Views: 1549

Four men, accused of being partisans, are alleged to have been buried alive. The wife of a partisan is said to have been “pierced by bayonets and drowned in a garbage pit” [искололи тело штыками и утопили в помойной яме].

The author (who is unnamed) states that his own elderly father was taken as a hostage by Allied forces from the town of Kharitonovka [Харитоновка]. He was returned home alive but in a bloodied condition. He is said to have died a few days later, after asking “Why did they torture me…”? [За что меня замучили]. The man is said to have left five orphans behind.

It further describes young men … who were “tortured for days, had their teeth knocked out and their tongues cut off.”

Strolling the cavernous and well-appointed halls of Russia’s carefully renovated Central Naval Museum [Центральный Военно-морской Музей] near the Neva River in St. Petersburg, one can find an assortment of interesting artifacts, not least the small skiff in which Peter the Great learned to sail more than three centuries ago now.

Strolling the cavernous and well-appointed halls of Russia’s carefully renovated Central Naval Museum [Центральный Военно-морской Музей] near the Neva River in St. Petersburg, one can find an assortment of interesting artifacts, not least the small skiff in which Peter the Great learned to sail more than three centuries ago now.

Among the many captured battle standards from Sweden, Turkey and Germany that are proudly displayed, a few of the expansive oil paintings took me by surprise.

There was, for example, a picture depicting the Russian fleet at anchor off of Kodiak in Alaska during the mid-eighteenth century. Another showed the Soviet Navy’s first submarine kill by torpedo on July 31, 1919. On that day, the British destroyer HMS Vittoria was sunk by the Bolshevik submarine Pantera under the command of Alexander Bakhtin. I had known, of course, that Allied forces intervened in the Russian Civil War during 1918–22, but was not aware that the intervention had occasioned such deadly incidents.

I was starkly reminded of this fact again during a December 2017 visit to Vladivostok, when quite by chance I came upon a full page article in the December 5 issue of the local newspaper The Competitor [Конкурент] under the following headline: “Atrocities of the American Invaders in Primorye” [Зверства Американских Захватчиков в Приморье]. A close reading of the reasonably detailed Russian-language article (which seems to have been republished) suggests that the allegations are serious.

In keeping with the mission of this Bear Cave series of columns to try to gain insights into the Russian mind-set or weltanschauung, we will take a close look at this article. It not only reveals a plethora of history long forgotten in the United States, but is also suggestive of the new and dangerous Cold War climate that is quickly overtaking U.S.-Russian relations that only a decade ago could be considered friendly or at least pragmatic. However, a careful study of Russian history and U.S.-Russian relations, in particular, could help to defuse this most dangerous rivalry even as the conventional media (in both countries it seems) daily stirs the boiling cauldron of rivalry.

What were more than 7,000 “doughboys” doing in Siberia at the end of the First World War? To make a long and complex story—explored in detail by such luminaries as George Kennan—a bit shorter, the intervention by a large group of allied powers was not simply anti-Bolshevik, but was premised at the outset as a wartime operation to prevent Germany from gaining access to Russia’s resources and especially Allied supplies and material. That explains the focus on large ports, including both Murmansk and Vladivostok.

An additional bizarre wrinkle in this tale is the subplot of a large group of Czech soldiers, seemingly trapped in the Russian Civil War, and trying to “escape” to the east in order to rejoin the fight with the Allies. But as an impressively detailed English-language account of the U.S. mission in the Russian Far East records, these operations extended well beyond Vladivostok, reaching Khabarovsk for example, and U.S. forces engaged in quite extensive combat. On the bloodiest day, June 25, 1919, twenty-five American soldiers were killed when “partisan units” attacked their encampment near the village of Romanovka about twenty miles northeast of Vladivostok.

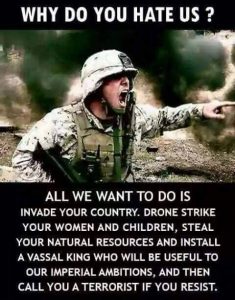

Our interest here, however, is the Russian perception of these events and how they resonate today. Hinting at a rather anti-American disposition, the author asks at the outset: “… where have the Americans not stuck their nose, leaving behind a not so fond memory of themselves”? [куда они свой нос не совали, оставив недобрую память о себе] Then, it is further lamented that “… the majority of our youth today, educated by American action films and nurtured by hamburgers and Coca-cola do not even have a small bit of understanding [of this history].” According to the author, all the evidence is available in local papers and in the archives.

Many examples of atrocities are given. Four men, accused of being partisans, are alleged to have been buried alive. The wife of a partisan is said to have been “pierced by bayonets and drowned in a garbage pit” [искололи тело штыками и утопили в помойной яме]. The author (who is unnamed) states that his own elderly father was taken as a hostage by Allied forces from the town of Kharitonovka [Харитоновка]. He was returned home alive but in a bloodied condition. He is said to have died a few days later, after asking “Why did they torture me…”? [За что меня замучили]. The man is said to have left five orphans behind. It further describes young men from Vladivostok that were accused of being partisans, who were “tortured for days, had their teeth knocked out and their tongues cut off.”

The author acknowledges that the Americans were not alone in allegedly committing such atrocities, suggesting that the Japanese were hardly inferior in this respect. Two towns are said to have been destroyed by Japanese soldiers in January and February 1919. Citing a Japanese reporter, many inhabitants were burned in their homes when the villages were “completely torched.” [были полностью сожжены]. In addition to local papers, the author explains that pictures of these atrocities can be found in the archives of museums in Vladivostok. It is lamented that, “It is true that politicians today do not want to remember [these events] (and many of them, alas, do not even know about this).”

I am not a historian and the point here is not to dig up old wounds from a century ago. Moreover, I should note that the Russians I met in Vladivostok could not have been more friendly and welcoming to our American delegation. That made the article all the more jarring after reading it. Whether there is some validity to these accusation or this is instead just warmed over Soviet propaganda is not clear. Given the inherent difficulties of counterinsurgency, the lack of oversight (the “CNN effect”) in those times, and the other atrocities that are known to have occurred in the Asia-Pacific, specifically in the Philippines just a few years before, these accounts cannot be dismissed altogether. In fact, watching the Iraq and Afghanistan interventions unfold, one is tempted to conclude that the Washington foreign policy establishment has learned little over the past century.

But these stories also serve Moscow’s nationalist and propagandistic agenda, as well of course. Russia may indeed have as many Ameriphobes [Aмерoфобы] by now as our country counts Russophobes. If one reads the Washington Post and the New York Timesregularly, one is familiar with the concept that great power rivalry sells newspapers, of course. Even the editorial teams at those rabidly Russophobic newspapers would have to concede that allegedly stolen e-mails or purchased facebook advertisements are in a rather different category than allegations of torture and murder of civilians, even if those incidents occurred some time ago.

Yet there is more “obscure” history in U.S.-Russian relations that is actually much more pertinent to the strategic quandaries that confront us today. During 1854–56, a quarter million Russians died fighting against the combined forces of France, Britain and Turkey in order to hold Crimea in the Russian Empire. That was Russia’s first Gettysburg-like bloodletting on Crimea. Count Lev Tolstoy, as many readers will know, was in Sevastopol then to record the slaughter. The second “Gettysburg moment” for Russians on Crimea came during the Second World War, when the determination of the Soviet defenders of the Sevastopol fortress forced the Nazis to commit major forces that were then significantly battered just before the decisive battle at Stalingrad. Had the Red Army not held out to the tragic end, Hitler might have been victorious in WWII.

Yet there is more “obscure” history in U.S.-Russian relations that is actually much more pertinent to the strategic quandaries that confront us today. During 1854–56, a quarter million Russians died fighting against the combined forces of France, Britain and Turkey in order to hold Crimea in the Russian Empire. That was Russia’s first Gettysburg-like bloodletting on Crimea. Count Lev Tolstoy, as many readers will know, was in Sevastopol then to record the slaughter. The second “Gettysburg moment” for Russians on Crimea came during the Second World War, when the determination of the Soviet defenders of the Sevastopol fortress forced the Nazis to commit major forces that were then significantly battered just before the decisive battle at Stalingrad. Had the Red Army not held out to the tragic end, Hitler might have been victorious in WWII.

But let us return to that scenic, but blood-soaked piece of real estate, jutting prominently out into the Black Sea known as Crimea, which has seemingly tipped European security on its head during the last three years. For all the extensive punditry explaining how Russia’s absorption of Crimea upset the “rule-based order,” there has been hardly a reflective thought regarding the Crimean War and its significance. After all, that grisly conflict, which spawnedthe poetic legend of the Charge of the Light Brigade and figures such as Florence Nightingale, was essentially fought by London and Paris for the same purpose ostensibly that NATO has had for the last several decades: namely containing alleged “Russian aggression.”

In his brilliant 2010 book on the Crimean War, author Orlando Figes explains the evolution of strategy in London during the decades prior to that unfortunate war: “… the phantom threat of Russia entered into the political discourse of Britain as a reality. The idea that Russia had a plan for the domination of the Near East and potentially the conquest of the British Empire began to appear with regularity in pamphlets, which in turn were later cited as objective evidence by Russophobic propagandists in the 1830s and 1840s.” Hmm … sounds eerily familiar.

However, it is most interesting to consider how Americans of that era looked upon Russia’s epic struggle against Britain and France for control of Crimea. Figes’ explanation is worth quoting at length:

US public opinion was generally pro-Russian during the Crimean War … There was a general sympathy for the Russians as an underdog fighting against England, the old imperial enemy, as well as a fear that if Britain won the war against Russia it would be more inclined to meddle once again in the affairs of the United States. … Commercial contracts were signed between the Russians and the Americans. A US military delegation (including George B. McClellan …) went to Russia to advise the army. American citizens sent arms and munitions to Russia … American volunteers went to Crimea to fight or serve as engineers on the Russian side. Forty US doctors were attached to the medical department of the Russian Army.

The above American inclination to take Russia’s ownership of Crimea rather seriously “way back when,” points to the peculiarity that exists today of basing U.S. strategy in Eurasia (and other parts of the world) on contesting Russia’s claim to that blood-soaked peninsula in the Black Sea. Never mind that everyone knows that the Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in 1954 gave over Crimea to the Ukraine SSR as a rather meaningless gesture with obviously unintended consequences. It might further be recalled that Russia first acquired Crimea in the same year, 1783, that marked the end of the American Revolution.

Originally published on 2018-01-27

Author: Lyle J. Goldstein

Source: Russia Insider

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.