Views: 1073

Introduction

The aim of this article is to shed new light on the question of how the configuration of post-war Central and South-East Europe was shaped during WWII by the USSR through its relations with the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (the CPY). Relationships between the CPY and the Soviet Union in 1941−1945 depended on the concrete military situation in Europe, and on the diplomatic relationships between the Soviet Union and the other members of the anti-fascist Alliance. For that reason, the Soviet Union and the CPY were cooperating in two directions during WWII. The concrete military situation in the battleground of the Soviet Union after the outbreak of the “Barbarossa” in June 1941, and, the Soviet political plans after the end of the war in terms of the reorganisation of Europe determined their interconnections.

The complexity of relationships between the Soviet Union and the CPY has to be seen through the diplomatic relations between the USSR and the officially recognised by Moscow of the Yugoslav Government-in-exile located during the war in London. The Soviet policy toward Yugoslavia was divided into two spheres. The first concerned the CPY and the second involved the Yugoslav Government in London. The Soviet-Yugoslav relations depended primarily on Moscow’s relations with London and Washington, particularly in regard to the question of the opening of a second (Western) military front in Europe. During the course of the war, when the opening of the second front in Europe was being debated, the Balkans was mentioned as a likely place, but the arguments in favour were more political than of military nature. For the Soviets, the opening of a second front was to be the prelude to final military operations, during which the strategy for shaping post-war Europe would have to be decided upon. However, for each member of the Alliance, it was clear that any hasty step might have caused new rifts among the allies, especially between London and Moscow. In view of this fact, one can amply understand the complexity of the CPY–Soviet relations during the war years.

The clash of two historiographies

The CPY-USSR relationships were carried out by the Executive Committee of the Comintern. The direct link between the CPY and the Comintern was the secret radio connection between Josip Broz Tito (appointed by J. V. Stalin as the General Secretary of the CPY in 1937), and George Dimitrov, the General Secretary of the Comintern. On the other hand, relations between the USSR and the Yugoslav Government-in-exile were officially conducted by legations.[1]

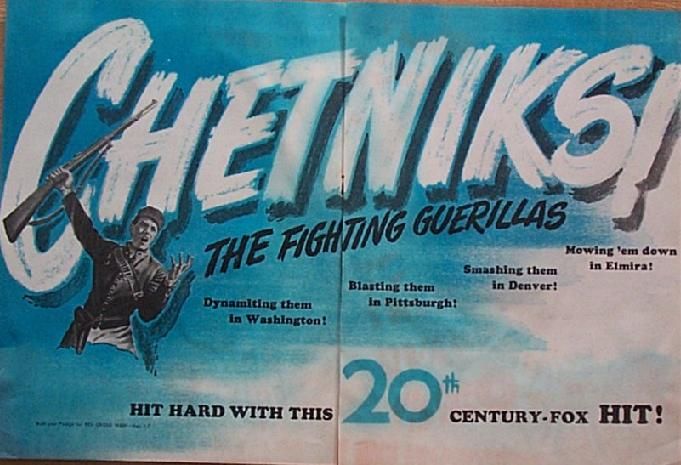

Relations between the CPY and the Soviet Union during WWII developed gradually. They started with the supply of military and medical materials for the so-called National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia (the NLAY), led by the Yugoslav communists, and continued in direct military cooperation in 1944−1945. The main purpose of this Soviet support was to ensure the success of the CPY in taking power and introducing socialism in Yugoslavia. The fundamental aim of Moscow’s Yugoslav policy, i.e. its support of J. B. Tito’s partisans and his CPY, was to bring socialist Yugoslavia into the post-war Central-South-East European community of Pax Sovietica controlled and governed by the USSR. For that reason, although the other members of the Alliance, the USA and the UK, supported both J. B. Tito’s partisans (communist forces) and Dragoljub Draža Mihailović’s the Yugoslav Army in the Motherland (the YAM) or known as the chetniks (royal forces), the Soviet Union supported only the Yugoslav communists and their Yugoslav People’s Liberation Army, especially during the final stage of the war. Even though a second front was not opened in the Balkans, the final operations could not bypass this part of Europe since the local people, particularly the Serbs from Yugoslavia had been fighting there from May 1941. The Soviet Red Army made use of the Yugoslav partisan movement under the communist leadership and during the last eight months of the war succeeded through military co-operation to put Yugoslavia under its own political protectorate. It should be said that for Moscow, the Yugoslav partisan movement and armed fighting led by Tito (basically only against the D. D. Mihailović’s legal and internationally recognized the YAM) had more political than military significance. In a new guise and in new historical circumstances, Central and South-East Europe once more found itself directly in the sphere of the conflicting interests of the global Great Powers. Throughout the war, the allies clashed in their Central European and Balkan policies and in their attempts to influence the national liberation struggles within this portion of Europe. The members of the Alliance were convinced that they could resolve matters by striking bargains among themselves. The result of this conviction was the division or “tragedy” of Central and South-East Europe designed in Tehran in 1943 and confirmed in Yalta and Potsdam in 1945.[2]

Relations between the CPY and the Soviet Union from 1941 to 1945 are variously explained in the Yugoslav and the Soviet historiography. In the first, the chief conclusion is that J. B. Tito’s partisan movement was independent, in other words, not under the supervision of Moscow. The CPY and its partisans were not a “prolonged hand” of J. V. Stalin and they did not pursue the Soviet policy of spreading the socialist revolution around the world. Besides, the Yugoslav Titoist historiography pointed out that the military help of the USSR given in autumn 1944 to J. B. Tito’s partisans was not the decisive factor which crucially helped the CPY to take political power in whole Yugoslavia (firstly in Serbia in October 1944). The main proponent of this view is Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980) himself, whose war memoirs, published in his Sabrana djela, (All Works, Belgrade 1979), has the main aim of showing J. B. Tito’s independence from J. V. Stalin. The best representatives of such an attitude in the Yugoslav historiography are: Branko Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988, (History of Yugoslavia 1918−1988) second volume, Belgrade 1988; Miodrag Zečević, Jugoslavija 1918−1992. Južnoslovenski državni san i java (Yugoslavia 1918−1992. South-Slavic state dream and reality), Belgrade 1993, and Vladimir Velebit, Sjećanja (Memoirs), Zagreb 1983.

However, as opposed to the Yugoslav historiography, the most common Soviet and more accurate version of those relations hold that the CPY during the whole war strongly depended on Moscow. The actions of the Yugoslav communists were directed by J. V. Stalin in order to carry out his policy of the “world socialist revolution.” According to this historiography, it was only the Soviet military help given to J. B. Tito in October 1944 which enabled him to win political power over all of Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, one of the main defects in both of these historiographies is that they minimised the role of the Yugoslav Royal Government-in-exile and of the US’s and the British diplomacy in relations between J. B. Tito and the Soviet Union during WWII. This defect was only partially overcome in the book: Jugoslovensko-sovjetski odnosi u drugom svetskom ratu (1941−1945), (Yugoslav-Soviet Relations during the Second World War (1941−1945), Belgrade 1988, written by Nikola B. Popović.

Therefore, it is necessary to undertake an analysis to explore relations between the Yugoslav communists and the Soviet Union in the years 1941−1945 setting out three new hypotheses which are based on the Yugoslav and the Soviet historical sources from WWII:

Firstly, the communist uprising in Yugoslavia in July 1941 was ordered by the Comintern and was organized in favour of the Soviet Union. This hypothesis derives from the view that J. B. Tito was sent from Moscow in 1937 to Yugoslavia as a new General Secretary of the CPY with the purpose of preparing the party for taking power in Yugoslavia with the Soviet help. This was to be carried out under the pretext of resisting the occupiers. The actual goal was to carry out J. V. Stalin’s policy of spreading the Soviet influence in Central and South-East Europe under the pretext of “people’s” (socialist) revolution. The final result of J. V. Stalin’s policy was to establish the Pax Sovietica within the eastern portion of Europe.

Secondly, J. B. Tito’s partisan movement was, in fact, independent from Moscow far until 1944 as material and military support is pointed. There were two reasons for this: 1) J. V. Stalin could not give real military support to J. B. Tito before 1944 because of his relations with the UK and the USA and 2) only in 1944 the appropriate transport conditions for the Soviet support delivered to J. B. Tito’s partisans were technically established. However, as it will become evident, J. B. Tito was receiving overwhelming material support from Moscow in 1944 and 1945 in what turned out to be the crucial situation of conquering Belgrade in October 1944 and after that to take political power in all of Yugoslavia.

Thirdly, the main character and aim of J. B. Tito-led partisans’ actions was a socialist revolution but not a fight against the Nazi-fascist occupiers as such.[3] What I am in effect arguing is that this aim under instructions given from the Comintern was not so publicly propagated by J. B. Tito’s partisans in order to avoid upsetting Moscow’s Western allies.

Origin of the Yugoslav uprising and civil war and the Soviet Union

In occupied Yugoslavia (partitioned by Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Italy after twelve days of the April War of 1941) popular resistance to the invading forces took the form of an armed uprising. This uprising started in June 1941 when the local Orthodox Serbs took arms on the territory of the newly established Nazi-fascist Independent State of Croatia (the ISC) to defend themselves from the Croat-Bosniak massacres orchestrated by the Nazi-fascist Ustashi regime in Zagreb. At that time, however, the CPY was keeping silent about the beginning of the Serbian genocide in the ISC and taking no single action to protect unarmed Serbian civilians.

However, the CPY called the Yugoslavs to take arms against the occupiers only after the requirement by the Comintern what happened as a consequence of the German attack on the USSR in late June 1941. Basically, the communist “uprising” in the form of socialist revolution was quickly followed by the Yugoslav civil war which was, in fact, initiated early in July 1941 when the Central Committee of the CPY called upon the peoples of Yugoslavia to take up arms, and in the course of that same year the uprising spread to all parts of Yugoslavia, but in the first instance to the parts of the country settled by the Orthodox Serbs who did not make crucial difference between the patriotic war of liberation from the socialist revolution advocated by the CPY. The proclamation of the uprising of all Yugoslav people was populated by the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPY on July 4th, 1941, the day after J. V. Stalin’s speech to the Soviet people on the radio. According to the politically coloured post-war Titoist historiography, this proclamation became an inspiration to transform previous sabotage actions to the partisan war against occupiers.[4] From that moment the passive conduct of the CPY, influenced by the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact (August 23rd, 1939) was transformed into a “mobile position”. Considerable territory in West Serbia was liberated by joint forces of D. D. Mihailović and J. B. Tito who collaborated during the first months of the uprising until the end of September 1941 when the communist detachments started to attack the YAM. Both sides established control over certain liberated territories. The most important partisan-controlled liberated territory was around the city of Užice where they proclaimed the Soviet republic. After the proclamation of the liberated territory of the Soviet Užice Republic, the Supreme Headquarters of the Yugoslav partisans under J. B. Tito’s command established itself there.[5]

The CPY had direct radio communication with the Comintern which was facilitated by Josip Kopinič, a very close comrade of J. B. Tito.[6] J. Kopinič was sent by the Comintern to Yugoslavia in February 1940 to “carry out a special task”.[7] The headquarters of this radio was located in Zagreb and J. Kopinič was sending his reports to Moscow from there until 1944. J. B. Tito started to use this radio from January 1941 in order to inform Moscow personally.[8]

This radio was part of a Soviet agency in Yugoslavia which was established in summer 1940. The Soviet military attaché in Yugoslavia set apparatus with a secret code to the correspondent of the United Press, Miša Brašić, in June 1941, when the Soviets left Belgrade after the German attack on the USSR.

After the outbreak of J. B. Tito-led partisans’ uprising in July 1941, this radio-apparatus was used by the Supreme Headquarters of the partisan units.[9] Moreover, in the summer of 1941, the CPY maintained connections with Moscow with three independent radio-apparatuses operated by Josip Kopinič in Zagreb and Mustafa Golubić and Miša Brašić in Belgrade. It is generally acknowledged that due to them, the Comintern collected very important information about the political and military situation in Yugoslavia during the critical period of the German attack on the Soviet Union (June-December 1941).[10]

The Soviet Union was the only country which broke off diplomatic relations with the Yugoslav Government-in-exile (May 1941). Acting in this way, the USSR recognised de facto the occupation and partition of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by Italy, Germany, Hungary, and Bulgaria as well as the existence of the Nazi-fascist Independent State of Croatia. However, in July 1941 the Soviet Union restored diplomatic relations with the Yugoslav Royal Government in London. Consequently, it was beneficial for Moscow to have double relations with Yugoslavia: one was public and legal (with the Yugoslav exiled Government in London) and the other one was secret and nonofficial (with the CPY as one of the sections of the Comintern). The Soviet historiography claimed that the Comintern, as an international organisation, was independent (did not work under the orders from the Soviet Government of J. V. Stalin). However, the Yugoslav historiography disagrees with this opinion. It stresses the fact that the Comintern was located in the Soviet Union which was dominated by J. V. Stalin and that the Comintern was an “extended hand” of the official Soviet Government. The Yugoslav historians have concluded, like the Western historiography, that the policy of the Comintern was precisely the policy of the Soviet Government.

Moscow interfered and supported any resistance movement in Europe which could weaken the German military pressure on the Eastern Front, and bring advantage to the military situation of the Soviet Union. Consequently, the Balkans, Yugoslavia, and the CPY were seriously taken into consideration by J. V. Stalin, the Comintern, and the Soviet Government. The Soviet Union’s policy in the interwar time (up to 1935), based on J. V. Stalin’s desires, was to destroy the Kingdom of Yugoslavia because as being a member of the Western “Versailles system” Yugoslavia participated in blocking the Soviet influence in Europe. The Soviet policy towards Yugoslavia was carried out through the Comintern, in fact through the CPY as member of the Comintern.[11] The Comintern required from the other communist parties to undertake all measures necessary in order to weaken the Nazis’ attacks on the Soviet Union. It was implicitly emphasized immediately after the outbreak of “Barbarosa” on June 22nd, 1941, when the Executive Committee of the Comintern sent a message to the Central Committee of the CPY informing it that the defence of the Soviet Union was the responsibility of the other enslaved nations and their leaders – the communist parties. The Comintern required that during the war, any local contradictions and conflicts should be postponed and replaced with only the fight against fascism.[12] This Comintern demand implied that the CPY should temporarily halt the call for class struggle and unite all forces for the fight against Nazism and fascism.[13]

It can be argued, on the basis of historical sources, that the uprising in Yugoslavia, organised by the CPY in the summer of 1941, was ordered by the Comintern (the Soviet Government behind it) to reduce Nazi military pressure on the Eastern Front. This was manifested in a telegram of the Comintern sent to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia at the end of July 1941. This telegram answered J. Kopinič’s reports to Moscow about the situation within the Communist Party of Croatia. The Comintern stated that all members of the CPY were obliged to join the army, to defend the Soviet Union if it would be necessary and to give their lives for “the freedom of the Soviet Union”. Every member of the party was expected to be a soldier of the Red Army.[14] In the Announcement to the Montenegrin people at the end of June 1941 issued by the Provincial Committee of the CPY for Montenegro, Sandžak, and Boka Kotorska, it was written that “the biggest guarantee for success for national freedom in the fight against the occupiers is the powerful and almighty Red Army and the revolutionary forces of the international proletariat…”.[15] The Comintern, during this period of the war, even required from the Yugoslav partisans that they collaborate with D. D. Mihailović’s royal chetnik forces in order to be able to fight the Germans.[16] Thus, J. B. Tito attempted to enlist the cooperation of the chetniks under Colonel (later General) Dragoljub Draža Mihailović who was located in a nearby part of Serbia in joint fighting against the enemy. However, after the initial bilateral cooperation, the chetniks supported by the Royal Yugoslav Government-in-exile in London and the UK firstly provoked and later (in November) openly attacked by J. B. Tito’s partisans fought back acting against the partisan detachments during the German offensive against the liberated territory in November and December 1941. On this way, J. B. Tito’s military units started the civil war in Serbia with the final aim to occupy it (what they finally succeeded in October-November 1944 but only with direct military assistance by the Red Army after their crossing the Danube River from Romania).

The British initial strategy concerning Yugoslav affairs (i.e. the civil war) was to give support to that movement that would ensure the restoration of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia after the war. The enigma, which liberation movement official London would support, was resolved in the autumn of 1941 when Great Britain was beginning to send military missions to the Supreme Command of the YAM. Not a single British or Soviet mission at that time was sent to the Supreme Headquarters of the partisan detachments.[17] Nevertheless, the British attitude about the Yugoslav civil war (i.e. the struggle between the partisans and the chetniks) was changed after the Soviet victory over the Germans in the Stalingrad battle in early 1943. As it became clear for London that after Stalingrad the Red Army would drive further toward Central Europe and the Balkans, the British Government decided to make direct contacts with J. B. Tito in order to increase its own and decrease the Soviet influence among the Yugoslav partisans. The purpose of this revised British policy in Yugoslavia was not to allow Moscow to establish its full domination over post-war Yugoslavia and to use J. B. Tito for the British benefits in the region after the war (what in reality happened since June 1948 onward). Consequently, in April 1943 the first British mission was sent to J. B. Tito’s NLAY, but afterwards, they continued to arrive regularly and included even American military officers. The competition over Yugoslavia among the allies continued in early 1944 when the Soviet Union also sent a military mission to J. B. Tito.[18]

Moscow and the question of the socialist transformation of Yugoslav society (1941‒1942)

The intention of the Yugoslav communists to achieve a social transformation of Yugoslav society as their final goal in the civil war in Yugoslavia (1941−1945) was indirectly stimulated by J. V. Stalin’s speech on November 7th, 1941, when he predicted the end of WWII in the following year (i.e., defeat of Nazi Germany). This J. V. Stalin’s statement was instigated by successful Soviet counterattack in the battleground in front of Moscow.

J. B. Tito considered this J. V. Stalin’s speech to be a signal to prepare the CPY for taking power in Yugoslavia before the end of the war. However, J. B. Tito’s partisans faced defeat by the German Nazis in West Serbia in December 1941, which postponed achievement of his ultimate political aims in Yugoslavia.[19] Nevertheless, J. B. Tito always emphasised that the CPY in its struggle for power in Yugoslavia would get support only from Moscow.[20] In order to encourage partisan units after their failure with Nazi troops in West Serbia, J. B. Tito continued to believe and propagate that he would gain a quick victory by the support of the Soviet Union against the Germans. This strategy influenced J. B. Tito to rearrange the organizational structure of both the Yugoslav communists and their partisan units according to the Soviet model. The Partisan detachments, in other words, became reorganized according to the Soviet norms with the Soviet symbols and a political-commissar structure. In liberated territory (the Soviet Užice Republic in West Serbia) the revolutionary People’s Liberation Councils were formed on the model of the soviets in the USSR.[21]

Specific features of the war of liberation and the reintegration of Yugoslavia include the fact that the territories “liberated”[22] by J. B. Tito’s partisans became established as the communities of a nation at war, which had no direct links with the previous local authorities in the old system of governing that had collapsed in April 1941. The CPY as the mobilizing and organising force for the revolutionary war adopted the principle of the soviets in order to politically elaborate a strategy for the declarative emancipation and reintegration of post-war Yugoslavia. In many parts of Yugoslavia (Montenegro, Slovenia, Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina) the local committees of national liberation (or national liberation and revolutionary councils) were created on the liberated territories to perform administrative functions. But, all of them were organised and functioned according to the Soviet model. Consequently, on November 16th, 1941 the Supreme National Liberation Committee of Serbia was set up on the liberated territory of the Soviet Užice Republic.

Following the example in Serbia, in February 1942 the National Liberation Committee of Montenegro was formed on the liberated territory of Montenegro. Furthermore, the creation of a special revolutionary-striking military unit called “The First Proletarian Brigade” was formed exactly on J. V. Stalin’s birthday (December 21st) in East Bosnian village of Rudo in 1941. However, such revolutionary actions by J. B. Tito were criticised by the Comintern which, orchestrated by the Soviet Union, tried to stop J. B. Tito’s “socialist revolution” at that moment since the Soviet Government attempted to keep positive diplomatic relations with its Western allies. This caused distant relations between the USSR and the CPY for the latter’s achievement in “the socialist revolution” in Yugoslavia. The Comintern took all responsibilities to detach J. B. Tito’s actions from the Soviet policy in order not to deteriorate the British and American relations with the Soviet Union. This Comintern position was aimed to disband the suspicions of Great Britain and the USA about the partisans’ socialist revolution and its communist character in Yugoslavia.

The “patriots” and the “collaborators”

Relationships between the Soviet Government and the Yugoslav Royal Government-in-exile in London, which in the eyes of the allies represented the legal Government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, became seriously complicated in the summer of 1942. The reason for this was the question of the chetnik movement in Yugoslavia (the YAM), led by General Dragoljub Draža Mihailović and officially supported by the Yugoslav Government-in-exile.

On August 1st, 1942, the Soviet Government published the Resolution, which was mistakenly represented as written by the “patriots” from Montenegro, Boka Kotorska, and Tjentište but, in fact, by the propaganda machinery of the CPY. This document detailed the “collaboration and treachery” of General Draža Mihailović. For the first time, the Soviet media published such kind of resolution. Previously Soviet newspapers described only the partisan fight and their alleged military successes (which in the majority of cases were done, in fact, by the chetniks), but nothing was mentioned about the chetniks and their alleged “treacherous activities”.[23]

The Yugoslav Royal Government in London officially protested to the Soviet ambassador to the UK. This diplomatic protest inspired the Soviet Government to write the Memorandum handed to S. Simić, the Yugoslav ambassador in Kujbishew, on August 3rd, 1942. Presenting this Memorandum, the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs overtly uttered its opinion that General D. Mihailović had been a collaborator what indirectly meant that J. B. Tito was labelled as a patriot. The Memorandum provided the “facts”, received from J. B. Tito’s partisans, about D. D. Mihailović’s collaboration with the Germans and the Italians in Dalmatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Montenegro.[24]

This announcement of the Soviet Government indicates the recognition of its relationships with the CPY, on the one hand, and the changing relationships with the Yugoslav Royal Government in London, on the other. The counter-Memorandum of the Yugoslav Royal Government (August 12th, 1942) explained the chetniks’ activities against the occupiers and tried to improve the deteriorating diplomatic relations with Moscow.[25] However, the Soviet Government decided to rupture relations with officials of the Royal Yugoslav Government-in-exile due to the “collaboration” of the YAM with the Germans and the Italians.

Preparations for the 1943 Tehran Conference

In 1942, J. B. Tito requested permission from the Comintern to discredit publicly the Yugoslav Government-in-exile and its protege in Yugoslavia – General D. D. Mihailović. J. B. Tito’s final intention was to receive international support in order to replace the Yugoslav Royal Government in London as the only legitimate and internationally recognized political representative of the Yugoslav people. The leader of the Yugoslav partisans had been waiting for the reply from Moscow during the whole of 1942 and 1943. Nevertheless, in the meantime, a favourable moment for public dismissal of General D. D. Mihailović and his proponents in London did not occur.

Ultimately, J. B. Tito decided to make use of the meeting of the “big three” at the Tehran conference for his political aim to present himself and his partisan movement allegedly as the real and only moral representatives of the Yugoslavs. J. B. Tito organized the second session of the so-called Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (the ACNLY) in the Bosnian town of Jajce (November 29−30th, 1943) on the territory of the ustashi-run ISC, exactly coinciding with the sessions of the Tehran conference. The ACNLY, however, when was formed in November 1942 in the Bosnian town of Bihać (also on the territory of the ISC), did not have any prerogatives of a supreme governmental organ because of the current foreign policy considerations.

But, one year later, conditions were changed and the second session of the ACNLY adopted far-reaching decisions connected with the establishment of the new (socialist) Yugoslavia. The “people’s deputies” of the ACNLY decided to create the National Committee for the Liberation of Yugoslavia (the NCLY) which would play the role of a new (Titoist) Yugoslav Government. At the same time, the ACNLY was transformed into the people’s assembly. The return of the Yugoslav king and the Royal Karađorđević family to Yugoslavia was forbidden until the war was over. The question of the political structure of the state (republic or monarchy) was supposed to be discussed after the liberation of the country. The federal structure of future Yugoslavia was proclaimed in advance. The federal internal structure of Yugoslavia, instead of the previous centralist model (up to August 1939), was propagated by the Yugoslav communists even before the war broke out in April 1941. For the Yugoslav communists, federalisation of the country was designed from 1937 onward as one of the crucial achievements of socialism. They took the Soviet Union’s federal model of internal state’s organisation as an example for the federal organisation of socialist Yugoslavia.[26] For the Yugoslav communists, a federal organisation of Yugoslavia was a cornerstone of a new union of “liberated” nations.[27]

While Moscow disapproved the creation of the ACNLY (November 26−27th, 1942) because of possible negative reactions from the Anglo-American side,[28] convocation and the legislative work of the second session of the ACNLY a year later were supported by Moscow.[29] From the very beginning of the war, J. B. Tito strongly insisted that the Soviet Government would recognize the partisan units in Yugoslavia as the regular army of all Yugoslav nations. In J. B. Tito’s mind, this recognition was supposed to be followed by a Soviet military mission sent to the Supreme Headquarters of the Yugoslav partisans’ National Liberation Movement of Yugoslavia.[30] J. B. Tito’s main diplomatic goal in the autumn of 1943 was to obtain from Moscow a public recognition of the alliance between the Soviet Government and the CPY.

To be sure, according to relevant historical sources, J. B. Tito utilised the preparation for the Ministerial Conference in Moscow between the USSR, the USA and Great Britain (held from October 19th to October 30th, 1943) to present his war aims in Yugoslavia to the Soviet Government. The leader of the Yugoslav partisans sent a message to G. Dimitrov (October 1st, 1943) informing the Soviet Government that:

- The Yugoslav National Liberation Movement recognizes neither the Yugoslav Royal Government in London nor the Yugoslav king because they supported D. D. Mihailović – “a collaborator and traitor of the Yugoslav nation”.

- The National Liberation Movement would not allow the Yugoslav Government-in-exile and the Yugoslav king to return to Yugoslavia because their arrival in Yugoslavia could give rise to the civil war in the country.[31]

- “The sole legitimate Government at the present time is represented by the national liberation committees, headed by the Anti-Fascist Council”.[32]

J. B. Tito in the same telegram presented his main revolutionary (socialist) claims to the Comintern as well. The message influenced the Soviet Government and during the Moscow Ministerial Conference (that was the preparation for the coming Tehran Conference) the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs V. M. Molotov demanded from the USA and the UK two things:

- To send a Soviet military mission to the Supreme Headquarters of the National Liberation Movement of Yugoslavia.

- To establish a military base in the Middle East in order to supply war materials to J. B. Tito’s partisans.[33]

J. B. Tito’s telegram, sent to G. Dimitrov, proves that the Soviet Government was well acquainted with the revolutionary aims of the National Liberation Movement of Yugoslavia. In the autumn of 1943, Moscow recognized the revolutionary claims of the CPY[34] giving J. B. Tito a “green light” to prepare the Jajce’s session of the ACNLY. It is known that the official Soviet Government in Moscow was using the Comintern for its political purposes. Because the Comintern did not answer J. B. Tito negatively about his intention to hold the ACNLY’s session in Jajce with an already designed schedule of work and prepared political decisions, one can only conclude that the Soviet Government sustained J. B. Tito’s intention to change the political system in Yugoslavia by revolutionary means.[35] For that purpose, regular reports of the Soviet officials on this region expressed the view that the CPY appeared like the only political power in this country which was capable of restoring the Yugoslav state. In the backing of this Soviet policy to manipulate the CPY in order to create a new satellite, a socialist Yugoslav state, was the Soviet geopolitical aim to establish its own political domination over Central and South-East Europe at the end of WWII. Socialist Yugoslavia (or Titoslavia) would play a very important role in J. V. Stalin’s geopolitical concept of the Pax Sovietica Commonwealth as the country connecting Central and South-East Europe’s territories under Moscow’s control and guidance.

There are indications from the sources that J. V. Stalin designed for Yugoslavia a leading role among the post-war Balkan member-countries of the Soviet commonwealth. Such indications can be found in Svetozar Vukmanović-Tempo’s memoirs Borba za Balkan (Struggle over the Balkans). Specifically, from March 1943 onwards (i.e., immediately after the Red Army defeated the Germans at Stalingrad) S. V. Tempo was working to set up a joint Balkan headquarters to coordinate military operations in the border regions of Yugoslavia, Albania, Bulgaria, and Greece against the Germans and the Italians. The command of the joint Balkan communist forces would be given to the Yugoslav communists, a sign that post-war Yugoslavia would play a chief role among other Balkan members of the Pax Sovietica Commonwealth. S. V. Tempo was working in haste “especially considering the fact that the landing of allied troops from Africa in the Balkan Peninsula was expected any day, and this would have greatly affected the balance of power in each Balkan country. There was no time for delay!”[36] However, developments did not take the expected course, since the Anglo-American forces invaded Sicily instead of the Balkans and later on South Italy. The idea of a Balkan Union under the Soviet supervision seemed to be realized in 1946−1947 when J. B. Tito and G. Dimitrov negotiated upon a Yugoslav-Bulgarian Confederation. At last, the idea turned out to be quite illusory in 1948−1949 with the J. B. Tito-J. V. Stalin’s confrontation and the Yugoslav expulsion from the Pax Sovietica Commonwealth by J. V. Stalin’s decision.

Tehran and Yugoslavia

The Tehran Conference was held between November 28th and December 1st, 1943 as an inter-allied meeting between three leaders of the anti-fascist coalition – W. Churchill, F. D. Roosevelt and J. V. Stalin. The demand for the opening of the second (Western) front in France in the summer of 1944 by the Soviet leader was coordinated with plans for a Soviet summer offensive in 1944. The three leaders discussed as well as the establishment of the OUN after the war. However, J. V. Stalin pressed for a future Soviet sphere of influence in the Baltic States and East Europe. Finally, the Soviet leader indicated Soviet willingness to join the war against Japan in Asia-Pacific after the German defeat in Europe.[37]

One of the important agreements of “the big three” in Tehran was to give aid to Ј. Б. Tito’s NLAY which practically meant that assistance to General D. D. Mihailović and his royal chetnik movement was ended. The Western allies obviously reversed their attitude towards events in Yugoslavia in view of the successes of the NLAY. The British as well were at that time becoming more interested in the armed movements in other Balkan countries with a view to the opening of a second front. However, agreement on aid to the NLAY became mostly beneficiary to the Soviets since the Red Army could give this aid faster than the British or the Americans. As a result, decisive Soviet influence in Yugoslavia at the last stage of the war was expressed by way of material support for the Yugoslav communists.

The Soviet support given to J. B. Tito’s combatants had four features:

1) War equipment and material.

2) Medical aid.

3) Financial support.

4) Support for the education of officers of the NLMY.

These Soviet provisions had a material and an ideological basis. During the war,, the NLMY did not have any serious factories for the production of war material at its own disposition for the sake to win the civil war. Therefore, that is the reason why the CPY and the Supreme Headquarters of the NLMY applied for material support from the Allies. However, the NLMY could expect this support only from the Soviet Government, because the USA and the UK favoured the chetniks of General D. D. Mihailović until the summer of 1944. The ideological reason stays in the hopes of the Central Committee of the CPY that Moscow is the natural (political and ideological) ally of the Yugoslav communists.

Nevertheless, the first consignments and medical materials were received from the Anglo-American side as part of their anti-Nazi program in June 1943. The Soviet Union delivered its first material support to J. B. Tito’s NLMY in March 1944[38] as a direct consequence of the Teheran Conference. It came after the visit of a Soviet military mission to the Supreme Headquarters of the NLMY on February 23rd, 1944, as the Soviet answer to J. B. Tito’s requests.[39] The Soviet Government was forced to react to possible Anglo-American power in Balkans immediately, in order to prepare the soil for its own sphere of influence in Yugoslavia, Central, and South-East Europe after WWII.

The Soviet Union increases its domination over the National Liberation Movement of Yugoslavia

A great success of J. B. Tito came when the Soviet State’s Committee of Defence decided on September 7th, 1944 that weapons and equipment for twelve infantry and two air-divisions would be transferred to the NLMY. This military aid was contemplated during the conversation between J. B. Tito and J. V. Stalin in Moscow from September 21st to 28th, 1944.[40] In order to fulfil this decision, the Soviet Government organized a military base in Romania (Craiova). The Soviets continue to deliver war material to the Yugoslav partisans from Bari and started to do it in autumn 1944 as well from Sofia (with trucks) and Craiova (with aircraft and trains). Some military help came also from the Headquarters of the Third Ukrainian Front. During October 1944, from all these Soviet military bases, 295,000 tons of war material was transferred to the NLMY. It can be claimed that this huge Soviet military support, sent to the Yugoslav partisans in October 1944 played a crucial role in the battle for Belgrade (October 18th−20th, 1944). After the Belgrade Operation and the taking of the Yugoslav capital followed by the establishment of their own military and political control, J. B. Tito’s partisans finally won a victory over D. D. Mihailović’s chetniks. As a result, the Yugoslav civil war was resolved in J. B. Tito’s favor with great and crucial Soviet military support. After the Belgrade Operation, the Soviet Government started to send to J. B. Tito food shipments ordered by J. V. Stalin on November 20th, 1944. The first Soviet food aid, comprising 50,000 tons of grain, was delivered to Yugoslavia at the begging of December 1944.[41]

According to the Tito-Tolbuhin agreement signed on November 15th, 1944 in Belgrade, the NLMY received two air divisions and one airbase with technical equipment, weapons and manpower from the Soviet side. From then until the end of the war, 350 Soviet aircraft were given to the Supreme Headquarters of the NLMY.[42] It is evident that these air-crafts and war materials received from Moscow after the partisan entrance to Belgrade were used by J. B. Tito’s Yugoslav Army for the purpose of taking control over the whole territory of Yugoslavia as well as for entering Trieste on May 1st, 1945. In April 1945 with Soviet support, forty-two storming (IL-2) and eleven hunting (Jak-3) air divisions were formed and included in the Yugoslav Army.[43] During 1944 and the first five months of 1945, the total Soviet support for the NLMY (from January 1st, 1945 transformed into the Yugoslav Army) was: 96,515 rifles; 20,528 pistols; 68,423 machine guns and submachine guns; 3,797 anti-tank’s rifles; 3,364 mortars; 170 anti-tank’s guns; 895 field’s guns; 65 tanks; 491 airplanes and 1,329 radio stations.[44] After the end of the war, all Soviet aircraft from the Bari military base was given to the Yugoslav Army which becomes the fourth largest army in Europe in manpower and military equipment. The total Soviet air support of J. B. Tito’s partisans during the whole war came to 491 aircraft.

Soviet help in training J. B. Tito’s army was also important. From autumn 1944 to February 1945, 107 Yugoslav pilots and 1104 technicians were trained in the USSR. In April 1945, 3,123 members of J. B. Tito’s Yugoslav Army were in Soviet military schools. The total number of Yugoslav pilots and technicians trained in Soviet schools during the war was 4,516.[45]

Soviet medical support sent to the NLMY was variegated and voluminous. It comprised of medical material, medicaments, and hospitals. Soviet doctors gave help to approximately 11,000 soldiers of the NLMY including those soldiers who were hospitalized in Bari.[46] In Yugoslavia, seven Soviet mobile and four surgical field hospitals were operating during the whole war.[47]

The first financial contract between the Yugoslav partisans and the Soviet Government was signed in Moscow in May 1944. J. V. Stalin allowed financial support of $10,000,000. In June 1944, J. B. Tito’s General Velimir Terzić signed a new financial contract, also in Moscow. It was an interest-free loan of $2,000,000 and 1,000 roubles. This financial aid was given by Moscow in order to help the NLMY to develop and organize its own legations, missions and to make new Yugoslav currency. In December 1944, the Soviet Union delivered a three billion new Yugoslav dinars. On January 1st, 1945, the NLMY had $1,233,480 and 300,000 roubles on its own account in Moscow’s Gosbank.[48]

The victory of the socialist revolution in Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union

The Second Session of the ACNLY held in the Bosnian town Jajce (November 29th−30th, 1943), on the territory of the Independent State of Croatia, showed overtly that socialist transformation of the Yugoslav society was the main aim of the CPY and its alleged fight against the occupiers.[49] The conclusions of this session were used by Moscow for its own political purpose in relation to its Western allies and the Yugoslav Government-in-Exile. Moscow refused to sign the Yugoslav-Soviet pact of friendship and co-operation proposed by the Yugoslav Prime Minister Božidar Purić on December 22nd, 1943 with the explanation that the Soviet Government did not see any possibility for negotiations with the Yugoslav Royal Government because of the “totally confused, unclear and unresolved situation in Yugoslavia”. However, the real reason for such a Soviet attitude toward the Yugoslav Government-in-Exile was Moscow’s intention to recognize illegal but revolutionary J. B. Tito’s Government, established in Jajce, as the only, in fact, legal Government of (post-war) Yugoslavia. For the same reason, Moscow rejected the British initiative that the USSR and the UK should pursue a common policy toward Yugoslavia. The Soviet Government recognized the changes in the political organization of the Yugoslav society in the case of communist victory during the (civil) war with a public proclamation of all decisions of the Second Session of the ACNLY via the Free Yugoslavia radio station located in Moscow and controlled by the Comintern and the Soviet Government. At that time, Ralph Stevenson, the new British ambassador at the Yugoslav royal court, observed that it was not possible to think that the Soviet Government could allow anything to be proclaimed on the radio station Free Yugoslavia that was not in accordance with the Soviet policy.[50]

British policy toward Yugoslavia during the war was to help the Yugoslav King, Petar II Karadjordjević to return to his country in order to combine the partisan and chetnik movements into a single guerrilla force against the Germans and other occupiers. The leadership of these united forces would be shared between J. B. Tito and the King. This was proposed by W. Churchill in a letter sent to J. B. Tito on February 5th, 1944.[51] This proposal J. B. Tito delivered to G. Dimitrov in order to get a piece of advice from Moscow. J. B. Tito received G. Dimitrov’s answer on February 8th, 1944 with the next Soviet decisions:

1) The Yugoslav Government-in-Exile had to be dismissed together with General D. D. Mihailović.

2) The Yugoslav Government in the country (the National Committee for Liberation of Yugoslavia) should be recognized by the British Government and other members of the Alliance as the only Yugoslav Government.

3) The Yugoslav King had to be subordinated to the laws issued by the ACNLY.

4) Cooperation with the King would be possible only if Petar II would recognize all decisions proclaimed by the ACNLY in Jajce.[52]

The Soviet Government recognized the NCLY as the only legal Yugoslav Government in May 1944 with the signing of the first financial contract with the NCLY’s mission in Moscow. It was the first international contract that was signed between the NCLY and a foreign Government. This contract was a result of the new Soviet policy toward Yugoslavia which was quite different from Moscow’s attitude toward the Yugoslav political and military situation at the beginning of the war.

Soviet diplomacy during the autumn and winter of 1941 required that J. B. Tito cooperates with D. D. Mihailović’s chetniks. General D. D. Mihailović was officially appointed to the position of Minister of Defence by the Yugoslav Royal Government in London in the winter of 1941. The reason for this Soviet policy at that time was Moscow’s wish to cooperate with both the British and the Yugoslav Governments in consideration of the difficult position of the Red Army right near the Soviet capital. As the position of the Red Army was much better in the summer and autumn of 1942, Moscow started to change its policy toward Yugoslavia by publishing J. B. Tito’s “information” about the collaboration between the chetniks and the occupiers in Yugoslavia. This “information” was sent by J. B. Tito’s partisans to the Comintern with a very political purpose. Such kinds of “information” the Soviet Government continued to receive from the Supreme Headquarters of partisan units in Yugoslavia and after the abolishment of the Comintern in the summer of 1943. During the whole war, the Soviet Government was very well informed about the military situation in Yugoslavia, particularly about the balance of power between the two domestic but ideologically and politically antagonistic guerrilla movements: D. D. Mihailović’s chetniks and J. B. Tito’s partisans. After the battles of Stalingrad and Kursk in 1943, when the USSR won two crucial victories in the war and became the supreme partner in relationships with the USA and the UK, Moscow gradually improved its relations with J. B. Tito. Officially, Moscow supported the British policy of compromise in Yugoslavia. It was a great encouragement for W. Churchill to force the Yugoslav Government-in-Exile to find a modus vivendi with J. B. Tito, but only under the condition that General D. D. Mihailović would be dismissed and that the Yugoslav Royal Government would recognize all decisions issued by the ACNLY in Jajce.[53]

The British Government was well aware that by supporting J. B. Tito its relations with the Yugoslav Government-in-Exile would be deteriorated tremendously. The British vision of the political and military situation in Yugoslavia was expressed in the Memorandum from the British Foreign Office submitted by Anthony Eden to the Cabinet on June 7th, 1944. In this document, J. B. Tito was seen as the victor in the Yugoslav civil war but quite surprisingly a leader who would pursue an independent policy (from the USSR) after the war! According to the authors of the Memorandum, Great Britain should support J. B. Tito in order to benefit later from his policy of independence from J. V. Stalin. At the same time, the Soviet Union was trying to exploit its ideological bonds with the CPY and its guerrilla movement. Surely, in the summer of 1944, London saw in its joint Yugoslav policy with Moscow the best means to reduce J. V. Stalin’s influence on the Yugoslav partisan leader. This can be confirmed by the above-mentioned British Memorandum where full support to the Yugoslav communist-led movement was proposed in order to influence J. B. Tito “to follow a line which would suit us, thus taking the wind off the Russian sails”. It was necessary if Great Britain was planning to play an active role in the Yugoslav (and the Greek) internal affairs. The new British policy regarding Yugoslavia was verified by W. Churchill who proposed to J. B. Tito during their meeting in Naples (Italy) in the summer of the same year that allied (the Anglo-American) military forces, in cooperation with the NLAY would enter Istria.

This common Soviet-British policy of compromise in Yugoslavia achieved a full success when the 1944 Tito-Šubašić Agreement was signed in the Adriatic island of Vis (at that time under the British control) on June 16th, 1944 which J. B. Tito (Croat-Slovene) negotiated in the name of the NCLY and Ivan Šubašić (Croat) in the name of the Yugoslav Government-in-Exile as its Prime Minister. This agreement was a great political victory for J. B. Tito’s partisans, supported by the Soviet Government which announced the conditions of the agreement on radio Free Yugoslavia. The 1944 Tito-Šubašić Agreement required:

1) The federal organization of future Yugoslavia.

2) Recognition of the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia (led by J. B. Tito) by the Yugoslav Royal Government in London.

3) That the NCLY and the Yugoslav Government in London would create a common Yugoslav Government.

4) That all “anti-fascist” fighting forces in Yugoslavia would be united within the NLAY.

5) That the question of the monarchy in Yugoslavia would be resolved after the war.[54]

The 1944 Tito-Šubašić Agreement gave official sanction to the ACNLY’s decisions and further consolidated the international position of the NLMY. This agreement was signed in full accordance with the Soviet policy and diplomatic tactics. Formally, the Soviet Government cooperated with the Western members of the Alliance but in reality, Moscow supported J. B. Tito in his fight to take power in Yugoslavia. The Soviet press was overwhelmingly on J. B. Tito’s side in 1944 and 1945, charging D. D. Mihailović’s chetniks with collaboration. Indirectly, Moscow charged the Yugoslav Government-in-Exile with the same collaborations with the Germans because General D. D. Mihailović was under its protection.[55]

Finally, a turning point in relations between the Soviet Government and the CPY occurred in September 1944 when J. B. Tito for the first time during the war visited Moscow (escaping from the British control on the Vis island). In three meetings with J. V. Stalin (September 21st-28th, 1944) J. B. Tito made a deal with the Soviet leader to send the Red Army across the Danube in order to support J. B. Tito’s partisans to take the Yugoslav capital before D. D. Mihailović’s chetniks would do so.[56] Likewise, Soviet troops were allowed to operate against the Germans in a limited part of the Yugoslav territory. Officially, the Soviet Government asked J. B. Tito for permission to cross the Danube River and to enter the Yugoslav territory. This Soviet “application” was interpreted by the Americans and the British as the Soviet de facto recognition of the NCLY as the legal Yugoslav Government. The NCLY’s prohibition of the British navy to use the Yugoslav seaports became a part of the 1944 Tito-Stalin Agreement. With full Soviet military support, J. B. Tito’s partisans conquered Belgrade on October 20th, 1944 and immediately introduced the revolutionary “red terror” in the city and soon in the rest of Serbia.[57] The Yugoslav Royal Government and its exponent in the country, General D. D. Mihailović lost the civil war against J. B. Tito and subsequently the Serbs to the Croats. A post-war Titoslavia was nothing else than Serbophobic Greater Croatia.[58] To conclude, the socialist revolution in Yugoslavia achieved a victory through extensive coordination between J. B. Tito’s communists and the Soviet Government.

British diplomacy tried at the last moment to save what could be saved in the Balkans by direct negotiations with the Soviet Government. For that purpose, the British Premier went to Moscow in October 1944 and had a meeting with the Soviet leader. On this occasion, J. V. Stalin and W. Churchill decided on a division of spheres of interests (in percentage) in South-East Europe: in Yugoslavia and Hungary 50:50, in Rumania 90 for the Soviets, in Bulgaria 75 for the Soviets and finally in Greece 90 for Great Britain. Without any doubt, an important consideration for London in granting such concessions to Moscow was the Soviet military penetration into the eastern portion of the Balkans and the real possibility that the Red Army would move rapidly into Central Europe. Thus, the question of Yugoslavia became once again very important in the minds of the creators of the post-war division of spheres of influence. At first sight, it looked like W. Churchill lost the battle over Yugoslavia with J. V. Stalin as immediately after the war J. B. Tito followed J. V. Stalin’s policy of incorporation of the new Yugoslavia into the Soviet bloc. Even in March 1945, W. Churchill complained in vain to J. V. Stalin that (quasi)Marshal J. B. Tito had taken power in Yugoslavia completely, and a little bit later, that Great Britain’s influence in Yugoslav affairs was reduced to less than 10 percent. However, it turned out in 1948−1949, that J. B. Tito’s Yugoslavia left J. V. Stalin’s community of “people’s democratic countries” (however, in fact being expelled from the Informbiro) and continued its existence with substantial Western help to get out of the borderlands of the Pax Sovietica Commonwealth.[59]

Conclusion

The Soviet Union had two types of relations with Yugoslavia during the Second World War:

- The first type was relations with the Yugoslav Royal Government, which was in exile and located in London. This type of relations was officially set up on the diplomatic level and carried out through legislation.

- The other type was relations with the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and its the National Liberation Movement of Yugoslavia. These relations were a secret and illegal carried out at the beginning by radio-apparatus and later by military missions.

The radio-connections between the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Government were carried out through the Comintern until its abolishment in the summer of 1943 and after that personally with G. Dimitrov. These relations were various but the most important was the Soviet material support given to the National Liberation Movement of Yugoslavia. The turning point in these relations occurred in September 1944 when J. B. Tito made a deal with J. V. Stalin in Moscow about real military support by the Red Army in order to crucially help Yugoslav partisans to take power in the country.

Approaching the question of the social revolution in Yugoslavia, the Soviet Government had a double attitude:

- During the first half of the war (till summer of 1943), Moscow mainly supported the British position that in Yugoslavia should be united both of guerrilla movements (J. B. Tito’s partisans and General D. D. Mihailović’s chetniks) into one anti-fascist alliance. During this period, the Comintern required from the Supreme Headquarters of the NLMY to give up socialist propaganda and revolutionary way of taking power.

- After the great victories of the Red Army (the Stalingrad and the Kursk Battles), however, the behavior of the Soviet Government was radically changed. From autumn of 1943, Moscow supported the new (communist) Government in Yugoslavia and pointing its “Yugoslav” policy toward revolutionary (socialist) changes in the country.

Evidently, the Yugoslav partisan movement and the spread of the revolutionary war in Yugoslavia by J. B. Tito’s NLMY were factors which in the eyes of J. V. Stalin, the Comintern and the Soviet Government should have fitted in their own objectives, mainly in a political rather than in military respect. In other words, J. B. Tito’s military efforts were used by Moscow for the Soviet political and geopolitical effects, for which they were often manipulated. The roots of such Soviet policy in Central and South-East Europe run deep, to the established Soviet foreign policy in the 1920s, implemented by the Comintern in the 1930s. This Soviet policy of domination should ensure the obedience of the communist parties in other countries and more important to exert direct Soviet influence over foreign and domestic affairs of those countries under the communist leadership by their incorporation into the Soviet political system of Pax Sovietica Commonwealth. According to J. V. Stalin’s conception of the post-war Europe, Yugoslavia should become one link of the Soviet chain composed by East-Central and South-East European socialist countries.

The chetnik movement (or the Ravna Gora’s movement or officially the Yugoslav Army in the Motherland), led by General Dragoljub Draža Mihailović,[60] was the main discord in relationships between the Soviet Government and the Yugoslav Government-in-Exile supported by the British Government (till September 1944). In this relation, the distinctive turning point occurred in December 1942 when Moscow overtly required from London to influence the Yugoslav Royal Government to change its policy toward the chetnik movement based on the false accusations by J. B. Tito’s propaganda about alleged chetnik collaborations with the occupiers.

The crucial support which during the whole war the CPY got from outside of Yugoslavia was that received from the Soviet Union what was the principal reason that the Yugoslav civil war was resolved in the favor of Serbophobic J. B. Tito’s Yugoslav communists. Finally, such Soviet policy towards J. B. Tito’s partisans ultimately benefited the USSR with fixing East-Central and South-East European borderlands of Pax Sovietica on the eastern littoral of Adriatic and eastern Alps. Consequently, “the bridge” connecting Europe and Asia (the Balkans and Asia Minor) became immediately after WWII divided between “Eastern” and “Western” political-military blocks since the major portion of the Balkans and South-East Europe left under the Soviet military, political and economic control while Asia Minor and Greece were dominated by the Western alliance. Furthermore, historical Central Europe was as well divided between the Soviets and the Westerners on East-Central Europe and West-Central Europe. At last, the political, military, and economic division of Europe on Pax Sovietica and Pax Occidentalica was sanctioned by “big three” on the Yalta and the Potsdam Conferences in 1945.

To make a final conclusion, during WWII, the allied plans were not so much concerned with the contribution made by resistance movements to the overall war effort as with the political and geopolitical importance such movements might acquire, to the detriment of the interests of some of the global Great Powers and their agreements. The civil war in Yugoslavia in 1941−1945 and the politics of the allies toward it, especially of the USSR, serve as a good illustration of the above.

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

[1] N. Popović, Jugoslovensko-sovjetski odnosi u drugom svetskom ratu (1941−1945), Beograd, 1988; B. Petranović, Srbija u drugom svetskom ratu 1939−1945, Beograd, 1992, 622−632.

[2] M. Kundera, “The Tragedy of Central Europe”, New York Review of Books, New York, 33−38.

[3] П. Симић, Тито и Срби, Књига 1 (1914−1944), Београд, 2016, 66−70.

[4] B. Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988, II, Beograd, 1988, 78−79; V. Dedijer, I. Božić, S. Ćirković, M. Ekmečić, Istorija Jugoslavije, Beograd, 1973, 478.

[5] J. B. Tito was fighting on this territory in 1914 and 1915 as the Austro-Hungarian soldier against the army of the Kingdom of Serbia.

[6] About J. B. Tito himself and his comrads, see in [J. Pirjevec, Tito i drugovi, I deo, Beograd, 2013].

[7] J. B. Tito, Sabrana djela, VII, Beograd, 1979, 41; B. Petranović, Srbija u drugom svetskom ratu 1939−1945, Beograd, 1992, 64, 161, 162, 180].

[8] M. Bosić, Partizanski pokret u Srbiji 1941. godine i emisije radio-stanice “Slobodna Jugoslavija”, NOR i revolucuja u Srbiji 1941− 1945, Beograd, 1972, 167.

[9] N. Popović, Jugoslovensko-sovjetski odnosi u drugom svetskom ratu (1941−1945), Beograd, 1988, 39−40.

[10] See, R. Petrauskas, Barbarosa: Antrasis pasaulinis karas Europoje, III, Vilnius, 2018.

[11] V. Vinaver, “Ugrožavanje Jugoslavije 1919−1932”, Vojno-istorijski glasnik, Beograd, 1968, 150.

[12] B. Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije 1918−1988, II, Beograd, 1988, 78−79.

[13] R. Bulat, (urednik), Ostrožinski Pravilnik 14. XII 1941., Historijski Arhiv u Karlovcu-Skupština Općine Vrginmost, Zagreb, 1990; V. Dedijer, I. Božić, S. Ćirković, M. Ekmečić, Istorija Jugoslavije, Beograd, 1973, 474.

[14] N. Popović, Jugoslovensko-sovjetski odnosi u drugom svetskom ratu (1941−1945), Beograd, 1988, 55.

[15] Zbornik dokumenata i podataka o Narodnooslobodilačkom ratu naroda Jugoslavije, III/1, “Borbe u Crnoj Gori 1941. god.”, Vojno-istorijski institut jugoslovenske armije, Beograd, 1950, 14.

[16] M. Zečević, Jugoslavija 1918−1992. Južnoslovenski državni san i java, Beograd, 1993, 105.

[17] E. Kardelj, Sećanja, Beograd, 1980, 25−40.

[18] E. Kardelj, Sećanja, Beograd, 1980, 50−54.

[19] Đ. Vujović, „O lijevim greškama KPJ u Crnoj Gori u prvoj godini Narodnooslobodilačkog rata“, Istorijski zapisi, Titograd, 1967, 79; B. Petranović, Srbija u drugom svetskom ratu 1939−1945, Beograd, 1992, 319−328.

[20] J. B. Tito, Sabrana djela, VIII, Beograd, 1979, 35.

[21] Zbornik dokumenata i podataka o Narodnooslobodilačkom ratu naroda Jugoslavije, I/20, Vojno-istorijski institut jugoslovenske armije, Beograd, 1965.

[22] In fact, majority of those “liberated” territories by the partisans across Yugoslavia have been simply ceded by the occupiers and especially by the Croat Nazi-fascist ustashi as a result of their collaboration with the partisans. About this phenomenon, see in [Vladislav B. Sotirović, “Anti-Serbian Collaboration between Tito’s Partisans and Pavelić’s Ustashi in World War II”, Balkan Studies, Vol. 49, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2014 (2015), 113−156].

[23] Труд, январь 12, 1942, Москва; Большевик, t. 2, Москва, 1942; Красная звезда, июнь 12, 1942, Москва; Правда, июль 19, 1942, Москва; Я. Л. Гибианский, Советский Союз и новая Югославия 1941−1947 гг., Москва, 1987, 49.

[24] B. Krizman, (urednik), Jugoslovenske vlade u izbeglištvu 1941−1943, Dokumenti, Beograd‒Zagreb, 1981, 334−335.

[25] J. Marjanović, Draža Mihailović između Britanaca i Nemaca, Beograd, 1979, 278.

[26] B. Petranović, M. Zečević, Agonija dve Jugoslavije, 1991, Beograd, 45.

[27] E. Kardelj, Sećanja, Beograd, 1980, 42−43.

[28] V. Dedijer, Interesne sfere, Beograd, 1980, 352.

[29] N. Popović, Jugoslovensko-sovjetski odnosi u drugom svetskom ratu (1941−1945), Beograd, 1988, 108.

[30] J. B. Tito, Sabrana djela, XVI, Beograd, 1979, 153.

[31] However, the civil war in Yugoslavia was already started by the partisans in West Serbia in September 1941.

[32] V. Dedijer, Interesne sfere, Beograd, 1980, 312.

[33] B. Petranović (urednik), Jugoslovenske vlade u izbeglištvu 1943−1945, Dokumenti, Beograd‒Zagreb, 1981, 291. About diplomatic activity of the Royal Yugoslav Government in London during WWII, see in [К. Николић, Владе Краљевине Југославије у Другом светском рату, Београд, 2008].

[34] N. Popović, Jugoslovensko–sovjetski odnosi u drugom svetskom ratu (1941−1945), Beograd, 1988, 111.

[35] J. B. Tito, Sabrana djela, XVII, Beograd, 1979, 54‒70.

[36] S. Vukmanović-Tempo, Borba za Balkan, Zagreb, 1981, 80−88.

[37] The Tehran Conference of 1943: The History of the First Meeting Between the Allies’ Big Three Leaders during World War II, Charles River Editors, 2016.

[38] P. Milošević, „Iščekivanje sovjetske pomoći na Durmitoru 1942“, Istorijski zapisi, Titograd, 1970, 1.

[39] Arhiv Centralnog Komiteta Komunističke Partije Jugoslavije, KPJ-Kominterna, 1944, Beograd, 12.

[40] N. Antić, S. Joksimović, M. Gutić, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska Jugoslavije, Beograd, 1982.

[41] Коммунист, “Новые документы Великой отечественной войны”, Москва, сентябрь 1979.

[42] Советские вооруженные силы в борбе за освобождение народов Югославии, Moscow, 1960, 49.

[43] Zbornik dokumenata i podataka o Narodnooslobodilačkom ratu naroda Jugoslavije, X/2, Vojno-istorijski institut jugoslovenske armije, Beograd, 1967, 412.

[44] V. Strugar, Jugoslavija 1941–1945, Beograd, 1969.

[45] Антосяк А. (редактор), “Документй о советско-югославском боевом содружестве в годы второй мировой войны”, Военно-исторический журнал, V, Moscow, 1978, 71.

[46] Советские вооруженные силы в борбе за освобождение народов Югославии, Moscow, 1960, 50; L. S. Spasić, “Jugoslovensko-sovjetske medicinske veze u Narodnooslobodilačkom ratu”, Acta historica medicinae pharmaciae, veterine, XVI-1, Beograd, 1976, 59.

[47] Н. А. Ратников, В борбе с фашизмом, о совместных боевых действиях, советских и югославских войск в годы второй мировой войны, Mосква, 1974, 105.

[48] Arhiv Centralnog Komiteta Komunističke Partije Jugoslavije, Jugoslovenske vojne misije u Sovjetskom Savezu, Beograd, 1944, 371−375.

[49] In fact, the partisans very much collaborated with the Germans, ustashi, and Albanians during the whole war [М. Самарџић, Сарадња партизана са Немцима, усташама и Албанцима, Крагујевац, 2006].

[50] D. Biber D, (urednik), Tito-Churchill: Strogo tajno, Beograd−Zagreb, 1981, 67.

[51] D. Biber D, (urednik), Tito-Churchill: Strogo tajno, Beograd−Zagreb, 1981, 83−84.

[52] M. Dželebdžić, (urednik), Dokumenti centralnih organa KPJ, NOR i revolucija (1941−1945), XV, Beograd, 1986, 449.

[53] About the Governments of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in WWII, see in [К. Николић, Владе Краљевине Југославије у Другом светском рату, Београд, 2008].

[54] J. B. Tito, Jugoslavija u borbi za nezavisnost i nesvrstanost, Sarajevo, 1977, 114−122; E. Kardelj, Sećanja, Beograd, 1980, 59−61.

[55] However, the chetniks of D. D. Mihailović have been, in fact, the only fighters against the Germans and the ustashi in WWII in Yugoslavia [М. Самарџић, Борбе четника против Немаца и усташа 1941−1945., I−II, Крагујевац, 2006].

[56] V. Strugar, Jugoslavija 1941–1945, Beograd, 1969, 265−268.

[57] Such “red terror” was done through formal instrumentalization of anti-fascism but for the real purpose of eliminating revolution enemies. This terror was only partially motivated by war, “revenge ethos”, even personal reasons, which necessarily follow almost all wars in history. Larger part of this terror represented the first phase of well-planned communist revolution, whose aim was to gradually eliminate its class and political enemies. At first, it was done by liquidations without trials, directed by secret police. Later on, formed political trials, mostly under the accusation of war crimes or some kind of collaboration, took over in Serbia and the rest of Yugoslavia [С. Цветковић, „Репресија комунистичког режима у Србији на крају Другог светског рата са освртом на европско искуство“, З. Јањетовић (уредник), 1945: Крај или нови почетак?, Београд, 2016].

[58] About J. B. Tito and Serbs, i.e his Serbophobia, see in [П. Симић, Тито и Срби, I−II, Београд, 2016/2018].

[59] J. B. Tito, Jugoslavija u borbi za nezavisnost i nesvrstanost, Sarajevo, 1977, 13.

[60] About the chetnik of Ravna Gora’s movement in WWII, see in [К. Николић, Историја Равногорског покрета, I−III, Београд, 1999].

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS