Views: 1509

Review: “The Chetniks” (1942), Treasury Star Parade Radio Play. Starring Orson Welles and Vincent Price.

Treasury Department War Savings Staff Radio Recording, Program 101, Treasury Star Parade “The Chetniks” Starring Orson Welles and Vincent Price and David Broekman and his Orchestra and Chorus, 1942. G-1897-P-1 (matrix). “E.T. announcements included.” William A. Bacher, director and producer. 1 pressed radio transcription sound disc: analog, 33 1/3 rpm, mono; 16 in. Recorded on one side only. “This program for sustaining use only.” Manufactured by the Allied Record Manufacturing Company, Hollywood, California.

“The Chetniks”

“The Chetniks” radio play was a poignant and powerful dramatization of the resistance movement in Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia led by Draza Mihailovich and the Chetnik guerrillas. The play starred Mercury Theatre veteran Orson Welles, then at the height of his fame after the success of Citizen Kane (1941), and actor Vincent Price, who had starred in The Return of the Invisible Man (1940), the sequel to the 1933 James Whale classic The Invisible Man. The play was written by Violet Atkins for the Treasury Star Parade radio program in 1942. V incent Price is the narrator, presenting the background to the events depicted in the play. Orson Welles plays Dushan, an ordinary Yugoslav who is swept up into the war after the German bombing and invasion of Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941. His wife Jovana is killed in the attack. Dushan then joins the Chetnik guerrillas led by Draza Mihailovich. Violet Atkin’s radio play is effective in focusing attention on the Chetnik resistance movement. The Chetnik guerrillas are relentless and undaunted.

incent Price is the narrator, presenting the background to the events depicted in the play. Orson Welles plays Dushan, an ordinary Yugoslav who is swept up into the war after the German bombing and invasion of Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941. His wife Jovana is killed in the attack. Dushan then joins the Chetnik guerrillas led by Draza Mihailovich. Violet Atkin’s radio play is effective in focusing attention on the Chetnik resistance movement. The Chetnik guerrillas are relentless and undaunted.

Orson Welles played the character of Dushan in an emotionally overwrought fashion that was suitable for radio. He delivered the lines in a faux Slavic or Serbian accent that was similar to his accent in playing the Russian character Gregory Arkadin in the 1955 film Mr. Arkadin. Welles played the role in an overstated and over-the-top style that relied on histrionics and on emotion or sentiment. His performance was effective and worked well in the context of a melodramatic radio play. The play was a perfect fit with the Treasury Star Parade format and formula. All the shows in the radio series were similarly overdramatized, patriotic, and emotion-laden. These shows were meant to move and to stimulate listeners. As a dramatic production for radio during wartime, “The Chetniks” is highly effective and succeeds. Vincent Price as the narrator and the supporting cast are also effective in maintaining the urgency and passion of the story. Price makes a heart-felt and passionate appeal at the end of the show to urge American citizens to buy war bonds and stamps in support of the war effort. The background music provided by David Broekman and His Orchestra and Chorus create urgency and foreboding and match perfectly the tone of the play and the performances.

Private versus Government Media

After the war, the Treasury Star Parade radio program and other programs sponsored by the U.S. government like it were criticized as government-sponsored media. They were dismissed as government propaganda. This criticism is facile and illusory, however, because it is based on faulty premises and assumptions. The first erroneous assumption made is that only the government seeks to persuade or promote an agenda. Ipso facto, any government sponsored program is propaganda or manipulation. This ignores the fact that non-governmental actors also persuade and manipulate. In wartime, the distinction between the government and private sector is also largely nominal and illusory. The boundary between the two becomes gray and indistinct. For all intents and purposes, there is no clear-cut dividing line between the two. The central concepts are persuasion and control.

Media manipulation is central in a democracy. The critics of wartime radio assume it is only the government that engages in propaganda. This reflects a fundamental misunderstanding and ignorance of how persuasion works in a democracy such as the U.S. The statement attributed to newspaper magnate and media czar William Randolph Hearst is crucial: “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.” This is what American public relations pioneer Edward Bernays said about media manipulation in a democracy in his seminal 1928 book Propaganda: “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society.” Thus, even in peacetime, there is an “invisible government” that controls and manipulates society.

Media manipulation is central in a democracy. The critics of wartime radio assume it is only the government that engages in propaganda. This reflects a fundamental misunderstanding and ignorance of how persuasion works in a democracy such as the U.S. The statement attributed to newspaper magnate and media czar William Randolph Hearst is crucial: “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.” This is what American public relations pioneer Edward Bernays said about media manipulation in a democracy in his seminal 1928 book Propaganda: “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society.” Thus, even in peacetime, there is an “invisible government” that controls and manipulates society.

Bernays was the nephew of Sigmund Freud. He also studied the theories of Ivan Pavlov and conditioned reflexes. He developed his PR techniques and theories also based on the work of Walter Lippmann. He worked with Lippmann on the Committee on Public Information during World War I, the U.S. propaganda office. He also wrote this in Propaganda (1928) as well: “If we understand the mechanism and motives of the group mind, it is now possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without them knowing it.” Governments, in other words, are not the only entities engaged in propaganda.

Edward Bernays, the “father of U.S. public relations”, also wrote that “the public mind” is constantly subjected to manipulation in a democracy in Propaganda (1928): “In almost every act of our lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons … who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.”

Not only was Bernays the father of U.S. PR techniques and mechanisms, but he was also very influential in the development of so-called Nazi propaganda. This is what Bernays wrote in his autobiography Biography of an Idea: Memoirs of Public Relations Counsel (1965) about the influence his writings had: “[Joseph] Goebbels … was using my book Crystallizing Public Opinion as a basis for his destructive campaign against the Jews of Germany. This shocked me.”

In both peacetime and in wartime, we are persuaded and manipulated. The lines blur, however, between the private and government sectors in wartime.

Orson Welles

Orson Welles’ career in radio is legendary. Between 1936 and 1941 alone, he appeared in over a hundred radio drama productions as a writer, actor and director. He created the Mercury Theatre on the Air with John Houseman which dramatized major works such as Heart of Darkness, Dracula, A Tale of Two Cities, and Hamlet. Welles was Lamont Cranston as The Shadow in 1937 and 1938. He is most famous for his dramatization of H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds on October 30, 1938 which caused a nation-wide panic in the U.S. In the 1950s he starred in a BBC radio series, The Lives of Harry Lime, based on The Third Man (1949). Orson Welles was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 1988.

In 1962, he made The Trial in Zagreb, Yugoslavia based on Franz Kafka’s novel. While making the movie, he established a relationship with Croatian actress Oja Kodar. Welles continued to work in Communist Yugoslavia, where he filmed The Deep from 1966 to 1969.

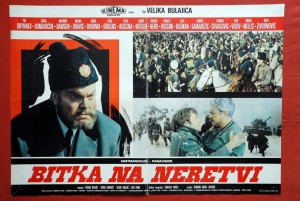

Orson Welles as a Chetnik Senator on a 1969 Yugoslav movie poster for the film Bitka na Neretvi, The Battle of Neretva, directed and co-written by Veljko Bulajic, Bosna Film, Kinema Sarajevo.

In an ironic twist, Welles would again play a Chetnik guerrilla, but this time as a villain in a negative portrayal, in a Yugoslav Communist government propaganda epic in 1969. He played a Chetnik Senator in Tito’s Communist propaganda epic film The Battle of Neretva, or Bitka na Neretvi (1969). Yul Brynner, portrayed a Communist Partisan leader in the film. This movie had a massive budget that was personally approved by Yugoslav Communist dictator Josip Broz Tito. The film budget was estimated at $71,015,000. It took 16 months to complete the star-studded propaganda film. It was the first of the Yugoslav World War II Communist film productions that were sponsored by the Yugoslav Government. Funds were provided by fifty-eight Yugoslav state companies. This Communist propaganda epic is the most expensive Yugoslav movie ever made and at the time of its production was the most expensive film ever made in Eastern Europe outside of the Soviet Union. 175 minutes in length, the movie was released on October 7, 1969. It was overdubbed in 1971 for an international audience.

This movie was a total falsification and fabrication of history. Operation Weiss was launched by the German occupation troops against both the Chetnik guerrillas under Draza Mihailovich and the Communist Partisans under Josip Broz Tito. The German objective was to clear out the guerrillas in anticipation of an Allied landing on the Adriatic Coast. Ironically, it was following this offensive in March, 1943 that Tito and the Communist Partisans collaborated with the Nazis in Bosnia. In order to concentrate his forces on destroying Mihailovich’s Chetniks, Tito negotiated a deal with German commanders to collaborate against the Chetniks. Adolf Hitler, however, would not approve the deal. Moreover, the Partisans nearly escaped being totally wiped out by German forces. This defeat was turned into a military victory by Communist Partisan propaganda. Typically, Communist propagandists could transform white into black, defeat into victory, collaboration into resistance.

Welles continued to work with Croatian filmmaker Oja Kodar, who made the 1993 Croatian film Vrijeme Za… (A Time For…). Welles also worked closely with Serbian-American film director Peter Bogdanovich (Targets, The Last Picture Show, What’s Up Doc?) who wrote two books on his film career, The Cinema of Orson Welles (1962) and This is Orson Welles (1992). Welles also played J.P. Morgan in the biopic Tajna Nikole Tesle, The Secret of Nikola Tesla (1980) with Oja Kodar, who played Catherine Johnson. The movie was made in Zagreb, Yugoslavia by the Kinematografi production company.

Orson Welles created a critical and popular sensation with his first feature film, Citizen Kane (1941), which was nominated for 9 Academy Awards and is universally regarded as the greatest motion picture ever made. Welles won an Academy Award with Herman Mankiewicz for Best Writing (Original Screenplay). His major films included The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) for RKO, The Lady from Shanghai (1947), Macbeth (1948), The Third Man (1949), Othello (1952), Mr. Arkadin (1955), Touch of Evil (1958), The Trial (1962), Chimes At Midnight (1965), A Man For All Seasons (1966), and The Voyage of the Damned (1976).

Vincent Price

Vincent Price, like Welles, had a long and extensive career on the radio. He appeared in the radio programs Bob and Ray, Lux Radio Theater, Hollywood Star Playhouse, Philip Morris Playhouse, Screen Guild Theater, and Suspense. He was also Simon Templar in the detective radio series, The Saint, from 1944 to 1951 on NBC Radio. In 1973, he was the host of the BBC radio series The Price of Fear. He made audio recordings for Caedmon which such as Poetry of Shelley which included “Adonais”, “Ode to the West Wind”, and “Ozymandias” and recordings of Edgar Allan Poe short stories, including “The Gold Bug”, Ligeia”, “Morella”, “Berniece”, and “The Imp of the Perverse”. His major movies included The Invisible Man Returns (1940), The Song of Bernadette (1943), The House of Wax (1953), The Ten Commandments (1956), The Fly (1958), The Return of the Fly (1959), The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), The Last Man on Earth (1964), The Masque of the Red Death (1964), The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971), and Edward Scissorhands (1990).

Violet Atkins

Violet Atkins Klein wrote for radio, television, and for films. She began her career in New York but moved to Los Angeles in the late 1940s. She wrote for radio in the 1940s, writing scripts for Camel Caravan (“Afternoon Wedding”, “Sunday Morning in Our Town”) and The Camel Hour (“I Saw a Parade Today”, “Tonight… “), and for television in the 1950s, writing scripts for the TV shows Code 3, Waterfront, and You Are There. For the Treasury Star Parade radio series, she wrote “All God’s Children”, “Balcony Empire”, “The Bell of Tarchova”, “Education for Victory”, “I Saw the Lights Go Out in Europe”, “I Speak for the Women of America”, “Lyudmila Pavlichenko Leaves a Letter to the Future”, “The Murder of Lidice”, “No Victory without Sacrifice”, “Shostakovich”, “Sound of an American”, “There’s a Nation”, and “V for Victory”.

Treasury Star Parade

Broadcast on 833 radio stations across the U.S. in 1942 and 1943, the Treasury Star Parade radio series was highly successful and was critically acclaimed. The purpose of the show was to promote the sale of war bonds and stamps.

Before the advent of television in the 1950s, radio was one of the dominant forms of media in the United States. Almost 80% of all American homes had at least one radio in the 1940s. Along with newspapers and newsreels, radio was how Americans followed the news. Radio was much more instantaneous, direct, and personal. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt became known for his fireside chats over the radio. The radio was in the 1940s what television would become in the 1950s and subsequently thereafter in American society and culture.

The U.S. Treasury Department sponsored and produced the Treasury Star Parade program, which was recorded in Hollywood and New York and syndicated to radio stations nationwide. The program debuted on April 11, 1942. William A. Bacher was the producer. Larry Elliot and Paul Douglas were the announcers.

Media accounts of the program showed that it was an immediate and smash hit. In the New York Times article “759 Stations, And Going Strong; Stars on ‘Parade,’ by Transcription, for The Treasury”, April 5, 1942, Edward Jenks explained that the show was produced to urge and to motivate Americans to “Buy a Share in America”:

“In Treasury Star Parade, newest series of transcribed programs under Treasury Department sponsorship, director William Murray and producer William A. Bacher are offering listeners entertainment by some of the best talent of the country and through it are giving new meaning and urgency to the slogan ‘Buy a Share in America’.”

In “The ‘Parade’ Goes On; Being a Salute to the Treasury’s Fifteen-Minute Recorded and Star-Studded Shows, Now Heard on 833 Stations”, the New York Times, November 22, 1942, John K. Hutchens noted that the radio series was meant to sell war bonds and stamps:

“The more you listen to and think about them the more you are inclined to believe that the Treasury Star Parade shows are, in their way, just about the best of all those domestic wartime programs whose task it is to awaken, convince, entertain — and, not incidentally, to sell war bonds and stamps.”

In “War Bond Sales Goal Looms; Early Results Under Treasury’s Voluntary Plan Appear to End Compulsory Proposals” in the New York Times, June 21, 1942, Section Review of the Week Editorials, Page E6, John MacCormac reported that 800 out of 868 stations were then running the show:

“Almost 60 per cent of the radio stations throughout the country have installed payroll savings plans and some 800 stations out of 868 are now broadcasting the “Treasury Star Parade” series of programs three times weekly. Newspapers have carried front page editorials, photographs.”

In “Wanted: Script Writers — This Week’s New Shows — Other Items From Radio Row”, New York Times, June 14, 1942, the announcement was made that script writers for the series were sought:

“The Treasury Star Parade, whose fifteen-minute recorded shows have been among the better war programs, advises that it is facing a shortage of scripts — this despite the generosity of sundry well-known authors who have contributed their services . . . . Scheduled for Treasury Star Parade release this week are Norman Rosten’s ‘Ballad of Bataan,’ starring Alfred Lunt, and ‘I Saw the Lights Go Out in Europe’.”

The show was so popular that over 90% of American radio stations carried the program. In “One Thing and Another”, New York Times, August 9, 1942, it was reported that 828 stations were carrying the series at that time:

“Charles Gilchrist, chief of the radio section of the War Savings Staff, of Washington, was in town last week and reported that 828 out of a possible 868 stations were now carrying the Treasury Star Parade, a figure which has all the earmarks of a record.”

Even First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt made recordings for the Treasury Star Parade program to promote her book This Is America. She appeared on the April 29, 1943 program, #169, “This Is America”. She introduced dramatizations from the book, which she co-authored with Frances Cook MacGregor, featuring Fredric March.

Not only were actors and playwrights recruited for the war effort, but songwriters and composers were as well. In God Bless America: Tin Pan Alley Goes to War, Kathleen E.R. Smith detailed how the government sought to sponsor songwriters to write songs that would support the war effort and boost morale. Such songs as “Goodbye, Mama. I’m Off to Yokohama,” “There Are No Wings on a Foxhole,” and “The Sun Will Soon be Setting on the Land of the Rising Sun” were written to support the war effort. She found that this effort was unnecessary because morale remained high during the war.

She examined how the U.S. government sponsored radio shows such as Treasury Star Parade to support the war effort:

“Prior to February 1,1943, the OWI sent complete pre-recorded programs to radio stations for broadcast once or twice a week; shows included Treasury Star Parade , by the Treasury Department; Victory Front, Victory Volunteers, and This Is Our Enemy, by the OWI; and Voice of the Army, by the US Army. Other distributed programs, based on ‘timely and topical’ war information, appeared only once. With the exception of Treasury Star Parade, the OWI discontinued after February 1 all of its pre-recorded shows. … From Feb 1 1943 the OWI sponsored a new program Uncle Sam.”

Government Propaganda

The Radio Star Parade program was criticized after the war, however, because of U.S. government involvement in producing and sponsoring the radio program. In Television and the Red Menace: The Video Road to Viet Nam (2nd ed., Praeger, 2005), J. Fred MacDonald analyzed the radio show in the chapter “The Emergence of Politicized Television”, arguing that the program was “propaganda” meant to sell the war to Americans:

“Government propagandists also used commercial radio to convince listeners that the United States was right in fighting World War II. The sting of Pearl Harbor did not ensure a lengthy popular commitment to wage a two front war. The patriotism evidenced on regular network programming was also insufficient to ensure acceptance of the protracted war. Instead, the federal government became a producer of propagandistic shows whose intent was to keep domestic morale committed to the national war policies.”

Treasury Star Parade was not unique. There were dozens of programs tasked with the same mission and objective. Music for Millions was another radio show produced by the U.S. Treasury Department which featured well-known musicians and vocalists to help raise funds for war bonds. The Army Hour was another which featured music and drama programs that were intended to stir the emotions of American listeners. Soldiers with Wings featured music, comedy, guest celebrities, a GI audience, and a positive image of the Army Air Corps sponsored by the Mutual network which was broadcast from military bases and installations. Glenn Miller had a similar radio program which he hosted entitled I Sustain the Wings which ran from 1943 to 1944 under his direction featuring music and dramatizations that promoted enlistment into the U.S. armed forces.

Treasury Star Parade was regarded, however, as the most flagrant government-sponsored radio program of the war:

“The most flamboyant of government propaganda pieces, however, was Treasury Star Parade. This program consisted of more than 300 quarter-hour shows produced for the Treasury Department and heard in 1942 and 1943 on more than 90 percent of American radio stations. In the hyperbolic rhetoric of propaganda, this show sold War Bonds and American involvement in World War II. The programs were recorded in Hollywood and distributed free to all stations willing to air them—whenever and as often as the recipient station desired.

“This was radio in the service of government. Treasury Star Parade manipulated traditional social values, appealed for domestic unity, painted the enemy as demonic and the Allies as noble. It also intimidated listeners into buying War Bonds and supporting the war—all within a format that was well produced and highly entertaining. Typically, in one dramatic vignette, “The Second Battle of Brooklyn,” listeners were told that they, the noble common people, were indispensable, because this was a “little guys’ war.” As one character explained it, “Hitler ain’t fightin’ kings and queens, no more. We’re the only ones who can win it… the little people, all dressed up in our haloes and gas masks.”

These criticisms are largely disingenuous and off the mark. In wartime, the role of the government is to mobilize the population and to gain their support. Morale is crucial. Obtaining funding for the war is vital. To expect otherwise is illogical and irrational and not conducive to winning the war.

The methods and techniques of the program were criticized in particular:

“Treasury Star Parade was wartime government propaganda. Deep-voiced announcers projected the horrors of Nazi-occupied Chicago, and they spoke of the savagery of the Japanese attack upon Hong Kong. Nazis were associated with arrogance, the enslavement of women and children, and the barbarization of European culture. The Japanese were mentioned in racially disparaging terms that depicted them as monkey-like and subhuman. Consider the words spoken by Fredric March in a program called A Lesson in Japanese:

“Have you ever watched a well-trained monkey at a zoo? Have you seen how carefully he imitates his trainer? The monkey goes through so many human movements so well that he actually seems to be human. But under his fur, he’s still a savage little beast. Now, consider the imitative little Japanese who for seventy-five years has built himself up into something so closely resembling a civilized human being that he actually believes he is just that.

“These were emotional times. In many ways the Second World War threatened the American republic. But the war had begun in 1939 without the United States. For two years, while the official policy in Washington was neutrality, the brutal Nazis and Japanese had slaughtered British, French, Chinese, Dutch, Polish, Russian, and other peoples. Yet, until the Americans joined the battle, commercial radio reported, but did not dramatize, the inhumanity of the German and Japanese conquests. Thus, rather than an accurate picture of Axis militarism that transcended government policy and public opinion to report the truth, accuracy seemingly had to wait until the United States entered the war. Then, it was rhetorically distorted, charged with emotion, and turned into propaganda supportive of the new government policy.”

In a time of war, however, which is an emergency or crisis period, the preservation of the country is paramount. The President and the Congress could sponsor and enact legislation which could control the media or greatly curtail its role. Under Article 606 of the Communications Act of 1934, moreover, the U.S. President had the power to confiscate all broadcasting facilities in time of national crisis. In wartime then, the media was not independent but existed so long as it furthered national or government objectives and goals. The distinction between government and private media, thus, drastically changes in time of war.

The Treasury Star Parade. Edited by William A. Bacher. New York: Farrar, 1942. “27 radio plays by Stephen Vincent Benet, Thomas Wolfe, Paul Gallico, Thomas Mann, John Latouche, Arch Oboler, Norman Rosten, Violet Atkins, and other distinguished authors as produced and directed by William A. Bacher with an Introduction by Henry Morgenthau, Jr. History is a Branding Iron!”

False Dichotomy

This whole analysis and critique of wartime radio in the U.S. during World War II, however, is based on faulty or questionable assumptions. He assumes that merely because the U.S. government sponsored the radio program, it constitutes propaganda and control of the airwaves. But what he neglects is the fact that private broadcasts could, and in most cases were, much more racist, jingoistic, and propagandistic than so-called government-sponsored programs. This is the key point in understanding this issue. He makes a faulty assumption and creates a false dichotomy.

The assumption is that you can make a distinction during wartime between government and private sector persuasion. World War II was a total war. In Europe and in the United States. In total war, the lines between the private and the government sector blur. As embedded journalists have shown during the Iraq War of 2003, there is no distinction made between private and government sectors in wartime. The distinction is illusory. Everyone is 100% behind the war effort. Everyone is a soldier. In wartime, the distinctions, if there are any, are far less meaningful. To not realize this is to oversimplify the issue to the point of absurdity.

The assumption is that you can make a distinction during wartime between government and private sector persuasion. World War II was a total war. In Europe and in the United States. In total war, the lines between the private and the government sector blur. As embedded journalists have shown during the Iraq War of 2003, there is no distinction made between private and government sectors in wartime. The distinction is illusory. Everyone is 100% behind the war effort. Everyone is a soldier. In wartime, the distinctions, if there are any, are far less meaningful. To not realize this is to oversimplify the issue to the point of absurdity.

Moreover, critics neglect the dangers of self-censorship and advocacy media or journalism. As we witnessed during the 1992-1995 Bosnian civil war and the Kosovo War in 1999, the private or commercial media can, in many instances, be a much greater danger than government media. Like Hearst, the private or commercial media has an economic or financial interest to “manufacture” a war in the manner of Hearst in the run up to the 1898 Spanish-American War. Private media can be jingoistic and militantly aggressive to a point that exceeds government media. The private media need not be as concerned with international laws and covenants or diplomacy based on the relations between nations. For the private journalists, the sky is the limit. They can manufacture and fabricate events and engage in persuasion and manipulation that is a greater threat than so-called government-run media. The only criterion would be financial gain. And in such run amok cases as in Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan, is there a meaningful distinction between government and private media at all?

Embedded journalists did not emerge for the first time in 2003 in the Iraq War. The concept originated during World War II. Robert Livingston Denig, Sr., a decorated Marine Corps veteran, organized the Division of Public Relations during World War II. Denig is credited with introducing the concept of embedding combat correspondents or reporters into the American armed forces to cover the war. For his work as director of the Division of Public Relations, he was awarded the Legion of Merit.

During World War II, U.S. news reporting was controlled by the govenment. The Office of War Information (OWI) screened all news reports on the war and could suppress material that was deemed a danger to “domestic unity”. On January 15, 1942, the “Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press” was released which explicitly defined how news on the war was to be reported. An Office of Censorship was also created by the government. The government relied on self-censorship and the voluntary acceptance of the code requirements. Every major news service in the U.S. adopted the regulations. The 1,600 members of the press who were accredited by the military also accepted the code.

Novelist John Steinbeck, who was a reporter during the war, recalled how all correspondents became part of the war effort and manipulated the facts: “We were all a part of the War Effort. … [T]he truth about anything was automatically secret … By this I don’t mean that the correspondents were liars … [I]t is in the things not mentioned that the untruth lies.” Control and conformity were achieved through government regulations and through voluntary, self-imposed restraints. All media in the U.S. was thus government controlled. There was no private media to speak of. The dichotomy between a private and government media thus is a spurious and dubious one.

In a speech in 1950 at the FBI National Academy, Niles Trammell, chairman of the board of NBC, explained the symbiotic relationship between commercial broadcasting and the war effort of the government:

“Radio in the United States shouldered arms and, together with the American people and American industry, geared itself for total war. Throughout the long years until victory was won, it carried the responsibility of broadcasting for the United States government. The story of its contribution is too large ever to be recorded in its entirety. Every wartime effort found its support in radio …. in every area of the war effort … American radio proved itself a mighty weapon in the nation’s service….”

Conclusion

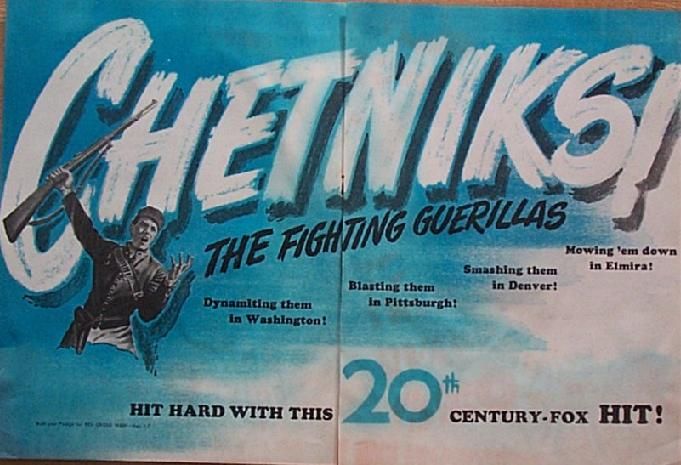

“The Chetniks” is a poignant and at times overwrought presentation that dramatizes the Yugoslav Chetnik resistance during World War II in concise and succinct terms. The radio play is not unlike the American World War II films Casablanca, Mrs. Miniver, or Chetniks! The Fighting Guerrillas, all produced in 1942.

The program demonstrated that Draza Mihailovich and the Chetnik guerrillas were allies of the United States, the UK, and the USSR during World War II. The program highlighted the chimerical nature between commercial and government media. In wartime, there is no meaningful distinction between government and private media. Whatever distinction exists is negligible. Both work together in a symbiotic relationship to achieve a result, military victory in the conflict.

Bibliography

Bacher, William A., ed. The Treasury Star Parade. New York: Farrar, 1942.

Horten, Gerd. Radio Goes to War: The Cultural Politics of Propaganda during World War II. University of California Press, 2002.

Lessner, Erwin Christian. “The Fight of the Chetniks.” Reader’s Digest, June, 1942, Vol. 40, No. 242, pp. 37-40.

“Fight of the Chetniks-The Lost Gold Piece”, Radio Reader’s Digest, Episode 3, September 27, 1942.

MacDonald, Fred. “Government Propaganda in Commercial Radio: The Case of Treasury Star Parade, 1942-1943.” The Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 12, Issue 2, pp. 285–304, Fall, 1978.

MacDonald, J. Fred. Television and the Red Menace: The Video Road to Viet Nam. 2nd ed. Chapter: “The Emergence of Politicized Television”. Praeger, 1985.

Smith, Kathleen E.R. God Bless America: Tin Pan Alley Goes to War. Lexington, KYKentucky, 2003.

Originally published on 2012-08-24

Author: Carl K. Savich

Source: Serbianna

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.