germany was defeated in WWII, nobody thought that they stood much chance of recovery but they had a leader still, he was called Strauss and was a wise German of his day who thought that they have already tried war – three times and they were defeated each and every time, the last time – the worst of all, so he sought that in the European unification formation at that time a solution for the German getting back in both European and global arena was a right way. In other words, the umbrella of the European unification could provide for the post-war West Germany two benefits: 1) the unification, and 2) a Great Power (GP) status.

Nevertheless, what are the crucial characteristics of the GP? Originally, in the 18th century, the term GP was related to any European state that was, in essence, a sovereign or independent. In practice, it meant, only those states that were able to independently defend themselves from the aggression launched by another state or group of states. Nevertheless, after WWII, the term GP is applied to the countries that are regarded to be of the most powerful position within the global system of IR. Those countries are only countries whose foreign policy is „forward“ policy and therefore the states like Brasil, Germany or Japan, who have significant economic might, are not considered today to be the members of the GP bloc for the only reason as they lack both political will and the military potential for the GP status.[11]

One of the fundamental characteristics and historical features of any member state of the GP club was, is, and will be to behave in the international arena according to its own adopted geopolitical concept(s) and aim(s). In other words, the leading modern and postmodern nation-states are „geopolitically“ acting in the global politics that makes a crucial difference between them and all other states. According to the realist viewpoint, global or world politics is nothing else than a struggle for power and supremacy between the states on different levels as the regional, continental, intercontinental, or global (universal). Therefore, the governments of the states are forced to remain informed upon the efforts and politics of other states, or eventually other political actors, for the sake, if necessary, to acquire extra power (weapons, etc.) which are supposed to protect their own national security (Iran) or even survival on the political map of the world (North Korea) by the potential aggressor (the USA). Competing for supremacy and protecting the national security, the national states will usually opt for the policy of balancing one another’s power by different means like creating or joining military-political blocs or increasing their own military capacity. Subsequently, global politics is nothing else but just an eternal struggle for power and supremacy in order to protect the self-proclaimed national interest and security of the major states or the GP.[12] As the major states regard the issue of power distribution to be fundamental in international relations and as they act in accordance to the relative power that they have, the factors of internal influence to states, like the type of political government or economic order, have no strong impact on foreign policy and international relations. In other words, it is of „genetic nature“ of the GP to struggle for supremacy and hegemony regardless of their inner construction and features. It is the same „natural law“ either for democracies or totalitarian types of government or liberal (free-market) and command (centralized) economies.

It was a change of strategy from the aggressive war to the long-term friendly approach so that people begin to think that they are now nice people and they will gradually listen to their conversations and fall for their compliments. In that way, they will make that the French who historically hated the Germans will begin to like them, and that is exactly what happened with the process of the European unification after WWII. Instead of becoming aggressive as usual, the Germans went the other way so they finally were accepted by the French in the European Union as the leaders of further unification, they succeeded to develop the friendship with France, and the Germans and the French have been hand in hand in the EU ever since. However, behind such German-French reproaches were the creation of Germany as a new global GP as, in fact, the political, economic, and financial leader of the EU.

Germany from the very beginning of the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation (962) has always seen through every ruler, every leader the idea to conquer Europe by different means, but the ideas went further and that is why today they are not satisfied with the European unification as it stands – the European Union. Germany is trying to impose a new Constitution for the EU, which eventually if accepted by all the Member States will turn them into unitary units with no sovereign power of their own, no freedom, no law of their own, no parliaments of their own, they will become units of a superstate ruled over by Germany and France as its client state which does not really understand that French is only a tool in the hands of the Germans in their historical geopolitical projects of hegemony over Europe.

But Germany, could not have done such global geopolitical projects on their own, it was not sufficient money even to start WWI, the Kaiser was financed partly by the American banks. Furthermore, money from America, from the American-German sources, helped A. Hitler come to power, and one of the major’s families mentioned is the wealthiest in America – the Rockefellers, facts are that associate the family for helping A. Hitler to finance WWII, so the association of ideas is not just to turn Europe into a superstate, but for America to do the same and become from a democratic country a superstate which eventually will join up Europe to create a world superstate for building one global Government having the most powerful and richest persons in the world as its leaders.

After every war, it is normal for every country to disarm but Germany never disarms. After WWI there was signed a treaty which forbidden Germany to have more than 100.000 men armed but what was not known was that Germany made secret assignments with the Soviet authorities in 1921−1922 and they had an agreement signed in Italy whereby, the Soviet Bolsheviks would allow Germany to build arms, build factories, trainman, build an army with the condition that also trained the Soviet Bolsheviks, so this army was trained in the 1920s when all the European countries were disarming themselves.

A Franco-German axis

An Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) is the formal procedure for negotiating amendments to the founding treaties of the EU. Under the treaties, an IGC is called into being by the European Council and is composed of representatives of the Member States, with the European Commission, and to a lesser degree the European Parliament which as well as is having participation.[13] However, the functioning of the IGC has long been provided by a real leader of the EU that is a Franco-German axis although its strength has historically varied and its nature seems to be changing. This did not differ much in the case of the 2002 Convention on the Future of Europe, partly because it did not replace the IGC as an institution and, in fact, it took place in the shadow of the following IGC, i.e., the veto power of the Member States. It is, therefore, no surprise that the bargaining space, i.e., the set of settlements potentially acceptable to the Convention on the Future of Europe, were bounded by the positions and bottom lines of the most powerful Member States and that the very salient issues were firmly kept under their control. Once concrete issues were put on the table, the representatives of the national Governments loyally defended their interests – as did most of the national MPs nominated by the Governments. By the autumn of 2002, they started to build coalitions and invoke their veto in the pending IGC. The other members, anticipating the IGC, adapted their behavior to this constraint.

Not only did the Member States take the lead, at the same time the MPs were largely ineffective. The political parties were unable to develop coherent visions and positions, except in a few specific instances, for example, related to symbolic ideological gains (ex.: the “social market economy” for the socialists). But the big parties only had a superficial unity and on most issues were unable to overcome their divisions and build coalitions beyond the status quo. For most representatives, the party’s political or component identity was not the primary determinant of their positions in the Convention on the Future of Europe. They saw the role of the party’s groups as channels to exchange information rather than forums to coordinate positions.

Thus, the Convention on the Future of Europe was overall – particularly in institutional and policy issues – not radically different from the IGC and much of its end-game was dominated by the kind of hegemonic compromises that have characterized EU’s politics since its inception.

The Franco-German “Dual EU’s Presidency”

The Franco-German compromise was put forward by the two countries on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of their bilateral friendship (Élysée) treaty in January 2003. Shortly before presenting their joint institutional proposals, in October 2002, France and Germany had replaced their Government’s representatives with their Foreign Ministers increasing their political weight in the Convention on the Future of Europe. Germany did not defend the rotating Presidency but sought to strengthen the power of the European Commission. Although the Franco-German compromise was not formally put on the agenda of the Convention on the Future of Europe it generated widespread opposition and immediately became a focal point for subsequent debates. The contribution included the controversial creation of what became referred to as a “Dual EU’s Presidency” with a permanent European Council, the President elected from amongst its members, and a directly elected Commission President by the EP. The permanent Chairs would also be created for Foreign Affairs, Ecofin, the Eurogroup, and the Justice and Home Affairs (the JHA).

From the outset, France and Germany relied upon a number of resources that were instrumental in turning its proposal into the focal point. First and most importantly, they found a crucial ally in Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (the President of France in 1974−1981) who reacted favorably calling their compromise “a positive proposal [that is] going in the right direction (…) guaranteeing the stability of EU’s institutions”. He was personally much closer to the Franco-German compromise than to the Benelux proposals and sensitive to the British position which – while supporting the permanent European Council Presidency – was initially skeptical about the election of the European Commission President. His detractors recalled the fact that he had become the Chair of the Convention on the Future of Europe on the insistence of J. Chirac, T. Blair, and a German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder. In addition, he “created” the European Council in 1974 and would, therefore, naturally want to make it the apex of the European system. They pointed out, furthermore, that this dual presidency set-up resembled the peculiar French political system in which the President is the “leader of the nation” and the “ultimate arbitrator of the national interest”, while the Prime Minister heads the Government. Finally, they argued that his two foremost goals have been to support the claims of big countries and to weaken the European Commission. His defenders, in turn, retort that this only appeared to be the case because he tried to ensure that “his” Constitution would not be radically altered by the IGC, and therefore the most powerful Member States. Whatever the motivation, at some point before the official tabling of the draft articles on institutions, he chose to take sides and to support the idea of a permanent European Council Presidency.

V. Giscard’s and the Presidium’s support were crucial because its composition, functions, procedural control, and operating style gave it the necessary legitimacy and influence to shape the final outcome of the Convention on the Future of Europe. V. Giscard had ample room for maneuver. During the first three months, the members were invited to present their views on the EU and listen to civil society associations. On this basis, V. Giscard presented what he called an issue-specific “synthesis” reducing the scope of the discussion, and set up working groups on controversial topics to study the subject in-depth. Finally, after the reports of the working groups had been discussed in plenary sessions, the Presidium presented actual draft articles to the Convention on the Future of Europe which was supposed to mirror the substance of working group reports and reactions of the plenary sessions. Members then suggested amendments leading to revised proposals by the Presidium. But, crucially, while the Convention on the Future of Europe was supposed to remain sovereign in this process, the Presidium acted as the interpreter of the dominant view and was the sole drafter of the actual text presented to the floor. V. Giscard fully exploited his formal and informal powers assuming the major directing and leadership role. As D. Allen finds, he “monopolized reporting of the work of the Convention to both Member States and the public”, “it was usually Giscard’s or Kerr’s summary of proceedings that formed the ongoing basis for further negotiation”, and he cleverly “created controversies (…) or negotiating positions that were designed to be conceded in return for consensus on more important items”.[14] In fact, it was V. Giscard who determined that no voting would take place in the Convention on the Future of Europe, that a single text would be agreed rather than options proposed, how consensus and the majority were to be defined, and when a consensus existed. This gave him much leverage to steer the result towards his most preferred option. Crucially, as his definition of consensus rested essentially on the Member States’ population size rather than the number of the Member States, the Franco-German compromise was guaranteed a dominant position in the drafting process.

The UK’s and Spain’s support of a permanent European Council President (they advocated an even stronger President than the Franco-German compromise did it) was a second key resource. In addition, Italy supported a strong “Mr. Europe”.[15] Once onboard, the countries which supported the idea of a permanent Presidency represented the largest part of the European population – as V. Giscard pointed out in various interviews. Before the plenary, he argued that the EU now comprised three categories of states:

- The four largest ones, with a population of more than forty million inhabitants each, which, together, amount to 74% of the EU population.

- Eight medium-sized countries, with a population between 8 and 16 million people each, which represent 19% of the population.

- Eleven small states which, together, only include 7% of the population.

Some weeks later, at the Athens European Council, he explicitly drew the consequences of this analysis: since those who reject the idea of a permanent President for the European Council only represent a quarter of EU’s total population, they should not be allowed to prevent the formation of a consensus (which in V. Giscard’s mind seemed to mean a very large majority). With such an argument, V. Giscard contradicted the principle of equality among conventioneers he had supported so far.[16]

It is also noteworthy that Spain was amongst the Presidium’s three Government’s representatives. So was Denmark, which was the only country not to join the small country camp in their defense of the rotating Presidency. In addition, it proved difficult for the smalls to split the big country coalition promoting the permanent Presidency. Thus, the big country camp remained strong – the only wedge appeared on the European Commission’s composition when Spain and Poland, joined quietly by some new members, started waging a “give Nice a chance” campaign towards the end. This position later explained the difficulties of the IGC and the failure of the December 2003 Brussels Summit.

A third resource on which the Franco-German axis could rely was its past reputation and legitimacy. As F. Cameron argues, the EU as a whole has usually reaped beneficial results from the Franco-German initiatives – a prominent example being the European and Monetary Union (the EMU).[17] Particularly, Germany had in the past frequently defended small state interests and the legitimacy of the Franco-German compromise was enhanced as – apart from the Presidency – it contained important elements that were in line with small state suggestions. The election of the European Commission President by the European Parliament, for example, reflected Benelux’s suggestions and had broad support in the Convention on the Future of Europe. Crucially, the British position evolved in this regard. Apparently, its traditional opposition to replacing the European Commission’s President chosen by the Member States with an elected one could be traded off against the “strategic prize” of a stronger leader representing EU’s Governments on the world stage. As Peter Hain, the British Government’s representative put it to his Parliament:

“in the end, there will have to be an agreement and a necessary process of adjustment by all parties. We have, for example, been willing to look at, with certain very big safeguards, electing the Commission President through some method, provided that does not involve being hostage to a particular political faction and provided that the outcome is one that the Council can accept. So it is not something we sought and we remain deeply skeptical about it, but if, as part of the end game, getting an elected President of the Council, which is very much a priority for us, involves doing something with the Commission President with those very important safeguards that I mentioned, then that is something that we might have to adjust to”.[18]

Moreover, a consensus had emerged on the double-hatted Foreign Affairs Minister as included in the Franco-German proposal and supported in the autumn by a narrow majority in plenary even if the precise division of tasks (in particular in terms of external representation) between the European Council’s President and the proposed European Foreign Minister in charge of the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy were unclear under the Franco-German plan and remained so in the Convention on the Future of Europe’s draft treaty.

To sum up, the strategy on which France and Germany relied upon was fourfold:

- Uniting their resources to provide direction in the Convention over the EU’s future institutional set-up.

- Fully exploiting its positional resources such as access to and support by the Convention’s Chairman and its Presidium in order to move its proposal into the dominant position.

- Bringing the UK and Spain on their side.

- Inducing the smalls to make concessions on the permanent Presidency in return for an elected European Commission President and the Minister of the European Foreign Affairs.

Euro-pessimism

In the 1970s, the process of the European integration experienced the first waves of the pessimistic feelings of the citizens during the 1973 and 1979 economic crises due to three focal reasons:

- Most of the European nations felt deprived of political power by the two superpowers – the USA and the USSR.[19]

- The European Community (the EC) was technologically outclassed by the development of the information technology largely beyond the European shores.

- Economically lagging behind not only the USA but as well as new Asia-Pacific competitors (Asian Tigers of South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and today by China).[20]

The economic pessimism became shortly softer in the next decade when the inclusion of Greece (1981) and particularly Spain and Portugal (1986) added breathing space to the EC’s economy but at the same time, the enlargement of these three southern countries also added economically depressed regions, and complicated negotiations in key areas like agriculture, fishing, labor legislation, and voting procedures. In the mid-1980s, it was the feeling that the EC and Europe, in general, could become an economic and technological colony of the American and Japanese companies and, therefore, it led to the next major defensive reaction by Brussels – reaction to globalization.

Toward the superstate of the European Union

As a matter of counter challenging the process of globalization, the leaders of the EC decided to go further with the creation of a superstate within a form of the European Union (the EU) and, therefore, as the first legal action to lead toward such political aim it was signed the Single European Act (the SEA) in 1987. It had two focal tasks: 1) an economic, to set up steps toward the constitution of a truly unified market by 1992; and 2) a political, to pave the basement for the creation of the EU. Simultaneously, economic measures have been combined with an emphasis on technological policy. As an example, the European wide Eureka program was established at the initiative of the French President F. Mitterrand. The program was aimed at counteracting the American (and Japanese to a certain point) technological onslaught that came to be symbolized by the Star Wars program.

As an ideological framework of a newly rising European superstate, an artificial European supranationality became widely supported by Brussel’s bureaucracy and leading European politicians as, for example, F. Mitterrand who was softening the French position against the idea of the pan-European identity. Working side by side with France, the Spanish Felipe Gonzales was supporting the German emphasis on the pan-European political institution of the administration of a superstate. There were three major results of such policy:

- Broader powers are given to the European Commission (the executive body of the European Council).

- The European Council (the Government, representing heads of executives) obtained majority voting procedures in several key domains (no veto right anymore!).

- The European Parliament received some limited powers, beyond its previously very symbolic role but still not being a real legislative institution, which brings the law as it was rather the European Council.

For the Spanish, Portuguese, and Greek democrats, a strongly unified democratic Europe would prevent their countries from returning to political authoritarianism and cultural isolation. In fact, there was a double impulse to the transformation of the EC into the EU in 1992/1993: 1) South Europe (Portugal, Spain, and Greece) became politically democratic; and 2) France and Germany were defending the techno-economic autonomy of Europe in the global system with the price of the creation of a superstate of the EU.

Measure to further political integration was, however, economic one: the establishment of a truly common market for capital, goods, services, and labor. Nevertheless, the basic results have been: 1) Ceding parts of national sovereignty; and 2) ensuring some degree of autonomy for the Member States at the time of globalization. The British PM M. Thatcher (1979−1990) tried to resist, retrenching the UK in state-nationalism but, finally, such policy cost her job as at that time most British political and economic elites believed in the opportunity represented by a unified Europe within the political framework of the EU.

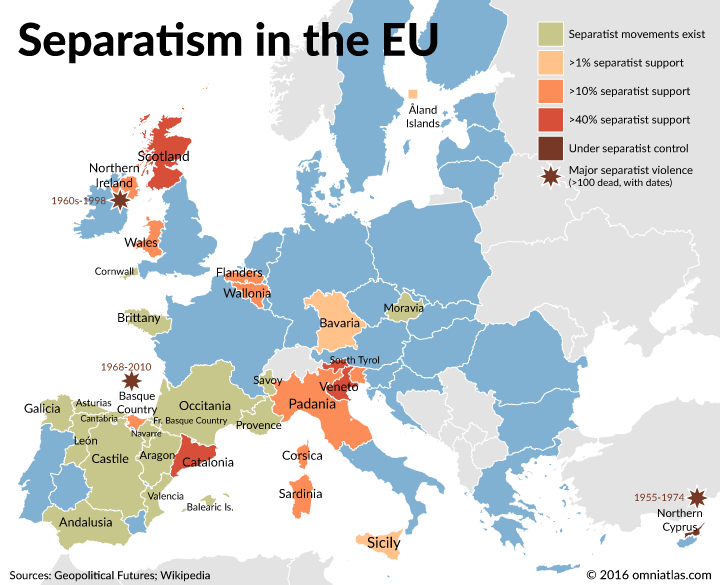

A new geopolitical environment

The European geopolitical environment became drastically changed in 1989 and 1990 as the German unification on November 9th, 1989 (legalized by the German Constitution in 1990) changed a balance of powers and prompted another round of the European unification, however, together with the destruction of three multinational states around: Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and the USSR. On one hand, the unification of Germany (in fact, the annexation of the territory of the DDR by the FRG) affected deeply the unification of Europe but on other hand, it infected the separatist movements across Central, South, and East Europe including as well as the Caucasus and provoking the bloody civil wars.[21] Here, we have to remind ourselves that the neutralization of geopolitical tensions between Germany and its European neighbors (primarily France and Poland) was the original short-term goal of the post-WWII European unification. However, unified Germany after 1989, with some 82 million people, is annually participating with around 30% of the EU’s GNP.[22] In other words, unified Germany became a most decisive force within the EU as the end of the Cold War 1.0 allowed Germany to be truly independent and, therefore, it became imperative for Europe to strengthen the economic and political ties with Berlin on one hand, but on other hand, Europe has to be afraid of both German historical revisionism and the policy of Realpolitik.[23]

Full integration of the German economy with the rest of the EU’s Member States came with: 1) The introduction of a single European currency – Euro (€); 2) The Creation of an independent European Central Bank (with the HQ in Germany in Frankfurt (M)). However, the main compensations to Berlin to sacrifice solid Deutschemark (DM) and the Bundesbank were:

- The European institutions would be reinforced in their powers, moving toward a higher level of supranationality.

- Consequently, in such a way, it was overcoming traditional French resistance, and British rejection, to any project approaching federalism.

- The Enlargement of the EC/EU toward the north and east (a new Drang nach Osten policy of Berlin).

The push toward further European integration (the EU) and its enlargement was the only way for Berlin to start projecting Germany’s weight in the international arena. Japan, contrary to Germany, however, was not ever able to bury the specters of WWII. Nevertheless, West Germany did it via its full participation in supranational European institutions, as well as in NATO. The EU’s enlargement was and is one of the most strategic geopolitical goals of Germany’s foreign policy for the realization of historical German imperialistic aims in Europe. In the case of the enlargement with Austria, Sweden, and Finland (1995), the focal goal was to balance the EU with richer countries and more developed economies in order to compensate for the inclusion of South Europe (Greece, Spain, and Portugal), with its burden of poor regions. However, in the case of East Europe (2004, 2007, 2013), united Germany via enlarged Europe is trying to play its traditional role of a Central and East European (Mitteleuropa) dominant political, financial, and economic power but without being suspected of reconstructing Otto von Bismarck’s (1862−1890 in office) imperial dream of Drang nach Osten followed by Adolf Hitler as well.[24]

Russophobia

Russophobia became unofficial but quite visible post-Cold War 1.0 policy of both the NATO and the EU what means that all potential new Member States have to accept and implement it as an ideological precondition for the membership. East European countries whose Governments decided to join these two Western organizations, put all kinds of pressures on Germany to join the EU and the USA to join the NATO. However, differently from West European countries, all of the East European candidate states have firstly and mandatory to join the NATO and then the EU. Official Russophobic propaganda had the same cliché: it was done fundamentally for (quasi)security reasons as in their public discourse it was necessary in order to escape from the Russian influence in the future – a syndrome of the fear from Russia. A leading EU’s country – Germany – supported their case intending to establish a territorial buffer zone between its eastern borders and Russia – a new Cordon Sanitaire (the old one was established by France after WWI).[25] However, Russia does not seem to represent a security threat to the West especially in the 1990s when it was the subordination of the Yeltsin Government to Western influence and when the state of the Russian military, and economic conditions of the country, did not allow Russian foreign policy to project ambitions of geopolitical power in Europe but at that time the NATO experienced its first post-Cold War enlargement with East European countries which at the same time sought the EU’s membership too. Quite contrary, the NATO but not Russia showed in 1999 its aggressive and imperialistic face of a global gangster by attacking the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to create a mafia (quasi)state of Kosovo in 2008.[26] Germany used well both the NATO’s and the EU’s umbrellas to project its colonial policy in the Balkans from 1999 onward. Russia is, nevertheless, one of the oldest European cultures which historically several times experienced the Western invasions and occupations including and by those East European countries who joined both the NATO and the EU after the Cold War 1.0 (for instance, Poland and Lithuania).[27]

Problems with enlargement

The enlargement of the EU to the East creates, however, and greater difficulties for effective integration in the EU. The real reason is the vast disparity of economic and technological conditions between the Western Member States of the EU and its new members from the East. From the very administrative point of view, the truth is the larger the number of members, the more complex the decision-making process exists which, in fact, is threatening to paralyze the EU’s institutions reducing the EU to a free-trade area (like EFTA) with a weak degree of political integration and massive burden of the Brussels professional-political bureaucracy.

Nevertheless, these problems and challenges, in fact, have been the focal reason why the UK supported the process of enlargement: The larger and more diverse the membership, the lower the threat to national sovereignty! However, there was a paradox of seeing the FRG (the most federalist country) and the UK (the most anti-federalist country) supporting enlargement of the EU for entirely different reasons. As a matter of fact, all new eastern Member States have their economies deeply penetrated by the European investment but mainly German that is, in fact, an economic German Drang nach Osten after 1989. All of them are as well as largely dependent on exports to the EU and mainly to Germany. Ultimately, the enlargement of the EU toward the East is forcing reform of its political institutions but and Brexit too.

The Maastricht Treaty and superstate

The reform of EU’s political institutions basically started from the very beginning of the EU herself: by the Maastricht Treaty – signed on February 7th, 1992, and came into force on November 1st, 1993. The reform brought by the Maastricht Treaty was to a great extent a preparation for the eastward enlargement. The Treaty was revised in the Intergovernmental Conference held in 1996−1997, after the Danish and French referenda, and British parliamentary opposition threatened to reject it. The Maastricht Treaty reflected the compromise between different interests concerning the issue of the European supranationality. The focal Maastricht Treaty’s decisions were: 1) The introduction of the common Euro currency; 2) The establishment of the European Monetary Institute; and 3) The harmonization of fiscal policies. The process of economic and political integration in the EU was confirmed in December 1996 by the Stability and Growth Pact reached in Dublin.

By these focal decisions, the Maastricht Treaty made an irreversible commitment to on one hand a fully integrated economy of the EU, but on another had to the creation of the European supranational superstate. Therefore, those decisions have been followed by the reinforcement of the decision-making power of the European institution: 1) Making it more difficult to form a blocking minority vote in the European Council; and 2) The European-wide policies began to take precedence over national policies with the ultimate result that national states lost their significant part of political sovereignty.

The first challenges to common foreign policy and security

Political integration of Europe into a superstate was symbolized by the change of official name from the European Community to the European Union with the final political task to create the United States of Europe. However, in the 1990s, foreign policy, security, and defense were not truly integrated as they had to be according to the Maastricht Treaty. In other words, there were different EU’s policies towards the Yugoslav civil war in 1991−1995 followed by the Kosovo War in 1998−1999. It was the catastrophic management of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1992−1995 by the EU which gave NATO credibility to assert itself as the fundamental security instrument of the EU in close alliance with the USA. However, the final words concerning the settlement of the conflicts on the territory of ex-Yugoslavia have not been of the EU but rather of the USA.

The election of a Spanish Socialist leader, Javier Solana, to the post of Secretary-General of the NATO in December 1995 symbolized political and military coordination of policies of the EU and the USA. He will become later in October 1999 (after the bombing of Serbia and Montenegro) Secretary-General of the European Council. Nevertheless, Ch. de Gaulle’s dream of a European military and strategic independence vis-à-vis the USA was over, and truly speaking, the UK and Germany never wanted this independence. As a result, the EU became deeply dependent on the USA in strategic terms. The 1998−1999 Kosovo War showed the dependence of the EU on NATO as the indispensable military tool of its foreign policy. It is obvious that for technological and geopolitical reasons the EU’s defense system will still operate in close coordination with the USA. The focal reasons why the USA is the indispensable partner of the EU’s defense policy are its technological superiority and the willingness to use its taxpayer’s money to pay for superpower status in global politics. Nonetheless, since 1999, the USA is a key node in a complex network of strategic decision-making of the EU’s foreign and security policy.

Final remarks

The European integration after 1945 has been based on a sophisticated concept of shared leadership to manage its inherent tension between large and small countries – a trait the EU shares with all federal experiences. Three mechanisms, in particular, preserved the basic principle of equality among the Member States, while giving to the larger ones a preponderant role:

- The system of weighted votes in the European Council.

- The role and composition of the EU’s supranational institutions.

- The rotating Presidency.

Successive enlargements have made these mechanisms ever less adapted to the functioning of the European Union. As the number of small states has grown much more rapidly than the number of large states, the institutions which guaranteed equality among states have seemed less defendable to the larger ones. By the time the Convention on the Future of Europe was convened, a new bargain was needed to reconcile the principles of equality among states and proportional democratic representation in the EU.

It is known that Germany always wanted to dominate over Europe and it is a fact in our days that united Germany is the ruling power of the European Union which is just giving the umbrella for Berlin’s traditional projects of a Mitteleuropa and Drang nach Osten from the time of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation up to the European Union.

Finally, the post-WWII policy of the European unification was passing the path from several European Communities to the EU with the ultimate geopolitical task for the near future to establish the United States of Europe.

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

[1] Featherstone K., Radaelli C. M., The Politics of Europeanisation, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2003; Cini M., European Union Politics, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2004.

[2] In fact, there were two Treaties of Rome signed on March 25th, 1957: 1) Creating Euratom, to coordinate policy in nuclear energy, the new strategic industry; and 2) Creating the European Economic Community, oriented towards improving trade and investment but as well as towards further political steps in the creation of the European superstate.

[3] See more in [Professor Arthur Noble, “The Conspiracy Behind the European Union: What Every Christian Should Know”, Lecture delivered at the Annual Autumn Conference of the United Protestant Council in London on Saturday, November 7th, 1998].

[4] In 1973, Great Britain together with Ireland and Denmark became Member State of the European Community.

[5] Sir Arthur Wynne Morgan Bryant (1899–1985), was an English historian, a columnist for The Illustrated London News, and man of affairs [Wikipedia].

[6] See more in [M. J. Artis, Frederick Nixson, The Economics of the European Union: Policy and Analysis, 2001.

[7] A concept of sovereignty refers to a status of legal autonomy (independence) that is enjoyed by states what means in practice that the government has sole authority within its borders and enjoys the rights of the membership of the international political community. Therefore, the terms of sovereignty, autonomy, and independence can be used as synonyms.

[8] The term superpower was originally coined by William Fox in 1944 for whom such a state has to possess great power followed by great mobility of power. At that time, he argued that there were only three superpower states in the world: the USA, the USSR, and the UK (the “Big Three”). As such, they fixed the conditions of Nazi Germany’s surrender, took the focal role in the establishing of the UNO and were mostly responsible for the international security immediately after the WWII [Martin Griffiths, Terry O’Callaghan, Steven C. Roach, International Relations: The Key Concepts, Second edition, London−New York, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2008, 305].

[9] China, with its enormous economic and man-power potentials followed by its rising military capability, will soon emerge as the most influential GP in global politics overtaking a role of a sole hyperpower from the USA. The 21st century is already a century of China but not of the USA as it was the 20th century.

[10] Richard W. Mansbach, Kirsten L. Taylor, Introduction to Global Politics, Second edition, London−New York: Routledge, 2012, 577.

[11] Israel is the only exception from this definition as this state has as its “West Bank” the USA. In other words, when we speak about the USA in IR, we speak de facto about Israel and the Zionist lobby in the USA.

[12] The European Union (the EU, est. 1992/1993) with its central motor, the French-German axis, became a new GP in global politics. Therefore, the USA is not anymore in a position to dictate and implement global policies like at the time of the Cold War. After the creation of the EU, the US administration seeks a multilateral action with the EU in several hot-spot areas of the conflicts in Europe as ex-Yugoslavia or Ukraine.

[13] Wikipedia.

[14] D. Allen, “The Convention and the Draft Constitutional Treaty”, F. Cameron (ed.), The Future of Europe, London: Routledge, 2004.

[15] The Guardian, January 24th, 2003.

[16] About the general issue of European politics, see more in [Maria Green Cowles, Michael Smith, The State of the European Union, 2000].

[17] F. Cameron (ed.), The Future of Europe, London: Routledge, 2004, 12.

[18] Peter Hain, Interview in the European Affairs Committee of the House of Commons, March 25th, 2003.

[19] The term superpower was originally coined by William Fox in 1944 for whom such a state has to possess great power followed by great mobility of power. At that time, he argued that there were only three superpower states in the world: the USA, the USSR, and the UK (the “Big Three”). As such, they fixed the conditions of Nazi Germany’s surrender, took the focal role in the establishing of the UNO and were mostly responsible for the international security immediately after the WWII [Martin Griffiths, Terry O’Callaghan, Steven C. Roach, International Relations: The Key Concepts, Second edition, London−New York, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2008, 305].

[20] China, with its enormous economic and man-power potentials followed by its rising military capability, will soon emerge as the most influential Great Power in global politics overtaking a role of a sole hyperpower from the USA. The 21st century is already a century of China but not of the USA as it was the 20th century.

[21] See, for instance [Moorad Mooradian, Daniel Druckman, “Hurting Stalemate or Mediation? The Conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, 1990−1995”, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 36, No. 6, 1999, 709−727; Jelena Guskova, Istorija jugoslovenske krize 1990−2000, I−II, Beograd: IGA”M”, 2003; Shale Horowitz, “War after Communism: Effects on Political and Economic Reform in the Former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia”, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2003, 25−48].

[22] Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total sum of goods and services that is produced by one state in a given year but not including goods and services that are produced abroad by domestic individuals or companies. Gross national product (GNP) is a total value of all goods and services produced by a country in a year, whether within the state’s borders or abroad. Gross national income (GNI) is measuring the market value of goods and services which are produced during a certain period (usually within one calendar year) and provides an estimate of a state’s total agricultural, industrial and, commercial output.

[23] This is a German term that became widespread from the time of the German Chancellor (PM) Otto von Bismarck. The term means in IR studies a cold calculation of a state’s national interests regardless of the human or moral aspects of its realization. The term is usually understood as an essence of Realism theories on global politics based on “ruthlessness” [Jeffrey Haynes, Peter Hough, Shahin Malik, Lloyd Pettiford, World Politics, New York: Routledge, 2013, 713]. Realism is a political view that operates with power as the fundamental point of politics claiming, therefore, that international politics is in essence power politics behind which is a principle of Realpolitik. The advocates of Realism argue that international politics is a struggle for power for the sake to deny other states the capacity to dominate. Subsequently, a balancing of power became a central concept in IR developed by the realists. If there is a single world hegemon, global politics is going to be just a struggle between the GP in seeking both political, military, economic, financial, etc. domination and preventing other states or actors from dominating [Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki, Steve Smith (eds.), International Relations Theories. Discipline and Diversity, Third Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 59−93]. Nevertheless, in a global struggle for power, Realpolitik is an unavoidable instrument for the realization of national goals what means that the use of power, even in the most brutal way, is quite necessary and understandable as it is an optimal means to accomplish foreign policy’s aims. That was, for instance, clearly expressed in 1999 during the NATO aggression on Serbia and Montenegro (from 24th of March to 10th of June) which included very much German forces as well.

[24] See more in [P. J. Katzenstein (ed.), Mitteleuropa Between Europe and Germany, Providence−Oxford, 1997].

[25] Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, London−New York: Routledge, 1999, 407−516. About the relations between Russia and the EU, see in [Срђан Перишић, Нова геополитика Русије, Београд: Медија центар Одбрана, 2015, 234−245].

[26] Hannes Hofbauer, Eksperiment Kosovo: Povratak kolonijalizma, Beograd: Albatros Plus, 2009; Пјер Пеан, Косово: „Праведни“ рат за стварање мафијашке државе, Београд: Службени гласник, 2013.

[27] See, for example [Ignas Kapleris, Antanas Meištas, Istorijos egzamino gidas: Nauja programa nuo A iki Ž, Vilnius: Briedis, 2013; Jevgenij Anisimov, Rusijos istorija nuo Riuriko iki Putino: Žmonės. Įvykiai. Datos, Vilnius, Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2014].

Originally written for and published on Oriental Review in July 2020.

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS