Views: 1138

The Warmongers

The war, which began in August 1914 – to contemporaries the Great War, to posterity the First World War – marked the end of one period of history and the beginning of another. Starting as a European war, it turned in 1917, with the entrance of the US into a world war. The spark that triggered it off was the assassination of the Austrian heir-presumptive, Archduke Franz Ferdinand (1864−1914), by a Bosnian nationalist of Serb origin – Gavrilo Princip[1], a member of the Young Bosnia (Mlada Bosna) movement, in Sarajevo on June 28th, 1914 on his official visit to administrative centre of Bosnia-Herzegovina – the province that was illegally annexed by Austria-Hungary in October 1908 by breaking the decisions of the 1878 Berlin Congress. What is today the proponents of revisionist historiography hiding from the discourse is a very fact that the Austrian-Hungarian authorities did everything to directly provoke Serbs in this province for the sake to have formal casus belli for the aggression on neighboring Serbia. Therefore, Vienna organized a massive military exercise on the very border with Serbia to be attended by a warmonger Archduke F. Ferdinand[2] exactly on the holiest day of Serbian history – the Kosovo Battle on June 28th (1389).[3]

Nevertheless, speaking about the July Crisis of 1914, one fact is for sure clear: Serbia did not want the war especially not immediately after two Balkan Wars against the Ottoman Empire (in 1912−1913) and Bulgaria (in 1913).[4] Based on a fake propaganda that Serbian government in Belgrade organized the assassination in Sarajevo and backed by Berlin, Vienna and Budapest declared the war to Serbia on July 28th, 1914 by a regular telegram.[5] However, who really wanted the world war in summer 1914 was a German Emperor, who was at the same time and a genuine master of Austria-Hungary’s foreign policy. It was exactly Berlin to officially proclaim war to Russia on August 1st, 1914 by sending a telegram to Sankt Petersburg at 5:45 am.[6]

It is a very fact that the discussions about direct responsibility for the outbreak of the Great War involved many contemporaries from the very beginning of the war. Germany’s government already on August 3rd, 1914, for the sake to whitewash its own responsibility, issued a White Paper – a collection of documents “proving” Germany’s innocence.[7] However, even many German researchers are considering this compilation as “the biggest lie” about the outbreak of the Great War.[8] The Austrian-Hungarian officials and press have been all the time putting all responsibility for the war on Serbia and her government accusing them for a direct organization and realization of the Sarajevo’s assassination.[9] On another side, nonetheless, the voices were much more realistic, as, for instance, by Charles Vopicka:

“The world war began in the Balkans but its real origins should be sought in the intentions of unscrupulous autocrats, whose brutal ambitions recognized no justice and no limits, continuing on submission of free nations only as an initial step in ‘the game’ for achieving economic and political supremacy and, ultimately, domination of the world. Serbs were but ‘the initial spark’ that triggered and had to be used mercilessly, to remove the first obstacle standing in the way of conquering the world”.[10]

The New German Order in Europe

According to German historian Fritz Fischer, one of the crucial far-long designs of Germany’s policy at the end of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century was the creation of Central Europe (Mitteleuropa), as a new economic unit controlled by Germany. How the New German Order in Europe would be organized one can understand from the conception of the Middle European Tariff Union designed in Bethmann- Hollweg’s program in September 1914 which divided Old Continent into two parts:

- The territories considered as direct members of the system: (France, Luxembourg, Denmark, Netherlands, Belgium, and Russian part of Poland), followed by Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary.

- The countries considered as the associates of the system: (Norway, Sweden, and Italy).

However, in 1916 the new territories were designated for annexation by Germany: Lithuania with Vilnius and Courland with Mitau. At the same time Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, the Ottoman Empire, and Greece were seen as incorporated lands into the New German Order in Europe under the direct administration by Berlin. Finally, Livonia, Estonia, and Finland were designed for a closer political and economic alliance with Germany after the peace treaties of Brest-Litovsk and Berlin.[11] At such a way, the Yugoslav territories of Austria-Hungary were intended for a direct membership, while Serbia and Montenegro were considered for the incorporation into the New German Order in Europe as the separate parts from the other Yugoslav territories. Nevertheless, all Yugoslav territories were designed as the parts of German Mitteleuropa – a new unite under German political control and economic exploitation. However, German-dominated Europe, and basically the rest of the world as well, is a geopolitical concept which dates back when Europe discovered, dominated, and exploited the world with the center of such Eurocentric approach of globalization based in Central Europe and Germany. It is clearly presented for the first time on the map of Europe and the world by Gerardus Mercator in Germany in 1569.[12]

The German geopolitical imperial plans in Europe became very popularized in German-speaking territories during the Great War when Friedrich Naumann published the book Mitteleuropa. The author basically drew up a plan for a federal union in Central Europe that aimed at incorporating West Russia, Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. In practice, this plan was realized by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 3rd, 1918). Formally, such geopolitical designs were inspired by the conviction that political-economic rivalry with the US, the UK, and Russia required Germany to enlarge the space under its own geopolitical control as a fourth global state by the establishment of close links with Central and East Europe (enlarged Mitteleuropa).[13] It was explained that such design would create a flexible international political order, marked by a spirit of political compromise, in which different nations would be able to coexist in peace. However, in practice, this was crass imperialism designed with the geopolitical purpose to cement German power in Europe.[14] The authorities of Austrian-Hungarian Danube Monarchy (both in Vienna and Budapest) accepted participation in Germany’s schemes for the creation of German-controlled Central Europe (Mitteleuropa) – the Central European Customs Union.[15]

The Balkans and Mitteleuropa

What both Germany’s and Austro–Hungarian governments understood, what concerns the question of the Balkan incorporation into the Central European Customs Union and a geopolitical space of Mitteleuropa, was that in this part of Europe their crucial enemy was the Kingdom of Serbia, which sought to be united with its ethnolinguistic compatriots from the oppressive Austro–Hungarian Empire, what practically meant a dissolution of Austria-Hungary. Serbia was, at the same time, seen as the main obstacle against the Austrian and German (a pan-Germanic) political-economic penetration towards the Aegean Sea (Thessaloniki), and even further towards the Middle East (the so-called project of Drang nacht Osten or Berlin-Baghdad connection).[16]

Among all European crises and conflicts at the end of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century the rivalry between the Kingdom of Serbia and the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary was a unique one. According to Joachim Remak, “the concept of a Greater South Slav State was fully as defensible as was Austria-Hungary’s right to survival”.[17] Further, according to the same author, the Austro–Serbian struggle originally (as it was imagined in Vienna and Berlin) had to be finished in the form of the third Balkan war, as the war between “the two nations directly affected…”[18] From Germany’s perspective, the Austro–Serbian military clash had to be isolated from the influences from the rest of the European powers.[19] From the Habsburg perspective, the Austro–Hungarian declaration of the war against Serbia (July 28th, 1914) was intended to reassert the position of Austria-Hungary as an independent European Great Power.[20] According to Joachim Remak, “Berchtold and Conrad had very much of a premeditated desire for a simple Balkan war to recover some of the monarchy’s lost prestige”.[21] In other words, the realization of Germany’s geopolitical concept of Mitteleuropa in the Balkans would regain a status of Great Power to the Danube Monarchy at the European scene. However, after the Balkan Wars, enlarged Serbia became the crucial obstacle for the realization of such aims while Bulgaria was seen in both Berlin and Vienna as the fundamental ally.

Bulgaria’s war aims

Bulgaria’s policy of a hegemony in the Balkan Peninsula since 1885 dovetailed with the political and military aims designed by the Central Powers, particularly with an intention to eliminate Serbia as a political factor in the Balkans. After the failure of Bulgarian aims in the Second Balkan War (1913), Sofia found a support from the Central Powers for its aim to incorporate both Vardar (Serbian) and Aegean (Greek) Macedonia.[22] Therefore, following the outbreak of the WWI, on August 2nd, 1914 Bulgaria’s Radoslavov’s government offered to the Central Powers a political-military alliance in return for Bulgarian participation in the war against Serbia with the intention to gain territorial concessions (similarly what later Italy offered to the Entente in 1915 – to fight on the side of the Entente for the territorial concessions in the Balkans and South Tyrol). The government in Sofia insisted that Bulgaria had to annex all territories on which Bulgaria put claims based on the “ethnic and historical rights” of Bulgarians.[23] Bulgarian western territorial pretensions were not in opposition to the Austro–Hungarian plans with regard to the territorial concessions at the expense of the Kingdom of Serbia. Rather, the plans about the creation of a Greater (San Stefano) Bulgaria (from March 1878) were fully in accord with the Balkan policy of the Danube Monarchy. The Austro–Hungarian ruling circles agreed that the Kingdom of Serbia has to be territorially reduced to the extent which would no longer be dangerous for the Danube Monarchy, but at the same time opposed the annexation of larger territories populated by the Serbs in order not to have so huge number of the South Slavs (and the Slavs in general) within the Dual Monarchy. That was a crucial reason for the Central Powers to accept the Bulgarian territorial aspirations at the expense of Serbia.

By signing the Secret Convention on September 6th, 1915 with Bulgaria, the Central Powers guaranteed to Bulgaria an annexation of the whole territory of East Serbia as far as the Morava River and the whole portion of Serbia’s Vardar Macedonia.[24] According to this convention, Bulgaria gained the territories of the Kingdom of Serbia as far as the demarcation line between Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary, which was stretching from Smederevo, between Kruševac and Stalać, before Vučitrn and Prizren, including the Šara Mt., Lakes of Ohrid and Prespa and the town of Gevgelia on the south.[25] According to the first article of the Secret Convention, Bulgaria should be enlarged with the new 51.425 square km. and 2.648.168 inhabitants.[26] Finally, according to the same convention, Bulgaria should achieve from the Ottoman Empire the territory of the lower Maritza River in front of the city of Edirne.

The main dispute between Serbia and Bulgaria during the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century was about the question of Macedonia. The problem was so complex that even Russian ambassador in Belgrade during the WWI (1914–1917), Count Grigorie N. Trubecki, admitted that he never could reach a right conclusion on Macedonia, although he studied this question for the long period of time.[27] The Russian diplomacy was, in general, indulgent towards the Bulgarian territorial requirements. For instance, during a meeting with the Bulgarian ambassador in Serbia, Tchaprashnikov, in November 1914 in the city of Niš in Serbia, Count Trubecki informed him that “Bulgaria may achieve Macedonia”, but regarding the Balkan territories annexed by Romania and Greece after the First Balkan War “we can only promise that You will be supported by us”.[28] G. N. Trubecki, as well as, indicated that Bulgaria might annex the territory of Thrace as far as the line Enos-Midia. However, the Russian ambassador in Serbia at the same time noticed that Bulgaria would gain these promised territories only in the case if Sofia will enter the war on the Entente side.[29] The Russian diplomacy, likewise the diplomacies of other member states of the Entente, from the very beginning of the war, pressed Serbia to revive the Balkan political-military bloc of 1912 and to make a final bilateral settlement with Bulgaria upon a territorial division of Vardar Macedonia.[30] As a territorial compensation for Serbia’s lands handed over to Bulgaria, Russia offered to Serbia doubtful territorial concessions: “…except pure Serbian lands and concessions on the other side”.[31] However, Serbian answer always had been that the bloc could be recreated again, but with a remark – the required territorial concessions had to be given to Bulgaria by Greece and Romania, but not by Serbia. At the same time, Serbia claimed that the question of the South Slavs had to be resolved by their union into one common national state and that Vardar Macedonia had to be included into Yugoslavia too.[32] It is obvious that from the very beginning of the war, the crucial war aim of Serbia was a creation of a large South Slavic state in the Balkans. The question of inclusion of Bulgaria into Yugoslavia primarily depended on the Bulgarian diplomatic decision which military bloc (the Central Powers or the Entente) Sofia will join.

Serbia’s war aims

Serbia’s war aims during the WWI were designed within the framework of two options. Their realization depended only on the issue of the result of the war and the attitude by the victorious Great Powers to the geopolitical arrangement of the post-war Balkan affairs. These two possible options were:

- The first one, and more realistic, was an option of the unification of all Serbian “historical and ethnic territories” into the unified national state of all Serbs living on both sides of the River Drina. In other words, after the war, and under appropriate international political circumstances it should be created a Greater or United Serbia as a national state of all ethnolinguistic Balkan Serbs. That was an original and natural Serbia’s war aim. The first step in the realization of this option or a project was a territorial enlargement of the Kingdom of Serbia after two Balkans Wars (1912–1913), when Serbia gained Kosovo, Metohija, North Sandžak (Sanjak) and Vardar Macedonia. According to this option, an independent state of the Kingdom of Montenegro would join a Greater Serbia only voluntarily, what, in practice, happened on November 26th, 1918.[33]

- However, the second option, only accepted in the case that the first one could not be realized primarily because of the opposition by the Great Powers (what practically happened at the end of the war) was more important for the subsequent history of the Balkans and its inhabitants in the 20th Namely, Belgrade accepted the mid-19th century an idea of Yugoslavism by Austro-Hungarian Croats what practically meant the creation of Yugoslavia, or in other words a common state of the South Slavs, but with a final and forever exclusion of Bulgaria (as the causer of the Second Balkan War). That was an artificial war aim of Serbia promulgated during the whole WWI as a minimal compensation to the utopian first option. The second aim was going to be realized only if both Balkan military and an international diplomatic-political situation at the end of the Great War would be lesser suitable for the realization of the first and more natural option. Nevertheless, the creation of Yugoslavia in 1918 (in fact, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes) was, practically, an Austro-Hungarian political victory over Serbia.[34]

For Serbia’s authorities, behind the realization of the alternative idea of the Yugoslav unification was, in fact, a realization of the prime political task – the unification of all Balkan Serbs. However, the unpleasant price of the realization of second Serbia’s war aim was a post-war life in a common state with Austro-Hungarian South Slavic Roman Catholics (Slovenes and Croats) who committed terrible war crimes in West Serbia in 1914 in Austro-Hungarian uniforms, being as well as occupiers of Serbia from 1915 to 1918.[35]

One of the first pre-WWI war diplomatic steps done by Serbia’s authorities in order to get an international support for the realization of the 1844 Serbian national program[36] was at the beginning of 1912 when a Memorandum, written by the order of Serbia’s Regent Aleksandar Karađorđević (of the Montenegrin origin by birth)[37] and sent to the Russian Emperor Nikolai II Romanov. In the memorandum, Serbia’s authorities asked for the Russian support for the sake of the realization of Serbian national program in the coming Balkan wars. It was stressed the importance of the Serbs for both Russia and the Slavic world – a fact which was put on the first place in this memorandum. The Christian Orthodoxy was, according to the memorandum, the crucial link between the Serbs and the Russians and the main national marker of both nations. The Serbs, historically, after the Russians and Russia are the strongest defenders of the Christian Orthodoxy within the Slavic community in which they have a significant role in the Slavic struggle against the pan-Germanic imperialism. Finally, the memorandum stresses that a creation of unified Serbian state, consisted of Serbia, Montenegro, part of historical-geographical Macedonia (Vardar Macedonia), Ancient Serbia (Kosovo, Metochia, Raška/Sandžak), Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Croatia (including Dalmatia and Slavonia) with 10 million Slavic inhabitants would be an important political-military factor in Europe, and what is most important, it would be a significant pillar and supporter of the Russian pan-Slavic policy in Europe.[38] A united Serbian state would finally stop further Germanic penetration to the Near and the Middle East. At the same time, the Balkan Peninsula would be ultimately put under the Slavic domination.[39] On another hand, Serbia was for Russia of an extreme importance as the only Balkan state, according to the memorandum, on which Russia could rely upon. Namely, Bulgaria was more and more under the Austro–German influence through the personality of the Bulgarian King Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg, who was of the German origin; Greece was put as well as under the strong Germanic control through Greece’s dynastic connections with the German nobility and the Germanophile policy of King Constantine I, while Turkey was already under a total German political-financial control. For those reasons, Serbian national and war aims had to be supported by Russia for the sake of its own political interest in the Balkans. Finally, the memorandum concludes that a Greater Serbia would be for Russia “the last bulwark against the West”.[40]

During the first days of the Balkan Wars in 1912–1913, Serbia’s Regent Aleksandar I addressed his army with the words that it came a moment to finish the process of liberation and unification of all Serbs, a process which started with the First Serbian Uprising against the Turks (1804–1813).[41] He precisely marked, at the very beginning of the WWI, Serbian lands which have to be liberated and unified with Serbia and Montenegro in his Proclamation to the soldiers of Serbia’s army: Bosnia, Herzegovina, Banat, Bačka, Croatia, Slavonia, Srem and Dalmatia.[42] Obviously, for him, all Austro–Hungarian Christian Orthodox South Slavs belonged to the ethnic community of the Serbdom.[43]

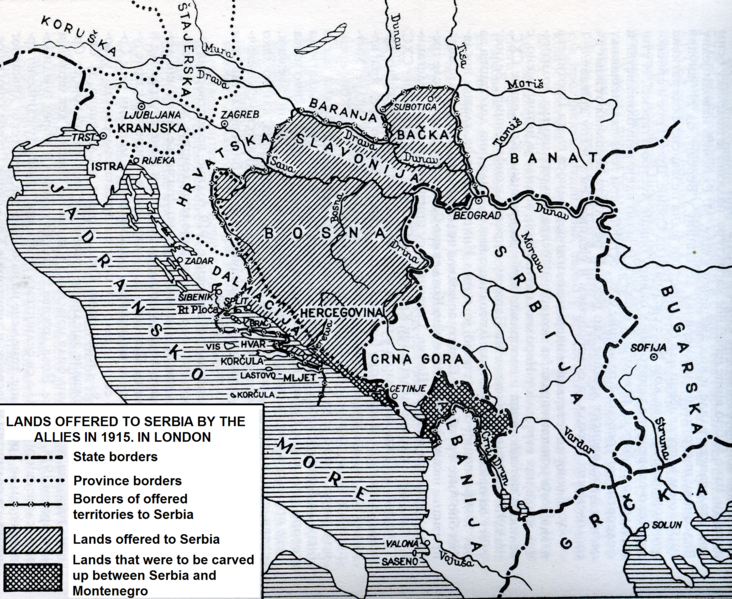

Following the idea of pan-Serbian unification, Serbia’s Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Nikola Pašić, presented his own vision of the new (Yugoslav or unified Serbian) state to his the most closed political associates on July 29th, 1914 – an idea that should be realized during the war. Namely, on the question asked by Jovan Cvijić with regard to the new boundaries with Austria-Hungary after the war, N. Pašić answered that “our borders are going to be set up on the line Klagenfurt-Marburg-Szeged”.[44] The first official act issued by Serbia’s government in which the Yugoslav program is presented, as Serbia’s maximal war aim, was N. Pašić’s Circular Note, sent on September 4th, 1914. In this document, it was emphasized that at the Balkan Peninsula, a strong national (Yugoslav) state has to be created, composed by all Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes[45] (but not Bulgarians). According to N. Pašić, the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes were a single nation, who, on the basis of their history, language, literature and the rights to self-determination, had all conditions to create their own independent state.[46] This Circular Note also emphasized that such a state would represent a single ethnic and economic region with a unified people of the same national background.[47] At the end of September 1914, N. Pašić sent to all Serbian ambassadors in the capitals of the Entente states a map with very clearly marked territorial boundaries of the future Yugoslav state, after the defeat of Austria-Hungary. N. Pašić anticipated that this state would have approximately 12 million Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes and about 230.000 sq. km. It has to be noticed that in the case of the annexation of Trieste and Klagenfurt the “first” Yugoslavia would be territorially bigger than the “second” Yugoslavia, which was created after the WWII.[48]

The Yugoslav program, as the maximal war aim of Serbia’s government, was recognized as a legitimate and official one on the session of the People’s Assembly of Serbia (the Parliament) in the city of Niš on December 7th, 1914.[49] The principal result of the assembly’s session was an adoption of the Declaration of Niš that publicly presented Serbia’s war aims to the Entente.[50] The fact is that Serbia’s Prime Minister understood the creation of Yugoslav state as the best “secondary” option in order to finally resolve the “Serbian Question” at the Balkans (i.e., to politically unite all Serbian population and lands into a single state) but only in the case that the “prime” solution (the creation of only a pure pan-Serbian national state – a Greater Serbia) cannot come true.[51] This declaration especially stressed that Serbia’s war efforts for the independence are at the same time and the efforts for the liberation and the unification of “all our not free brothers, the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes” (i.e., the South Slavs who lived in Austria-Hungary).[52] Nevertheless, the 1914 Declaration of Niš presented the integral Yugoslav program as an official war program of the Kingdom of Serbia. On another hand, the principal shortcoming of the declaration was the fact that only one side – the Royal Serbian Government – announced it. The Declaration of Niš was delivered to the diplomatic representatives of the Entente states – France, the UK, and Russia, who have been at that time together with the Royal Serbian Government in South Serbia’s city of Niš.[53] The declaration opened a path towards a long process of the internationalization of the “Yugoslav Question” during the whole war and after it at the peace conferences in France. Subsequently, Serbia by this declaration tried to beat back a diplomatic pressure on herself by the Entente in regard to the requirement to make the territorial concessions to Bulgaria, Romania, and Italy for their participation in the war on the side of France, the UK, and Russia.[54]

Montenegro’s war aims

The proclamation of similar war aims was announced by Montenegro’s King Nikola I Petrović in which he called all Montenegrins to fight for the liberty of all Serbs and the Yugoslavs against Austria–Hungary, whose authorities proclaimed a war against both the entire Serbdom and the entire Slavdom. The Montenegrin Proclamation ends with a note that Serbia and Montenegro, in their “justifiable struggle”, would be supported by almighty Russia. Here is of the crucial importance to emphasize that Montenegro declared the war to Austria-Hungary immediately after Austria-Hungary did the same to Serbia in July 1914. Basically, Montenegro entered the war in 1914 only as a matter of the solidarity with the sister Serbia and scarifying in 1916 its own independence and freedom for the sake of supporting Serbia’s war aims. In other words, to help Serbia, that was the only war aim by the Kingdom of Montenegro in the Great War.

[1] The ethnic origin of Gavrilo Princip is to a certain extent problematic at least from the very fact that he is coming from the mixed Croat-Serb-Bosniak area of West Bosnia. Nevertheless, a surname Princip is of a Latin (Catholic) origin and never in history existed in Serbia.

[2] British historian Mark Cornwall published several talks by British and Belgian diplomats about F. Ferdinand’s warmongering policy in the Balkans [Mark Cornwall, Serbia, Keith Wilson (ed.), Decision for War 1914, New York: St. Martin Press, 1995, 55−96. Especially page 61].

[3] On the Kosovo Battle, see in [Rade Mihaljčić, The Battle of Kosovo in History and in Popular Tradition, Belgrade: BIGZ, 1989].

[4] Миле Бјелајац, 1914−2014: Зашто ревизија? Старе и нове контроверзе о узроцима Првог светског рата, Београд: Медија центар Одбрана, 2014, 27−45.

[5] Paul Robert Magocsi, Historical Atlas of Central Europe, Revised and Expanded Edition, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003, 121.

[6] Arūnas Gumuliauskas, Lietuvos istorija (1795−2009 m.). Studijų knyga, Šiauliai: K. J. Vasiliausko leidykla Lucilijus, 2010, 80.

[7] The headline of the Paper was: “How Russia and its Ruler Betrayed German Confidence, thus Causing a European War”.

[8] Mira Radojević, Ljubodrag Dimić, Serbia in the Great War 1914−1918. A Short History, Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga−Belgrade Forum for the World of Equals, 2014, 115.

[9] Such accusations were never proved being, therefore, a pure propaganda work by the Austro-Hungarian warmongers [Владимир Ћоровић, Односи између Србије и Аустро-Угарске у XX веку, Београд: Библиотека града Београда, 1992, 699].

[10] Quoted according to [Mira Radojević, Ljubodrag Dimić, Serbia in the Great War 1914−1918. A Short History, Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga−Belgrade Forum for the World of Equals, 2014, 116].

[11] Fritz Fischer, Germany’s Aims in the First World War, New York: Basic Books, 1967, see the map on page 107. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 3rd, 1918) was the first peace treaty signed during the WWI. It was concluded by illegal and not-legitimate anti-Russian Bolshevik government in occupied Moscow on one hand and Germany and Austria-Hungary on another. According to the treaty, “in return for peace on the Eastern Front, Russia lost Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, west Belorussia (Belarus), Poland, the Ukraine, and parts of the Caucasus. It thus lost almost half of its European territories, with around 75 per cent of its heavy industries. Russia was also obliged to pay 6 billion gold marks in reparations” [Jan Palmowski, A Dictionary of Contemporary World History from 1900 to the Present Day, Oxford−New York: 2004, 82].

[12] Peter J. Katzenstein (ed.), Mitteleuropa Between Europe and Germany, Providence−Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1997, 3.

[13] Rainer Eisfeld, “Mitteleuropa in Historical and Contemporary Perspective”, German Politics and Society, No. 28, 1993, 39.

[14] By academic definition, “Imperialism: refers to interlinked – political, social and economic – forces including nationalism and religion, which significantly shaped international relations from the early nineteenth century until after the Second World War” [Jeffrey Haynes et al, World Politics, New York: Routledge Taylor & Frances Group, 2011, 708].

[15] Alan Sked, The Decline & Fall of the Habsburg Empire 1815–1918, London−New York: Routledge Taylor & Frances Group, 1990, 259.

[16] About German imperial policy and geopolitical designs, see in [Henry Cord Meyer, Mitteleuropa in German Thought and Action 1815−1945, The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1955; Peter Stirk (ed.), Mitteleuropa: History and Prospects, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1994; Peter J. Katzenstein (ed.), Tamed Power: Germany in Europe, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997].

[17] Joachim Remak, “1914–The Third Balkan War. Origins Reconsidered”, The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 43, No. 3, 1971.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid. Also, according to Joachim Remark, “…the most basic decisions affecting peace or war were made by Berthold rather than Bethmann, and Pašić rather than Sazonov” [Ibid.].

[20] A. J. P. Taylor, The Habsburg Monarchy 1809−1918: A History of the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary, London: Penguin Books, 1990, 250.

[21] Joachim Remark, “1914–The Balkan War. Origins Reconsidered”, The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 43, No. 3, 1971.

[22] Živko Avramovski, Ratni ciljevi Bugarske i Centralne sile 1914–1918, Beograd: Institut za savremenu istoriju, 1985, 315.

[23] Haus-Hoff und Staatsarchiv, Viena, telegram No. 213.

[24] Živko Avramovski, Ratni ciljevi Bugarske i Centralne sile 1914–1918, Beograd: Institut za savremenu istoriju, 1985, 150–173.

[25] Ibid., see the map on page 225.

[26] Ibid., 170.

[27] Кнез Григорије Николајевич Трубецки, Рат на Балкану 1914–1917 и руска дипломатија, Београд: Просвета, 1994, 30.

[28] Ibid., 71−72.

[29] Ibid., 71–72; Archives of Serbia (Arhiv Srbije), Beograd, Ministarstvo inostranih dela (MID), Političko odeljenje, 1918, X-323, “Pašić to Vesnić”, January 18th, 1918; Dragoslav Janković, Bogdan Krizman, Građa o stvaranju jugoslovenske države, knjiga I, Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka, 1964, 45.

[30] Милорад Екмечић, Ратни циљеви Србије 1914–1918, Београд: Политика−БМГ, 1992, 8–9.

[31] “Spalajković-Ministry of Foreign Affairs” (Ministarstvo inostranih dela – MID), St. Petersburg, November 1/14th, 1914, Diplomatic Archives of Yugoslavia (Diplomatski arhiv Jugoslavije – DAJ), Beograd, secret, No. 10166.

[32] Милорад Екмечић, Ратни циљеви Србије 1914–1918, Београд: Политика−БМГ, 1992, 11.

[33] Никола Ђоновић, Црна Гора пре и после уједињења, Београд: Политика, 1939, 81; Branko Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988, Prva knjiga, Beograd: NOLIT, 1988, 23.

[34] The creation of a common Yugoslav state was proclaimed in Zagreb on November 23rd, 1918 and confirmed on December 1st, 1918 in Belgrade [Snežana Trifunovska (ed.), Yugoslavia Through Documents: From its Creation to its Dissolution, Dordrecht−Bosnot−London: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1994, 151−153, 157−160].

[35] About the war crimes of genocide committed by Austrian-Hungarian army in West Serbia in 1914, see in [Бранислав Станковић, Светланка, Милутиновић, Миодраг Гајић, Шабац и српска победа на Церу 1914, Шабац: Народни музеј Шабац, 2014].

[36] On this issue, see in [Vladislav B. Sotirović, Lingvistički model definisanja srpske nacije Vuka Stefanovića Karadžića i projekat Ilije Garašanina o stvaranju lingvistički određene države Srba, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2006].

[37] He was born on December 17th, 1888 in Cetinje – a capital of Montenegro at that time. His mother was a Duchess of Zorka – the oldest daughter of the Montenegrin Prince Nikola I [Бранислав Глигоријевић, Краљ Александар Карађорђевић, Књига прва: Уједињење српских земаља, Београд: БИГЗ, 1996, 24].

[38] About Serbian-Russian connections on the basis of the Russian pan-Slavic policy there are indisputable indications in: Международные отношениа в епоху империализма – Документы из архивов царского и временного правительства, 1878–1917 (ДЦА), Москва, 1935, V/55, “Letter by Aleksandar Karađorđević to Nikolai II”. After the Sarajevo assassination on June 28th, 1914, Austro-Hungarian Emperor/King Franz Joseph I clearly indicated in his letter to the German Emperor that Serbia is the principal pillar of the Russian pan-Slavic policy in the Balkans.

[39] Archives of Yugoslavia (Arhiv Jugoslavije), Beograd, Fond Vojislava Jovanovića, f. 119, “Projekat memoranduma za ruskog cara”, Salonika, February 3rd, 1912.

[40] Serbian consul in Odessa, Marko Cemović, proposed to Serbia’s Prime Minister Nikola Pašić to ask Russian authorities to send three divisions to the Balkans in order to help Serbian army to finally “realize Serbian national program” [Archives of Serbia, Beograd, Ministarstvo inostranih dela (MID), Političko Odeljenje, 1916, IX/415, “Cemović’s Memorandum to Pašić”]. In general, Tsarist Russia had been “the principal champion of Serbia among the Great Powers and, without the support of St. Petersburg, the Serbs were in urgent need of friends” [John B. Allcock, Explaining Yugoslavia, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000, 224].

[41] Archives of Military-Historical Institute (Arhiv Vojnoistorijskog instituta), Beograd, p. 2, k. 35, Operacijski dnevnik, “Naredba Komandanta I armije za 18. X 1912”.

[42] Бранислав Глигоријевић, Краљ Александар Карађорђевић, Књига прва: Уједињење српских земаља, Београд: БИГЗ, 1996, 364.

[43] Aleksandar I is called the “Unifier” after 1918 by Serbian historiography and his inter-war Yugoslavia was originally understood by Serbian historiographers and politicians (at least up to 1924) as a Greater Serbia [Владимир Ћоровић, Велика Србија, Београд: Култура, 1924]. However, the King of Montenegrin origin created in 1929 a Greater Montenegro within Yugoslavia under the name Banovina Zeta (one out of nine administrative units) but not a Greater Serbia. Further, on August 26th, 1939 it was created a Greater Croatia in Yugoslavia – a state within the state, under the name of Banovina Hrvatska (a separate administrative unit designed for ethnic Croats). Nevertheless, a separate Serbian administrative unit was never created in inter-war Yugoslavia. According to Croatian historiography, in Banovina Hrvatska, 19,1% of its inhabitants were ethnic Serbs (the 1931 census) [Dr. Stjepan Srkulj, Dr. Josip Lučić, Hrvatska povijest u dvadeset pet karata, Prošireno i dopunjeno izdanje, Zagreb: Hrvatski informativni centar, 1996, 101].

[44] Archives of SANU (Arhiv Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti), Beograd, The Memoires by General Panta Draškić, 14, 211; Милорад Екмечић, Ратни циљеви Србије 1914–1918, Београд: Политика−БМГ, 1992, 84.

[45] Ђорђе Ђ. Станковић, Никола Пашић и југословенско питање, Књига прва, Београд: БИГЗ, 1985, 148; Милорад Екмечић, Ратни циљеви Србије 1914–1918, Београд: Политика−БМГ, 1992, 87–89; Драгослав Јанковић, Србија и југословенско питање 1914–1915, Београд, 1973, 101; Драгослав Јанковић, “Нишка декларација”, Историја XX века: Зборник радова, бр. 10, Београд, 1969, 97.

[46] Ђорђе Ђ. Станковић, Никола Пашић и југословенско питање, Књига прва, Београд: БИГЗ, 1985, 150.

[47] Милорад Екмечић, Ратни циљеви Србије 1914–1918, Београд: Политика−БМГ, 1992, 177.

[48] Алекс Н. Драгнић, Србија, Никола Пашић и Југославија, Београд: Народна радикална странка, 1994, 124. According to the author, these territorial intentions were “everything but only not the intentions for the creation of a Greater Serbia”, Ibid., 124. It is interesting to present opinion by Seton-Watson that the future capital of Yugoslavia should be Sarajevo or to be shifted from one place to another [Милорад Екмечић, Ратни циљеви Србије 1914–1918, Београд: Политика−БМГ, 1992, 182]. Nevertheless, the idea that Sarajevo would be a capital of Yugoslavia was rejected by both dictators of Yugoslavia: King Aleksandar I Karađorđević and President Josip Broz Tito.

[49] At that time, South Serbia’s city of Niš was a temporal capital of the country.

[50]“Декларација владе Краљевине Србије о ратним циљевима Србије”, Српске новине, бр. 282, 7. децембар, 1914, Ниш.

[51] Ђорђе Ђ. Станковић, Никола Пашић и југословенско питање, Књига прва, Београд: БИГЗ, 1985, 154. According to Miodrag Zečević, Nikola Pašić and Aleksandar I Karađorđević favored the creation of Yugoslavia, while Serbia’s military establishment was against the union with the (Roman Catholic) Croats and Slovenes and, therefore, supporting the creation of a Greater Serbia [Миодраг Зечевић, Југославија 1918–1992: Јужнословенски државни сан и јава, Београд, 1994, 31–32].

[52] Ibid., 157; Ferdo Šišić, Dokumenti o postanku Kraljevine Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca (1914–1918), Zagreb, 1920, 10; A. Arnaoutovitch, De la Serbie la Yougoslavie: Notes et Documents, Paris, 1919, 2–3; Александар Белић, Србија и јужнословенско питање, Ниш, 1915, 83; Станоје Станојевић, Шта хоће Србија?, Ниш, 1915, 21–27.

[53] After Austrian-Hungarian armies attacked Serbia in the summer 1914 Serbia’s Government with the General-Staff of Serbia’s Army left Belgrade and moved to South Serbia’s city of Niš that was located nearby the border with Bulgaria.

[54] With regard to the problem of Italian territorial aspirations on the territory of East Adriatic littoral during the Great War, see in [Dragoljub R. Živojinović, America, Italy and the Birth of Yugoslavia (1917–1919), New York: Columbia University Press, 1972]. It is important to present a project created by the Croatian politician Dr. Ivan Lorković very soon after the break out of the war, who was at that time a leader of the Croatian part of the Croatian-Serbian parliamentary coalition in Zagreb. Namely, he sent to the Czech deputy in Prague – Prof. Masaryk – a Memorandum in which proposed the destruction of the Dual Monarchy and the formation of a single state of all Balkan South Slavs (including and the Bulgarians). However, this state was imagined as a federal union of sovereign states, like it was the Holy Roman Empire, in which every state would have its own assembly and a ruler. The crucial point of this proposal was to create with Serbia one single state but in which it would be fully preserved (alleged) continuity of Croatian (imagined) statehood [Franjo Tuđman, Hrvatska u monarhističkoj Jugoslaviji, Knjiga prva, Zagreb, 1993, 154–155].

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2018

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]