Views: 1360

The origins of Czechoslovakia (1918−1920)

Czechoslovakia gained its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918. Even though the Austrian-Hungarian Empire was one political entity, the Austrian part and the Hungarian part existed under a Dual Monarchy. Each half of the empire had a large amount of control over their area independent of the other half of the country. The differing policies of the Austrians and the Hungarians had a strong impact on the state of what is now the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. In particular, the Czech industry was developed, while Slovakia remained a mostly agrarian area managed by a Hungarian elite. This led to two main differences between the Czech and the Slovak side of the country that would affect the policies of the Government:

- One was that Slovaks had a much less developed civil society compared to the Czechs since they were unable to develop one while being part of Hungary.

- Secondly, Slovakia remained a mostly agrarian society, in part due to its position as the breadbasket for the Austro-Hungarian Empire but also because of the lack of money that was invested in the area.

Slovakia’s history on the borderlands between the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire affected its development. Slovakia was unlike areas of the Czech Republic which had been able to develop industry not only due to their resources but due to their location away from war actions and closer to the major European cities, and their central location within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Slovakia had been developed in the history of the Kingdom of Hungary as a barrier against the advancing Ottoman Empire toward Central Europe. After the Ottoman Empire was no longer a danger due to its severely weakened state and had lost lands in the Balkan peninsula, money was invested elsewhere in the Habsburg Monarchy. While the western part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was developed economically, Slovakia remained predominantly an agricultural society. Unlike Slovakia, the Kingdom of Bohemia (later the Czech Republic) had at one time existed as an independent (till 1526) and the autonomous country as recently as the early seventeenth century (till 1620). It became part of the new Austrian Empire in 1804, and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1867 until Czechoslovakia became proclaimed as an independent state in 1918.

The development and spread of nationalism in Europe during the mid-19th century led indirectly to the development of a Slovak national identity. This was in part due to the fears of Magyarization which were felt by all minorities within the Hungarian part of the Austrian Empire and later since 1867 a Dual Monarchy. In 1848, the governing body of Hungary issued the so-called “April Laws” which essentially established Hungary as an autonomous area within the Austrian Empire, which the central Government of the Austrian Empire was unable to address due to the numerous nationalistic movements that were spreading through its empire. The Hungarian Government then used these policies to strengthen Hungarian identity by the engaged policy of Magyarization. This had numerous effects on many different aspects of life, for example, the use of Hungarian language in education. However, the development of a Slovak national identity did not begin in earnest until Czechoslovakia became a country, and resistance was felt towards a Czechoslovak identity, which Slovaks felt was the promotion of a Czech identity at the expense of the Slovak one.

Czechoslovakia gained its independence in a series of steps. Even before the creation of the common state, the idea of Czechoslovakia was advocated by Czechs and Slovaks living abroad (in the USA). This idea was also supported by the eventual winners of WWI for various geopolitical and other reasons:

- One of the reasons for this support was the idea that multinational empires have to be replaced by the national states.

- Monarchies have to be replaced by democratic Governments of the republics.

- Countries had to justify their legitimacy to the rest of the world and one way of doing this was by stating a certain ethnic group’s claim to an area due to their historic presence in that land.

- Another reason why Czechoslovakia was advocated by emigrants was because of a political-ideological concept of the Pan-Slavism. Though the concept has played a role in the motivations of Russian policy in East Europe and especially at the Balkans, the extent to which it contributed to the idea of Czechoslovakia is not agreed upon, but it surely influenced some thinkers. Pan-Slavism was used during the Great War to encourage some of the captured Slovak soldiers, at that time as soldiers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to instead fight against it. After Czechoslovakia became independent in 1918, however, the idea of Pan-Slavism was not strongly advocated for, losing favor with those who had supported it.

The Czech lands gained independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire first. Slovakia proclaimed its independence and desire to join the Czech country two days later. However, this process took more time. The Czech troops which had been in Slovakia were defeated by the Bolshevik army, which briefly occupied part of the country and installed a puppet Soviet Government. The Hungarian forces were able to force the Bolsheviks out of the country but ended up losing possession of the country after the 1920 Trianon Peace Treaty, which created the border between Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Part of the justification for the foundation of Czechoslovakia was to give the Czechs and Slovaks their own country, compared to the Austro-Hungarian Empire where they were denied rights due to their minority status. Nevertheless, due to the way that Czechoslovakia was established, it was to have its problems with minority populations (Germans and Hungarians) within its borders and choosing the best way of handling them.

Czechoslovakia was the Central European state which emerged on the political map as a consequence of the collapse of the Dual Monarchy (the Austro-Hungarian Empire). The country’s formal independence was declared on October 28th, 1918, and confirmed at the Paris Peace Conferences, on September 10th, 1919. The final borders are fixed by the 1920 Trianon Peace Treaty.

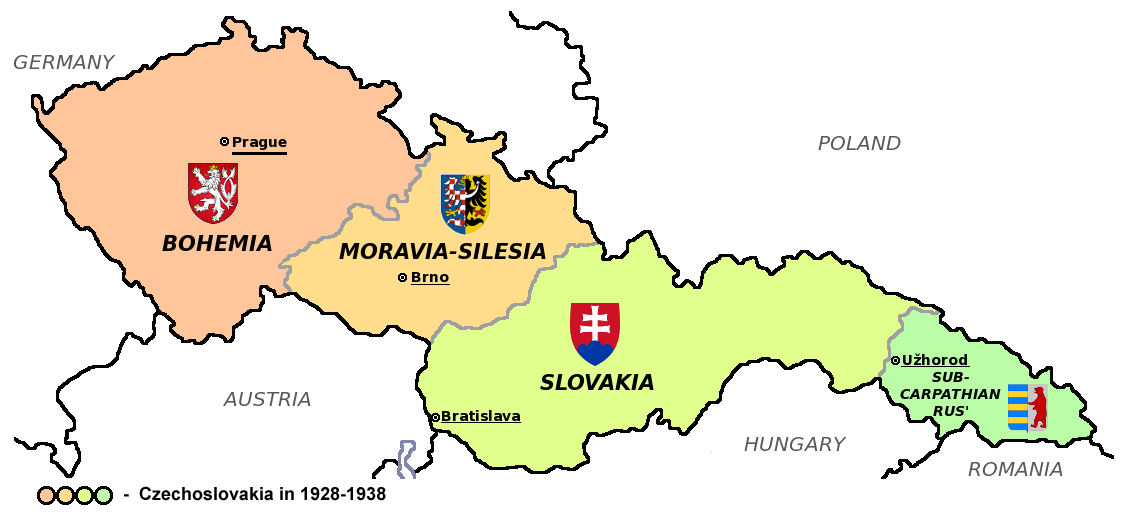

The country was composed of two different parts:

- The economically advanced historical regions of Moravia, Bohemia, and parts of historical Silesia, which made up the Czech lands (former part of Austria).

- The industrially backward Slovakia, including parts of the even poorer Carpathia (former part of Hungary).

The very fact was that the new state became extremely ethnically heterogeneous as consisting of 66% Czechs and Slovaks, 22% Germans, 5% Hungarians, and 0,7% Poles followed by other ethnic groups. Such ethnic background alone obliged the new state to pursue an extremally liberal policy for the very reason to reconcile its numerous minorities. This liberal trend was reinforced by its educated intellectual leadership under Thomas Masaryk and Edvard Beneš. Their liberal politics have been fully supported by the well-developed and prosperous middle class of the Czech lands.

In the 1920s, Czechoslovakia experienced greater economic development in comparison with all other Central European economies. Due to the Little Entente Pact backed by France and its good relations with Paris, the country succeeded to buttress its position in foreign affairs. Nevertheless, in the 1930s, after the Great Economic Depression in 1929−1933, it became extremely difficult to save the country from the rise of Nazism, fascism, and other forms of autocratic political systems that have been surrounding the country. The new Germany’s Nazi movement, in particular, attracted the Sudetenland Germans in north-western Bohemia, who started to demand more autonomy and self-government ever more aggressively. However, inter-ethnic grievances as well as existed from the Slovak part of the country. As the educated middle class was almost Czech, the Slovaks found themselves underrepresented in the political system of the country and, therefore, they started to demand more autonomy for the Slovak half of the state.

The Interwar Years and the question of the Sudeten Germans (1919−1938)

Czechoslovakia went from being part of a multi-national Austro-Hungarian Empire to being a country with sizeable ethnic minorities. The three largest ethnic groups in Czechoslovakia in the interwar period were the Czechs, at about 6.5 million, the Germans at about 3.1 million, and Slovaks at 2.2 million. The remaining ethnic groups included the Hungarians, Poles, Ukrainians, Roma, and others. The relationship between the Czechoslovak Government and the Sudetenland Germans was tense and remained so throughout all interwar years. The reason for this was that the Germans did not accept their inclusion within the new country after WWI, and feared that their identity would be lost. The Slovaks, on the other hand, were more accepting the new state for at least two crucial reasons:

- There was the belief that may not have gone far as Pan-Slavism but still advocated the Czechs and Slovaks being branches of the same family.

- Czechoslovakia was seen as a preferable alternative to being ruled by the Hungarians, under whom they had to deal with Magyarization and the prevention of the development of a Slovak national identity.

The Sudetenland Germans created a problem for the Czechoslovak Government due to their size and lack of commitment to the idea of the new state. One way in which the tension was reduced was by Czechoslovakia’s political stability and economic strength during the interwar years. As a matter of fact, the Sudetenland Germans faced a higher standard of living during that time than the Germans in Germany. However, this did not prevent the wide acceptance of Nazism from spreading to the region when the Nazis came to power in Germany. The Sudetenland Germans also developed strong anti-Czech policies, especially during WWII. The adoption of Nazism was in contrast to the political leaders of Czechoslovakia who, unlike many other countries during the period who attempted different types of autocracy, managed to maintain its identity as Central European liberal democracy.

The vigor with which Sudetenland Germans did not want to be a part of Czechoslovakia also led to the second problem. Two types of policies were pursued in order to reduce the risk of conflict arising from the Sudetenland Germans:

- One of these sets of policies had to do with autonomy. The Czechoslovak Government decided to not enter into a federation type of state organization. Such a decision was done for the purpose that the Sudetenland Germans would not gain more political power from which to further strain their relationship with the Czechoslovak Government. Nevertheless, this also meant that the Slovaks could not have more political and legal autonomy too. This may not have initially been a problem because of the lack of development of a Slovak identity and civil society during the centuries of Hungarian rule.

- However, the second type of policy contributed to the development of these, something the Czechoslovak Government had not anticipated. A way to strengthen not only the Czechoslovak Government against the Sudetenland Germans but to strengthen the country itself was to develop Slovakia and to promote a shared Czechoslovak identity. Firstly, if the Czechoslovaks were counted as one ethnic group within the country then the ratio of Czechoslovaks compared to the Sudetenland Germans would be larger than looking at just Czechs or Slovaks compared to the Germans. Secondly, an economically strong country was believed to diminish the potential for grievances against the Government.

Due to the lack of development on the Slovak side of the country, money traveled almost exclusively from West to East in order to develop the Slovak economy. Money also went into the development of schools and public institutions and contributed to the development of a Slovak intelligentsia.

Interwar Czechoslovakia was still not overcome by internal collapse, however, by the 1938 Munich Agreement, when the Sudetenland was annexed by Nazi Germany, and the lands inhabited by the Polish minority (Teschen) and Hungarian minority were annexed by Poland and Hungary respectively.

The Sudetenland Germans strongly supported the inclusion of Sudetenland into Germany, since they still retained a strong German identity. At the 1938 Munich Conference, leaders from four countries (Germany, France, UK, and Italy) met in order to discuss what to do about the Sudetenland. On September 30th, 1938, Sudetenland was incorporated into Germany. By giving Sudetenland to Germany, other countries were hoping that the German desire for more land would be satisfied. The Sudetenland had a large number of German citizens where roughly two-thirds of its population supported inclusion into Germany. However, it also brought into question the strength, and legitimacy of the Czechoslovak Government. Nazis working in Czechoslovakia had advocated for autonomy for the region. Instead, the Czechoslovak Government granted more minority rights but refused to designate Sudetenland as an autonomous region.

By losing it to Germany, the Czechoslovak Government was perceived as weak. By this time, the Slovaks had developed not only their class of intelligentsia but a more cohesive idea of Slovak national identity and independence. One of the crucial geopolitical consequences of the 1938 Munich Agreement was that it emboldened individuals who supported the creation of an independent Slovak state instead of weakened Czechoslovakia which did not get the European support for its territorial integrity.

Nevertheless, while on one hand the Slovak nationalists were emboldened by the loss of Sudetenland in the 1938 Munich Conference, they also now faced a dilemma. It was suspected that Nazi Germany would not be content with just the acquisition of the Sudetenland. The German idea of Lebensraum based on the acquisition of land for the German people, along with the expulsion or execution of other ethnic groups considered to be racially inferior, also led to the conclusion that the Nazis would seek to acquire more land. The Czech members of the common Government were strongly against Nazism and it was suspected that if the Germans defeated Czechoslovakia, policies instituted by the new German Government would harm all of the citizens of Czechoslovakia. However, the Slovaks had a way out of this predicament. The German Government made clear to the Slovaks that they would be willing to support the formation of an independent Slovak state instead of a common one with the Czechs. The Slovaks had to choose whether to stay part of Czechoslovakia or to proclaim their formal independence under the German patronage.

On March 14−15th, 1939, the German army invaded the rest of the historical Czech territories within Czechoslovakia with the creation of the German protectorate over Bohemia and Moravia. These two historical provinces became relatively autonomous, with a puppet President Emil Hácha. However, the Nazi German brutal administration suppressed the Czech educated and middle classes during the protectorate time (1939−1945).

WWII (1939−1945)

The decision of Slovaks during WWII to accept A. Hitler’s protectorate over quasi-independent Slovak state created one of the mutual grievances that existed between the Czechs and the Slovaks in the post-war decades. Due to fear of what the Third Reich would do to Slovakia if Czechoslovakia was defeated by Germany in the case of the war, Slovakia declared its quasi-independence and became a protectorate of Nazi Germany. However, that was not the extent of the Nazi impact on Slovakia. Instead, the Slovak nationalists adopted some of the Nazi sentiments. The President of Slovakia, Jozef Tiso, set up a quasi-Nazi state. The Czechs as well as the Jews were treated poorly by this new Government. The definition of what a Jew was also changed, from being a religious definition to now being an ethnic one. Such an antisemitic policy had several points. For one, it was felt to make it easier to separate Jews from the rest of the population. This definition also separated the Jews from the rest of the Slovaks ethnically and was used as justification for the poor treatment, and eventual deportation of the vast majority of Jews in Slovakia to the concentration and death camps, where the majority of them died. This included also children, whom J. Tiso believed should not be separated from their families, and so many of them went to the gas chambers with their mothers. Some Jews were not deported due to their importance in the economic functioning of the Government, but this did not protect them from poor treatment. There is some controversy about how much the Slovak Government actually adopted the tenants of Nazism, and whether this was due to pressure from the Nazi Government or whether or not the ideas were internalized by the Slovak political elite. Nevertheless, while the declaration of independence and protectorate status of Slovakia during WWII did create mutual grievances, it does not exist as a strong point of contention between the Slovaks and the Czechs today.

Following the murder of Reinhard Heydrich, the Nazi German rule of terror in the Czech lands climaxed in the revenge action of the destruction of the village of Lidice. R. Heydrich (1904−1942) was a German Nazi police general and one of the most ruthless Nazis. In 1934 he became chief of the Gestapo, before being promoted to chief of the internal security service by H. Himmler. R. Heydrich became appointed general of the police in 1941 and as such directly responsible for the execution of the policy of “Final Solution” of the Jewish Question in occupied Europe. In the same year, he became appointed Deputy Protector of Bohemia being assassinated in Prague by a Czech who was a British agent. In retaliation, Lidice, a Czech village, was destroyed by the SS and Gestapo on Jene 10th, 1942 when all-male inhabitants (160+) were shot, 192 women were deported to the concentration camp at Ravensbrück, where 52 of them died, and 96 children were deported to be Germanized in SS camps.

Nevertheless, although the Nazi German oppression and brutality have been severe, they remained at a level to be compared with the Nazi rule in occupied West Europe and is totally different in comparison with East and South-East Europe (for instance, the 1941 Kragujevac Massacre in Central Serbia compared with the Lidice case), and were not as brutal as in Poland or the occupied territories of the USSR. The reason for such practice partly was because of the Nazi reliance on the Czech labor force in the armament industry.

The transitional period (1945−1948)

At the end of the war, both Czechs and the Slovaks agreed to return to the pre-war arrangement of Czechoslovakia. After the war, the Government-in-Exile under Edvard Beneš returned to Czechoslovakia. The initial break with Czechoslovakia’s interwar liberalism in the politics and toleration of inter-ethnic relations arrived in June 1945, when Czechoslovakia became the first East European state outside both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union to carry out de facto ethnic cleansing by expelling the German and Hungarian minorities from the country.

The Sudetenland Germans were felt to be as responsible for the war as the other Germans, and with the support of the allies were forcibly deported after the war. With the most vocal minority against the existence of Czechoslovakia no longer existed in the country, there was a much better possibility of dealing with minority issues after 1948 by the new Communist Government. However, immediately after the war until 1948, the Czechoslovak Government had other problems that needed to be dealt with urgently. Two parties, the Communists and the democrats vied for power within the Government in Prague.

In the elections of May 1946, the Communist Party became the largest one with 38% of the voting body supporting it. The party’s leadership organized a cup in February 1948 with the creation of a Communist-one-party political system in Czechoslovakia. This became accelerated with many Stalinist-type political-ideological purges. Therefore, Czechoslovakia quickly and firmly came under the umbrella of Stalin’s USSR being adhered to the extremes of Stalinism even after the death of J. V. Dz. Stalin in 1953. In the coming years, human rights violations by the Communist regime with depended judiciary continued.

The Slovaks were unable to achieve a federal system of the state (like in post-war Yugoslavia, for instance) in part because the Slovaks were not united as one political party, but rather split off between the nationalist and the conservative parties. Those Slovaks who were believed to have supported the Nazis were dealt with in several ways. Some were held accountable by the Government, some left the country, and those who stayed in the country were not able to play a strong role in the Government. Due to the association between the conservatives and the Nazi Government during the war, the conservatives were not able to attract a large number of people for their party’s program. Many of the more liberal nationalists ended up joining the Communist party, where they were mainly focused on the preparation of the functioning of a Communist Czechoslovakia.

The time of Communism (1948−1989)

Communism was the main ideology of the Czechoslovak Government from the time when the Communists gained power in February 1948 until the Velvet Revolution in 1989. Under Communism, federalism was no longer an option. The Slovaks who were deemed too nationalistic by the Communist Government were often purged, through executions or through imprisonment. Even the Slovaks who had initially supported the Communist Government but still held some nationalist beliefs were not spared. The economy also shifted to a model promoted by the Soviet Union – command economy. Due to these efforts, the economy began to suffer, which led to a short-lived attempt at some small-scale liberalization both within the economy as well as within civil society but, however, such policy did not last long. When Antonin Novotny became a President in 1957, these liberalization policies were abandoned. Later, in 1963 there was some liberalization of the economy attempts as well as some of the restrictions on institutions such as education and the press, but political power remained tightly in the hands of the central Government controlled by the Communist party.

The country’s economy, which suffered little damage during WWII, became mismanaged and as a direct consequence, it led to the economic crisis in the 1960s. Growing unrest and public protests led to the final appointment of the reformer Alexander Dubček as First Secretary of the Communist Party in January 1968. In 1968, there was a wave of democratization in what came to be known as the Prague Spring (from January to August). A. Novotny was replaced by Alexander Dubček who advocated for more liberal policies in order to improve the economic conditions of the country. The reformist A. Dubček proceeded to transform the Communist Party and the state system for the sake to overcome the discontent and demonstrations created by twenty years of command economy and repressive one-party Government. He wanted to end unfair political trials and release or/and pardon all those citizens who have been unfairly convicted in political trials. The initial success of his policy was that press censorship ceased in March 1968, travel restrictions became eased, and elections to posts within the Communist Party had to be secret.

However, despite A. Dubček’s care to cultivate good relations with the Government of the Soviet Union, he totally underestimated the political, economic, and geopolitical challenges his reforms presented to the other members of the Soviet bloc, especially to the neighbors East Germany and Poland. The Communist Parties of these two countries had their own problems and challenges to legitimacy. What their leadership quite well understood is that those political and economic reforms in Czechoslovakia could finally result in the collapse of their Communist systems.

Nevertheless, A. Dubček’s attempts to bring political and economic liberalization threatened the status system in Communist East Europe during the Cold War 1.0 challenging hardline leaders of other Communist states. However, attempts at wide-scale change were abruptly ended when the Soviet Union (led by the Ukrainian Leonid Brezhnev) and some of the Warsaw Pact countries sent tanks and troops into Czechoslovakia to return to the policies before the Prague Spring which ended on August 20th, 1968. The troops of the Warsaw Pact entered Czechoslovakia without any resistance either by the army or the people. While this did succeed eventually in forcing a return to the repressive policies that had previously existed, it did not succeed in stamping out dissent. Instead, over the decades that followed, anti-Government demonstrations were sporadic showing that this had in fact not succeeded. In sum, the 1968 Prague Spring was over on August 20th, and the new hard-line Communist Party’s regime was established which was to rule Czechoslovakia for another twenty years till the 1989 Velvet Revolution.

The coming two decades till 1989 in which the Communist political orthodoxy became re-established combined with strict press censorship and an attempt to mollify political opposition with economic benefits. However, the latter was extremely difficult to be realized as economic growth was slow not least because of the effects of the oil price shocks in the 1970s., and the failure to invest in new technologies in a country which traditionally was reliant economically on its heavy industry (the Czech part). In the late 1970s, the political development of Czechoslovakia led to the creation of the Charter ’77 opposition movement, which at the beginning was an inspiration to dissident movements in other countries of East Europe. The movement provided the political leadership to which the people could look as an alternative to the Communist Government, at the historical time when the Communist regimes have been weakening their position in East Europe.

The Charter ’77 was a document signed by 243 people of whom the biggest number has been intellectuals. The document was addressed directly to the Communist Government of Czechoslovakia as a protest against the systematic violations by the state authorities against the fundamental human rights which have been guaranteed by the UNO and the Helsinki Conference, to both of which Czechoslovakia had subscribed. The document was delivered in 1977, and attracted during the following decade 2.500 signatures, despite the political prosecution and discrimination which public support for the text of the document attracted. On one hand, however, the real political influence of the Charter ’77 movement was limited primarily due to its restricted social base. Nevertheless, on the other hand, as the most articulate oppositional political movement in East Europe, it became quite known in the international environment. Many of its leaders, including V. Havel, have been active in political discussions at the time of the collapse of the Communist authority in 1989 (the Velvet Revolution).

The Velvet Revolution and the breakup of Czechoslovakia (1989−1993)

The 1989 Velvet Revolution is a term used in historiography to describe the peaceful transfer of political power in Czechoslovakia from the Communist party to the civil rights movement. There were waves of anti-Government protests in Prague and Brno from August to October 1989 that led to the Government’s eventual resignation. Nevertheless, those protests at the beginning have been repressed, but the state security forces became increasingly unable to stop the constantly growing number of the people who took part in the demonstrations.

The anti-Government organization called the Civic Forum, led by V. Havel was founded on November 18th, 1989 with the main logistic purpose to coordinate and organize the opposition forces with a political task to engage in negotiations with the Government. The Civic Forum organized a general strike on November 27th, 1989, which clearly showed that the Government lost any significant popular support, and as a consequence, it collapsed within the next several days.

By this time, Communism was not only weakening in Czechoslovakia but also throughout East Europe but Czechoslovakia triggered its final end. The political monopoly of the Communist Party became withdrawn on November 29th, 1989. The rule of the Communists ended in December 1989 with the Velvet Revolution, and a Government under the leading Charter ’77 dissident Václav Havel (1936−2011) became established. The two most prominent opponents of the Communist authority during the last twenty years entered the office: A. Dubček became elected Speaker of Parliament, and on December 29th, 1989 V. Havel became a new President of Czechoslovakia.

The Velvet Revolution was complete being confirmed by the free elections of June 8−9th, 1990, in which the leaders of the Velvet Revolution were endorsed. At the beginning of the 1990s, Czechoslovakia fought to reclaim the liberal interwar tradition in political life and economic prosperity.

At the moment, it was a general opinion and feelings that the command economies of the Communist countries did not bring big economic benefits to their citizens but, instead, created hardships that motivated people to protest against their Governments. The Soviet Union saw that the Communism was not going to last, and removed the last of their military and hardware from Czechoslovakia in 1991. Shortly thereafter, elections were held, which showed a strong divide in the politics of the two sides of the country.

While the division of the country was not thought by outsiders to be mutually desired, politicians from both the Czechs and the Slovaks advocated for the separation of the two countries. The central Government in Prague was unable to prevent a growing sense of nationalism in the Slovak part of the country, which started even during the last years of the Communist rule. Unable to reach a political agreement between a federal or confederate form of the common state, Czechoslovakia finally peacefully split into two internationally recognized states on January 1st, 1993: the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic.

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics, and international relations.

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS