Views: 1202

Since the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the nineties, its former constituent republics have been mired in a state of perpetual conflict.

Nowhere is this more apparent than the contested state of Kosovo.

In 1998, Albanian separatists in the Serbian province of Kosovo i Metohija began a campaign of attacks, with the express objective of creating a unified, ethnically homogenous, Greater Albanian state. Spearheaded by an organization known as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), which is widely regarded by many nations, including the United States, as a terrorist organization, ethnic Albanian militants attacked Serbian security forces, and terrorized civilians in a brutally violent campaign.

As Newton’s Third Law states, “For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” When Albanian attacks intensified, Serbian security forces rose to meet them, and the world began to take notice. Already an international pariah state following the recent conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina, Serbia, then known as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and controlled by Slobodan Milosevic, found itself on the losing end of a public relations battle. The KLA, playing the role of freedom fighters, managed to find allies in many Western nations, including NATO members. What followed was a coordinated campaign against Milosevic’s Yugoslavia, including a highly controversial 78-day bombing campaign. Following this, hostilities officially ended with the passing of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244, which mandated a withdrawal of Serbian forces from Kosovo and the institution of a multinational, United Nation-led peacekeeping force, known as the Kosovo Force (KFOR).

Image on the right: The ruins of the Church of Saint Elijah (Crkva Svetog Ilije) in Podujevo, which was destroyed by Albanian radicals during the 2004 pogrom.

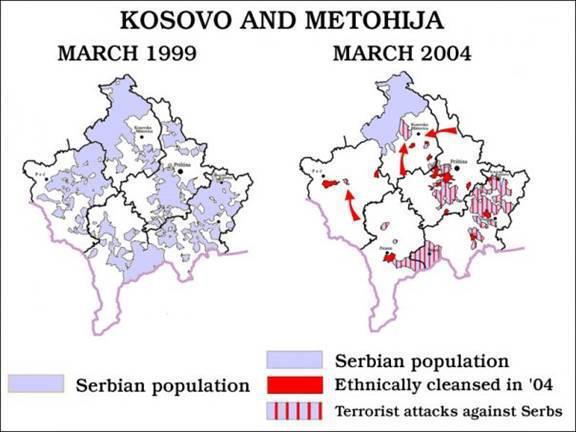

During the interim period between cessation of major hostilities and the unilateral declaration of independence in 2008, the region of Kosovo has witnessed an increase in tensions between Serbs and Albanians. One key occurrence was an anti-Serbian pogrom in 2004, which essentially amounted to an act of ethnic cleansing, according to Admiral Gregory G. Johnson, then commander of NATO forces in southern Europe. Nearly one thousand homes were destroyed, along with some of the most sacred and historic sites in Serbian Orthodoxy. Tensions became even more strained when, ten years on from the onset of hostilities in 1998, Kosovo unilaterally declared independence from Serbia, with the tacit approval of many Western nations. This move was and is seen as highly controversial in that it went against the binding UNSC Resolution 1244, which respects Serbian territorial sovereignty and integrity.

Twenty years have now passed since the opening of hostilities, and problems in Kosovo still run rampant. The economic situation is dire, with the employment rate sitting at 29.8% (while the unemployment rate was 30.5%, and the rate of inactivity was 57.2%) in 2017, according to a Labour Force Survey by the Kosovo Agency of Statistics. The region is experiencing a consistently declining population, as many people journey abroad in hopes of finding better economic prospects. Somewhat ironically, residents in Kosovo, including many Albanians, often opt for a Serbian passport, which they are entitled to under Serbian law (as Kosovo is still held as a Serbian province). They then make use of this document to make their way towards the more prosperous countries of the European Union.

Enter Hashim Thaci and Ramush Haradinaj: the former, a “President;” the latter, a “Prime Minister;” both, former commanders in the KLA; and both, accused of wartime atrocities. Facing an increasingly difficult economic situation in Kosovo, social tensions, and sliding approval ratings, both have run afoul of the other in their efforts to retain popular support, while attempting to stem the flow of emigres and maintain their grip on the region.

Thaci, formerly a key figure in the KLA, now appears to favour the image of a global leader and statesman. He cozies up to many leaders of the most powerful nations on Earth, and seeks to present an optimistic view of Kosovo as a new and rising star amongst the world’s nations. He sits opposite of Serbia’s Aleksandar Vucic in Brussels, where normalization talks between Belgrade and Pristina occur. He purveys the image of a negotiator.

On the other hand, Haradinaj appears to prefer the image of a populist hardliner, one which he has held since his days in the KLA. His bluster and swagger is vaguely reminiscent of Benito Mussolini, and given the option between offering the carrot or the stick, he always opts for the stick. Known for his violent outbursts, Haradinaj was remembered by one British soldier who liaised with him as “a psychopath,” and has been accused of killing both his rivals and enemies. Of the two, Haradinaj is said to enjoy overwhelming support and popularity in Kosovo, more so than Thaci.

Few governments in the world are completely cohesive, and differing viewpoints and priorities often cause conflict. This goes without saying for the government of the self-proclaimed Republic of Kosovo. Fights and tear gassings in parliament are common, and partisan politics are the norm. However, politics become especially tricky when the President and Prime Minister hold different perspectives. Case and point, the normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo.

Talks between Belgrade and Pristina have always been tense, with bad blood running on both sides of the table. While Aleksandar Vucic’s Serbian government is well-united behind the notion of normalizing relations with Kosovo while maintaining a policy of non-recognition, Kosovo’s strategy is somewhat more divided. Hashim Thaci appeared to have favoured an exchange of territories, likely Northern Kosovo for Serbia’s Presevo Valley, a notion which has piqued the interest of many international observers. For his part, Ramush Haradinaj has bluntly stated his opposition to this plan, responding that such an action would only destabilize the region and lead to war.

Haradinaj’s strategy at reconciliation is more populist. In November of 2018, Haradinaj stirred Albanian sentiments when he announced that Kosovo would institute a tariff on Serbian products, at a rate of 100%, and that this tariff would remain until Serbia recognized Kosovo. This tariff was likely a knee-jerk response to Serbia’s efforts to torpedo Kosovo’s latest attempt to join Interpol, as well as other organizations such as UNESCO. A slap in the face to the Central European Free Trade Agreement, of which Kosovo (through the United Nations’ Mission in Kosovo) is a signatory, Haradinaj’s latest move has been met with near-universal condemnation by world leaders, many who see it as a step backwards for stability in the Western Balkans.

The most recent and serious development to normalization between Serbia and Kosovo, as of December 2018, has been the announcement of the provisional institutions in Kosovo to transform the Kosovo Security Forces into the Kosovo Army. Seen by Serbia as the “most direct threat to peace and stability in the region,” denounced by NATO chief Jens Stoltenberg as ill-timed and regrettable, and noted by UN head António Guterres as a cause for concern, there are widespread fears that the creation of this new army will provide a mechanism which Kosovar Albanians may use to expel the remaining Serbian populace in Kosovo. In response, the Serbian government is now under pressure to consider options up to, and including, military intervention, in order to protect its endangered populace. They also asked for an urgent convening of the United Nation’s Security Council, which took place on December 17, 2018. This latest move by the Kosovar provisional authorities is yet another gross violation of UNSC Resolution 1244, and has arguably brought the Western Balkans, a veritable powder keg, to the absolute brink of war for the first time in two decades.

There is little doubt that the provisional authorities in Kosovo feel safe in their actions, for they have previously enjoyed the backing of many of the world’s most powerful nations. However, as they continue to unilaterally increase tensions with neighbouring Serbia, they may find that their list of allies is growing thin, as many nations tire of dealing with their impetuousness. Responses to their most recent moves have been overwhelmingly negative, with the European Union, Germany and the United States (among others) decrying many of these actions as unconstructive and destabilizing. Meanwhile, Serbian lobbying efforts against Kosovo are reaching a fevered pitch. The Serbian government and Foreign Ministry are working overtime to encourage nations to revaluate their positions on Kosovo’s sovereignty, and these efforts have proven successful, with twelve nations so far revoking their recognition of Kosovo.

Coordinated efforts between Serbian non-governmental organizations and actors have also proven effective in subverting Kosovo’s national aspirations. Serbian not-for-profits have assisted in delivering humanitarian aid to Serbian enclaves in Kosovo, many of whose residents live in abject poverty and suffer under a severely oppressive, Albanian dominated regime. These organizations endeavour not only to help their countrymen through material means, but also through the effective dissemination of information about the plight of the Serbian populace in Kosovo to audiences worldwide.

One such effort was the immensely successful #nokosovounesco social media campaign of 2015. Through an intense social media campaign and the circulation of a petition denouncing the Kosovar provisional authorities desire to join UNESCO while remaining unwilling to protect many medieval Serbian heritage sites, Canadian-based humanitarian organization 28. Jun and Serbian-Canadian filmmaker Boris Malagurski were successful in their objective of preventing the provisional authorities in Kosovo from obtaining membership in UNESCO.

These efforts continue to this day; building on the foundation of the #nokosovounesco campaign, a new program titled Dogodine u Prizrenu (Next Year in Prizren) was launched earlier in 2018 by 28. Jun and Mr. Malagurski, with the aim of concluding on the Orthodox New Year, January 14, 2019. The most critical component of the Dogodine u Prizrenu project is the recirculation of the earlier petition denouncing Kosovo’s membership in UNESCO which, as of the end of November, 2018, has attracted over 150,000 signatures. 28. Jun also enjoys the exclusive status as being the only NGO operating in the Western Balkans which has entered into the prestigious Special Consultative Status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council. This status enabled them to present this petition to Chairwoman Rita Izsak-Ndiaye during a session of the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Forum on Minority Issues in Geneva, on November 30, 2018. This latest move has solidified 28. Jun’s position as Serbia’s leading voice on the international stage, and has provided Serbians with another voice by which they can denounce the provisional authorities in Kosovo.

As the Serbian government and private organizations such as 28. Jun continue to curtail the efforts of the provisional authorities in Kosovo to solidify their position as a sovereign nation on the international stage, the Kosovar authorities are playing a dangerous game. In a move reminiscent of the brinkmanship observed during the escalation of the conflict between North and South Vietnam during the early 1970s, the provisional authorities in Kosovo are ratcheting up the tensions in the Western Balkans at every point They are gauging the reactions of Serbia to determine what actions they are able to get away with, despite being in contravention of many international laws and agreements. While Serbia is now reacting passively, and remains open to negotiation and dialogue, it must be known that a nation can only be pushed so far before it is forced to react in a negative manner. In order to ensure peace and stability in the Western Balkans, the provisional authorities in Kosovo must not act rashly and impulsively. Pristina must return to the bargaining table with Belgrade, lest they push the envelope too far and find out the hard way that there are very real consequences to one’s actions.

Originally published on 2018-12-19

Author: Daniel Jankovic

Source: Global Research

Origins of images: Facebook, Twitter, Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Flickr, Google, Imageinjection & Pinterest.

Read our Disclaimer/Legal Statement!

Donate to Support Us

We would like to ask you to consider a small donation to help our team keep working. We accept no advertising and rely only on you, our readers, to keep us digging the truth on history, global politics and international relations.

[wpedon id=”4696″ align=”left”]