Views: 1599

Part I

The historical background of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is going back to 1917 (the Balfour Declaration) and the establishment of the British protectorate over Palestine (the Palestine Mandate) after WWI with its provision for a national home for the Jews, although formally not to be at the expense of the local inhabitants – the Palestinians. Nevertheless, it became in practice the focal problem to keep an appropriate balance between these stipulations to be acceptable to both sides – the Jews and the Palestinians.

The people and the land

Since the time of the Enlightenment followed by the Romanticism, in West Europe emerged a new trend of group identification of the people as ethnic or ethnocultural nations differently to the previous feudal trends from the Middle Ages based on religion, state’s borders or social strata’s belonging.[1] In the course of time, a new trend of people’s identification as a product of the capitalistic system of production and social order became applied across the globe following the process of capitalistic globalization.[2] As a direct consequence of such development of the group identities, the newly understood nations, especially in the areas under colonial foreign rule, started to demand their national rights but among them, the most important demand was the right to self-rule in a nation-state of their own. In other words, the ethnic or ethnic-confessional groups under foreign oppression demanded the rights of self-determination and political sovereignty.[3]

Since around 1900, both the Jews and the Arab-Palestinians became involved in the process of developing ethnonational consciousness and mobilize their nations for the sake to achieve national-political goals. However, one of the focal differences between them in regard to the creation of a nation-state of their own was that the Jews have been spread out across the world (a diaspora) since the fall of Jerusalem and Judea in the 1st century AD[4] while, in contrast, the Palestinians were concentrated in one place – Palestine. From the very end of the 19th century, a newly formed Th. Herzl’s Zionist movement had a task to identify land where the Jewish people can immigrate and settle to create their own nation-state. For Th. Herzl (1860‒1904),[5] Palestine was historically logical as an optimal land for the Jewish immigrants as it was the land of the Jewish states in the Antique.[6] It was, however, an old idea and Th. Herzl in his book-pamphlet which became the Bible of the Zionist movement was the first to analyze the conditions of the Jews in their assumed to be “native” land and calling for the establishment of a nation-state of the Jews in order to solve the Jewish Question in Europe or better to say to beat traditional European anti-Semitism and modern tendency of the Jewish assimilation. But the focal problem was to somehow convince the Europeans that the Jews had the right on this land even after 2.000 years of emigration in the diaspora.

However, what was Th. Herzel’s Eretz Yisrael in reality? For all Zionists and the majority of Jews, it was the Promised Land of milk and honey but in reality, the Promised Land was a barren, rocky and obscure Ottoman province since 1517 settled by the Muslim Arabs as a clear majority population. On this narrow strip of land of East Mediterranean, the Jews and the Arab Palestinians lived side by side at the time of the First Zionist Congress some 400.000 Arabs and some 50.000 Jews.[7] Most of those Palestinian Jews have been bigot Orthodox[8] who entirely depended on their existence on charitable offerings of different Jewish societies in Europe which have been distributed to them by the communal organizations set up mainly exactly for that purpose.

Palestine

Palestine is a historic land in the Middle East on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea between the River of Jordan and the Mediterranean seacoast. Palestine is called Holy Land by the Jews, Christians, and the Muslims because of its spiritual links with Judaism, Christianity as well as Islam.

The land experienced many changes and lordships in history followed by changes of frontiers and its political status. For each of the regional denominations, Palestine contains several sacred places. In the so-called biblical times, on the territory of Palestine, the Kingdoms of Israel and Judea existed until the Roman occupation in the 1st century AD. The final wave of Jewish expulsion to diaspora from Palestine started after the abortive uprising of Bar Kochba in 132−135. Up to the emergence of Islam, Palestine historically was controlled by the Ancient Egyptians, Assyrians, Persians, the Roman Empire, and finally by the Byzantine Empire (the East Roman Empire) alongside with the periods of the independence of the Jewish kingdoms.

The land became occupied by the Muslim Arabians in 634 AD. Since then, Palestine was populated by a majority of Arabs, although it remained a central reference point to the Jewish people in diaspora as their “Land of Israel” or Eretz Yisrael. Palestine remained under Muslim rule up to WWI, being part of the Ottoman Empire (1516−1917), when combined the Ottoman and German army became defeated by the Brits at Megiddo, except for the time during the West European Crusades from 1098 to 1197.[9] The term Palestine was used as the official political title for the land westward of the Jordan River mandated in the interwar and post-WWII period to the United Kingdom (from 1920 up to 1947).

However, after 1948, the term Palestine continues to be used, but now in order to identify rather a geographical than a political entity. It is used today particularly in the context of the struggle over the land and political rights of Palestinian Arabs displaced since Israel became established.[10]

The Jewish migrations to Palestine in 1882−1914

As a consequence of renewed pogroms in East Europe in 1881, a first wave of Jewish immigration into Palestine started in 1882 followed by another wave before WWI from 1904 to 1914.[11] The immigration of the Jewish settlers became encouraged by the 1917 Balfour Declaration, and very much intensified since May 1948 when the Zionist State of Israel was proclaimed and established.

There were historically two types of motives for the Jews to come to Eretz Yisrael (In Hebrew, the “Land of Israel”):

- The traditional motive was prayer and study, followed by death and burial in the holy soil.

- Later, since the mid-19th century, a new type of Jew being secular and in many cases idealistic began to arrive in Palestine but many of them have been driven from their native lands by anti-Semitic persecution.

In 1882 there was the first organized wave of European Jewish immigration to Palestine. Since the 1897 First World Zionist Congress in Basel, there was an inflow of European Jews into Palestine especially during the British Mandate time followed by the British allowed policy of land-buying by the Jewish Agency what was, in fact, indirect preparation for the creation of the Jewish nation-state – Israel.[12] In other words, such a policy was designed to alienate land from the Palestinians, stipulating that it could not be in the Arab hands.

Even before the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Th. Herzl tried to recruit prosperous and rich Jews (like the Rothschild family) to finance his plan of the Jewish emigration and colonization of Palestine but finally failed in his attempt. Th. Herzl decided to turn to the little men – hence his decision to convene the 1897 Basel Congress where according to his diary, he founded the Jewish state. After the congress, he did not lose the time in turning his political program into reality but at the same time, he strongly disagrees with the idea of peaceful settlement in Palestine, or according to his own words “gradual Jewish infiltration”, which, in fact, already started even before the meeting of the Zionist in Basel.

At that time, Palestine as an Ottoman province did not constitute a single political-administrative unit. The northern districts have been parts of the province of Beirut, the district of Jerusalem was under the direct authority of the central Ottoman Government in Istanbul because of the international significance of the city of Jerusalem and the town of Bethlehem as religious centers equally important for Islam, Judaism and Christianity.[13] A vast majority of the Arabs either Muslims or Christians have been living in several hundred villages in a rural environment. Concerning the town settlers of the Arab origin, two biggest of them were Jaffa and Nablus together with Jerusalem as economically the most prosperous urban settlements.[14]

Until WWI, the biggest number of Palestinian Jews was living in four urban settlements of the most important religious significance to them: Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias. They have been followers of traditional, Orthodox religious practices spending much time studying religious texts and depended on the charity of world Jewry for survival.[15] It has to be noticed that their attachment to Eretz Yisrael was much more of religion than of national character and they were not either involved in or supportive of Th. Herzl’s Zionist movement that emerged in Europe and was, in fact, brought to Palestine by the Jewish immigrants after 1897. However, most of the Jewish immigrants to Palestine after 1897 who emigrated from Europe have been of secular type of life having commitments to the secular goals to create and maintain a modern Jewish nation based on the European standards of the time and to establish an independent Jewish state – modern Israel but not to re-establish a biblical one. During the first year of WWI, a total number of the Jews in Palestine reached some 60.000 of whom some 36.000 were settlers since 1897. On the other hand, the total number of the Arab population in Palestine in 1914 was some 683.000.

The second wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine (1904−1914) had many intellectuals and middle-class Jews but the majority of those immigrants have been driven less by a vision of a new state than by the hope of having a new life, free of pogroms and persecutions.

[1] About the ethnicity, national identity and nationalism, see in [John Hutchinson, Anthony D. Smith (eds.), Nationalism, Oxford Readers, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 1994; Montserrat Guibernau, John Rex (eds.), The Ethnicity Reader: Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Migration, Malden, MA: Polity Press, 1997].

[2] About globalization, see in [Frank J. Lechner, John Boli (eds.), The Globalization Reader, Fifth Edition, Wiley-Blackwell, 2014].

[3] In the science of politics, self-determination as an idea emerged out of the 18th-century concern for freedom and the primacy of the individual will. In principle, it can be applied to any kind of group of people for whom a collective will is to be considered. However, in the next century, the right to self-determination is understood exclusively to nations but not, for instance, to the national minorities of confessional groups as such. National self-determination was the principle applied by the US’s President Woodrow Wilson to break three empires after WWI. It is included in the 1945 Charter of OUN, in the 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence of Colonial Countries and Peoples, and in the 1970 Declaration of the Principles of International Law. However, self-determination, as taken to its most vicious extremes, leads in practice to phenomena as, for instance, “ethnic cleansing” that was recently in the 1990s practiced, for example, against the Serbs in neo-Nazifascist Croatia of Dr. Franjo Tuđman or in NATO’s occupied Kosovo-Metochia after the 1998−1999 Kosovo War. In short, self-determination is the right of groups in political sciences to chose their own destiny and to govern themselves not necessary in their own independent state [Richard W. Mansbach, Kirsten L. Taylor, Introduction to Global Politics, London−New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2012, 583].

Sovereignty is the claim to have the ultimate political authority or to be subject to no higher power concerning the making and executing of political decisions. In the system of international relations (the IR), sovereignty is the claim by the state to full self-government, and the mutual recognition of claims to sovereignty is the foundation of the international community. In short, sovereignty is a status of legal autonomy that is enjoyed by states and consequently, their Governments have exclusive authority within their borders and enjoy the rights of membership of the international political community [Jeffrey Haynes, Peter Hough, Shahin Malik, Lloyd Pettiford, World Politics, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2011, 714].

[4] About the fall of Jerusalem, see in [Josephus, The Fall of Jerusalem, London, England: Penguin Books, 1999]. Josephus Flavius (born as Joseph ben Matthias, c. 37−c. 100) was a Jewish historian, Pharisee and General in the Roman army. He was a leader of the Jewish rebellion against the Roman Empire in 66 AD and was captured in 67. His life was spared when he prophesied that Vespasian would become an Emperor. Subsequently, Josephus received Roman citizenship and a pension. He is today well-known as a historian who wrote the Jewish War as an eyewitness account of the historical events leading up to the rebellion. Another of his historiographic work was Antiquities of the Jews – history since the Creation up to 66 AD.

There were two Jewish rebellions against the Roman power which inspired Jewish diaspora from Palestine: in 66−73; and in 132−135 [Џон Бордман, Џаспер Грифин, Озвин Мари (приредили), Оксфордска историја Грчке и хеленистичког света, Београд: CLIO, 1999, 541−542].

[5] He was born on May 2nd, 1860 in Pest in the Austrian Empire at that time and was given the Hebrew name Binyamin Ze’ev, along with the Hungarian Magyar Tivadar and the German Theodor. In Pest, Th. Herzl attended the Jewish parochial school, where he became acquainted with some biblical Hebrew and religious studies. In 1878, he moved to Vienna where he was studying law at the university and later working for the Ministry of Justice. In 1897, Th. Herzl published his famous book Der Judenstaat, just a year before he convened the First Zionist Congress in Basle in Switzerland. In this book in a form of a political pamphlet, he wrote that: “The idea which I have developed in this pamphlet is a very old one: it is the restoration of the Jewish state” [Extracts from Theodor Herzl’s The Jewish State, Walter Laqueur, Barry Rubin (eds.), The Israel-Arab Reader, London, 1995, 6]. According to him, the borders of Israel as Judenstaat had to be between the River of Nile in Egypt and the River of the Euphrates in Iraq.

[6] Present-day Israel (est. 1948) is the third independent state of the Jews in Palestine. The biblical Kanaan was a tiny strip of land some 130 km of length between the Jordan River, Mt. Tiber, East Mediterranean littoral, and the Gaza Strip [Giedrius Drukteinis (sudarytojas), Izraelis: Žydų valstybė, Vilnius: Sofoklis, 2017, 13].

[7] Ahron Bregman, A History of Israel, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, 7.

[8] The Orthodox Judaism is teaching that the Torah (the five books of Moses) contains all the divine revelation that the Jews as a chosen people require. In the case of Orthodox Judaism, all religious practices are strictly observed. When it is required the interpretations of Torah, references are made to the Talmud. The followers of Orthodox Judaism are practicing strict separation of women from men in the synagogues during the worshiping. In Israel, exists only an Orthodox rabbinate. While a majority of the Orthodox Jews support the Zionist movement, however, they deplore the secular origins of it and the fact that Israel is not a fully religious state. The Orthodox Jews recognize one as a Jew only in two possible cases: 1) if he/she mother is a Jew; or 2) the person undergoes an arduous process of conversion. For the Orthodox Jews, it is prohibited to cut the beard, which probably originated in a wish to be distinguished from unbelievers. About Jewish history and religion, see more in [Дејвид Џ. Голдберг, Џон Д. Рејнер, Јевреји: Историја и религија, Београд: CLIO, 2003]. The Israeli Law of Return that is governing Jewish emigration back to Israel accepts all those with a Jewish grandmother as potential citizens of Israel. Alongside with the Orthodox Judaism exist Liberal Judaism and Reform Judaism.

[9] [Geoffrey Barraclough (ed.), The Times Atlas of World History, Revised Edition, Maplewood, New Jersey: Hammond, 1986].

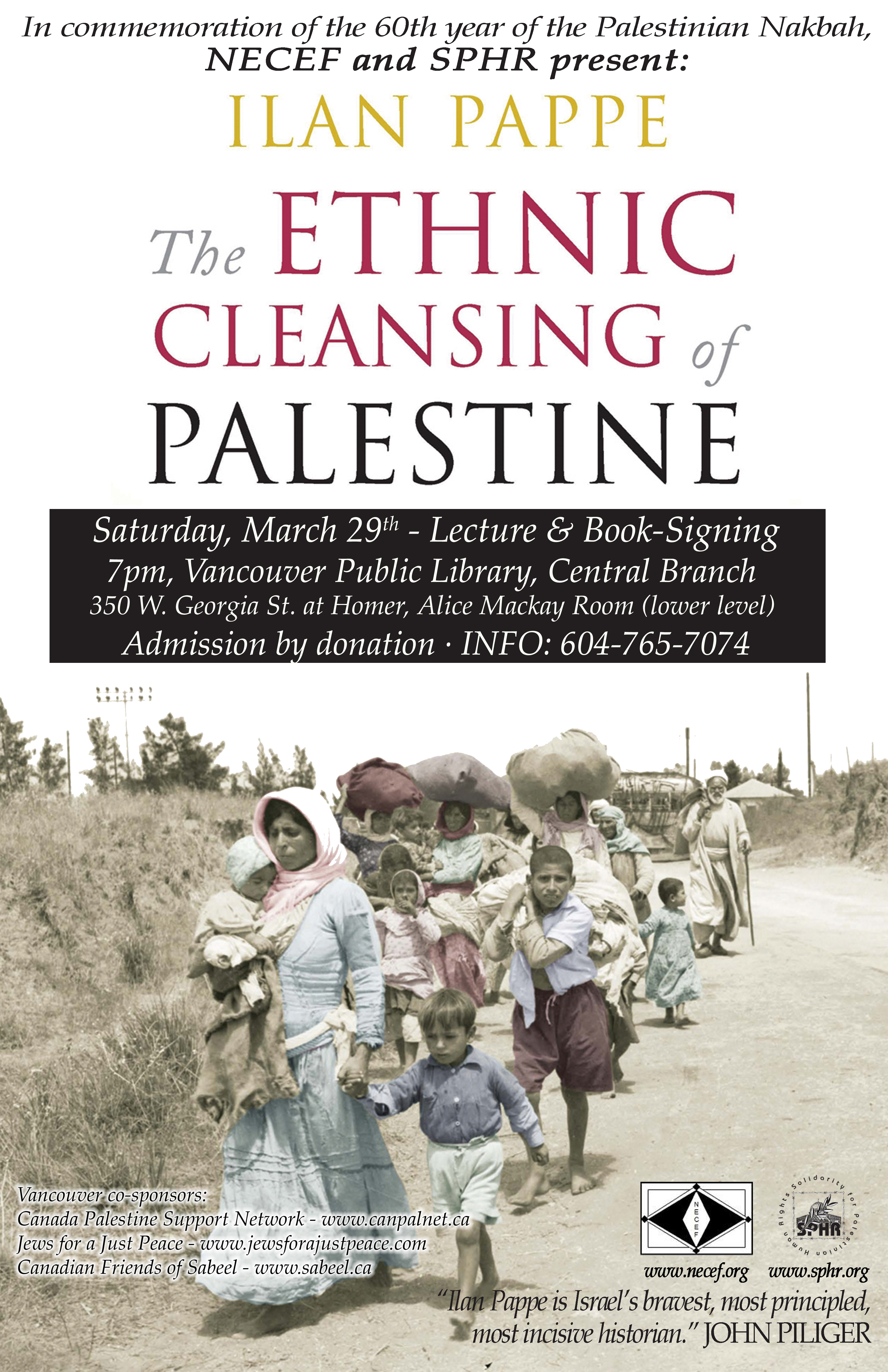

[10] About the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians by the Israeli authority, see in [Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oxford, England: Oneworld Publications, 2007]. About the general history of the Jews, see in [Дејвид Џ. Голдберг, Џон Д. Рејнер, Јевреји: Историја и религија, Београд: CLIO, 2003].

[11] The term pogrom from a very general point of view is used to describe organized massacres of Jews in the 20th century but especially during WWII in the Nazi-run concentration camps during the Holocaust.

[12] However, overwhelming of those Jewish emigrants came from Central and East Europe as well as from the Russian Empire. About the Jews in Central and East Europe, see in [Jurgita Šiaučiunaitė-Verbickienė, Larisa Lempertienė, Central and East European Jews at the Crossroads of Tradition and Modernity, Vilnius: The Centre for Studies of the Culture and History of East European Jews, 2006]. About the Jews in Russia, see in [Т. Б. Гейликман, История Евреев в России, Москва, URSS, 2015].

[13] The 1878 Ottoman census claims some 463.000 inhabitants of Jerusalem.

[14] The Ottoman population in 1884 was composed of 17.143.859 of which some 73.4% were Muslims [Reinhard Schulze, A Modern History of the Islamic World, London‒New York: I.B.Tauris Publishers, 1995, 22].

[15] Since the mid-18th century till WWII, Vilnius was known as “Jerusalem of the North” and was a center of Rabbinic Judaism and Jewish studies. Almost half of the city populations have been the Jews but according to Israeli Cohen, journalist, and writer who visited Vilnius just before the beginning of WWII, around 75% of Vilnius’ Jews were dependent on the support of charitable and philanthropic organizations or private benefactors [Israeli Cohen, Vilna, Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1943, 334]. In Jewish St. in the Old Town of Vilnius, it was established in 1892 the biggest Judaica library in the world – the Strashun Library (or the Jewish Library of Vilnius) by founder Mattityahu Strashun (1817−1885). The library was gone in 1944 as a consequence of the fight between the Germans and the Red Army. The Library collection reached 22.000 items by 1935 [Aelita Ambrulevičiūtė, Gintė Konstantinavičiūtė, Giedrė Polkaitė-Petkevičienė (compilers and authors), Houses that Talk: Everyday Life in Žydų Street in the 19th−20th, Century (up to 1940), Vilnius: Aukso žuvys, 2018, 97−100]. Vilnius up to WWII had and famous Great Synagogue. A well-known and respected Gaon of Vilnius – Elijah ben Salomon spent all of his life in Vilnius (1720−1797).

The importance of the Jewish Vilnius for the Zionist movement can be seen from the fact that the Zionist leader Th. Herzl visited Vilnius in 1903 when the Jewish representatives met him in the building of the Supreme Rabbi Board House of the Great Vilnius Synagogue [Tomas Venclova, Vilnius City Guide, Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 2018, 122].

Part II

The UK’s three promises about the Middle East during WWI

A Holy Land of Palestine became since the turn of the 20th century a battlefield of competing for territorial pretensions and political-national interests between two regional Semitic peoples – the Arab Palestinians and the Judaist Jews.[1] That was a time of a tremendous declination in power of the Ottoman Empire very much weakened after the lost 1911−1912 Libyan War against Italy followed by another lost war against the Balkan Christian Orthodox coalition in 1912−1913 when the Ottoman power was almost totally expelled from Europe.[2] At the same time, the European Great Powers, especially the UK, were strengthening their geopolitical position in the region of the Middle East including Palestine as well.

The British diplomacy in 1915 urged secretly the Ottoman governor of Mecca and Medina to lead an Arab uprising against the Ottoman authorities, which was during WWI a German political-military ally against the Entente. The Brits (Sir Henry McMahon, the British high commissioner in Egypt) promised as compensation to the Arabs if they would support the Brits in the war, London will support an idea of the creation of an independent Arab nation-state within the borders of the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, including Palestine too. The Arab uprising against the Ottoman rule was led by Faysal, a son of Husayn (Hussein) ibn ‘Ali of Hashemite house[3] and T. E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”)[4] and was successful in defeating the Ottoman authorities and, therefore, the Brits were able to take control over much of the Ottoman Middle East until the end of WWI.[5]

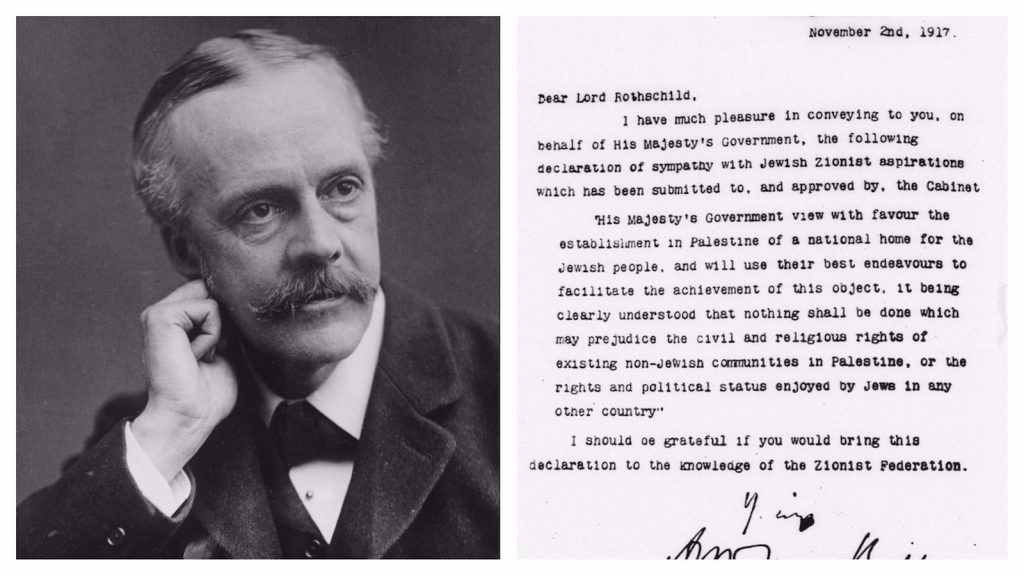

However, the Albion at the same time during the war made and other promises that went to direct conflict with the previous one about the creation of an independent Arab state on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East. On November 2nd, 1917, the British Foreign Minister Lord Arthur James Balfour signed a declaration known in history as the “Balfour Declaration” (authors were he, Walter Rothschild, and Leo Amery) by which he announced the UK’s Government’s support for the establishment of a “Jewish national home in Palestine”. That was, in fact, a letter addressed to the leading British Zionist Lord Rothschild in which the sender pledged that a Jewish home (not explicitly a nation-state) has to be created but without any prejudice to the civil or religious rights of the non-Jewish Arab people living in Palestine.[6] This statement from the Declaration, nevertheless, was a crucial contradiction in London’s diplomacy in the Middle East for the very reason as at the same time, the Albion pledged to recognize the leaders of the Arab uprising as rulers of Palestine. According to Jonathan Schneer, the Balfour Declaration laid the foundation for the origins of long and bloody Arab-Israeli conflict.[7]

The third British diplomatic promise at the time of WWI in regard to the Middle East it was a secret deal between the UK and France to divide the Ottoman Arab provinces between them and, therefore, to divide their own bilateral colonial control over the region that was finally realized after the war. This secret political deal was agreed in a form of the Sykes-Picot Agreement on January 3rd, 1916). The agreement was negotiated between the British and the French diplomats in the Middle East, Sir Mark Sykes, and Georges Picot. What they agreed, as a consequence of the Ottoman defeat in WWI, was:

- France was to be dominant in Syria with Lebanon, South Anatolia, and North Mesopotamia (Mosul).

- The UK would establish protectorates in South Mesopotamia (Baghdad and Basra), the Persian Gulf, Arabia and Hejaz, Palestine, and the valley of the River of Jordan.[8]

Therefore, according to the Sykes-Picot Agreement, Egypt would be connected with the focal British colony – the British Indian Empire while Russia will have free hands in Armenia and North Kurdistan.[9] The agreement together with the Balfour Declaration established the foundations of the Middle East’s settlement in 1920 by the League of Nations.

The 1916‒1918 Arab Uprising against the Ottoman Empire

The 1916‒1918 Arab Uprising against the Ottoman Empire

An uprising against the Ottoman rule in the region of the Middle East started in 1916. In July 1915, Husayn ibn ‘Ali, a governor of Mecca negotiated with the Brits about the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire at that time an ally of Germany against the Entente. In return, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, promised the British support for Arab independence after the war in the case of the victory of the Entente. The Arab uprising started in June 1916 when the Arab army of circa 70.000 fighters, financed by London and led by Faisal (later Faisal I), moved against the Ottoman army. The rebels succeeded to take Aqabah and to cut the Hejaz railway which was a vital strategic connection in the Arab Peninsula as connecting Damascus with Medina. This military success gave open doors to the British troops to enter Palestine and Syria. The Ottoman power in the Middle East finished on October 1st, 1918 when they lost Damascus.[10] However, the Arabs have not been granted independence after WWI as it was promised by the Brits during the war.[11]

A victory of the 1917 Balfour Declaration

After WWI, the French and the UK’s diplomats managed to convince the newly formed League of Nations,[12] in which they have been the dominant Great Powers, to grant them colonial authority (mandates)[13] over former territories of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East at that time settled by the Arabs as overwhelming majority of the population. France received a mandate over Syria but carving out Lebanon as a separate territory with a slight Christian majority. The UK got a mandate over Iraq, Jordan, and Palestine. The British colonial authority in 1921 divided the region of Jordan into two regions: 1) the Emirate of Transjordan (eastward of the River of Jordan) to be ruled by the Faysal’s house; and 2) the Palestine Mandate (westward from the River of Jordan). Nevertheless, it happened for the first time in modern history that Palestine was a unified political-administrative entity. However, the focal consequence of the British Mandate for Palestine given in 1920 was the Arab fatal dissatisfaction by the failure of London to realize in practice its promises to create an independent Arab nation-state and, therefore, the Arabs opposed both British and French Mandates as a blatant violation of the right of Arabs to self-determination – the right recognized to the Europeans during the Paris Peace Conference after WWI and based on W. Wilson’s “Fourteen Points”.

During the British and French Mandates, the political complications were more serious in Palestine in comparison to other Arab-populated territories for the very reason that London promised during WWI to support the creation of a Jewish national home (nation-state, in fact, propagated by the Zionists).

The 1917 Balfour Declaration was confirmed by the Allies, and after the war became the focal foundation for the British Mandate for Palestine given by the newly formed League of Nations in 1920. Subsequent British policy to reconcile the promises to the Zionist movement by the Balfour Declaration with Albion’s promises at the same time to the Arabs became the root of the UK’s problems during the Mandate for Palestine.[14] In one word, the 1917 Balfour Declaration directly contradicted the British promises to the Arabs in 1915 to support the creation of an independent Arab nation-state as the Declaration assumed the British commitment to support the foundation of, in fact, an independent state of the Jews in Palestine. Before the end of WWI, the British army already occupied the whole territory of Palestine and, therefore, the post-war destiny of Palestine was already decided. Subsequently, the San Remo Conference held on April 24th, 1920 just formally decided to assign the Mandate of Palestine under the umbrella of the League of Nations to the Brits. It was formally ratified by voting in the League of Nations on July 22nd, 1922 what was just confirmation of already accomplished act.[15]

As a matter of very historical fact, the Mandate document was for the Zionist Jews a pure diplomatic victory as it was the first international document in which the right of the Jews to have their own national home (state) was officially recognized, signed and ratified by the most influential Allied Great Powers who have been acting within the framework of the League of Nations as a superior international security body. In fact, what was recognized by the Mandate in 1920 was the 1917 Balfour Declaration which became incorporated into the Mandate document getting the status of a treaty.

The British military administration was soon replaced by a civil one over the British Mandate in Palestine. To which direction the mandate will go became quite clear when on the post of High Commissioner of Palestine was appointed Sir Herbert Samuel, a well-known British Jew, and Zionist. As a respected Jew, he was regarded by the Zionists as a kind of new Messiah who is going to lead the Jews back to their ancient land under the British flag through the massive Jewish immigration to Palestine followed by the purchasing of the land.[16]

[1] About the history of Palestine, see in [James Parkes, A History of Palestine from 135 A.D. to Modern Times, London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1949].

[2] See [Борислав Ратковић, Митар Ђуришић, Саво Скоко, Србија и Црна Гора у Балканским ратовима 1912−1913, Београд: БИГЗ, 1972].

[3] Husayn (Hussein) ibn ‘Ali (1853−1931) was King of the Hejaz in 1916−1925. He was a member of the Hashemite family. As an Ottoman governor of Mecca and Medina since 1908, he led in June 1916 the Arab Uprising against the Ottoman Empire proclaiming himself as King of the Hejaz and, from November of the same year, King of the Arabs. One of his sons was King of Transjordan in 1920−1951, while another was made King of Syria in 1920 and later of Iraq in 1921−1933 as Faisal I [Haifa Alanqari, The Struggle for Power in Arabia: Ibn Saud, Hussein and Great Britain, 1914−1924, Ithaca Press, 1998].

[4] Lawrence of Arabia was, in fact, Lawrence Thomas Edward (1888−1935). He was a British author and soldier. He joined the British army in 1915 in Cairo (the British Military Intelligence Department). There in Egypt, he participated in Henry McMahon’s negotiations with an Ottoman governor of Mecca and Medina, Husayn ibn ‘Ali aiming to get Arab support in the British war against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East. Lawrence Thomas Edward, as a British adviser to the Arab paramilitary forces, took an active part in the 1916−1918 Arab Uprising. He was captured and tortured before he succeeded to escape. He participated in the British occupation of Damascus in October 1918. However, he failed to secure Arab self-government for Syria and Iraq during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. In 1926, he wrote an autobiography (about his role in the Arab Uprising) under the title: Seven Pillars of Wisdom [Philip Walker, Behind the Lawrence Legend: The Forgotten Few Who Shaped the Arab Revolt, New York: Oxford University Press, 2018].

[5] About the Allied occupation of the Ottoman territories in the Middle East during the last weeks of the war, see in [Joseph von Hammer, Historija Turskog/Osmanskog/ Carstva, III, Zagreb: Ognjen Prica, 1979, 540−545].

[6] See more in [John Tiffany, A Short History of the Balfour Declaration, The Barnes Review, 2017].

[7] Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of The Arab-Israeli Conflict, New York: Random House Trade Paperback, 2012.

[8] Alfonsas Eidintas, Donatas Eidintas, Žydai, Izraelis ir palestiniečiai, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidibos institutas, 2007, 100‒101.

[9] However, the text of the agreement became publically known when a copy of it was published by the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution and Civil War causing immediately international dismay and Arab anger, as it was the British promise to support an idea of Arab independence after WWI which, basically, led to the 1916 Arab Uprising against the Ottoman authorities in the Middle East [Michael D. Berdine, Redrawing of the Middle East: Sir Mark Sykes, Imperialism and the Sykes-Picot Agreement, London‒New York: I.B.Tauris, 2018].

[10] See [David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, New York: An Owl Book Henry Holt and Company, 1989].

[11] About the Arab Uprising in 1916‒1918, see more in [David Murphy, The Arab Revolt 1916‒1918: Lawrence Sets Arabia Ablaze, Osprey Publishing, 2008].

[12] The League of Nations was an international security organization of originally 45 member-states. It was established at the Paris Peace Conference on April 24th, 1919 with the focal purpose to enable collective (international) security, arbitration of different international disputes and conflicts and to deal with the question of disarmament. The creation of the League of Nations was inspired by the failure of the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907 and the US’ President Wilson’s “Fourteen Points”. However, from the very start of its existence and diplomatic activities, the League has been crucially weakened by the refusal of an isolationist US’ Congress to ratify the membership of the USA. The first duties of the League of Nations were supervising the administrations of the French and the British Mandates in the Middle East, and the City of Danzig as well as the Saarland [George Scott, The Rise and Fall of the League of Nations, Macmillan, 1974].

[13] Mandate was introduced after WWI by the League of Nations as a form of a protectorate under which the pre-war German colonies and former Ottoman non-Turkish provinces were administered by the UK, France, and South Africa. All territories under the mandates have been classified into three categories:

- A-Mandates (Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Transjordan, and Syria). Those territories were to be prepared for a certain kind of independence through self-government.

- B-Mandates (Cameroon, Ruanda-Urundi, Togo, and Tanganyika). They have been understood not to fit for having independence and, therefore, those territories were to be administered as classic colonies.

- C-Mandates (South-West Africa and ex-Germany’s Pacific territories). They have to be administered as an integral part of the administering country. As a result, for instance, Papua New Guinea became independent only in 1975, and Namibia (former South-West Africa) even later, in 1990.

[14] Bernard Regan, The Balfour Declaration: Empire, the Mandate and Resistance in Palestine, Verso, 2017.

[15] Ahron Bregman, A History of Israel, London‒New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, 21.

[16] The biggest number of Jewish immigrants to Palestine during the mandate was from Soviet Russia as a new Bolshevik Government started in 1920 a struggle against the “Hebrew nationalism”. The rest of the immigrants arrived from Poland, Lithuania, Romania and some West European states [Giedrius Drukteinis (sudarytojas), Izraelis, žydų valstybė, Vilnius: Sofoklis, 2017, 194‒195]. See more in [Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews, London: Orion Books, 1993; Antony Polonsky, Žydai Lietuvoje, Lenkijoje ir Rusijoje, Vilnius: Versus aureus, 2015].

Part III

The British Mandate for Palestine

The focal point of the British Mandate for Palestine between two world wars was the rising tide of the Jewish immigration from Europe to Palestine followed by land buying and organizing of the Jewish settlements. Naturally, such British policy generated increasing protests and organized resistance by the Arab Palestinians of all social strata for the very reason that they feared that the massive influx of the Jews would ultimately result in the creation of a Jewish nation-state in Palestine on their land what would also result in the expulsion of the Palestinians. For that reason, the Arab Palestinians constantly have been opposing the British Mandate which thwarted their aspirations for and right to self-administration. However, in general, they opposed the massive Jewish immigration to Palestine as it could threaten their position in the country.

Nevertheless, at the same time, it was the British encouragement of the Arab patriotic nationalism in which T. E. Lawrence participated by fostering and increasing sense of the Arab identity among the Palestinians. The essence of the issue was that the Palestinians began to feel threatened, especially by very well-organized Jewish Zionist quasi-state institutions as, for example, Histadruth[1] and Haganah[2].

During the British Mandate, the first open clashes between the Arabs and the Jewish immigrants started already in 1920 continuing in the next year as well. The result of those clashes was the equal numbers of killed persons from both sides. It was obvious that the British administration of the Mandate was not able to prevent the clashes which just escalated in the coming years. The further interethnic complications in the 1920s have been provoked by the policy of the Jewish National Fund to buy large portions of land from absentee Arab Palestinian landowners with the eviction of the local Palestinians from it. As quite understandably, such displacements provoked increased tensions between the Jews and the Arabs which soon led to open violent confrontations between new settlers and old tenants.

A new moment and feature of violence between the Jews and the Palestinians started in 1928 in the holy city of Jerusalem. The violence started as a clash over their respective religious rights at the Western Wall – the Wall which is only remaining part of the Second Jewish Temple that is the holiest site in the Jewish religious tradition.[3] Above the Western Wall exists a large plateau known as the Temple Mount that was the place of previous two Jewish temples at the time of Antique.[4] Nevertheless, the same place is as well as sacred for the Muslims, who are calling it as the Noble Sanctuary. Today, the place is known according to the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock located on its top. The latter, the Dome of the Rock is of extraordinary importance for all Muslims as they believe that the Dome marks the spot from which the Prophet Mohamed ascended to heaven on a winged horse (al-Buraq), that he tethered to the Western Wall, which has the horse name in the widespread Muslim tradition.[5]

The culmination of the conflict started on August 15th, 1929 when the members of the Betar Jewish youth movement[6] organized demonstrations with raising a Zionist flag over the Western War what directly provoked the Palestinians in Jerusalem. The Arab reaction was harsh as for the reason of fearing that the Noble Sanctuary was in direct danger, the Arabs attacked the Jews in Jerusalem, Safed, and Hebron.[7] The violence lasted for a week with a result in 133 killed Jews and 115 killed Arabs with many wounded on both sides.

As a direct result of A. Hitler’s and his NSDAP rise to power on January 30th, 1933, the European Jewish immigration to Palestine drastically became increased. Of course, the new wave of Jewish immigration brought and the new waves of land buying and making new Jewish settlements on the Palestinian soil. Tensions have been intensified because the Jewish immigration to Palestine continued, as 80.000 Jews arrived from 1924 to 1931. In the years of 1932−1938, some 200.000 Jews immigrated to Palestine as a result of anti-Semitism in Europe but particularly in Nazi Germany and Austria (which became annexed to Germany).

Therefore, the Palestinian resistance to the British Mandate under which the Zionist colonization of Palestine was increasing every day was systematic and reached its peak with the Palestinian uprising from 1936 to 1939. However, the uprising was finally suppressed by force by combined actions of the British authorities, the Zionist para-military troops, and the complicity on neighbouring Arab regimes. Nevertheless, after the suppression of the uprising, the Brits have been forced to reconstruct the policy of their rule in Palestine for the very sake to keep the public order within an extremely tense interethnic environment. The Brits issued the White Paper in 1939 as an official statement of their policy of the Mandate by which both the future Jewish immigration and land buying became limited. In the same document, the Brits declaratively promised independence for the Arab Palestine. This document was regarded by the Jewish Zionists as a betrayal of the 1917 Balfour Declaration as well as anti-Semitic act taking into consideration the position of the Jews in Europe at the time who have been facing a holocaust.[8] Nevertheless, the 1939 White Papers made the end of the British good relations with the Zionists. On another hand, the defeat of the Arab uprising in 1939 followed by the exile of the eminent political leaders of the Palestinians meant in practice that they are going to be politically disorganized in the coming crucial decade in which the future of Palestine had to be decided.

The solution plan by the UN

After the end of WWII, violence between the Arabs and the Jews in Palestine did not stop even became intensified. Particular hostility occurred between the Zionist different paramilitary detachments (militias) and the British military. The British solution was to formally try to get rid of the Mandate for Palestine and, therefore, London officially requested that newly established (in 1945) United Nations (the UN or the OUN) would decide the future of this Middle East country. However, in reality, the British Government had a hope that the UN would not be able to find a solution which could be successfully implemented in the practice, and as a consequence, the global security organization would finally return Palestine back to the UK in a legal form of a UN’s trusteeship.

In order to find the “best solution”, the UN-appointed in 1946 a special committee of representatives from different countries who went to Palestine in order to investigate the real situation as a foundation for the future “best solution”. At that time, as a matter of fact, within the borders of the British Mandate for Palestine, there were 1.269.000 Arab Palestinians compared to 608.000 Jewish settlers. The Jews had in possession c. 7% out of the total land area of Palestine acquired by purchase, amounting to c. 20% of the arable land.

The results of the investigation by the UN’s representatives could be presented in two major points:

- The members of the committee disagreed about the form of a political solution of the Palestinian Question.

- Majority of the committee’s members, however, decided that the country of Palestine has to be partitioned into two parts for the sake to satisfy the national aspirations and political requirements of both sides: the Zionist Jews and the Arab Palestinians.

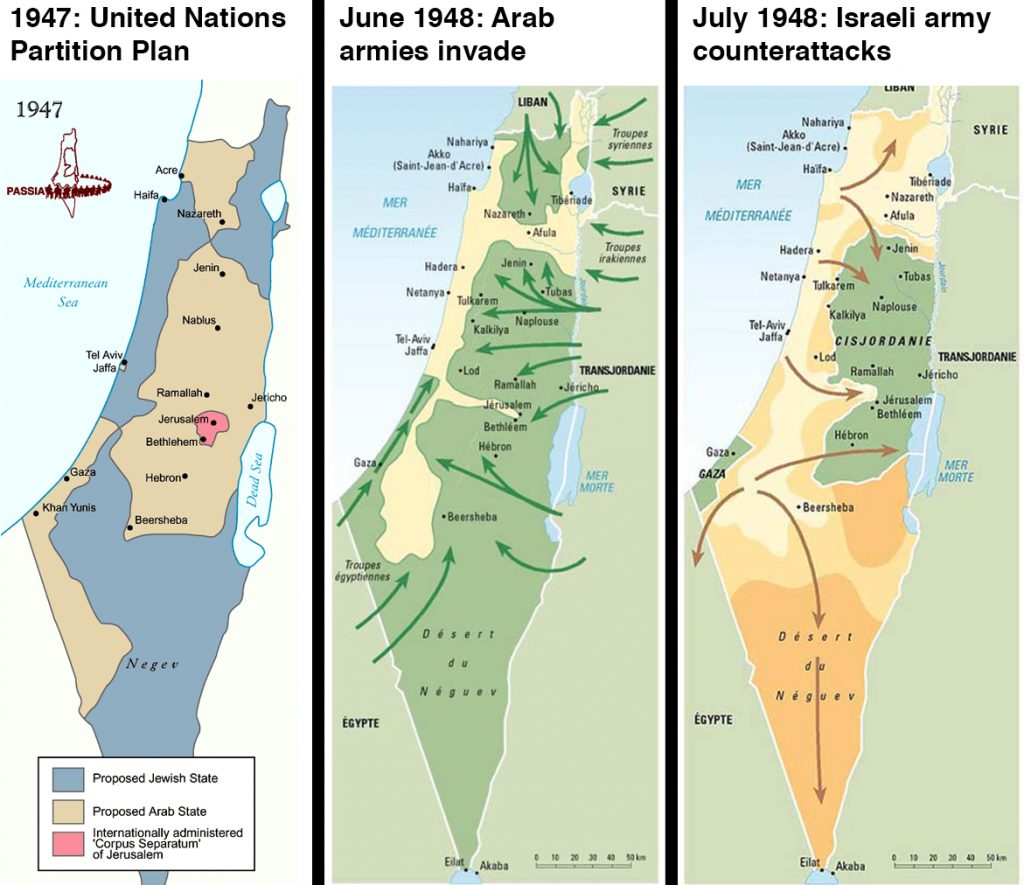

Based on the official report by the special committee, the UN General Assembly voted on November 29th, 1947 to partition the area of the British Mandate for Palestine into two independent states: 1) one Jewish, and 2) one Arab Palestinian. Nevertheless, according to this UN’s partition plan, there were three basic anomalies:

- Palestine was divided on such a way that each of those two states would have a majority of its own ethnic population. However, several Jewish settlements were included into the Arab Palestine while hundreds of thousands of the Arab Palestinians had to live within Israel.

- The territory given to Israel would be bigger (56%) compared to the Arab Palestine (43%) excluding the area of the city of Jerusalem. Israel received a bigger territory on the prediction that after the proclamation of the independence of Israel increasing numbers of the Jewish immigrants will arrive to live in their nation-state.

- The areas of the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem have to form two international zones.[9]

The consequences of the partition plan

There were several direct consequences of the 1947 UN partition plan concerning Palestine:

- The Zionist leadership officially accepted the UN partition plan but in reality, they hoped very much to expend the state’s borders of Israel on this or another way.

- The Arab Palestinians altogether with all surrounding Arabs in the region rejected to accept the UN plan and understood the voting by the UN General Assembly as an international betrayal of the justice and historical truth over Palestine. They shared a common opinion that the plan gave to the Jews too much territory which they did not deserve.

- The Arabs considered the 1947 UN partition plan and according to it the proposed nation-state of the Jews as a settler colony and claimed that the plan was voted only because the Brits had permitted extensive Zionist-Jewish colonization of Palestine against the interests of the local Arab Palestinians who have been the clear majority on the land.

- The Arabs complained in general why the question of the nation-state of the Jews has been put on the international agenda at all.

- The violence between Arab Palestinians and the Zionist Jews started immediately after the partition plan was voted by the UN General Assembly. The Palestinian military detachments have been poorly organized and equipped in comparison to the Jewish that have been much better trained, equipped, and organized regardless of the fact that the Jewish forces were smaller. As a result, up to the mid-April, the Zionist Jewish forces took control over most of the territory given to Israel by the UN and went to the offensive, occupying additional land beyond the partition borders.

Independence of Israel and the First Israeli-Arab War in 1948−1949

As it was pointed before, the United Kingdom found itself after WWII to be totally unable to resolve the growing conflict between different claims of the Palestinian Jews and Arabs and, therefore, London passed responsibility for the Mandate over to the OUN (est. 1945) which decided in 1947 on the partition of Palestine into two nation-states: one for the Jews and one for the Arab Palestinians.[10] The focal point in this concern was that the stage was set for the settlement of the issue but, instead, on Friday, May 14th, 1948, the Brits evacuated Palestine, and the Zionists under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion (the Executive Head of the World Zionist Organization and soon the first PM of the Zionist Israel) immediately announced Israel as an independent nation-state of the Jews emerging directly from the British Mandate for Palestine and fully at the expense of the founding of a Palestinian state.[11] The proclamation of Israeli independence came into force at midnight of May 15th, 1948.[12]

The Arab Palestinians, supported by other Arabs around Palestine, refused to accept Israel and in 1948−1949 they rose against a new state of Zionist Israel followed by the First Israeli-Arab War when neighbouring Arab states of Syria, Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq invaded Israel for the reason to protect Palestine from the Zionists.[13] Lebanon, as well as, declared war against Israel but did not invade the first Zionist state. Truly speaking, the neighbouring Arab states had some territorial designs on Palestine. The most intense combats happened during the first two months of the war when it looked that Israel will lose the war. However, the turning point in the war started when the arms shipments from Czechoslovakia (via Yugoslavia) reached the Zionists in Israel and, therefore, the Zionist armed detachments finally became superior.

When in 1949, the armistice was signed, the immediate results of the First Arab-Israeli War have been:

- Around 700.000 Palestinian refugees, who became either expelled on the ethnic bases or had left (temporarily) their homes in fear.

- Israel conquered additional territory from the Arab Palestine beyond its borders according to the UN partition plan in 1947.[14]

- The territory of Palestine of the British Mandate became divided into three parts, each of them has been put under different political authority. The borders between those three political entities became, in fact, the boundaries according to the 1949 armistice – the so-called “Green Line”. The Zionist State of Israel took c. 77% of the territory of Palestine. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan occupied the land of East Jerusalem[15] and the West Bank. Egypt took control over the Gaza Strip.[16]

- The Arab Palestinian nation-state designed by the UN in 1947 was not established (up today).[17]

War crimes

It is true that the exact number of the Palestinian refugees in 1947−1949 is an extremely contested issue followed with the question of the direct responsibility for their exodus. According to the testimonies, many Palestinians claimed that they have been simply physically expelled from their homes in accordance with the Zionist political design to get rid of Israel of its non-Jewish residents. However, on the other side, the official position concerning this problem by the Israeli authorities claims that those Palestinian refugees fled on orders from the Arab political and military leaders (similar happened with Kosovo’s Albanian refugees during the Kosovo War in 1998−1999). Nevertheless, there is documentary evidence that in June 1948, for instance, some 75% of the Palestinians took refuge due to the military actions done by the Jewish Zionist paramilitary troops and psychological actions for the sake to frighten the Arabs into leaving followed by many of direct expulsions. Historians recorded, for instance, that the largest single expulsion of the Palestinians during the First Arab-Israeli War happed in mid-July 1948 (around 50.000 from Lydda and Ramle). There are as well as several documented cases of massacres that led to large-scale Arab flight. For sure, the most terrible atrocity was at Dayr Yasin that was an Arab village near Jerusalem, where 125 Arab villagers were killed by the Zionist paramilitary.[18]

The 1948−1949 First Arab-Israeli War began ending in an armistice without a peace accord. As a result of the war, West Palestine came under the rule of the Zionist Israel, the Gaza Strip was put under the Egyptian authority, and East Palestine became part of neighbouring Jordan known as the West Bank.[19]

In essence, the Zionist state of Israel was and still is seen by the Arabs (and Islamic Iran) as the last example of colonialism in the Arab part of the Middle East. However, from the Jewish point of view, the creation of an independent Israel from the Mandate gave to the European Jews the real opportunity to realize their 2000 years of national aspirations to have a nation-state. Nevertheless, since May 1948 up today, the Governments of Arab states took the Palestinian Question that came to symbolize for the Arab nations of the Middle East the injustice and frustrations which have been tremendously engendered by its involvement with the West (i.e. the USA and the UK) in the 20th-century history.

[1] Histadrut was a Jewish General Federation of Labour or a Zionist trade union established in Haifa in 1920 for the very purpose to organize Jewish workers in their requirements for better pay and general better working conditions. Histadrut was the focal Jewish grass-roots movement and organization which provided great support for Mapai and the Jewish Agency. At the time when a Jewish nation-state still did not exist, the organization assumed responsibilities for its members’ health care and protection against poverty but as well as provided the most important economic services like as banking or the marketing of members’ products, etc. Histadrut continued to maintain the majority of these functions after the creation of Israel in May 1948.

[2] Haganah means defence. It was a Jewish defence paramilitary organization in Palestine established in 1920 as a secret organization for the very purpose to defend newly established Jewish settlements from the attacks by the Arabs. However, it became gradually tolerated by the authority of the British Mandate for Palestine as a kind of supplementary police force. Haganah was put under the control of the Histadrut – the General Federation of Jewish Labour. At the time of violent clashes between the Jews and the Arabs in the second half of the 1930s, Haganah acquired a General Staff and established close links with the Jewish Agency. In fact, it formed the nucleus of the army of the new Zionist state of Israel [Munya M. Mardor, et al., Haganah: A Firsthand Account of the Jewish Underground Army in Palestine, New American Library, 1966].

[3] About the West Wall, see in [Meir Ben-Dov, Mordechai Naor, Zeev Aner, The Western Wall (Hakotel), Adama Books, 1983; Leonard Everett Fisher, The Wailing Wall, Atheneum, 1989;]. The First Jewish Temple was built up seven years by Solomon [Дејвид Џ. Голдберг, Џон Д. Рејнер, Јевреји: Историја и религија, Београд: CLIO, 2003, 44]. The Second Jewish Temple existed between 516 BC and 70 AD. The construction lasted from c. 537 to 516 BC on the Temple Mount. Most probably it was built up by Zerubbabel but it was crucially restored by Herod [Michael Lustig, Herod’s Temple, CreateSpace, 2017].

[4] It has to be noticed that there is no archaeological evidence for the First Jewish Temple.

[5] Oleg Grabar, The Dome of the Rock, Belknap Press, 2006; Carter Watson, Dome of the Rock, New World City, 2018.

[6] This movement was, in fact, a kind of pre-state organization of the Revisionist Zionists.

[7] Among the killed Jews, there were 64 of them in Hebron but their Arab neighbours saved many others. Nevertheless, as a final result of the violence was that the Jewish community of Hebron ceased to exist as its surviving members left for Jerusalem.

[8] Holocaust is the term which originally denotes a victim who has been burnt completely [Jan Palmowski, A Dictionary of Contemporary World History from 1900 to the present day, Oxford−New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 277]. About the general history of the Jews including and the holocaust issue, see in [Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews, London: Orion Books Limited, 1993].

[9] See the map “UN Plan for Partition of Palestine, 29 November 1947” in [Ahron Bregman, A History of Israel, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, xii].

[10] About the British Mandate for Palestine, see in [Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs under British Mandate, London: Abacus, 2002].

[11] Ahron Bregman, A History of Israel, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, 44.

[12] The text of the Declaration of Independence, see in [Giedrius Drukteinis (sudarytojas), Izraelis, žydų valstybė, Vilnius: Sofoklis, 2017, 281‒284]. For the Arabs, Israeli independence is considered to be a catastrophe or in Arab – El Nakba [Alfonsas Eidintas, Donatas Eidintas, Žydai, Izraelis ir palestiniečiai, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas, 2007, 128].

[13] Jan Palmowski, A Dictionary of Twentieth-Century World History, Oxford‒New York, Oxford University Press, 1998, 471.

[14] See the map “Territories captured in 1948‒1949” in [Simcha Flapan, The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities, New York: Pantheon Books, 1987, 50].

[15] About the history of Jerusalem, see in [Martin Gilbert, The Routledge Historical Atlas of Jerusalem, Fourth Edition, London‒New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2008].

[16] Antoine Sfeir (eds.), The Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism, New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, 276.

[17] About the First Israeli-Arab War, see in [Ahron Bregman, A History of Israel, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, 47‒61].

[18] See [Dawid A. Assad, Palestine Rising: How I survived the 1948 Deir Yasin Massacre, USA: Xlibris Corporation, 2011].

[19] The West Bank is an area of Palestine westward of the Jordan River. According to the 1947 UN Partition Plan, the West Bank was designed as a separate Arab state alongside an independent state of Israel. The area was occupied by Jordan in 1948 during the First Israeli-Arab War and formally annexed next year. However, the annexation was recognized only by the UK and Pakistan. The West Bank was occupied by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War [Avshalom Rubin, The Limits of the Land: How the Struggle for the West Bank Shaped the Arab-Israeli Conflict, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2017; Yonah Jeremy Bob, Justice in the West Bank? The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Goes to Court, Jerusalem−New York: Gefen Publishing House Ltd., 2019].

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection, Public Domain & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS