Views: 934

Preface

It is the 30th anniversary of the first post-WWII democratic elections in Serbia and the rest of the ex-Yugoslavia.

My aim in this article is to elaborate on the feature of the multi-party elections in Serbia in 1990 and to give an answer to the crucial question why did Slobodan Miloshevic with his SPS party win? After the investigation of the case we found that critical reasons for Miloshevic’s/SPS absolute electoral parliamentary and presidential victory in 1990 have been: 1) The countryside and small urban settlements voted for SPS due to the informative blockade; 2) Old population voted for SPS; 3) All minorities, except Hungarians, voted for SPS as a lesser nationalistic option than SPO; 4) The biggest minority – Albanians (10%) boycotted the elections; 5) All Kosovo Serbs voted for SPS; and 6) The whole electoral procedure was under SPS control.

Nature of Political System in Serbia in the early 1990s

Many foreign political scientists argue that the political (and electoral) system in Serbia during the process of Yugoslavia’s dissolution could be classified as „authoritarian“. This system is characterized by the limited political pluralism, aggressive populist rhetoric, the concentration of power by the party leader and clique around him and their ability to manipulate the electorate.[1] Some researchers outline the continuity of such personal and unpredictable nature of single-man political power in Serbia during the whole twentieth century and ground this system to the traditional Balkan „pater familias“ (father of the family) model of the ruling rural large family society („zadruga“)[2].

The tendencies to bring the familial power of Slobodan Miloshevic’s family over the state were transparent in Serbia’s political system in the early 1990s. The leader of the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS) S. Miloshevic and his wife Mirjana Markovic, the leader of Yugoslav United Left party, ultimately supervised the state political life, army, police and economy. Their kinship expanded to mass media contributing to the control and manipulation of the information channels and civil initiatives, which lost а great degree of independence and critical voice to the regime. In such a system the personal service to the party leader and relationships with his family guaranteed success and prosperity[3]. As a result, Serbia failed to make the political leap from totalitarianism to pluralism and left behind the successful democratic transition in Eastern Europe[4].

Serbia’s state politics heavily relied on the nationalistic rhetoric that merged together political unity and national claims[5]. This theoretical Ernest Gellner’s framework has had its practical interpretations by both SPS leadership, on the one hand, and some leaders of oppositional parties such as the Serbian Radical Party lead by Vojislav Sheshelj and movements such as Serbian Revival Movement lead by Vuk Drashkovic, on the other. They claimed that ethnographic borders should be expanded to the national-state borders or another way around that the state should enlarge its borders in order to include both the territories settled by dispersed Serbs and lands that historically belonged to the „national“ state[6]. By combining these two ethnic and historic rights, Serbian nationalists (like many others in their own national cases) required the creation of United Serbia from the Krayina region in Croatia (according to ethnic rights) to Kosovo in Serbia (according to historic rights). In this way, both political blocks in position and opposition gained popularity among Serbian citizens but lost political and financial support from the western democracies. Nationalistic rhetoric by oppositional Serbian Radical Party and Serbian Revival Movement was even more radical than S. Miloshevic’s political discourse and thus discredited any other oppositional units such as Democratic Party, Serbian Liberal Party and other political forces that called for democratic transition in Serbia. Western European countries and the USA maintained distance to the events in March 1991 and did not provide any support to democratic parties which succeeded to organize a mass demonstration against S. Miloshevic’s growing political regime but failed to defeat it.

By developing discourse of “national mobilization” and patriotism to fight for national interests, Miloshevic succeeded to gain political power in 1987−1989 and maintain it for the whole decade from 1990 to 2000[7]. As the chapter below will suggest Miloshevic effectively manipulated certain “democratic” mechanisms of the pluralistic political-electoral system in Serbia and at the same time established his own absolute power by gaining major support from the Serbian population. The oppositional political forces experienced a very difficult task to contest Miloshevic’s iconic image and obtain support for political-social reform and civic society values in Serbia. Thus, nationalistic rhetoric was explored by oppositional parties as well to appeal to the electorate and win support.

Multi-Party System: Limited Development of Democracy

In 1990 Yugoslavia followed the model of political transition from a one-party regime to a multi-party democratic system that was similar to the other Central and Eastern European countries. For the first time after the Second World War, both presidential and parliamentary elections were organized in a democratic way when newly established political parties and politicians could participate in the elections. The adopted Law on Political Organizations (July 19th, 1990) allowed setting up various political associations. In Serbia, many political forces demanded to draft a new democratic constitution and develop an open democratic society. Political agenda of majority political organizations openly rejected communist and socialist regimes and supported human rights, democracy, and market economy. However, the results of the parliamentary and presidential elections in other republics of Yugoslavia made a negative impact on democratic forces in Serbia and to a certain extent reinforced the position of the former Communist Party. During the period from May till November 1990, elections were held in four Republics of Yugoslavia, namely, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Macedonia. By applying nationalistic rhetoric newly elected parliaments and presidents of these four republics expressed their claims for independent ethnic states and separation from Yugoslavia. The rhetoric of ethnic nationalism became developed into the driving force for success in the multi-party system to gain and maintain political power.

In Serbia, the elections were scheduled in December when the broad spectrum of the most influential political forces from the former Communist party to the democratic bloc and even new Royalist bloc could participate. By observing the electorate behavior of nationalistic parties in other four republics of Yugoslavia, Serbia’s former Communist Party (i.e., League of Communists of Serbia), renamed to Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS) and led by Slobodan Miloshevic, mobilized financial and information resources and adopted aggressive nationalistic rhetoric in the electoral campaign. SPS addressed the danger of growing nationalism in other Yugoslav republics and positioned itself as the savior of Serbian national interests.[8] Being the successor of the Communist Party, SPS appropriated all rights and material wealth, political infrastructure and organizational networks of the former Communist Party. Though a significant number of the membership was lost, SPS had mostly professional cadre in comparison to other parties.

Maintaining the political power, SPS succeeded to adopt the legal acts to help their party in winning the parliamentary and presidential elections in December. The law on plurality (majoritarian) voting system allowed any party to participate in the elections but de facto restricted them in getting the majority of seats in the parliament. Oppositely to the proportional representation system that provides the close match between the percentages of votes and seats, the plurality voting system advantaged the party which collected the single majority votes by allowing this party to obtain the absolute majority of seats in the parliament. As a result, on December 9th elections SPS got the majority seats in the parliament.

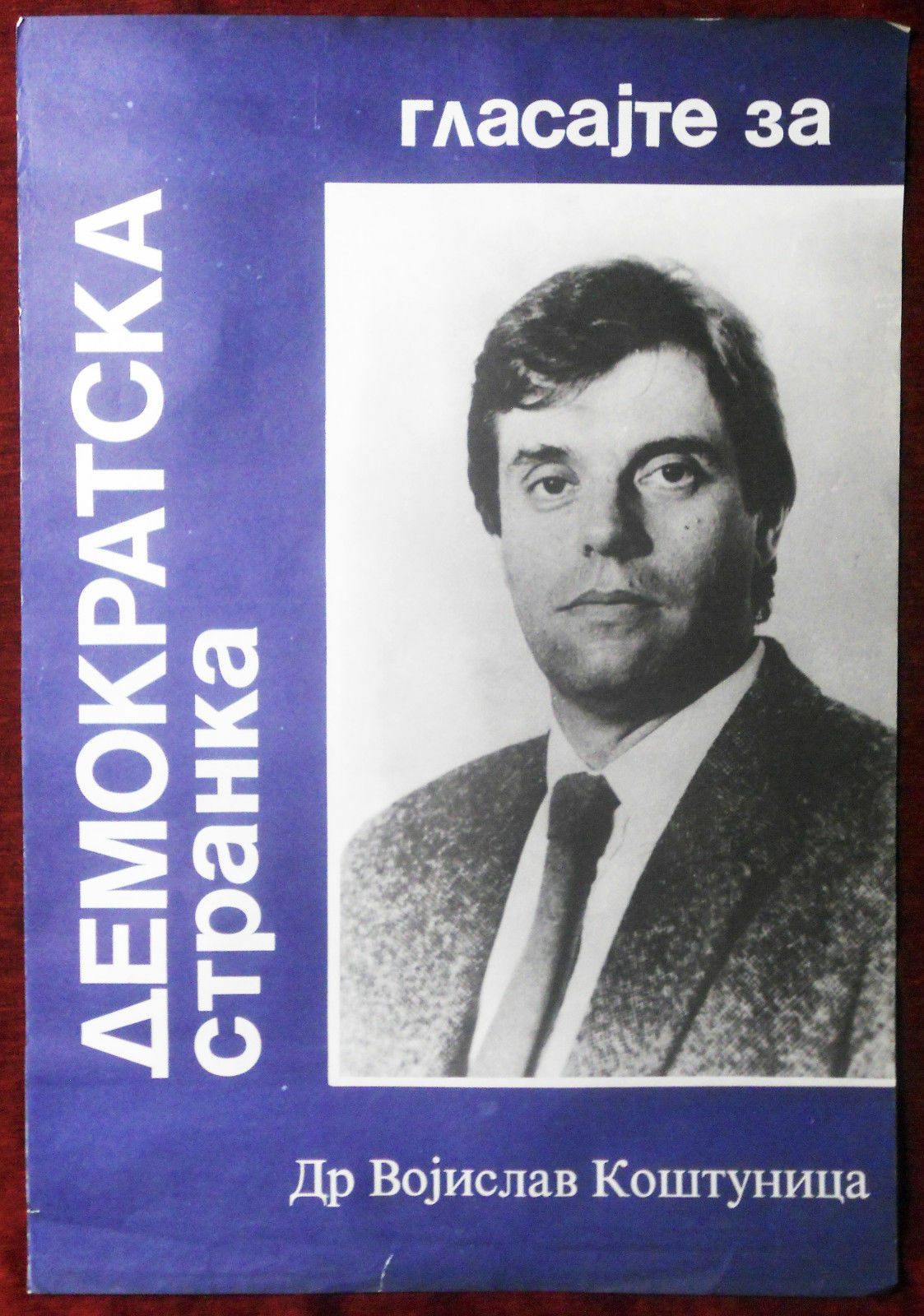

The oppositional parties in Serbia, however, left behind of SPS in terms of political and organizational infrastructure. Regardless on these weaknesses, two main oppositional organizations, namely Democratic Party (Demokratska stranka – DS) lead by Prof. Dragoljub Micunovic, and the royalist Serbian Revival Movement (Srpski pokret obnove – SPO) led by at that time charismatic populist leader – the writer Vuk Drashkovic, had the potential staff and supporters to participate in the political life of Serbia.

Democratic Party (DS) was formed by Belgrade intellectuals (many of them former political dissidents who protested against the last Yugoslav Constitution of 1974 according to which Serbia was divided into three territorial-political units (Vojvodina, Kosovo and the rest of Serbia). The precursor of DS was the Committee for Human Protection illegally worked in Titoist Yugoslavia in the 1970s and 1980s as in fact the only opposition organization to totalitarian regime run by Josip Broz Tito. On November 11th, 1989 a group of 13 intellectuals publicly proclaimed the organizational establishment of DS that became the first opposition party in Serbia. The most distinguished signatories of the act that created DS have been later its leaders: Dr. Dragoljub Micunovic, Dr. Kosta Chavoshki, Dr. Vojislav Koshtunica, and Dr. Zoran Djindjic. In early 1990, the party was united to the assembly of many small parties and liberal movements. Even the leadership was composed of the board council, where several leaders in consensus made the decisions[9]. The main focus of the party program was concentrated on a clear program of economic and political reforms rather than nationalism and exclusive Serbian national traditions. The political agenda of the Democratic Party was based on traditional European liberalism of civic society. They saw future Yugoslavia as democratic federation composed by all of the nations who by their own will expressed common state and democratic political systems. Regardless of very sharp critics of communism, the party had an unclear national program and weak populist leadership contrary to SPO.

The other influential oppositional party, namely, the Serbian Revival Movement (SPO), focused primarily its political program on solving Serbian national question according to the dominant framework of German Romanticism from the 19th century that claimed the model of one nation – one state[10]. The leader of the party, the writer Vuk Drashkovic, previously was affiliated to the nationalistic Serbian National Defense organization (Srpska narodna obnova – SNO) and proposed to form the special Serbian paramilitary forces and fight for „Greater Serbia“ in order to protect all the territories settled by Serbs. This first of all addressed Serbs in Kosovo allowing questioning large-scale autonomy of Kosovo within Serbia and even proposing to cancel such its status. The new Drashkovic’s party – SPO – based its program on promises to introduce democracy and rule of law in Serbia, a revival of genuine cultural traditions of the Serbs and restoration of the powerful influence of the Serbian Orthodox Church as it used to have in the pre-WWII times. Due to these populist ideas, the movement rapidly got huge mass popularity and expected to win the upcoming parliamentary elections and maybe presidential ones as well. For this purpose, SPO organized an extensive electoral campaign by organizing the oppositional meetings across and outside Serbia. Economic issues were secondary than political, however, clearly expressed suggesting the tendencies to develop a market economy, private possession over the tools of production and private business initiatives. Oppositely to the other big political organizations, SPO had a very specific strategy in its political-national program, notably, to restore the monarchy by crowning the Yugoslav Prince Alexander II Karadjordjevic who has been the legal successor of pre-war Yugoslav royal dynasty of Serbian origin. Before the December elections, SPO had about 700.000 supporters and 500 offices in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Croatia.

The other political organizations were significantly smaller, without broad social and strong financial support existing on the margin of political life.

The Elections of 1990

The independent public opinion research on possible results of elections suggested that in September 1990 the most popular were three parties and their leaders. The highest numbers of votes could expect Miloshevic’s SPS (26%), the other two most supported were Dragoljub Micunovic’s DS (13%) and Drashkovic’s SPO (11%). However, almost half of the electorate (45%) did not have a clear opinion on which political force to favor. In the following months, the electoral support to SPS increased due to its position in power, control of media allowing minimizing the time for opponents on TV and radio for the electoral campaign and successful Yugoslav army operations against Croatian governmental forces. S. Miloshevic’s popularity grew up and left behind SPO and DS parties and their leadership.

The significant result of S. Miloshevic’s party’s growing popularity was the total control of informational channels, such as national Radio and TV of Serbia and daily newspaper „Politika“. The events of June 13th, 1990 showed that the ruling SPS rejected any dialogue with the opposition and practically manipulated the oppositional democratic forces to win the votes of the electorate. On June 13th, 1990 some oppositional democratic forces united under the Associated Opposition of Serbia called for public protest against SPS control over national media. More than 70,000 people of the peaceful demonstration were dispersed. Later in autumn the same Associate Opposition of Serbia again organized mass protests in Belgrade demanding fair conditions for each political force in the electoral campaign including 90 days of the campaign, two hours of television time per day during the election campaign and the round-table talks. Though the opposition demanded to agree with the leadership and ruling forces of SPS, these demands were not taken into consideration by SPS who continued their informational control over the electorate campaign.[11] Nevertheless, the government of Serbia granted few minor concessions to the opposition allowing the latter for access to the television during the electoral campaign and simplifying the registration for the candidates of president elections according to the Law on Election issued on September 28th, 1990. However, SPS did everything to stop the public appearance of opposition on TV. The scheduled round-table talks among position and opposition broke down due to SPS leadership’s political ambitions. For the SPS leaders, the round-table discussions became the political platform to spread their virtues and achievements rather than a real exchange of opinions. As Vojislav Koshtunica (DS) argued, most East European countries provided fair conditions for all parties to address the voters and present the party’s agenda, but in Serbia, a few concessions rather than real negotiations and discussions were preferred[12].

Absence of the united oppositional block before the elections also contributed to the victory of SPS in the parliamentary and presidential elections. By debating the law on elections that introduced a “majoritarian” system, the opposition disagreed on whether to boycott the elections as non-fair for oppositional parties or participate and win though small but important voices in the parliament. Vuk Drashkovic and his SPO strongly argued that the united boycott of the elections would discredit the legitimacy of the new „democratic“ post-elections regime. Meanwhile, Zoran Djindjic, one of the leading figures at DS, argued that the opposition should take the opportunity in the election campaign in order to record the illegal actions of the ruling SPS and inform the nation of them[13]. Due to significant Djindjic’s political influence, DS decided to participate in the December 9th elections regardless of the resistance of majority DS leaders. The oppositional SPO party publicly declared their strong position to boycott the elections but had to change their tactics and join the elections at the last minute. SPO leadership had finally realized the plans of DS and other democratic forces to involve SPO in the elections, on the one hand, and the possible future of SPO to be marginal in state policies, on the other. Though SPO faced the problems of limited time and resources, their electoral campaign was based on optimistic views that Serbian citizens will not support SPS as the former Communist Party. Relying on the experience of Eastern and Central Europe SPO and its leadership believed that socialism will be swept out as a historically failed ideology and policy in this region as well. However, they did not properly evaluate the seriousness of SPS campaign, their control of media and strong organizational infrastructure.

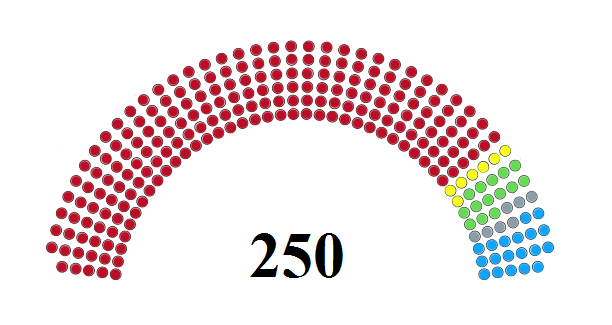

The elections for the National Assembly (Narodna skupština) on December 9th, 1990 did not bring unexpected results. The majority of the voters (46%) gave their support to SPS. Due to the electoral system, that was structured by SPS (and finally recognized by the opposition with believing that such system will bring final electoral victory exactly to them but not to SPS), the party won 194 seats (77,6%) in the parliament out of 250. SPO with 15,8% got only 19 seats (7,6%), the Democratic Alliance of Vojvodina’s Hungarians (Demokratski savez vojvođanskih Mađara – DSVM), benefiting from the territorial concentration of their supporters, gained 7 seats (3,2%) with 2,6% of the votes, DS 7 seats (obtained 7,6% of votes). The rest of 13 political organizations, elected to the Parliament, won between 1 and 2 seats[14].

The results of the elections to the National Assembly had shown a twofold phenomenon. Firstly, a number of smaller parties and independent units did gain representatives in the National Assembly. Secondly, the gained voices of the oppositional parties were too small to compose a strong opposition. The elections to the National Assembly demonstrated the limits of democracy in Serbia when previous party system attributes were modified to introduce democratic elections and continue to control and maintain the real power by the same ruling (former Communist, currently SPS) party.

Similar tendencies of limited democracy were functioning in the presidential electoral campaign. The Serbian constitution (September 28th, 1990) introduced the system of a presidential republic in Serbia that was used by S. Miloshevic in his electoral campaign as the main advantage against his opponent-candidates and which finally allowed him to stay in power for the next decade. Having a wide scope of prerogatives of political power the presidency became, in fact, the crucial political institution. During two months of the electoral campaign, the presidential power was sophisticatedly wrapped into nationalistic clothes by mass-media. American sociologist Eric D. Gordy calls political system in Serbia in the 1990s as nationalist authoritarianism taking primarily into consideration a strong presidential position which was surviving in power due to nationalistic rhetoric.[15] There were two reasons for the strong presidential element in the constitution that was adopted exactly on the first day of the electoral campaign and thus became a part of it: 1) to provide an advanced position of SPS candidate to the post of Serbia’s president in comparison with opposition candidates; and 2) Miloshevic believed that his future election as president was already assured and that therefore he needed to safeguard his position against control by the parliament which might be dominated by united opposition bloc.[16] The new constitution of Serbia was promulgated on September 28th, and on the same day, multi-party elections were announced for the December 9th, 1990.[17]

For the post of Serbia’s President, a competition was between 32 candidates. The most chances to win had SPS leader Slobodan Miloshevic, SPO leader Vuk Drashkovic and Belgrade University professor Ivan Djuric. During the presidential electoral campaign, the SPS candidate – an actual Serbia’s president, Slobodan Miloshevic, had the most chances to win mainly due to privileged position in state media and combined rhetoric of modest nationalism and necessary reforms of social and economic life in Serbia. The tactics of avoiding rhetorics of aggressive nationalism on the public scene retained him popularity from the years 1987–1989. Formally advocating the values of civic society and propagating Serbia as the motherland of all of her citizens Miloshevic skilfully targeted his campaign towards ethnic minorities in Serbia.

The presidential election campaign of Vuk Drashkovic was mainly shaped within the framework of radical ethnic patriotic nationalism for national mobilization for defense of Serbian interests in Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Kosovo-Metochia.[18] His democratic nationalism combined with a call to change illegitimate Miloshevic’s power structure in Serbia succeeded to mobilize a huge number of ethnic Serbs before the elections, but on the other hand, it showed the failure to cooperate effectively with other ethnic communities.

The third most prominent presidential candidate, Ivan Djuric, was a scientist, Byzantologist, professor at Belgrade University, humanist and one of the most critical democratic speakers against either Miloshevic’s or Drashkovic’s nationalistic policies, but not having any experience in the politics. He was a candidate of pro-western Serbia’s Reformists – a political association fighting for democratic Serbia as a member of the European Community/Union. Differently to Miloshevic and Drashkovic, Djuric enjoyed great respect by the majority of western governments and diplomats. However, on the other hand, he had lesser chances to obtain mass support by the electorate, necessary to win presidential elections, as he rejected nationalism from his electoral program.

Finally, the results of the presidential elections in Serbia showed more or less expected outcomes of the pre-electoral campaigns: the most votes won Slobodan Miloshevic (63%) followed by Vuk Drashkovic (only 16,4%).[19] The only other candidate who succeeded to obtain a significant proportion of the votes was Ivan Djuric (5,52% or more than 300.000 votes)[20].

Why SPS won?

The reasons for SPS triumph can be located in a number of structural and institutional advantages that they enjoyed over the opposition parties. The SPS had inherited from the Communist Party of Serbia (a real name the League of Communists of Serbia – LCS), largely intact, a structure of branches and membership extending across the whole country. After the Law of Political Organizations passed on July 19th, 1990 SPS succeeded to retain the biggest number of former 400,000 LCS members. The SPS presence in the factories by establishing its own “workplaces” served as an expression of the party’s dominance of economic as well as political life. The opposition parties, by contrast, had to create their new party local and national networks from the beginning and over a short time. As a result, by the time polling took place on December 9th, 1990, many of the opposition parties had organizational party structure developed only in a few specific locations – mainly big urban settlements. The opposition parties also faced severe financial problems which seriously inhibited their capacity to effectively conduct their election campaign. The SPS also enjoyed further logistical superiority over the opposition through their total monopoly of power in local and central governments, in the run-up to and during the election campaign.

The greatest institutional advantage held by the SPS, however, was their almost total control over the electronic media. The opposition had, before the election campaign, won concessions regarding access to the media but the presentation of the party programs was within a uniform length and did not distinguish between those with negligible support and those, such as SPO and DS, who had a substantial following. By contrast, support for SPS permeated the entire news output of the RTS, main Serbia’s TV network covering the whole country. The broadcasting range of neutral and more balanced TV networks, like Belgrade Studio B, however, did not reach beyond the greater Belgrade area leaving huge parts of inner Serbia’s hinterland, and particularly the rural areas depended on the state-controlled media. Finally, during the election campaign, even the Yugoslav People’s Army was prepared to defend SPS staying in power. That was announced by top army officials’ statements (like of General Veljko Kadijevic) in a form to warn Serbia’s voters of the danger that civil war might break out should the opposition be victorious.

The tone of Miloshevic’s and SPS electoral campaigns contributed greatly to their electoral victory in 1990 followed by an establishment of the post-electoral one-party dominated National Assembly and state’s authoritarian one-man leadership (like in Tudjman’s HDZ Croatia). The SPS campaign emphasized “positive” values of Serbia and Serbian citizens such as economic development and prosperity based on domestic natural and human resources. Surprisingly, at the heyday of the campaign the nationalism, which brought Miloshevic to power in 1987, by contrast, played a distinctly subsidiary role; contrary to the SPO campaign. That was the main reason why SPS succeeded to win a majority of Serbia’s minority votes including even and some small numbers from Albanian electorate (while the overwhelming majority of Kosovo Albanian electorate boycotted the elections). Miloshevic opted not for insulting opposition leaders but rather for ignoring them on the public scene what left to the electorate an impression of opposition as a politically irrelevant part of the society. Oppositely to him, radical and fiery nationalistic rhetoric of Vuk Drashkovic and SPO alienated many non-ethnic Serbs and the majority of aged electorate for whom SPO leader was more like rock and roll singer or the Chetnik[21] propagator (with long hear and bear) rather than a serious politician. The clashes by SPO supporters and local Serbia’s Muslims in Rashka region after nationalistic speeches by SPO leaders were sophisticatedly used by Miloshevic’s propaganda machinery. However, probably the critical reason why opposition did not gain stronger electoral support among ethnic Serbs was the fact that its leadership openly propagated pro-western orientation of Serbia’s political post-totalitarian course at the moment when the European Community led by traditional Serbian enemy – (united) Germany advocated and supported the dissolution of Yugoslavia without living place for united Serbian state. Besides, propagating a liquidation of “Albanian independent state of Kosovo within Serbia” by SPS gave them great popularity as real defenders of Serbian national pride.

Finally, beyond the fact that SPS controlled all key features of the political life during the election period, it has to be also mentioned that their ideological message found an appropriate soil to be absorbed by a big part of a conservative section of Serbian society. The SPS had been able to revise their image presenting themselves as following a policy of reform, but without the systematic change (using the slogan “Sa nama nema neizvesnosti/No uncertainty with us”), and therefore disruptive upheaval, advocated by the opposition. The SPS was also able to combine its ideological formula with the promise of actual material gain (for instance, a living standard like in Sweden). The rural population was attracted by the SPS policy of the restitution of land confiscated from the peasantry after WWII (in 1946 and 1953).[22] In general, the Socialist voters have been mainly those whose degree of poverty within the socialist system was such that they feared any radical change (advocated by the opposition) would rob them of what little they had. This support group included not only Serbia’s significant rural population, but also workers from heavy industry factories on the suburban parts of the large towns (like Rakovica in Belgrade), low-level officials from the civil service, and old-age pensioners. It is more clear if we know that Serbia’s working classes were the product of the processes of mass urbanization and industrialization under socialism who largely continued to give their support to the successor of the political party which was their progenitor. The results of electoral policies in Serbia in 1990 showed not only a town/countryside division but also a strong regional differentiation. Support to SPS was particularly strong in the poverty-stricken areas of the south-east (Nish, Leskovac, Vranje) and was much weaker in the more affluent north. The opposition parties were also, in contrast to SPS, strongest in northern and western Serbia. For higher educated and materially better-situated population the prospect of change was more likely to be a source of hope than fear. At the time of Serbia’s first multi-party elections, however, this group remained a minority within the country’s electorate.

Conclusions

This article aims to investigate the nature and results of electoral politics in Serbia during the period of the beginning of the violent dissolution of ex-Yugoslavia and the first multi-party elections in 1990. Two levels of elections are taken into consideration: presidential and parliamentary. Oppositely to other Central and East European states, Serbia at the beginning of the 1990s has not been involved in the process of political transformation from totalitarian one-party elections controlled system into democratic multi-party free elections model.

„Transition without transition“ – that was a formula implied by the ruling party to the political life of Serbia during the process of Yugoslavia’s dissolution. Political life has seen the adoption of some of the formal attributes of democracy but without the stable institutional support to that system. The ruling Socialist Party of Serbia, led by Slobodan Miloshevic, imposed its own rules and control over the presidential and parliamentary elections in order to discredit the democratic values. As a result, the authoritarian political system was thriven to serve the interests of the former ruling nomenclature rather than represent the majority of Serbia’s citizens.[23]

However, the final decision by the opposition political parties’ leaders to take active participation in the elections practically gave both legal and moral verification of the whole political system. The results of elections are not unexpected taking into consideration the starting positions of all participants and the political atmosphere within the whole ex-Yugoslavia at the moment. In the other words, elections in Serbia (and Montenegro) came into agenda after all Yugoslav republics already elected their nationalistic leaderships and it is no secret to say that elections of Slobodan Miloshevic and his SPS party in December 1990 were at a great extent an answer to Tudjman’s and his HDZ victory in Croatia in May of the same year.

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

Prof. Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović

www.global-politics.eu/sotirovic

sotirovic@global-politics.eu

© Vladislav B. Sotirović 2020

[1] Juan Linz, Alfred Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation – Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, p. 38.

[2] For more details about “pater familias” model and its political structure in Balkans see in [Владимир Дворниковић, Карактерологија Југословена, Београд: Просвета, 2000 (reprint from 1939)].

[3] More about personal-party relationships and economic success in Serbia in the early 1990s see in [Tim Judah, The Serbs. History, Myth & Destruction of Yugoslavia, New Haven-London: Yale University Press, 1997, pp. 259–278].

[4] For more details see in [Sabrina P. Ramet, Social Currents in Eastern Europe – The Sources and Meaning of the Great Transformation, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991].

[5] Ernest Gellner, Nations et nationalisme, Paris: Editions Payot, 1989, p. 13.

[6] Vladislav B. Sotirović, “Emigration, Refugees and Ethnic Cleansing in Yugoslavia 1991–2001 in the Context of Transforming Ethnographical Borders into National-State Borders” in Dalia Kuizinienė (ed.), Beginnings and Ends of Emigration. Life Without Borders in the Contemporary World, Kaunas: Versus Aureus, 2005, pp. 94–95.

[7] Robert Thomas, The Politics of Serbia in the 1990s, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 7.

[8] The homogenization of Serbian opinion by Slobodan Miloshevic has begun on April 24th, 1987 when he as the Chairman of the League of Communists of Serbia visited Kosovo Serbs at Kosovo Polje (at the outskirts of Prishtina) – a mythical place for the Serbs where they lost state-national independence to the Ottomans on June 28th, 1389 [Радован Самарџић, Сима М. Ћирковић, Олга Зиројевић, Радмила Тричковић, Душан Т. Батаковић, Веселин Ђуретић, Коста Чавошки, Атанасије Јевтић, Косово и Метохија у српској историји, Београд: Српска књижевна задруга, 1989, pp. 39–40]. After listening grievances of the rallied local Serbs upon long-time discrimination and torture by ethnic Albanians he was the first Serbian official after 1945 to promise them the state’s protection, respect of their human and national rights and equal status within the multiethnic province of Kosovo. His speech at Kosovo Polje was used by TV Belgrade to start creating his charismatic personal cult which had to be proven by mass meetings (“happenings of the people”) in biggest Serbia’s towns from 1987 to 1989 culminating with one million gathered Serbs at a pan-national meeting on 600 anniversary of the Kosovo battle on June 28th, 1989 at Gazimestan. Both Serbian Orthodox Church and Milošević expressed readiness to fight, according to Miloshevic, for protection of human rights as it was done 600 years earlier when on Kosovo Polje Serbian Prince Lazar was defending Christian Europe from Muslim infidels [Slobodan Milošević, „Kosovo i sloga“, NIN, Beograd, 1989-07-02].

[9] Jelena Guskova, Istorija jugoslovenske krize, I, Beograd: IGA“M“, 2003, p. 124.

[10] For more information, see [Vladislav B. Sotirović, Lingvistički model definisanja srpske nacije Vuka Stefanovića Karadžića i projekat Ilije Garašanina o stvaranju lingvistički određene države Srba, Vilnjus: Štamparija Univerziteta u Vilnjusu, 2006].

[11] Tanjug, 1990-09-12.

[12] Milan Andrejević, Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty Research Report, 1990-10-19.

[13] Dragan Bujošević, East European Reporter, autumn/winter 1990.

[14] Od izbornih rituala do slobodnih izbora, Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka, 1991, p. 284; Robert Thomas, The Politics of Serbia in the 1990s, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 74.

[15] Eric D. Gordy, The Culture and Power in Serbia. Nationalism and the Destruction of Alternatives, The Pennsylvania State University, 1999, pp. 8–9.

[16] The constitution was adopted by the national referendum held on July 1–2nd, 1990 under the strong ruling party propaganda in favor of “national interests” and “united Serbia” tasks which had to be defended by the new constitution. Whoever was in opposition to the proposed constitution was labeled as a “national traitor” by Miloshevic’s controlled state’s informative service. However, the people believed that referendum upon a new constitution was in fact plebiscite about Kosovo – to whom this province belonged: to Serbs or Albanians [Kosta Čavoški, „Lex Milošević“, in Ustav kao jemstvo slobode, Beograd: Filip Višnjić, 1995, p. 134]. In fact, the voters put aside the danger for democracy of a constitution drawn up by the one-party assembly and the SPS government gained 97% approval for its right to formulate the constitution prior to elections, ignoring the call by democratic opposition to boycott the referendum. The result of the referendum demonstrated the continuing ability of SPS to control the process of transition in the form of “transition without transition”. See [V. Stevanović, „Demonsko ogledalo vlasti“, Borba, Beograd, November 24–25th, 1990, p. 5]. About the transition and nationalism in East Europe, see [Ruth Petrie (ed.), The Fall of Communism and the Rise of Nationalism, London–Washington: Cassell, 1997].

[17] The first great success of a strong presidential position within the political system in Serbia has been visible by the December 1990’s presidential election results.

[18] About the radical nationalism in Serbia in the 1990s see [Lenard J. Cohen, The Politics of Despair: Radical Nationalism and Regime Crisis in Serbia, Working Paper No. 1, The Kokkalis Program on Southeastern and East-Central Europe, 1999]. About the ideology of Serbian nationalism see [Др Војислав Шешељ, Идеологија српског национализма, Београд: Српска радикална странка, 2003].

[19] Od izbornih rituala do slobodnih izbora, Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka, 1991, p. 278.

[20] Robert Thomas, The Politics of Serbia in the 1990s, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 74.

[21] The Chetniks have been Serbian nationalistic guerilla fighters established in 1904. During the WWII they fought against the Germans, Communists and armed forces of Independent State of Croatia taking acts of revenge against Croatian and Bosnian Muslim civilians for their atrocities against the Serbs within the territory of Independent State of Croatia (which included Croatia, parts of Serbia and the whole portion of Bosnia and Herzegovina). Yugoslav Titoist historiography presented the Chetniks deliberately wrongly as the pro-Fascist collaborators in order to discredit them in the eyes of the common people as they have been the main political opponents to J. B. Tito’s partisans for taking political power in Yugoslavia after the war. See more in [Branko Petranović, Istorija Jugoslavije, II, Beograd: NOLIT, 1988; Коста Николић, Историја равногорског покрета, I–III, Српска Реч: Београд, 1999; Милослав Самарџић, Борбе четника против Немаца и усташа 1941−1945., Први том, Крагујевац: Погледи, 2006].

[22] About this period of the Yugoslav history, see in [Алекс Н. Драгнић, Титова обећана земља Југославија, Београд: Задужбина Студеница−Чигоја штампа, 2004].

[23] The general result of democratic elections in all the six Yugoslav republics in 1990 was that republics’ political elites got democratic legitimacy [Чедомир Антић, Српска историја, четврто издање, Београд: Vukotić media, 2019, 290]. About the post-Communist democratization process in Serbia, see in [John S. Dryzek, Leslie Templeman Holmes, Post-Communist Democratization: Political Discourses Across Thirteen Countries, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp. 57−76].

FOLLOW US ON OUR SOCIAL PLATFORMS